The Minister and the Hell-Raiser: The Origins of the Modern Statehood Movement

Statehood for the District has picked up political momentum in the past several years. H.R. 51, the bill that would create the new Douglass Commonwealth, has a record number of cosponsors in the current Congress, and statehood was a talking point of several major presidential campaigns in 2020. But, the current statehood movement is not a flash in the pan of partisan politics; rather, it is the culmination of a decades-long history of race and democracy.

Allowing the citizens of the District the right to vote for elected representatives and a system of self-government has been a subject of debate since the capital city was first formed. The first constitutional amendment proposing District congressional representation was introduced in 1888. The first Senate hearing on the subject was held in 1916.[1]

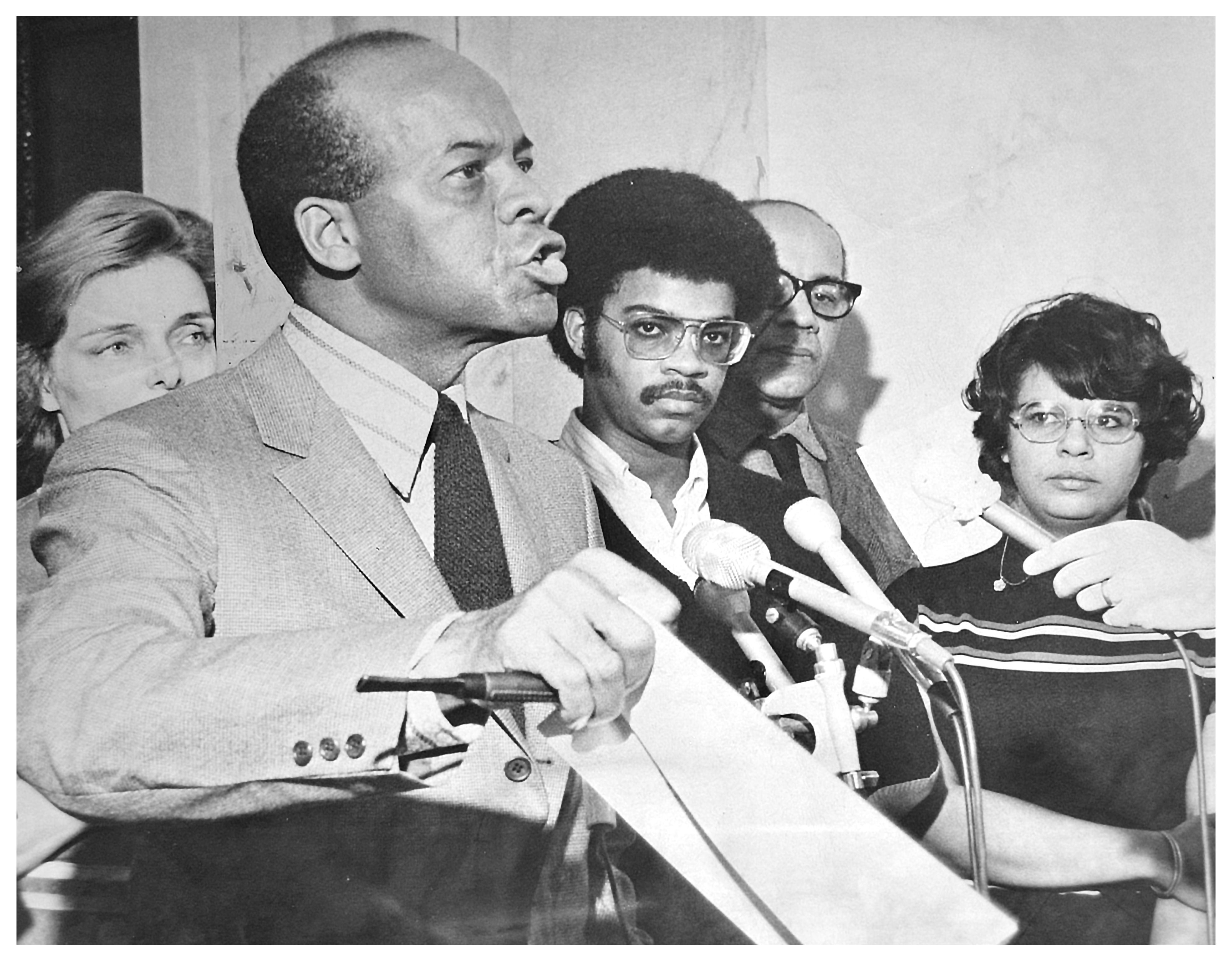

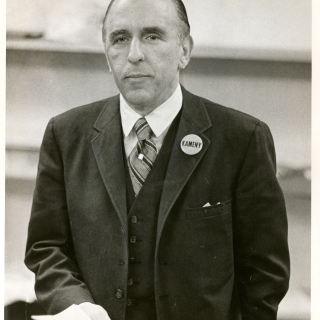

The modern movement for statehood has its roots in the early 1970s in a race between two dynamic and powerful figures in the District’s history: Julius Hobson Sr. and Walter Fauntroy. The two men, both eminent Black civil rights activists, and a handful of other candidates competed in the first election for the District’s newly-created, non-voting delegate seat in 1971. Among the other candidates in this already momentous race was Frank Kameny, an LGBT rights activist and the first openly gay man to run for Congress.

In the early 60s, Hobson and Fauntroy were the leaders of the District chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality [CORE] and Martin Luther King Jr’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference [SCLC], respectively. The two had worked closely together on a committee to coordinate the national March on Washington, but their brief partnership and shared cause were where the similarities ended.

Fauntroy was a District-native, minister, and graduate of Dunbar High School. He followed closely in the nonviolent footsteps of King, his friend and mentor. Coretta Scott King, Rev. King’s widow, campaigned for Fauntroy several times. As characterized by his supporters in a candidate profile, “it is [Fauntroy’s] rapport with the man in the street, particularly in the city’s Black neighborhoods, that is the source of his political strength."[2]

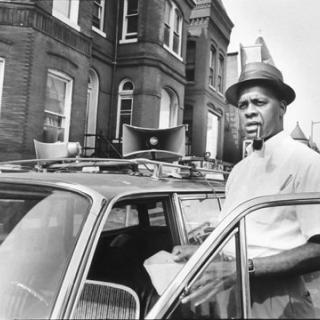

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Hobson was a firebrand and “master of invective,”[3] known for his theatrical stunts calling attention to the inequalities of the city. As opposed to the devout Fauntroy, Hobson was an atheist who believed that “there is no God to make things better in the end; there is only the here and now."[4]

Hobson devoted a large part of his activism to ensuring equality in the District’s schools. More than a decade after national desegregation, he successfully sued the District school system for continuing to discriminate against Black students. A year later, in 1968, Hobson ran for the school board and swept six of the city’s eight wards.[4]

To Take Hold of Its Future

The position of non-voting delegate was re-established on September 22, 1970, signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The delegate seat was first established a century prior during Reconstruction and only lasted four years before being abolished in 1875. Republican Norton Chipman held the seat for its entire two-term existence, beating out Frederick Douglass for the Republican Party nomination in 1871.[5]

Re-establishing the seat was part of a larger plan by Nixon to give the District more self-representation and self-rule. He outlined his plan in a special message to Congress in 1969:

At issue is whether the city will be enabled to take hold of its future: whether its institutions will be reformed so that its government can truly represent its citizens and act upon their needs. Good government, in the case of a city, must be local government.[6]

Nixon proposed a commission to explore self-government options and a constitutional amendment to allow the District at least one full House member and “the possibility of two Senators.”[6] He viewed the non-voting delegate seat as a temporary solution to be put in place while a constitutional amendment was worked out.

Fauntroy won handily against six other candidates in the Democratic primary on January 12, 1971. “While I am pleased at this victory, I am mindful that this election was not only for a candidate, but also for a cause--the cause of self-government; the cause of self-rule,” Fauntroy said in his victory statement.[7] Fauntroy advocated for a bill instituting self-rule and a subsequent constitutional amendment implementing elected representation for the District, similar to Nixon’s proposal.

While Fauntroy focused on a more limited approach of self-rule, Hobson made outright statehood his “bread and butter issue, using it as the starting point for most of his presentations.”[8] He was singularly focused on the issue, even calling a press conference to blast the local media for not covering his keystone policy enough.[9]

Hobson launched his campaign in front of a crowd of 500 supporters on February 18 under the banner of the newly formed Statehood Party.[10] The party was created based on an idea by journalist Sam Smith, the editor of the alternative newspaper the D.C. Gazette.

Statehood: Nothing More, Nor Less

Smith argued in a 1970 article, titled “The Case for DC Statehood,” that the goal of statehood could be accomplished through an act of Congress, requiring only a simple majority as opposed to the two-thirds vote required by a constitutional amendment. The act would shrink the boundaries of the federal district to just an area around the White House, National Mall, and Capitol Hill. The rest of the area would be admitted into the Union as a state on an “equal footing” with the other 50 states.[11]

“In the old days, when Congress admitted new states, it put it even more gracefully and accurately. The states were declared a ‘new and entire member of the United States of America,’” Smith wrote. “The District has never been an entire member of the United States of America. It is the indentured servant of the nation. Our goal must be simple and clear: the US must let us in."[11]

In his campaign, Hobson echoed many of the ideas expressed by Smith, and he defended against attacks from his critics who believed in a more realistic approach of home rule with three arguments.

First, Hobson argued that statehood would be a more expedient process of ensuring representation because it would only require a simple majority vote in Congress, as opposed to the two-thirds majority needed for a constitutional amendment.[8]

Second, similar to his expedience claim, he asserted that it would be easier to win over support for statehood because the proposal was simpler for everyday Americans to comprehend.[8] Americans outside of the District generally understood the process and meaning of statehood; many even witnessed Hawaii and Alaska achieve statehood two decades earlier. In contrast, home rule was a more novel idea with various competing proposals.

Smith wrote on this point in 1970:

Statehood means nothing more nor less than what Wyoming, Rhode Island, Delaware, or any of the states smaller and larger than the District enjoy. When Alaska became a state, Congress declared that it was “admitted into the Union on an equal footing with the other States in all respects whatever.” That’s what we should demand: equal footing, not some more benevolent form of colonialism foisted off as “home rule.”[11]

Lastly, Hobson appealed to the history of the District, alluding to the previous forms of self-government that have been stripped from the District and arguing that statehood would be a permanent solution for the District. “We are pushing for a process that cannot be taken away, once we get it,” Hobson said. “Once we become a state, Congress would have to violate the hell out of the Constitution to take that away from us.”[3]

Raise Hell on Behalf of the District

Hobson’s brash rhetoric often overshadowed his policy proposals in the local press, and to an extent, Hobson embraced this and made it a point to draw attention to his unconventional politics. He believed it was not the job of the delegate to be polite.

“Since the role of the delegate is unique, my approach will be unique,” Hobson told the Washington Afro-American. “I will not get into the seniority line. I will not play games with Broyhill, Natcher, McMillan, and others of that ilk. I will use the office and its resources to get statehood for the District.”[12]

“When he ran for non-voting delegate in 1971, he did so for the express purpose of being permitted to raise hell on behalf of the District in the United States Congress,” Smith reflected on his friend’s campaign years later.[13]

Fauntroy criticized his opponent for his bold rhetoric and methods. “The fact is that Hobson has not been very effective as a public official. After a year on the school board, the voters turned him out. If the same Hobson is elected, it will not be too longer that we will have the non-voting delegate,” Fauntroy told the Afro-American.[14]

Fauntroy, on the other hand, believed in the power of consensus building and organizing. He campaigned on the promise to organize people to vote out anti-District congressmembers, a strategy he successfully used against Representative John McMillan from South Carolina several years later.[15]

Fauntroy’s superior organizing abilities paid off. On election day, on March 23, 1971, the minister won the election with almost 60% of the vote, giving him a strong mandate to advocate for the District in Congress.[16]

Hobson finished in a distant third, with 13.4% of the vote, behind Republican John Nevius, who garnered 25%. In his concession speech, Hobson praised the other candidates in the race, but he did not congratulate his opponent. Rather, he reserved some pointed remarks for the Democratic Party and its candidate.[16]

“I hope Washington will not become a rotten, borough city and be controlled by a political machine like Chicago,” Hobson said. “I ran on principle, and my principle about the Democratic candidate is the same as it was yesterday.”[16]

Fauntroy was sworn in as the first District delegate in nearly a century on April 19, 1971.[17] He pressed forward on a home rule bill, passing the historic legislation in 1973. Hobson continued his fight for statehood from within the District, successfully running for an at-large seat on the new city council, but he passed away soon after in 1977 at the age of 54 after a long fight with cancer.[4]

Fauntroy sustained his critique of the plan for Statehood. His biggest objection to the proposal was that it would strip the District of crucial federal funding. Fauntroy also compared statehood to “doing to the citizens of the District of Columbia what the federal government did to the Indians.”[18]

“[Statehood would] give us a reservation after they kill all of the buffalo and rob the land of its potential,” he said later in 1971.[18]

Slowly, over the next two decades, Fauntroy came to embrace Hobson’s proposal. In 1982, he spoke of statehood as a “new chapter in our continuing struggle for self-determination.”[19] Fauntroy introduced the first bill to create the state of New Columbia in the House in 1984.

He and Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy, a champion of the District statehood movement, reintroduced the New Columbia Admission Act in the House and Senate in each session of Congress until Fauntroy retired in 1990.[20] His successor, Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton picked up the mantle of the congressional struggle for statehood.

Footnotes

- ^ “District of Columbia, Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments.” July 19, 1973 https://books.google.com/books?id=uNCl3t4-BrkC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=nixo…

- ^ Barnes, Bart. "Fauntroy's Strength: Attracting People: The Candidates." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Mar 10, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper….

- a, b Barnes, Bart. "Hobson: A Master of Invective, Issues: The Candidates." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Mar 12, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper….

- a, b, c Gorney, Cynthia. “Julius Hobson Sr. Dies” Washington Post. March 24, 1977. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1977/03/24/julius-hobso…

- ^ Gibbs, C.R. “The District Had a Voice, if Not a Vote, in the 42nd Congress” Washington Post. March 2, 1989. https://search-proquest-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/docview/140076816/3B90FC0F…

- a, b Nixon, Richard. “Special Message to the Congress on the District of Columbia” The American Presidency Project, University of California Santa Barbara. April 28, 1969. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-…

- ^ Bernstein, Carl and Whitaker, Joseph D. “Fauntroy ties election win to home rule: Fauntory ties win to home rule.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973) Jan. 14, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper…

- a, b, c Boldt, David R. 1971. "District Home Rule, Not Crime, is Main Issue in Campaign: Campaign Focuses on D. C. Home Rule, Not Crime." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Mar 19, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper….

- ^ Boldt, David R. and Whitaker, Joseph D. "Hobson Says Press Ignores Statehood: Simpler Course." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Mar 06, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper….

- ^ Boldt, David R. "Delegate Candidate Hobson Vows at Kickoff to Campaign on Issues." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Feb 18, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper….

- a, b, c Smith, Sam. “The Case for DC Statehood” D.C. Gazette. May 3, 1970. https://samsmitharchives.wordpress.com/1970/05/03/dc-statehood-the-firs…

- ^ Elam, Joe. “Candidates optimistic over role of district non-voting delegate.” Washington Afro-American. March 23, 1971. https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=BeIT3YV5QzEC&dat=19710323…

- ^ Smith, Sam. “Place.” Sam Smith’s Memoirs. November 10, 2006. https://samsmitharchives.wordpress.com/2006/11/10/bush-lost-but-we-have…

- ^ Elam, Joe. “It’s election day; candidates hustle.” Washington Afro-American. March 23, 1971. https://news.google.com/newspapers/p/afro?nid=BeIT3YV5QzEC&dat=19710323…

- ^ Asch, Chris Myers, and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation's Capital [Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2017] p. 379

- a, b, c Boldt, David R. "Fauntroy Sweeps Delegate Race: Wins in 7 of City's 8 Wards." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Mar 24, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper…

- ^ Boldt, David R. "Delegate Fauntroy: First in a Century: Fauntroy Takes Seat as Delegate to Congress." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Apr 20, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper…

- a, b "Fauntroy Attacks Plan on Statehood." The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), Jul 15, 1971. https://search-proquest-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspaper….

- ^ Musgrove, George Derek. ““Statehood is Far More Difficult”: The Struggle for D.C. Self-Determination, 1980–2017” Washington History. Vol. 29, No. 2 (Fall 2017), pp. 3-17 (15 pages)

- ^ https://www.congress.gov/search?q={%22congress%22:%22all%22,%22source%22:%22all%22,%22search%22:%22\%22new+columbia+admission+act\%22%22}&searchResultViewType=expanded&s=4

![Fauntroy [at mic] and Hobson [center] at news conference for March on Washington Walter Fauntroy speaks at March on Washington planning news conference in 1963, with Hobson standing behind him.](/sites/default/files/styles/embed_full_width/public/Hobson%20and%20Fauntroy%201963.jpg?itok=lhk9i5z8)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)