In the 1870s, D.C. Briefly Had a Delegate in Congress

A century before Walter Fauntroy and Julius Hobson competed for the modern District Delegate seat, initiating a decades-long debate over full District representation in Congress, another man held the same office. His election, his brief tenure in office, and the ultimate elimination of his seat make up a lesser known part of the history of race and democracy in the nation’s capital.

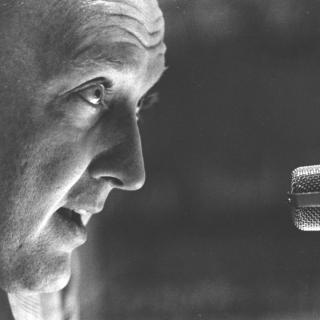

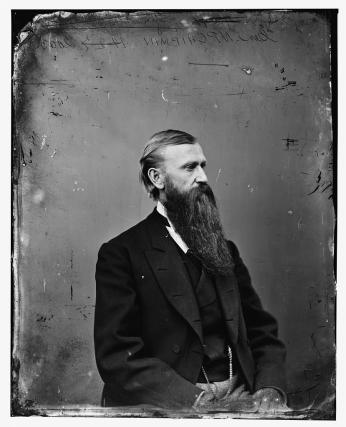

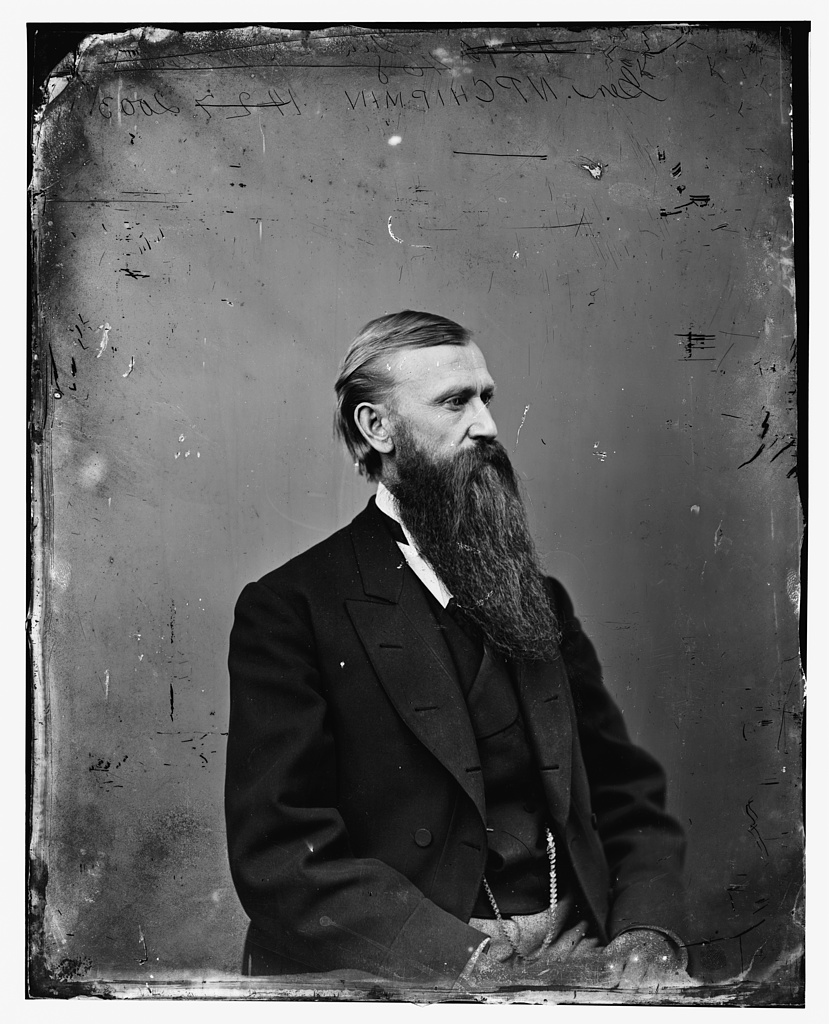

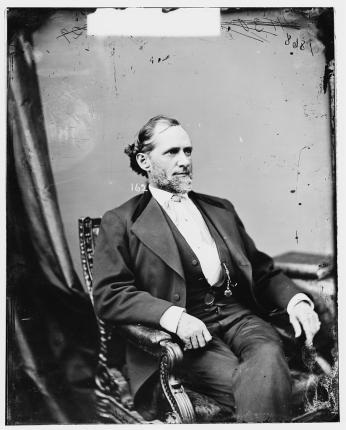

Norton Parker Chipman, an Ohio-born Republican, was a Union brigadier general in the Civil war. Before the war, he got his start as a lawyer in a different Washington, that of Washington, Iowa. Chipman served under General Ulysses S. Grant and became close friends with the future president. After the war, Chipman gained prominence as a successful lawyer in the Andersonville Confederate war camp case, prosecuting the Confederate prison commandant for war crimes.[1]

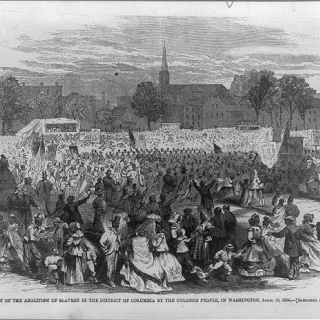

In 1871, as the electoral reforms of the Reconstruction Era were sweeping the nation, Congress passed another important bill: the Organic Act of 1871. Like its homonymous predecessor, the Organic Act of 1801, the 1871 bill redefined the face of the District. Instead of being broken up into the three municipalities of Georgetown, the City of Washington, and Washington County, the District would be consolidated under just the title of the District of Columbia, as we know it to be today.[2]

Even more notably, the bill established a new municipal government with an appointed executive, an elected legislature to govern this unified District, and the first non-voting District delegate seat in Congress. President Grant signed the bill into law in February 1871 and appointed his friend Chipman to be the District Secretary, the second-in-command official of the city. Chipman wouldn’t hold this office for very long, though.

A Political Love Feast

Shortly after the District government was established, several hundred Republican men gathered in downtown DC for a party convention, which the Evening Star at the time deemed a “political love feast.” Chipman was invited to address this conference of glad-handing elites. “He urged that as the influence of the voters of the District is felt throughout the country, it was [the Republicans’] duty to remain united,” the Evening Star reported of his speech.[3]

Later in the month, Republican delegates reconvened to nominate a Republican candidate for the upcoming District Delegate election and to establish the party’s platform. Both this meeting and the one earlier in the month were comprised of a biracial group of delegates, emblematic of the growing electoral power of newly enfranchised Black Americans.

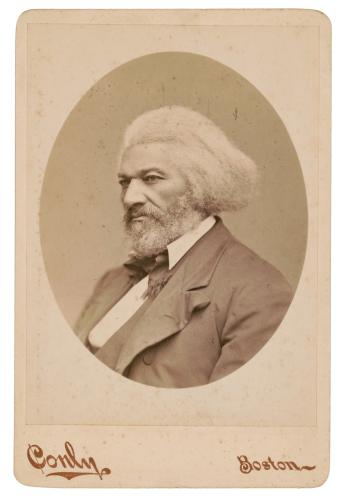

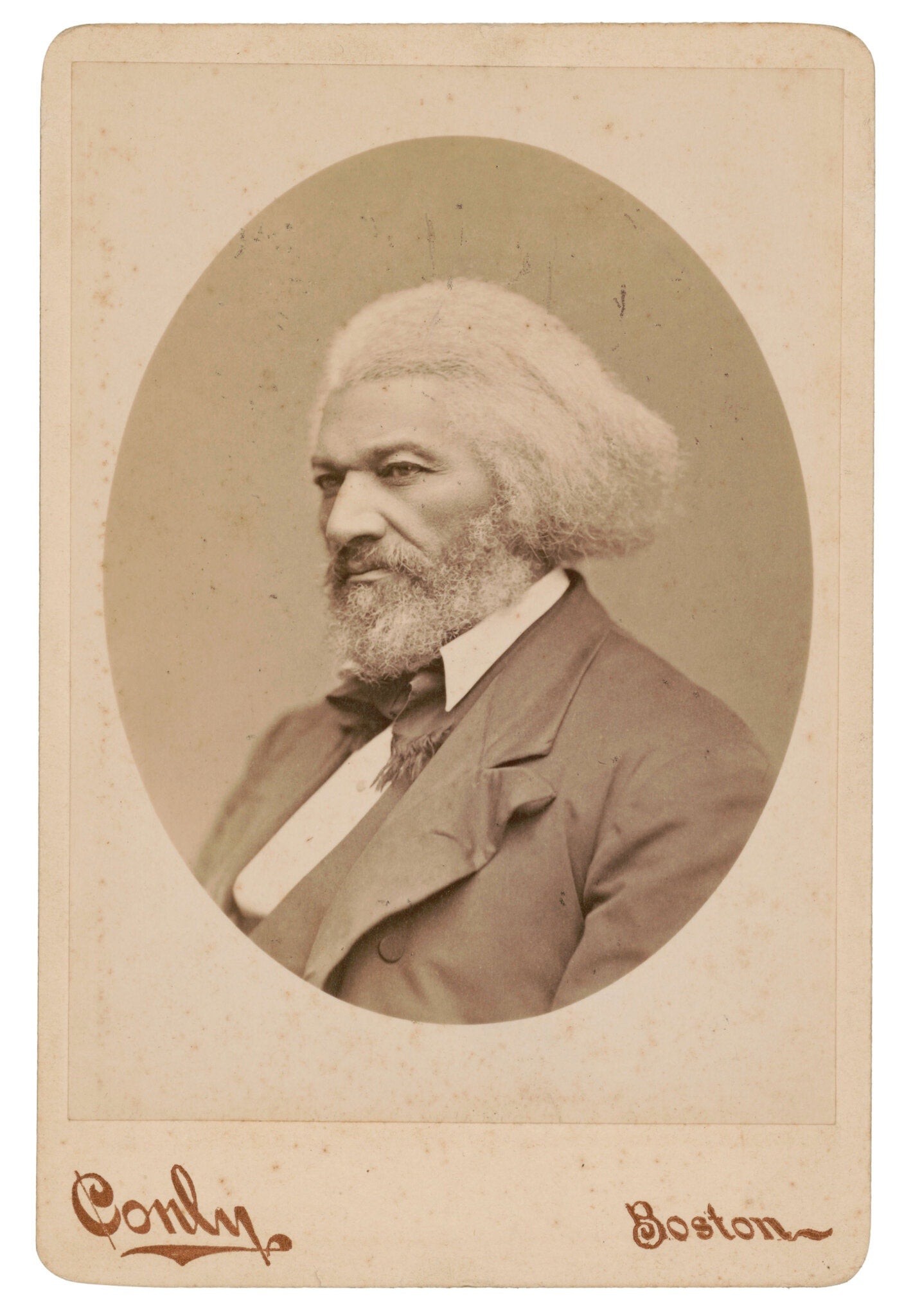

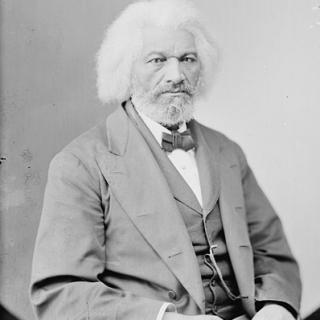

Black civil rights leader Frederick Douglass presided over this meeting, and he and Chipman were the two leading contenders for the delegate nomination. Chipman received 44 votes on the first ballot to Douglass’ twenty-seven, and on the second ballot the next day, the delegates rallied behind Chipman, giving him the nomination.

“While I am in favor of no distinctions on the account of color, remembering the stripes, remembering the 250 years of bondage in this land...in view of that history...I say, whenever the black man and the white man, equally eligible, equally available, equally qualified for an office, present themselves for that office, the black man, at this juncture of our affairs, should be preferred,” Douglass said in a concession speech.[4]

Nevertheless, Douglass threw his support behind Chipman’s candidacy. “I stand here and affirm that whatever any other man will do to make the candidate which you have now honored with this nomination victorious at the polls, I am ready to do,” Douglass pledged. “Of course I would have felt a little better if it had been me, for I am human,” Douglass joked, eliciting laughter from the audience.[4]

In his address accepting the nomination, Chipman excoriated the Democratic Party for their exclusionary, racist actions and platform. “The contrast between this convention and the one which recently assembled for the purpose of nominating a democratic candidate...is marked in a way not to be mistaken,” said Chipman. “That convention excluded...by the essence of its constitution, at least one-quarter of the entire population of this District.”[4]

“Is that democracy which deliberately erects an impassable barrier against a large and respectable class of our citizens, whose only offence is the color of their complexion? No! It is oligarchy!” Chipman proclaimed to cheers of “That’s so!” from the audience.[4]

The “Good Old Times”

Norton faced off against Democrat Richard T. Merrick, the son of a former Maryland Senator. Merrick continually attempted to make the question of integrating the city’s public schools the primary focus of the campaign. “Mr. Merrick was disgusted at the idea of mixed schools, and he believed the practical application of the system would be to ruin the public schools,” the Evening Star reported.[5]

Chipman avoided taking a stance on the issue, arguing that the delegate should focus on securing “the material interest of the District.” Chipman believed the decision on school segregation should be left to the voters.[6]

“You may express whatever opinion you choose upon the subject, but we are not bound to join issue with you. I leave the whole subject to the people and am willing to trust them. You seem not willing to do either,” Chipman wrote to Merrick in an open letter on the subject.[6] The matter of school integration would not be settled for another 80 years.

District residents cast their first ever ballots for a Congressional delegate on April 20th, 1871, a century, almost to the day, before Walter Fauntroy was seated as the next delegate on April 19th, 1971. Fulfilling his pledge to support Chipman, Frederick Douglass penned a letter to the “colored men of Columbia” in his newspaper, The New National Era, urging them to vote for the Republican candidate.[7]

He wrote in scathing, unequivocal terms:

Hell and heaven are not more opposite than are the spirit and purposes of these two parties...Mr. Merrick stands for the past. He clings to the “good old times”--the times [of] slave holding, slave selling, slave hunting...when a colored man could not in safety visit the capital of the country...Yes. Richard T. Merrick represents these “good old times,” and his election would be a triumph, a resurrection of the spirit of these “good old times.”

On the other hand, General N. P. Chipman represents the new era of American civilization, which gives all men an equal chance in the race of life, which leaves no man in bondage...For one, I say shame, eternal shame, upon any colored voter who supports Richard T. Merrick, and withered be the black man’s arm and blasted be the black man’s hand who casts a vote against General N. P. Chipman.[7]

With the support of “the entire colored vote,” Chipman defeated Merrick by a margin of 15,195 to 11,104 votes.[8]

Undistinguished Service

In a 1988 profile of Chipman, The Washington Post reflected that his “congressional service was undistinguished.” Albeit, he was hampered by not being able to vote on the House floor and only being able to serve two terms before his seat vanished.

Chipman may not have had a vote in Congress, but he had a voice. He was allowed to give speeches on the House floor, and he made full use of this limited power. His thoroughly researched and well delivered speeches were “the hallmark of his tenure” in office.[9] Chipman used his speeches to call on Congress to take on fiscal responsibility of the underdeveloped city. In one ultimately unsuccessful proposal, he suggested Congress sell 2.5 million square acres of land to fund the city’s public schools.

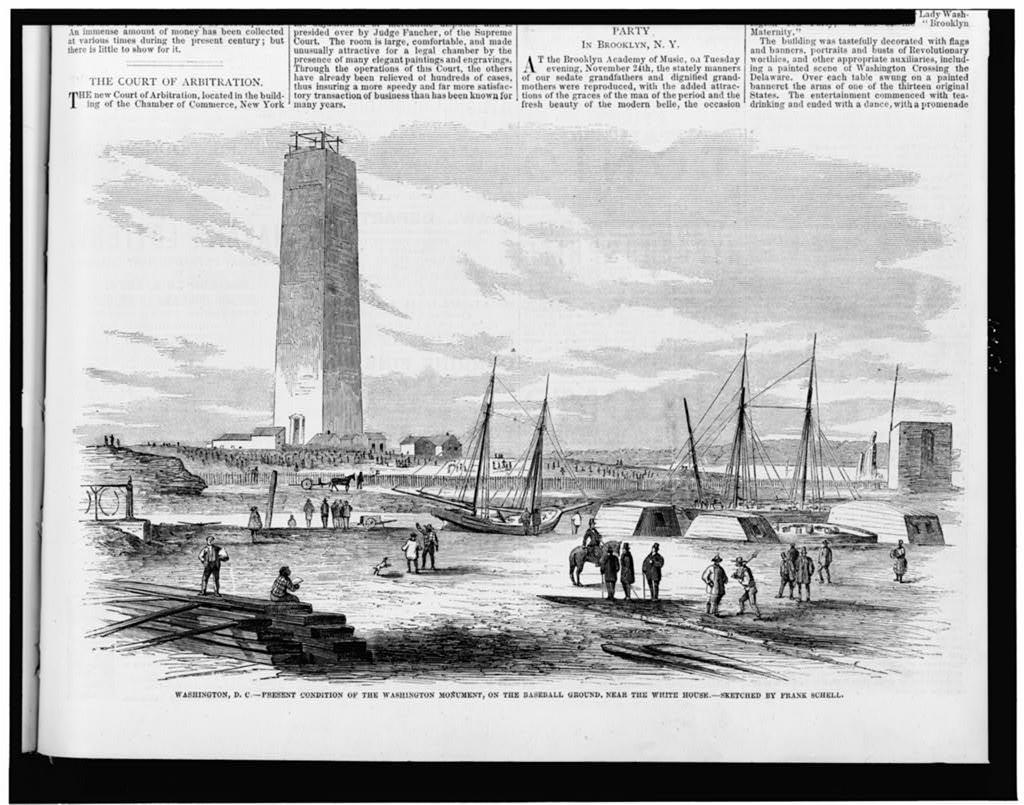

Chipman also dedicated a significant portion of his second term to advocating for the completion of the Washington Monument, which stood unfinished for years as an eyesore of the developing Washington skyline. He was appointed chairman of a House Select Committee to oversee the creation of a report on the economic and engineering feasibility of continuing the monument.[9]

In a long speech on the House floor presenting his report, Chipman gave a comprehensive chronology of the decades of struggling to fund and complete the monument commemorating the nation’s founding father. To save on costs, Chipman’s report called for abandoning part of the original plan for the monument that would have built a “pantheon” around the base of the obelisk.

He discussed this change in design in his speech, defending the more modest design, “There is something in this simple, majestic obelisk to my mind eminently proper as commemorative of the character of Washington...There is something in this obelisk without ornament, pure and simple in its design, not unlike the character of Washington.”[10]

Chipman had an ambitious goal of finishing the monument by the nation’s centennial birthday, about two years later. He believed that accomplishing this deadline was imperative to demonstrating to the world that America is a respectable nation and able to execute its loftiest goals.

Concluding his speech, he said, “Complete it [before] your centennial day arrives, or let no American citizen look toward heaven on that glad morn and thank God that this is a land of liberty and that we are a free people. Complete it, or look not back to a noble ancestry; but confess that your nation is in its decadence, and that its days are already numbered.”[10]

The monument was not finished by the centennial, taking another decade to finally wrap up. Chipman may not have achieved his goal of pushing Congress to act expediently, but in his work for the Select Committee and his ensuing speech, Chipman directly shaped the skyline of DC, cementing the plan for the obelisk as it is today.

Democracy Revoked

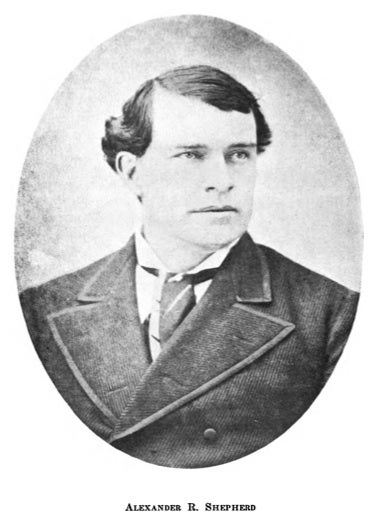

While Chipman gave speeches on Capitol Hill, elsewhere in the District, the new local government was busy at work. Alexander “Boss” Shepherd, a local businessman, led the new Board of Public Works, a commission of five appointed members. Shepherd cajoled the other members of the board into supporting his ambitious city planning and infrastructure initiatives.

Shepherd commenced a series of major public works projects, beginning Washington’s transformation from a relative backwater compared to other national capitals of the day to a world-class city. Laborers completed the most drastic infrastructure improvements in the District since its founding, laying down hundreds of miles of roads, sidewalks, and pipes and planting tens of thousands of trees.[11]

In the process, Shepherd ran up the city’s debt, and Congress took notice. A joint committee was formed to investigate the excessive use of funds, allegations of corruptions, and other breeches in public trust.

The committee’s final report chastised Shepherd for his exorbitant spending, and the report placed blame for this malfeasance not only on Shepherd but more largely on the voters of the District, even though the Board of Public Works was entirely unelected. It called on Congress to reform the District government to avoid these excesses. Congress listened and quickly voted to replace the elected municipal government with a panel of three appointed commissioners, with no mechanism of soliciting the voters’ opinion.[11]

Aside from installing the new commission, the move by Congress also abolished Chipman’s seat and he retired from District politics, or what was left of it, after his second term ended in early 1875. He later moved to California to become a judge.

This decision to blame District voters for Shepherd’s spending was intrinsically linked to race. Discourse during Reconstruction often eschewed newly enfranchised Black populations for not understanding how to properly wield their political power. “[Municipal reformers] asserted that black voters were ignorant and easily led, ridiculed African Americans’ political meetings, and ignored or maligned black leaders who disagreed with them,” wrote historian Kate Masur.[11]

“We cannot know whether Congress would have ended self-government in the District if its laboring population had been largely of European descent, but there can be no doubt that it was easier to justify denying self-government to masses of black Washingtonians than it would have been if the voters in question had been of European or even Catholic origin,” wrote Masur.[11]

Footnotes

- ^ Gibbs, C.R. “The District Had a Voice, if Not a Vote, in the 42nd Congress” Washington Post. March 2, 1989. https://search-proquest-com.proxygw.wrlc.org/docview/140076816/3B90FC0F…

- ^ Organic Act of 1871: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/41st-congress/session-3/…

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 08 March 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1871-03-08/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b, c, d Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 30 March 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1871-03-30/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 29 March 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1871-03-29/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b New national era. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 13 April 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026753/1871-04-13/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b New national era. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 20 April 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026753/1871-04-20/ed-1/seq-…;

- ^ Alexandria gazette. [volume] (Alexandria, D.C.), 21 April 1871. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85025007/1871-04-21/ed-1/seq-…;

- a, b Hogg, Jeffrey Norton Parker Chipman: A Biography of the Andersonville War Crimes Prosecutor. [North Carolina: McFarland, 2008]

- a, b “Washington National Monument : shall the unfinished obelisk stand a monument of national disgrace and national dishonor? : speeches of Hon. Norton P. Chipman of the District of Columbia, Hon. R.C. McCormick of Arizona, Hon. Jasper D. Ward of Illinois, Hon. John B. Storm of Pennsylvania, Hon. J.B. Sener of Virginia, Hon. S.S. Cox of New York, in the House of Representatives,” June 4, 1874. Washington : G.P.O., 1874. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t9474n05q

- a, b, c, d Masur, Kate. An Example for All the Land : Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, DC. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010) p. 214-256

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)