Brood X in the Eighteenth-Century Headlines

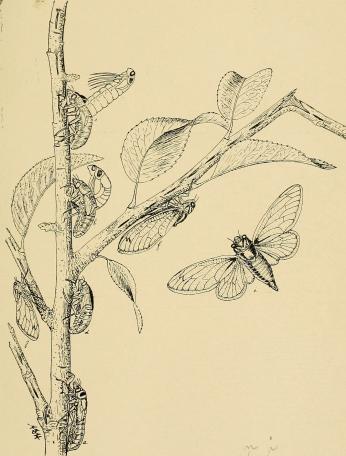

Every seventeen years, Brood X gets a lot of press in the D.C. area. Washingtonians are fascinated by (and maybe even scared of) this incredible natural phenomenon: red-eyed insects emerging from the ground in the billions, shedding their skins and buzzing in the trees. Locals have their own stories and memories of previous “cicada years,” and the cyclical appearances are an interesting way to mark the passage of time.

As a historian—and an area native who remembers playing with Brood X cicadas as a child—seeing the media “buzz” makes me wonder how our ancestors reacted to the periodical swarms. Who were the first people to realize what was going on? Did they understand the seventeen-year cycle? Were they afraid, curious, or unbothered? Cicadas have been appearing for thousands of years, at least, so humans must have had something to say about them.

As I suspected, Washington-area locals have been fascinated by Brood X for a very long time. Though indigenous peoples observed them long before Europeans reached American shores, the earliest written accounts of periodical cicadas come to us from the letters and diaries of colonists in the eighteenth century. Unfamiliar with the species, it seems that they viewed the insects as a bad omen, linked to outbreaks of disease or war.[1] One man in Virginia, writing in 1705, described a year when several strange natural occurrences frightened colonists, including “swarms of flies about an inch long and big as the tip of a man’s little finger, rising out of spigot holes in the earth.”[2] There has always been fear, apparently, even if we no longer equate Brood X to a Biblical plague of locusts.

In Philadelphia, another city inhabited by Brood X, a Swedish reverend gives us a much more detailed account of Americans’ reactions to the cicadas. On May 9, 1715, Andreas Sandel recorded in his journal that “some singular flies” had emerged from the ground, “the English call them locusts.”[3] Far from being frightened by the insects, Sandel actually calls them “wonderful.”[4] Their holes and shells could be seen everywhere, in the city’s dirt roads and dotting country fields. What Sandel finds most “astonishing,” though, is that people with brave stomachs began to experiment. “When they first appeared,” he reports, “some of the people split them open and [ate] them.”[5] Sandel later writes that the locusts, curiously, disappeared after only a short time. While not written in our area, this account must sound suspiciously familiar to anyone stalking all the latest D.C. headlines—and cicada recipe ideas.

The first scientific study of periodical cicadas came in 1756, originally published in Stockholm. The Swedish naturalist Pehr Kalm happened to visit the American colonies during Brood X’s 1749 appearance. They made quite an impression, since he later noted that he saw “a kind of locusts which about every seventeenth year come hither in incredible numbers.”[6] What he remembers most is the loud noise, “such a noise in the trees…that two persons that meet in such places, can not understand each other, unless they speak louder than the locusts can chirp.”[7] As a mere visitor to America, Kalm was certainly not the first to understand the life cycle and behaviors of the cicadas, but his account of the bizarre insects inspired further study from European scientists throughout the rest of the eighteenth century. In 1788, they gave the American “locusts” a new name and classification: Cicada septendecim.[8]

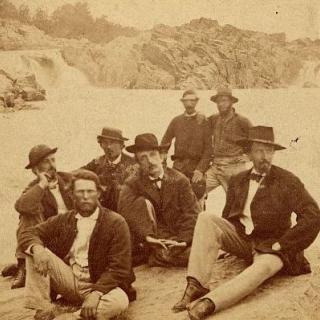

The earliest American scientist to study Brood X was likely Benjamin Banneker, working from his home near Ellicott City, Maryland.[9] The son of free Black parents, Banneker was a self-taught naturalist, astronomer, mathematician, and surveyor. In addition to writing an almanac, he is best known in the D.C. area for helping to survey parts of the future capital city. Banneker was seventeen years old during his first cicada year, in 1749. Local lore must have taught him to be wary, because he writes that he “imagined they came to eat and destroy the fruit of the Earth…I therefore began to kill and destroy them.”[10] Seventeen years later, in 1766, the fear and suspicion gave way to curiosity. Banneker was already pursuing his love of science, making studies of astronomy and the natural world—Brood X was now another subject of study. He correctly noted that seventeen years passed between appearances, the cicadas only emerge for brief periods of time, and that they are relatively harmless to the environment. In 1800, when he was sixty-eight years old, Banneker finally summarized years of careful observation in a journal entry, which predicted—again, correctly—that 1800 would be another cicada year.[11]

In the nineteenth century, Washingtonians continued to explore their fascination with the periodical cicadas. Written accounts of Brood X became more common as printed media became more widespread and accessible—and as scientific interests continued to expand. At the end of the century, in 1898, the Department of Agriculture commissioned its first report on the “distinctly American” phenomenon of “peculiar interest” to the public.[12] The author of the study, C.L. Marlatt, described cicada broods all over the United States (Brood X is one of at least fifteen) and also wrote about their impact on American popular culture. It may be hard for us to imagine, since we only talk about them every seventeen years, but these bugs have left their mark.

But looking at accounts of Brood X from early America has revealed that little changes in the cicada-related news cycle. People were just as fascinated then as they are now—even more so, maybe, since many of the colonists were experiencing a new world with unfamiliar nature. They were afraid, curious, amazed, and repulsed. They wondered how long they would stay, complained about the noise, and discovered a good new source of protein!

Footnotes

- ^ C.L. Marlatt, The Periodical Cicada (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1898), 112.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Extracts from the Journal of Rev. Andreas Sandel, Pastor of ‘Gloria Dei’ Swedish Lutheran Church, Philadelphia, 1702-1719,” in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography XXX (Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1906), 448.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Extracts from the Journal of Rev. Andreas Sandel,” 449.

- ^ Marlatt, 113.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Nora McGreevy, “Meet Benjamin Banneker, the Black Scientist Who Documented Brood X Cicadas in the Late 1700s,” Smithsonian Magazine, May 7, 2021, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/meet-benjamin-banneker-black-…

- ^ Janet E. Barber, “Benjamin Banneker’s Original Handwritten Document: Observations and Study of the Cicada,” in Journal of Humanistic Mathematics 4, Issue 1 (January 2014), 116

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ James Wilson and L.O. Howard, “Letter of Transmittal,” in The Periodical Cicada, 3.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)