Juvenile Justice on Trial: Carrie Weaver Smith and the National Training School for Girls

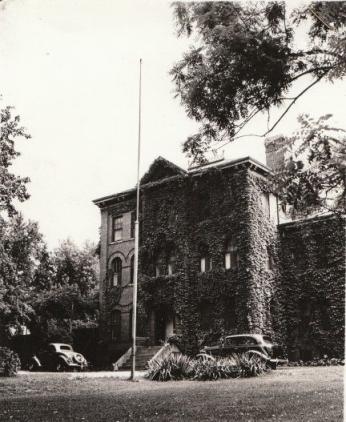

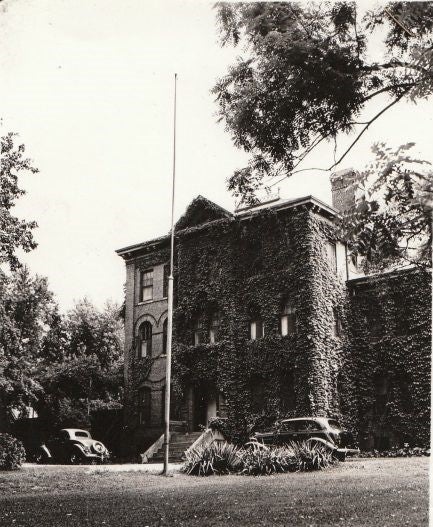

In 1936, Carrie Weaver Smith came to Washington to make a difference. Smith was hired as superintendent of the National Training School for Girls, the District’s reformatory for female delinquents. Standing where Sibley Hospital is now located, the National Training School was a decrepit facility with a reputation for near-medieval cruelty. Smith was determined to change that. Boasting decades of experience and fluency in Progressive ideals of juvenile justice, the 51-year-old social worker planned to turn NTS into a model institution.

Three years later, Carrie Weaver Smith came to the D.C. Board of Commissioners for vindication. Her tenure at the National Training School had lasted 20 months. She enacted her vision of reform, but after an outbreak of violence at the school, the D.C. Board of Public Welfare fired her. The institution swiftly returned to the punitive principles Smith abhorred. But she was not ready to give up.

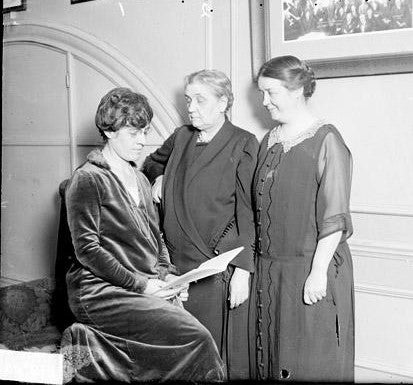

With help from Eleanor Roosevelt, Smith compelled Washington’s government to hold hearings about her time in office. In a month-long trial, Smith, her allies, and her enemies would all have a chance to debate the meaning of juvenile justice. Smith did not want her job back. Instead, she wanted to exonerate her theories of justice and the girls she crusaded to save. Her quest, passionate and futile, revealed the fundamentally racial and sexual boundaries that determined which young Washingtonians could or should be saved in New Deal-era D.C.

Smith’s involvement with the National Training School began when she was hired in February 1936. Smith had spent her career in juvenile justice, including stints leading the State Training School for Girls in Texas and the Montrose School in Maryland,[1] but what she discovered at NTS shocked her. The school buildings were crumbling and lacked consistent heat and running water. The girls incarcerated within them received little education, and were so poorly clothed that they could not go outside during the winter. The daily count of rats killed hovered in the dozens.[2]

To raise awareness, Smith invited politicians to tour the school. They too were stunned. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt came in March, and wrote in her column My Day about how she shuddered at “children walled in like prisoners.” Sen. Royal Copeland told reporters that “Noah’s ark was a vacuum compared to the crowded conditions” at NTS and that he would “send a girl to hell before I’d send her there.”[3] He and other senators demanded reform.

Luckily, Smith had a plan. For the past four decades, “child savers” like her had developed juvenile justice systems nationwide. They saw “the girl problem,” as female delinquency was called, as the product of a corrupt industrial world which caused young women to stray from social and sexual norms. To prevent this, child savers desired aggressive but benevolent state intervention, in the form of reformatories, to control wayward girls.[4] In Texas and Maryland, Smith implemented the movement’s best practices, housing girls in cottages and providing them with quality vocational education and instruction on proper sexual behavior. She intended to continue these practices at NTS, promising to treat its girls with affection and “fit them for a useful existence.”[5]

But the residents of the National Training School differed in one critical way from those Smith had worked with before- they were overwhelmingly Black. In general, White child savers of the early 1900s had ignored Black children and left African Americans leaders to create their own reform schools.[6] Washington was unique in incorporating nonwhite children into its juvenile system, but it was hardly color blind. White girls labeled delinquent could be sent to one of many institutions, but Black girls were only welcome at the “barbaric” National Training School. With few exceptions, the Black residents of NTS also had histories of venereal disease, a trait which marked them dangerous enough to be included in a juvenile system that otherwise ignored nonwhite people like them.[7]

Despite this crucial difference, Smith set about reshaping NTS in the child saving mold. Having shocked congressmen into awareness, she secured $100,000 to remodel the school and build the sort of homey cottage system that had worked in Texas. In the meantime, Smith paroled most girls to ease overcrowding. For those who stayed, she implemented legitimate classroom instruction, leisure activities, and even a system in which girls received brass discs as payment for chores that could be spent at a small store.[8] In February 1937, Eleanor Roosevelt paid a return visit and was overjoyed by what she saw. “There’s light and air, and there are no bars on the windows,” she told the Evening Star. “I would not have known it to be the same place.”[9]

Then it all fell apart. The precipitating incident took place in June in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, where Black boxing phenom Joe Louis won the heavyweight title from White fighter James Braddock. After the match, one of the few White girls at NTS got into a fight with a Black peer over the outcome. It escalated into a full riot that required police to quell. Smith said the incident was a symptom of the nation’s racial strife, remarking that “there is no problem in America more urgent than understanding and sympathy between the two races.”[10] But then in September, it happened again. Black girls rioted when their African American sewing teacher was replaced by a White woman. The Board of Public Welfare decided to wash its hands of Smith, and summarily fired her.[11]

But Smith would not go quietly, especially when she saw D.C. officials slash the NTS budget and return to the punitive practices she had worked to eliminate. She reached out to Eleanor Roosevelt, her highest profile supporter. In a hand-written letter, Smith said she would not leave Washington before “getting a chance to have the whole situation brought to the light of day.” She asked the First Lady to set up public hearings on her time in office.

Mrs. Roosevelt agreed. In a note to her husband, Eleanor wrote “She deserves a hearing. What should I do?” When the president dragged his feet, the First Lady took care of it herself. Through her allies in Congress, Roosevelt forced the Board of Commissioners that ran D.C. to discuss the case against Smith in public. Carrie Weaver Smith would have her day in court.[12]

The Smith hearings began on May 23, 1939, over a year and a half after her firing. The Board of Public Welfare made it clear that they had no plans to vindicate their dismissed superintendent. They appointed Oliver Gasch, the city’s assistant corporation counsel, to “prosecute” Smith. Over five days, Gasch called 24 witnesses against her, and the sensational charges they made rocketed the trial onto the pages of Washington’s newspapers.

According to NTS staff, Smith instituted a policy of “passive therapy” that barred them from disciplining the girls, who supposedly ran rampant with knives and clubs. Social worker Emily Koehler testified that the inmates were never forced to follow venereal disease treatment plans, and were even fed “porterhouse steaks, pork, and lamb chops.” Most scandalously, some staff said that Smith did not oppose the lesbian relationships that formed among the girls. Blindsided by the accusations, Smith quipped that “it’s a wonder the Board of Public Health didn’t hang me instead of just firing me.”[13]

The criticisms of Smith revealed the fundamental difference between how she and the rest of Washington understood NTS. Where Smith saw girls needing reform, the Board of Public Welfare and most NTS staff saw a danger that needed to be contained. Girls avoiding treatment for venereal disease was not a sign of lax discipline, but a threat to public safety. One D.C. police officer said he was “disgusted” to hear Smith call the girls “darling” and “sweetheart” when they should have been punished. Though kept below the surface during the hearings, racism infused this difference of views. Black girls simply were not worth saving. As Rep. Ross Collins said just before the hearings, “my constituents wouldn’t stand for spending all that money on n*ggers.”[14]

After days of vicious attacks, the Washington Post was done with the farce. In an editorial denouncing the biased and unproductive proceedings, the paper lamented that “only in the impotent District of Columbia is a fiasco of this sort likely to be found.”[15] But Smith was undeterred, even when the Board of Commissioners blocked her from discussing the theory behind her policies in open court. She assembled her own cadre of witnesses, including the head of the federal Children’s Bureau, to defend her record. Smith argued that “the spirit of leniency is the foundation of all discipline,” and compared the school’s reputation under her leadership to the “antediluvian” conditions she undid.[16]

After four weeks, the hearings finally concluded. The Evening Star called them “some of the most frank testimony ever heard in the district building.” The Board of Commissioners, though, was unmoved. With little fanfare, they confirmed Smith’s “dismissal with prejudice.” They cited her seeming acceptance of “immorality” (meaning same-sex relationships) and the laxity of venereal disease treatment. At NTS, things were to go back to the way they were before Smith took over.[17]

With the verdict, Smith retired and opened a small bookstore near the White House. Her departure was not an isolated event. As more Black boys and girls entered juvenile systems in the 1930s, the values of compassionate, if authoritarian, reform that had once guided them faded away. More punitive principles took their place, as many states pushed African American children into the adult criminal system and abandoned traditional notions of juvenile justice altogether.[18] In Washington, Black girls at NTS continued to receive poor education in decaying buildings until the facility was finally closed in 1953. In the halls of power, no one seemed to care.

Footnotes

- ^ William S. Bush, Who Gets a Childhood?: Race and Juvenile Justice in Twentieth-century Texas. (Athens, Ga: University of Georgia Press), 2010, 22-25.

- ^ “Children’s Homes Held Deficient,” Evening Star, March 24, 1936, A10. “Girls’ Training School Conditions Shock Senate Committee,” Evening Star, March 29, 1936, B1. “Dr. Smith Cites Escape Figures in Plea for Training School,” Evening Star, May 17, 1936, A5.

- ^ Memorandum to D. W. Bell, October 9, 1936, Record Group 51, 21.1, Box 70, Records of the Bureau of the Budget, National Archives, College Park. Eleanor Roosevelt, My Day, May 8, 1936. “Girls’ Training School Conditions,” Evening Star. Gerald G. Gross, “Home for Girls is ‘Barbaric,’ Copeland Finds,” Washington Post, March 29, 1936, 1.

- ^ Mary E. Odem, Delinquent Daughters : Protecting and Policing Adolescent Female Sexuality in the United States, 1885-1920, Gender & American Culture, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995). Tera Agyepong, The Criminalization of Black Children: Race, Gender and Delinquency in Chicago's Juvenile Justice System, 1899-1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 71-72.

- ^ Bush, Who Gets a Childhood, 22-25. “‘Breaks’ Blamed for Delinquency,” Evening Star, May 18, 1936, A18.

- ^ For discussion of unequal racialized accommodation for black children, see Bush, Who Gets a Childhood?

- ^ For description of the unequal access afforded to Black delinquents, see U.S. Congress, Senate, Subcommittee for District of Columbia Appropriations, District Of Columbia Appropriation Bill For 1940, May 23, 1939, 76t Cong., 1s Sess., 1939, 742, statement of Rufus S. Lusk; U.S. Congress, Senate, Subcommittee for District of Columbia Appropriations, District Of Columbia Appropriation Bill For 1939, Feb 8, 1938, 75t Cong., 3d Sess., 1939, 742, statement of Julia Hamilton. For a breakdown of NTS inmates and their venereal disease history, see U.S. Congress, House, Subcommittee for District of Columbia Appropriations, District Of Columbia Appropriation Bill For 1939, Jan 12, 1938, 75t Cong., 3d Sess., 1939, 488-490.

- ^ “Training School Girls ‘Support’ Selves with Brass Money Pay” Evening Star, Aug 31, 1936, B1; Hope Ridings Miller, “More Poetry, Less Politics Urged for ‘Problem’ Girl,” Washington Post, May 15, 1935, 14; Hope Ridings Miller; “Time for New Reform says Dr. Carrie Smith,” Washington Post, Mar 21, 1936, 17; Hope Ridings Miller “Girls' Training School, Once Gloomy, Now Aid to Creative Living,” Washington Post, Mar 28 1937, B7; Minutes of the Board of Public Welfare, Sep 29, 1936, Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, Record Group 351.6, Entry 160, Box 1, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- ^ “Mrs. Roosevelt, On Tour, Praises Training School,” Evening Star, February 4, 1937, B1.

- ^ “Girls’ Home Head Quizzed on Riot” Evening Star, Jun 25, 1936, A2; “Police Quell Reformatory Girls' Melee: 8 Colored Inmates Arrested” Washington Post, Jun 25, 1936, 11; “Girls Riot Over Louis Braddock Fight,” Chicago Defender, July 3, 1937, 5.

- ^ “Dr. Carrie W. Smith Dismissed as Head of Training School,” Evening Star, October 19, 1937, A1. Minutes of the D.C. Commission, Oct 29, 1937, Records of the Government of the District of Columbia, Record Group 351, PI-186, Entry 14, National Archives, Washington D.C.

- ^ Records of the Bureau of the Budget, Record Group 51, 21.1, Box 70, National Archives, College Park.

- ^ “Lax Morality Charge Aired at Smith Hearing,” Evening Star, May 23, 1939, B1. “Smith Hearing Witnesses Tell of Rioting,” Evening Star, May 24, 1939, B1. “Testimony to Continue Against Dr. Smith into Next Week,” Evening Star, May 25, 1939, B1. “Unauthorized Paroles Laid to Dr. Smith,” Evening Star, May 27, 1939, B1. Smith quote from “Dr. Smith Plans to Present Her Defense Today,” Evening Star, June 13, 1939, B1.

- ^ Constance McLaughlin Green, Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital, (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 1967, 458.

- ^ “Futile Hearing,” Washington Post, May 27, 1939, 8.

- ^ “Theory Evidence is Rejected in Smith Hearing,” Evening Star, June 1, 1939, B1. “Miss Lenroot Defends Training School Methods,” Evening Star, June 5, 1939, B1. “Dr. Smith Plans,”Evening Star. “Dr. Smith Hits Tydings, Lee as ‘Interferers,’” Evening Star, June 14, 1939, B1.

- ^ “Dr. Smith’s Ouster Stands, Commissioners Decide,” Evening Star, June 27, 1939, A1, A4.

- ^ Agyepong, Criminalization, 96.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)