What's in a Name? Virginia

There was once a time when the entire Eastern Seaboard was known (to Europeans and settlers) as “Virginia.” Maps from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries show that English settlers didn’t really set out clear borders when they first arrived in North America, since they had no idea just how large the continent is. They completely ignored the borders of indigenous nations. Once they landed, the entire area around them—whatever it looked like, whoever already lived there—was claimed for Queen Elizabeth I of England. It may be a bit hard to tell, but this queen is actually the namesake of the colony—and future state.

In the 1580s, almost a century after the journey of Christopher Columbus sparked the European colonization of the Americas, Spain was England’s greatest rival for power. The spoils of wars and conquest had made Spain incredibly wealthy—although English pirates had long been stealing Spanish gold from ships in the Atlantic Ocean. But Queen Elizabeth knew that the best way to challenge Spain was to establish colonies of her own. Her attention turned towards North America, which had been explored and navigated by the English but not permanently settled.

The Queen issued her patent for settlement on March 25, 1584, instructing the explorer Sir Walter Raleigh “to discover, search, find out, and view” land that could be settled by English colonists.[1] Instead of going himself, Raleigh sent two captains, Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, and their crews to complete the mission for him. Preparations were speedy—Amadas and Barlowe departed England in April.

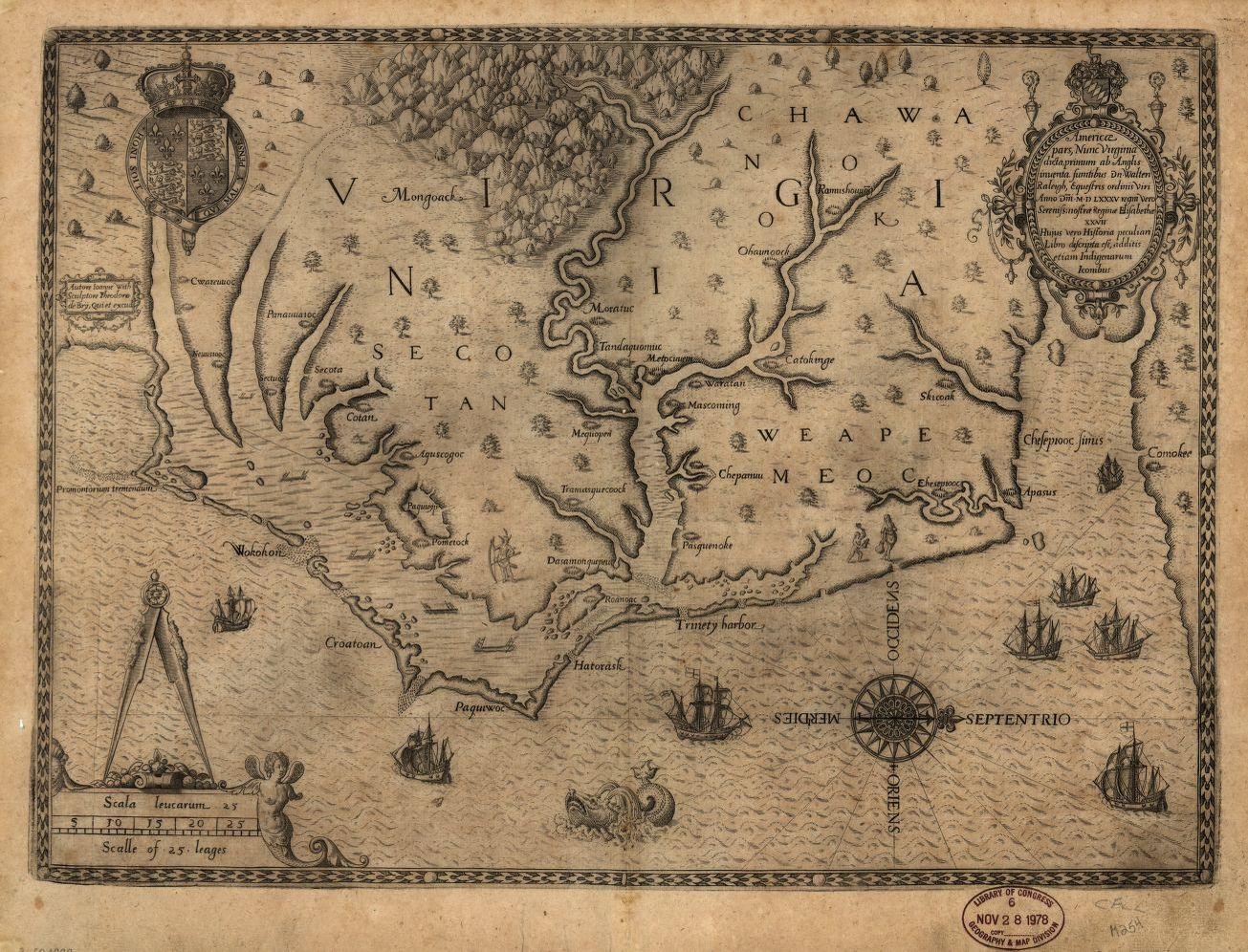

The English expedition sailed first to the Caribbean, following a well-traveled route, before turning north and sailing up the Florida coast. At the time, this was mostly Spanish territory—Amadas and Barlowe knew they needed to find land that was unclaimed by any Europeans. On July 13, 1584, the company landed on Cape Hatteras in North Carolina.[2] Though they didn’t give the area an official name, they claimed it for England and Queen Elizabeth.

But through contact with the local tribes, including the Secotan people, Amadas and Barlowe did learn the local names for the area. Barlowe, especially, took detailed notes based on conversations with indigenous chiefs. Some of the names are still used in North Carolina today: “Hatteras,” for example, or the nearby island “Roanoke.”[3] Barlowe reported (perhaps incorrectly) that the entire area was called “Wingandacoa” by the Secotan, then ruled over by a “wereoance,” or principal chief, named Wingina. Barlowe took these notes back to England, where he presented his findings to Raleigh and Queen Elizabeth.

George R. Stewart, a historian who wrote about American place names in the 1940s, proposed an interesting theory surrounding the naming of England’s North American territory.[4] He believed that, upon reading the name of the Secotan chief, Raleigh decided to put his own spin on the local name—probably to show dominance, rather than honor a potential rival, since colonists killed Wingina a few years later. “Wingina” does bear some resemblance to the name “Virginia,” so it’s tempting to believe Stewart’s theory. But there’s a much more obvious and commonly accepted etymology.

Though remembered as an explorer and adventurer, Raleigh was also a politician and courtier who constantly fought to be noticed by Queen Elizabeth. Hoping to flatter her and win approval, he decided to name the new colony—already claimed in her name—after her. Instead of a straightforward name, Raleigh chose something a bit more poetic. Because she never married and ruled in her own right, Elizabeth was known in England as “the Virgin Queen,” a moniker which inspired the Latin “Virginia.”[5]

Rather than the name of a single colony, “Virginia” was the English name given to all of North America not controlled by the Spanish or French. It was even listed as one of the Queen’s dominions in her title. However ubiquitous, though, it didn’t come to be associated with the area of our modern-day state until the early 1600s. After the early colonial enterprises in North Carolina failed in the 1580s, the English didn’t attempt any further settling until after the death of Queen Elizabeth. In 1606, interest in Virginia was sparked again with the creation of “the Virginia Company,” two joint-stock companies given permission to settle the North American coast. Explorers from the Virginia Company landed in the Chesapeake Bay on April 26, 1607—later establishing their permanent colony, Jamestown, named for King James I.[6]

But Virginians shouldn’t get too cocky—the name didn’t apply to all of British North America for very long. As England (and other countries) established more colonies in North America, the precise location of Virginia began to shift. Jamestown and the surrounding area, the oldest English colonies settled by the Virginia Company, retained the name—colonies to the north, established by other people under other charters, were given names like “New England” or “New Amsterdam.” Colonial names were better established throughout the seventeenth century, as the official boundaries of the colonies surrounding Virginia—Maryland, for example, established in 1632—confined it to the approximate area we know today. In 1788, the state’s name became official when it became the tenth to ratify the United States Constitution.[7]

Perhaps, in some alternate history, the name “Virginia” may have applied to our entire country—for a time, that was certainly the case. But Virginians can rest easy knowing that their state name definitely holds some prestige, since it’s one of the oldest English place names in the country.

Footnotes

- ^ “Charter to Sir Walter Raleigh, 1584,” The Avalon Project, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/16th_century/raleigh.asp

- ^ The Roanoke Voyages, 1584-1590 1, ed. David Beers Quinn (Ashgate, 1952), 79.

- ^ George R. Stewart, Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-naming in the United States (New York: Random House, 1945), 22.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Questions about Virginia,” The Library of Virginia, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/faq/va.asp

- ^ “A Short History of Jamestown,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-short-history-of-jamest…

- ^ “History of Virginia,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Virginia-state/Independence-and-stateh…

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)