What's in a Name? The Potomac River

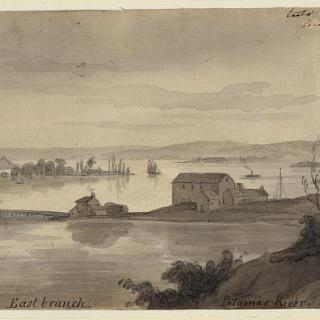

There have been many names for the Potomac River. In our country’s history, it’s been called the lifeblood of the capital city. George Washington—who grew up and later planned his namesake city on its banks—called it the “Nation’s River.”[1] Almost two centuries later, Lyndon B. Johnson called its badly-polluted waters “the national disgrace.”[2] Nowadays, to most Washingtonians, it’s probably just “the river.”

But all nicknames and epithets aside, the Potomac actually has a complicated naming history. Though the name is of American Indian origin, historians can’t really agree on its exact meaning. It’s been called a lot of different names, depending on who you talked to. And, until 1931, most people weren’t even sure how to spell it.

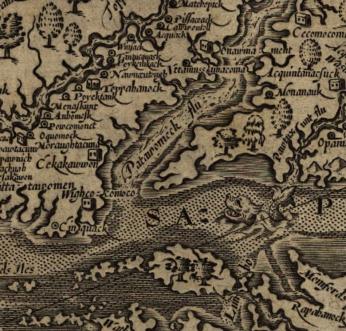

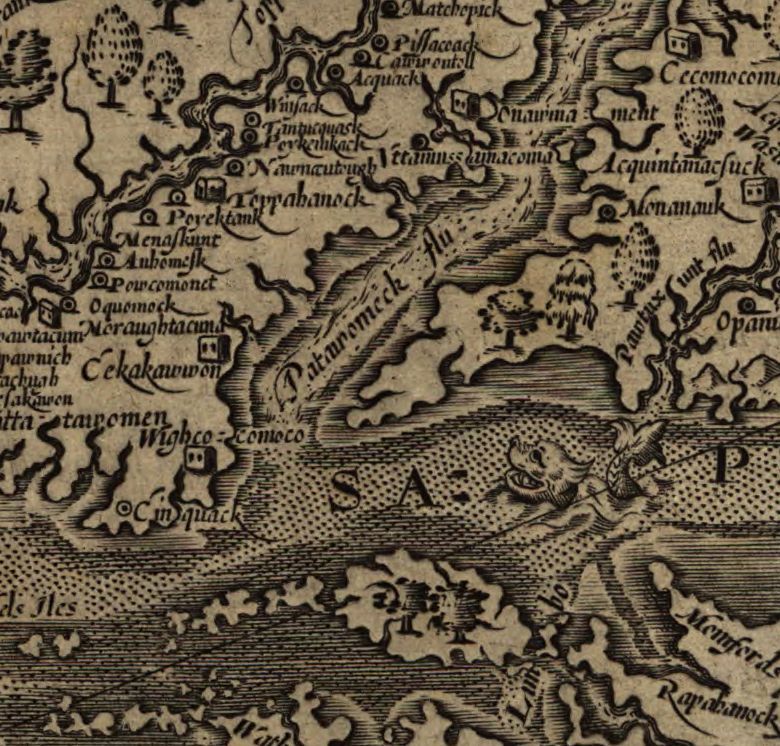

The river’s name first entered English through Captain John Smith, the Jamestown settler and explorer. His book A Map of Virginia, with a Description of the Country, the Commodities, People, Government and Religion, published in 1612, gives us our first glimpse of the Potomac in recorded history:

“The fourth river is called Patawomeke and is 6 or 7 miles in breadth. It is navigable 140 miles, and fed as the rest with many sweet rivers and springs, which fall from the bordering hills. These hills…are planted, and yield no less plenty and variety of fruit that the river exceedeth with abundance of fish.”[3]

The river derives its name from an American Indian village on its southern bank, the home of the Patawomeke people.[4] They were a sometimes-ally of the larger Powhatan Confederacy, which controlled most of the territory in the region. Following the founding of Jamestown, the Patawomeke began a mostly friendly relationship with the English settlers—even allying with them against the Powhatan in the First Anglo-Powhatan War of 1612. But as more settlers colonized the area, the tribe lost much of their land and resources. Today, their descendants—the Patawomeck, one of Virginia’s recognized Native American tribes—still live close to the original village in Stafford County.[5]

The meaning of the name “Patawomeke” isn’t known for sure. The tribe spoke a now-lost Algonquin language, like most American Indians of the Tidewater region, so the exact English translation was never recorded. But based on oral tradition, local legend, and knowledge of other regional languages, historians have presented several possibilities.[6] One is “they who come by water,” referring to the tribe’s proximity to the river. “Patawomeke” could also mean “river of burning pine,” “river of swans,” or “river of traveling traders.” But it’s further confused by the fact that the river had several different names with several different meanings, depending on language, tribal jurisdiction, location, and geographical features. The upper part of the river, for example, was known as “Cohongarooton,” or “honking geese.”[7]

Even as European settlers overtook and displaced the native Patawomeke, the river continued to carry many names. For the most part, the original name stuck—sort of. Over many years of Anglicization, the original spelling and pronunciation changed. Somewhere along the way, two syllables were dropped completely. And most writers just spelled the name phonetically, not caring about continuity at all. In a letter from 1784, Thomas Jefferson uses two different spellings on the same page: “Patomac” and “Patowmac.”[8]

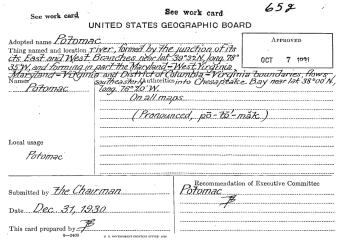

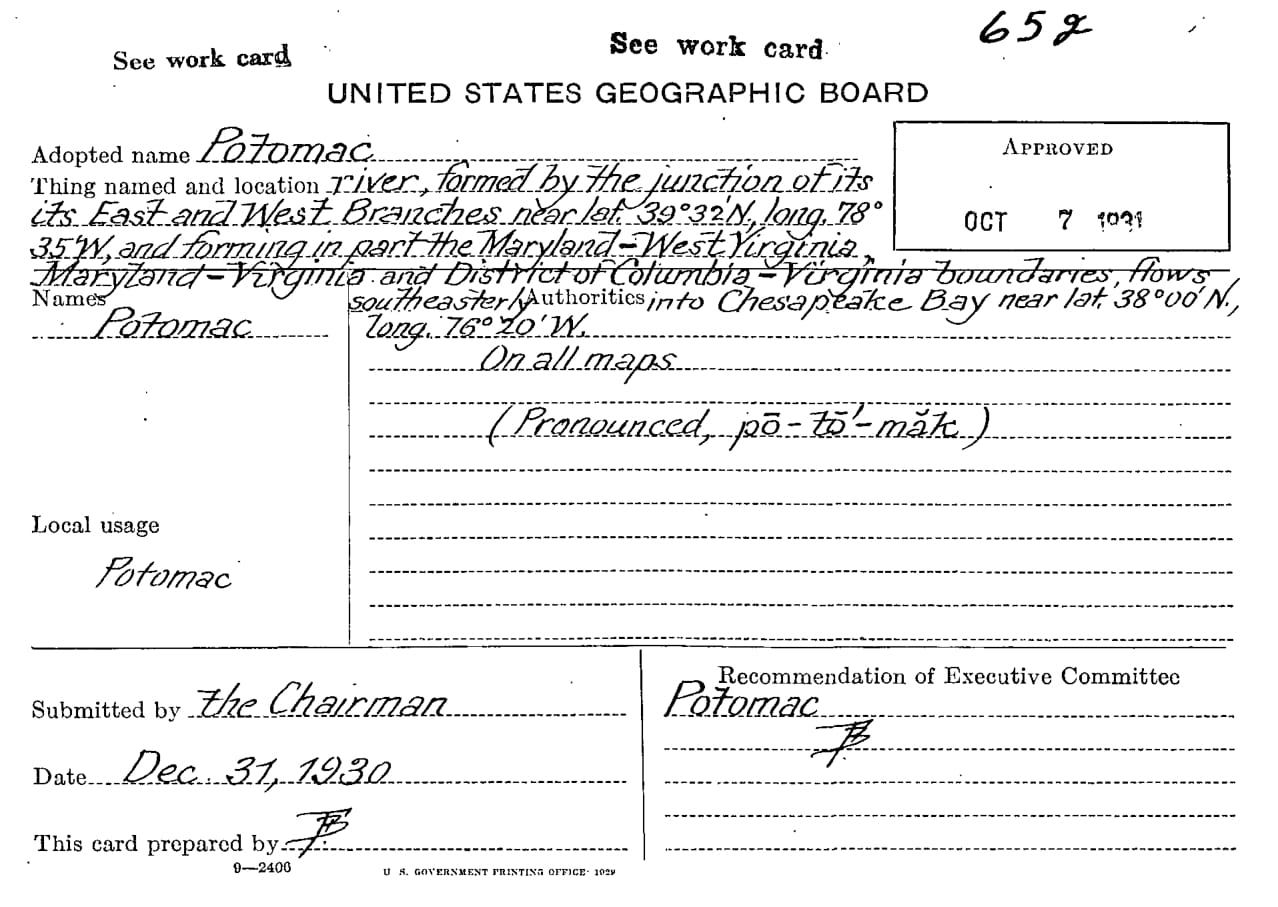

Luckily, our country has a Board on Geographic Names. Formed in 1890, its purpose is to “establish and maintain” the uniform usage of place names, just to avoid any confusion.[9] In 1930, when they finally turned their attention to the Nation’s River, the Board collected nearly ninety-five variant names still in use at the time—versions of traditional American Indian names like “Cohongaroota River,” colloquial nicknames like “Turkey Buzzard River,” and even local family claims like “Elizabeth River.”[10] They also listed dozens of potential spellings of the river’s original name: “Patowomek,” “Potomach,” “Pittomack,” “Pottomeek,” and even “Betomek.”[11] You can read the entire list here.

But, as we know, the Board chose the name, spelling, and pronunciation they felt was most commonly used by locals: “Potomac.” A long way from the original, but still faintly recognizable.

Footnotes

- ^ “Potomac: America’s River,” American Rivers, https://www.americanrivers.org/river/potomac-river/

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John Smith, “A Map of Virginia,” in The Complete Works of Captain John Smith 1, ed. Philip L. Barbour (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 147.

- ^ William Bright, Native American Placenames of the United States (University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 396.

- ^ Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia, http://patawomeckindiantribeofvirginia.org/

- ^ Louise Payson Latimer, Your Washington and Mine (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1924), 262; Joel Achenbach, The Grand Idea: George Washington’s Potomac and the Race to the West (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), 35-36; Bright, 396.

- ^ Achenbach, 35.

- ^ Achenbach, 35.

- ^ “U.S. Board on Geographic Names,” The U.S. Geological Survey, https://www.usgs.gov/core-science-systems/ngp/board-on-geographic-names

- ^ “Feature Detail Report for: Potomac River,” The U.S. Geological Survey, https://geonames.usgs.gov/apex/f?p=gnispq:3:0::NO::P3_FID:597915

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)