The Bank Robberies of Del Ray

Every Saturday, twelve-year-old Roy Thomas had the same morning routine. He would go to the Bank of Del Ray at the corner of Mt. Vernon and Windsor Avenue in the Town of Potomac and deposit $20 for his father. But on the morning of May 4, 1929, when the young boy entered the bank, he got a surprise instead: a pistol aimed at his face.[1]

Thomas had just walked into an active robbery. Only minutes earlier, five bandits, each sporting blue suits and wearing gray caps and gloves, exited a large sedan and entered the bank. Another bandit was left inside the vehicle as the get-away driver.[2] Awaiting them were two bank employees, stenographer Mary Ford and clerk Charles E. Jones, who, at the command of the classic line, “stick ‘em up,” were staring down the barrels of pistols.[3] The robbers then forced them to go inside the bank vault and face the wall with their hands in the air. Both were kept under guard by one of the men while the others went to the front of the building.

It was at this point that the young Roy Thomas entered. Two of the robbers quickly pulled him to a side room, cut up a telephone wire, and tied him to a stool with it.[4] Upon searching Thomas’ pockets, one of the men discovered his $20, made up of small bills. “What’s this?” the man asked him. Thomas responded that he came to deposit it with the bank. “Keep it then,” the man replied. “We don’t want your savings.”[5]

Another customer followed soon after Thomas, who joined Ford and Jones against the wall.[6] But unlike Thomas, the robbers pocketed over a hundred dollars from him.[7] Meanwhile, the other men ransacked the vault, scrounged up over $2,000 in bills, and stuffed them into a small satchel. While they had the opportunity to take $500 worth of silver, they decided it was too heavy to carry, and left it behind.[8]

As they finished their raid, the robbers bid farewell to Thomas, leisurely walked out of the bank, and sped off in the direction of Washington.[9] Soon thereafter, Jones dashed out of the bank and called Police Sergt. A. F. Driscoll and Potomac Mayor W. B. Fulton. Police in Washington, Alexandria, and the surrounding area were placed on alert for the bandits. Roads were blockaded in the Del Ray neighborhood and police in Arlington County were posted at strategic locations. But the attempted cordon failed. The six men escaped capture.[10]

Identifying the robbers proved a fruitless task. While the getaway sedan had D.C. license tags, police later declared them to be “dead tags” and were never able to locate the vehicle.[11] Racial constructions also played a confounding factor, as the witnesses described them as “foreigners” with a dark complexion.[12] However, Thomas described one of the men as a “white man.”[13] A few days later, police linked a raid in northwest D.C., in which six “shabbily dressed” men robbed a drug store, to the same men in the bank robbery, but still, no one was caught.[14]

The final theory by police suggested that the six men were involved in far more violent affairs than initially known, linking them to a shootout at Green Gables roadhouse in Prince Georges County, Maryland that occurred two months earlier.[15] If the information obtained by police was true, then the gang ran a tight operation stretching from D.C. to Philadelphia, with Philadelphia being the location where it would “dispose of its gains,” the Washington Post reported.[16] The leader of the gang was said to rule with a “‘rod’ of iron” and kept the others in line through fear of his “shooting ability.”[17] In the conclusion of its report, the Post hinted that the police hunt was close to an end: “Police believe they will be able to place the gang under lock and key within a short time.”[18]

Yet no new reports ever surfaced in the press. The last mention of the roadhouse shootout suggested a “gang-war” was active in Maryland, but didn’t mention whether the group in the bank robbery was involved.[19] In the end, the bandits got away.

Luckily for the Bank of Del Ray, the stolen money was covered by insurance.[20] And Roy Thomas, for all his trouble, got to author an article about his experience in the Washington Post. “I was scared with that gun so close at my face,” he wrote. “But I did just what the man told me and I guess that’s why they didn’t hurt me. Anyway, I’m glad they didn’t get my father’s money.”[21]

To the public, this was the first time that the Bank of Del Ray was robbed. However, unrelated to the robbers entirely, a much larger crime had been unfolding inside the bank for months.

On January 21, 1930 the bank closed for an audit by State examiners.[22] No reason was given for why the audit took place, but shortly after it began, to the shock of the bank’s managers, it revealed that over $60,000 (around $1,000,000 in 2022 in dollars) had gone missing.[23] According to the Evening Star, “No statement” was made by bank officials “as to how the shortage, which is considered exceedingly large with relation to the size of the bank, had been brought about or what disposition was made of the money alleged to have been embezzled.”[24]

Within days, investigators zeroed in on longtime bank cashier Clay T. Brittle. Given Brittle’s standing in the community, the news “came suddenly and greatly surprised every one, since no action of this sort had been contemplated,” the Star reported.[25]

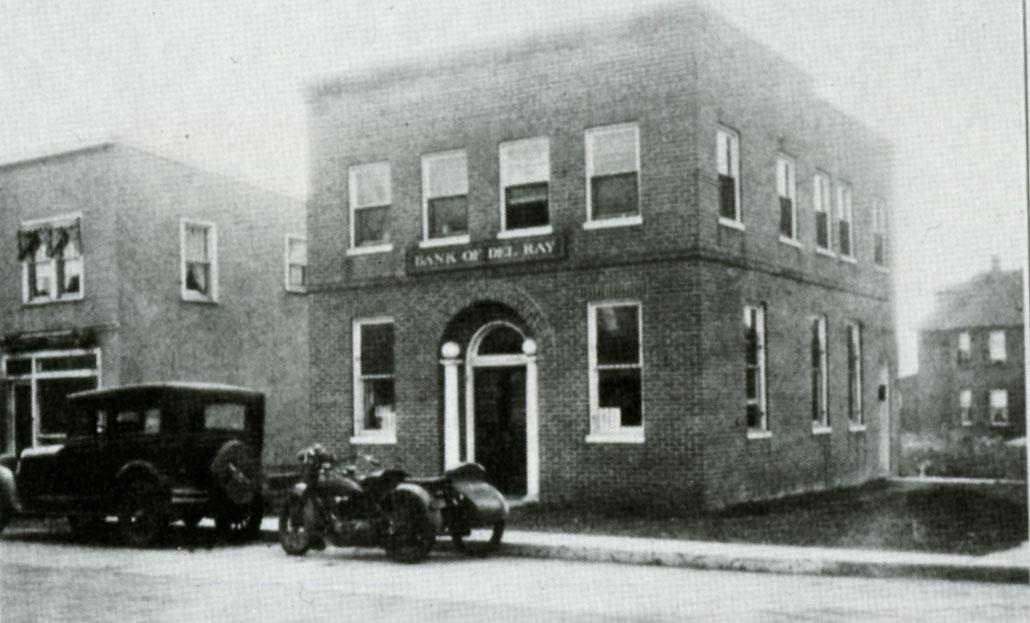

Indeed, Brittle had been attached to the bank as a cashier since its founding in 1923.[26] At the time, the bank was operating out of a drugstore on Mt Vernon Avenue. But soon the bank expanded and opened a $25,000 facility on the southwest corner of Windsor Ave and Mt Vernon Ave—which the six bandits would rob in May 1929.[27] (Ironically, on the day of the robbery, Brittle had just exited the bank before the robbers entered.)[28]

A veteran of the First World War, Brittle was very popular in Alexandria's social and civic circles.[29] He was well known for his talent at shooting clay pigeons as president of the Alexandria Gun Club, and the happenings of Brittle and his family were frequently recorded in the Washington Post’s “Keeping in Touch with the Suburbs” section and other features of local society.[30] Among these recorded activities were a visit to relatives, attendance of a Thanksgiving night dance, and a family trip to Old Point, Virginia.[31]

However, it seems that Brittle also had a secret: For months, he had kept a double set of bank ledgers and embezzled money.[32] Under the scrutiny of the audit, the scheme fell apart. A warrant for Brittle’s arrest, sworn by both the president of the bank and a member of its board of directors, went out on January 29, 1930.

Arrangements were made by Brittle’s friends to pay for his bond, set at $25,000.[33] While Brittle awaited his grand jury hearing, the bank continued its audit and promised its over 900 defrauded depositors (many of whom were embarrassed by the bank’s temporary closure) that they would have their money refunded.[34] Yet the task proved more difficult than expected. While the audit finished by the end of February, the bank still hadn’t refunded all of its depositors. It soon sought after a bank receiver who would take charge of the bank's assets and “protect the public interest,” the Washington Post reported.[35] Once hired, the receiver worked diligently to repay all depositors and was briefly able to open the bank in March for the sole purpose of repaying a portion of deposits.[36] Yet the bank's financial dilemma was far from over.

Meanwhile, Brittle, to help produce a more favorable case from himself—and, it seems, to make genuine personal amends for his crime—turned over part of his real estate to the bank in partial restitution.[37] In June, he was handed 13 indictments charging grand larceny after trust, but his lawyer was able to dismiss twelve of them and got the judge to accept a six-year prison sentence instead.[38] According to the Post, the judge, as part of his acceptance of the substitute, noted that Brittle had “come forward voluntarily in turning over to the bank’s directors his real estate holdings, approximating a substantial part of the losses, and that he had made restitution to the best of his ability,” commending him for his efforts to make amends.[39]

As part of Brittle’s six-year sentence, to which he pleaded guilty, he was subject to work on a convict “road gang.” He was also given the options of an early release after four years of good behavior or a pardon after serving half the sentence.[40]

Unfortunately for the Bank of Del Ray, its finances never returned to order and the bank shut its doors for good. The combination of Brittle's embezzlement scheme, the bank's messy finances, and the emerging conditions of the Great Depression made it nearly impossible to finish repaying the bank's depositors. By August 1931, eighteen months after the bank first closed, the receiver was still “unable to say” when his task would be accomplished, the Post reported. Surely the "present condition of the real estate market” (a phrase, it seems, used as a euphemism for the growing economic catastrophe slamming the country), didn't help.[41] Of the 900 or so depositors awaiting restitution, only 43 cents per dollar of their total deposits were ever repaid.[42] Brittle, meanwhile, was busy serving his sentence at Richmond Penitentiary.[43]

After the bank shut down in the 1930s, the building at the corner of Mt. Vernon and Windsor Ave came to house a loan company. By the 1940s, was used as the office for a real estate agent.[44] Today, the building is home to the colorful Thai Peppers restaurant, where customers can enjoy a warm meal with the option of patio seating.

Footnotes

- ^ Roy Thomas, “Boy Bank Robbery Witness Writes His Story of Holdup,” Washington Post, May 5, 1929.

- ^ “Six Bandits Loot Bank at Del Ray of $2,000 in Cash,” Evening Star, May 4, 1929; “Six Bandits Sought After Bank Holdup,” Washington Post, May 5, 1929.

- ^ “Six Bandits Sought.”

- ^ “Six Bandits Loot Bank.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Six Bandits Sought.”

- ^ “Del Ray Bandits Are Sought Here,” Evening Star, May 5, 1929.

- ^ “Six Bandits Loot Bank.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Six Bandits Sought.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Thomas, “Boy Bank Robbery.”

- ^ “Bank Gang is Linked to Drug Store Raid,” Washington Post, May 7, 1929.

- ^ “Police Hunt Man Who Shot Two in Quarrel Over Woman,” Washington Post, March 21, 1929. The roadhouse killing, coupled with public outrage at roadhouse violence in general, resulted in Prince Georges County effectively outlawing all applications for roadhouse licenses in July, see “Prince Georges Announces Ban on Roadhouses,” Washington Post, July 3, 1929.

- ^ “Roadhouse Gunmen Held Bank Robbers,” Washington Post, May 12, 1929.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Mystery Shooting Seen as Gang War,” Washington Post, May 28, 1929.

- ^ “Del Ray Bandits”; “Del Ray Hopes to Pay Depositors,” Washington Post, January 22, 1930.

- ^ Thomas, “Boy Bank Robbery.”

- ^ “Del Ray Bank Hopes to Pay Depositors,” Washington Post, January 22, 1930.

- ^ “Cashier of Del Ray Bank is Arrested,” Washington Post, January 30, 1930.

- ^ “Cashier of Del Ray Bank is Arrested,” Evening Star, January 30, 1930.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “800 Alexandrians Facing Penalties for Unpaid Taxes,” Washington Post, July 8, 1923.

- ^ “Potomac’s Election Brings Victory to ‘Law, Order’ Ticket,” Washington Post, June 11, 1924.

- ^ “Six Bandits Sought.”

- ^ “Cashier of Del Ray Bank is Arrested,” Washington Post, January 30, 1930.

- ^ “Alexandria Gun Club Will Elect Officers,” Washington Post, February 9, 1928.

- ^ “Keeping in Touch with the Suburbs: Potomac, Va.,” Washington Post, June 7, 1925; “Keeping in Touch with the Suburbs: Alexandria,” Washington Post, November 27, 1927; “Col. Peyton Relieved of Duty in Alexandria,” Washington Post, July 7, 1929.

- ^ “Cashier of Del Ray Bank is Arrested,” Washington Post, January 30, 1930.

- ^ “Del Ray Cashier Given Six Years,” Evening Star, July 8, 1930.

- ^ “Shut Bank May Pay Off in Two Weeks,” Washington Post, February 1, 1930.

- ^ “Dividend Promised by Bank of Del Ray,” Washington Post, February 28, 1930.

- ^ “Cost of Annexation Told By Alexandria,” Washington Post, March 21, 1930.

- ^ “Brittle Case to Go To Alexandria Jury,” Washington Post, June 18, 1930.

- ^ “Grand Jury Indicts Cashier at Del Ray,” Washington Post, June 20, 1930; “Term of Six Years Given Bank Cashier,” Washington Post, July 9, 1930.

- ^ “Term of Six Years.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “David Still Trying for Bank Wind-Up,” Washington Post, August 15, 1931.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Amy Bertsch and Lance Mallamo, “Bank of Del Ray,” Alexandria Times, August 13, 2009, https://media.alexandriava.gov/docs-archives/historic/info/attic/2009/a….

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)