When the Washington Post Covered Up a Presidential Scandal

In the early 1970s, the Washington Post brought down a president. Beginning with a break-in at the Watergate Office Building, Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein spent years unravelling a web of criminal activities perpetrated by Richard Nixon and his allies. Amid threats from the White House, publisher Katharine Graham supported Woodward and Bernstein as they uncovered the biggest scandal in American political history. The stories they published helped force President Nixon to resign in August 1974.[1]

But five decades before Watergate, another presidential scandal rocked Washington with almost equal intensity. In the 1920s, Warren Harding’s administration was consumed by the Teapot Dome Affair, when Interior Secretary Albert Fall leased away the Navy’s oil reserves in exchange for bribes. But far from helping crack Teapot Dome open, the Washington Post took a different tack. They helped cover it all up.

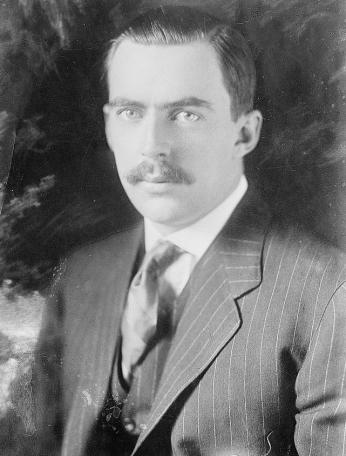

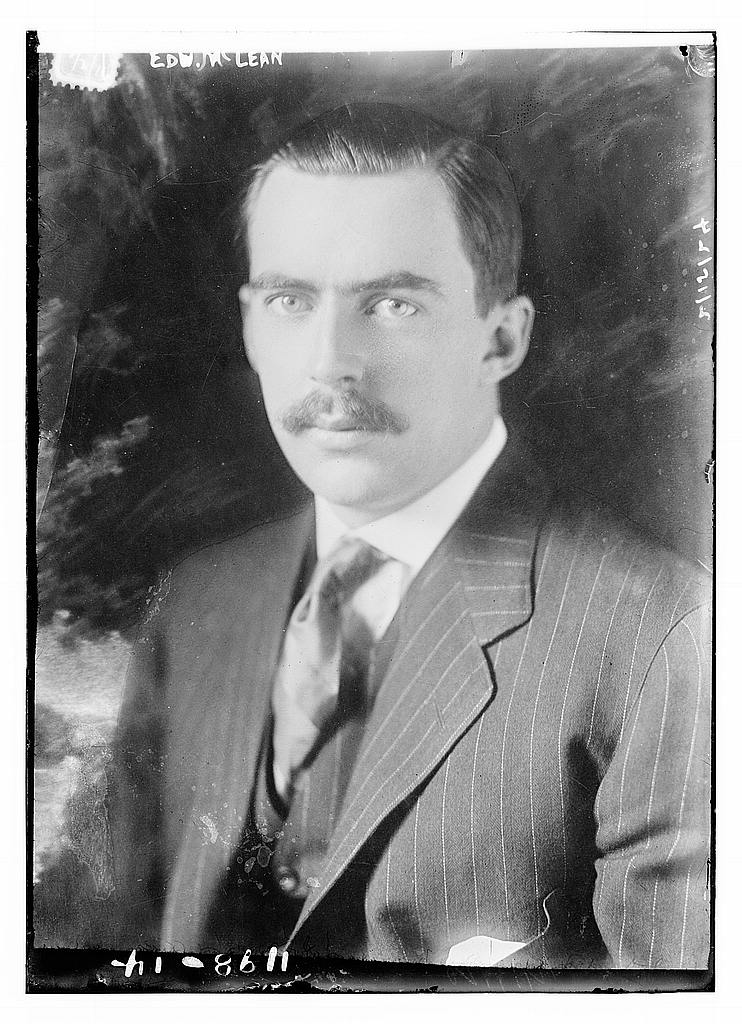

The man who entangled the Post in Teapot Dome was the paper’s publisher, Ned McLean. As Alice Roosevelt later quipped, Ned was a man with “no chin and no character.” He was the only son of John R. McLean, who owned the Post and Cincinnati Enquirer and lent his name to McLean, Virginia. Raised in his family's mansions in Ohio and D.C, Ned fulfilled every stereotype of third-generation wealth. His mother bribed other boys to let him win at baseball and other games and never pushed him to acquire a real education. By 21 Ned had a notorious alcohol habit and a young bride, mining heiress Evalyn Walsh. When Evalyn wanted to wear the Hope Diamond, Ned used his father’s money to buy it for her.[2]

John McLean died in 1916, and he did everything he could to keep his son from squandering the McLean family fortune, which was valued at over $200 million in today’s money. He stipulated that none of his properties could be sold until 20 years after Ned’s own children were dead, and what income they generated Ned would only receive in monthly installments. John did not even make his son a trustee of the estate. Even after hiring the best lawyers in Washington, Ned failed to break his father’s will, but he did secure a consolation prize. He could take charge of the Washington Post.[3]

Generally, Ned left the Post alone as he pursued his passions: golf, horse racing, and excessive partying. Among his closest drinking buddies was a fellow newspaper publisher and Ohio transplant, Warren Harding. Harding and his wife Florence came to Washington in 1915 after Warren won a Senate seat, and the two became fast friends with the younger (but much better connected) Ned and Evalyn McLean. As the New York Times reported in 1921, “the McLeans made the Hardings a part of Washington ‘society.’” They ate together, shopped together, vacationed together, and the Hardings became staples at Evalyn McLean’s opulent parties.[4]

Ned’s father John had been an ardent Democrat, but when Warren Harding became the Republican nominee for president in 1920, Ned threw the power of the Post behind his friend. Harding clinched the presidency and gave Ned the honor of leading the inaugural committee, while Evalyn accompanied the First Lady-to-be on a New York shopping trip days before the ceremony. Once Harding had moved into the White House, he still partied at “the Love Nest,” one of Ned’s properties on H Street that was stocked full of booze and women. After controversially vetoing bonuses for World War I veterans in 1922, the president even slipped out of D.C. to cruise with Ned on his houseboat in Florida.[5]

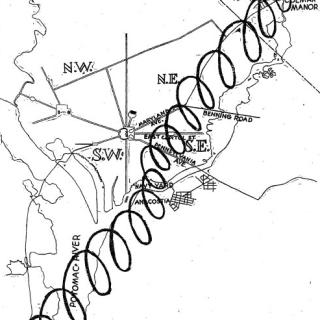

But while Harding caroused with Ned, his other friends robbed taxpayers blind. From the house he rented from McLean at 1509 H Street NW, Attorney General Henry Daugherty arranged kickbacks schemes of all shapes and sizes.[6] Albert Fall was even more flagrant. A former New Mexico senator and poker buddy of Ned and Harding, Interior Secretary Fall convinced the Department of the Navy to give him control of reserve petroleum fields at the Teapot Dome in Wyoming. In exchange for hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash and loans, Fall gave non-competitive leases to the fields to his contacts in the oil industry.

But Fall did not do a good job covering his tracks. Within months of the deal, rumors flew around Washington about his illegal dealing. A Senate committee began looking into the leases, but was stymied at every turn by evasive witnesses and disappearing evidence.[7] Ned’s Washington Post, which he had instructed to focus only on “stories carrying the personal element, social, sporting” and carefree aspects of life, did nothing to investigate. In fact, when President Harding died of a heart attack in summer 1923, the McLeans invited Florence Harding to burn undesirable records in their fireplace.[8]

But Harding’s death did not stop the slow unravelling of Fall’s fraud. At the end of 1923, investigators discovered that the interior secretary had received $100,000 from some unknown source. In reality it came from oil baron Edward Doheny, but Fall invented a more palatable story. He could tell Congress that his fabulously wealthy friend Ned McLean gave it to him. Without hesitation, McLean agreed to back the story. Fall told the tale to investigators, and the whole momentum of the Teapot Dome investigation seemed to evaporate in days.

But then it all fell apart. Sen. Thomas Walsh, the lead investigator into the scandal, was dating one of Evalyn McLean’s friends, and knew something about Ned that even the publisher’s drinking buddies did not realize- he was totally broke. Ned spent every penny from his father’s estate almost as soon as he received it each month. There was no way he ever had $100,000 on hand to loan.

When Ned learned that Walsh was on to the lie, he put the Washington Post to work for his case. From a vacation spot in Palm Beach, McLean instructed the Post’s editor in chief Ira Bennett to lobby senators and do anything possible to keep him out of the witness chair. Ned even used his access to the Department of Justice’s codebook, shared with him by Harding, to send secretly coded messages with Post staff keeping him aware of the situation.

But he could not stymie Walsh, who came down to Florida to interview him. It only took a handful of questions for Ned’s story to implode. He said he wrote Fall a check, but that he had no record of it. Realizing the obvious hole in his story, Ned impulsively said that Fall had returned the check right after he wrote it. But that just defeated the whole point of claiming he had loaned Fall the money.[9]

Knowing he had been lied to, Walsh decided to humiliate Ned publicly. He subpoenaed McLean’s bankers, who testified as to just how little cash he really had. When Ned was compelled to testify alongside the Post employees he had roped into the scandal, he admitted he had lied about the loan and had never given Fall a cent. In an effort to deflect attention from their publisher, the Washington Post headline for the next day declared “E.B. McLean Answers Clearly and Frankly All Questions of Oil Investigators.” But it fooled no one. As Post reporter Chalmers Rogers later wrote, “Washington, and the nation, was laughing at Ned McLean.”[10]

McLean’s involvement in Teapot Dome effectively destroyed the Post. The testimony of Ned and its other leaders shredded the paper’s credibility as an impartial news source. Things only got worse when Ned hired George Harvey, a G.O.P pundit, to edit the editorial page, which Harvey turned into a comically one-sided Republican mouth-piece that ignored Teapot Dome. Subscriptions and ads evaporated. The Post went from being the second ranked paper in the capital, barely eclipsed by the Evening Star, to the least read and most reviled of Washington’s five daily papers. It could only afford to print 12 pages each day. When asked what Washington journalists thought of the Post, liberal editor Oscar Villard said that D.C. press “despise, dislike, and distrust it; to them it is not only a poison sheet, it is also a contemptible one.”[11]

The Great Depression finally took the Post out of Ned McLean’s hands. Wracked by debt, alcoholism, and a nasty divorce, Ned was stripped of editorial control in 1931, and creditors put the paper up for auction. Evelyn McLean tried to buy the paper back, even showing up to the auction wearing the Hope Diamond, but she was outbid by Eugene Mayer, a former member of the Federal Reserve.[12] It was not easy or cheap, but Mayer slowly rebuilt the dignity of the Post.

When Watergate hit, the new leadership of the Post did not make the same mistake as Ned McLean. Mayer’s daughter Katharine Graham resisted every demand to back off the scandal and dug into the corruption with unflinching resolve. Where Teapot Dome had once turned the Post into a pathetic joke, Watergate transformed it into one of the most respectable, successful, and stable publications in the English-speaking world.

Footnotes

- ^ Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, All the President's Men, 40th Anniversary Edition, (New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2014).

- ^ Chalmers M. Roberts, The Washington Post: The First 100 Years, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1977), 134-145, quote on 176. Martin Walker, Powers of the Press: Twelve of the World's Influential Newspapers, (New York: Pilgrim Press, 1983), 246.

- ^ “Estate Kept Intact by Will of Mr. McLean,” New York Times, June 13, 1916, 19. “John R. M'lean's Son Sues To Break Will,” New York Times, July 8, 1916, 9. “Loses Fight to Get M’Lean’s Letters,” New York Times, July 18, 1916, 17. “E.B. McLean Dies; Ex-Publisher 58,” New York Times, July 28, 1941, 13.

- ^ Carol Felsenthal, Power, Privilege, and the Post: The Katharine Graham Story, (New York: Putnam's, 1993), 53-54. “Washington's Social ‘400,’” New York Times, January 16, 1921, 21. Shirley Povich, All Those Mornings, (New York: Public Affairs, 2005), xxiii.

- ^ Walker, Powers of the Press, 247. “Mrs. Harding Arrives to Rest and Shop,” New York Times, January 31 1921, 4. “Harding Veto Impends For The Bonus Bill,” New York Times, March 22, 1922, 2. Laton McCartney, The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding White House and Tried to Steal the Country, (New York: Random House, 2008), 83.

- ^ McCartney, Teapot Dome, 92.

- ^ McCartney, Teapot Dome.

- ^ Roberts, Washington Post, 158. McCartney, Teapot Dome, 178.

- ^ McCartney, Teapot Dome, 202-214.

- ^ “No Mission,' Says Slemp,” New York Times, February 26, 1924, 1. “Publisher Ignored Hint: Burns Indirectly Urged Mclean To Drop $1 A Year Job,” New York Times, March 5, 1924, 1. “Publisher Explains ‘Loan,’” New York Times, March 13, 1924, 1. Roberts, Washington Post, 172-176.

- ^ Roberts, Washington Post, 176. Walker, Powers of the Press, 248. Felsenthal, Power, 51.

- ^ Walker, Powers of the Press, 248-249. Roberts, Washington Post, 186-193.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)