George Washington’s Final Command

All George Washington wanted to do was retire. After his second term as president ended in 1797, he went home to Mount Vernon, fully intending to return to his 8,000 acre estate[1] and avoid public life.[2]

That didn’t last long.

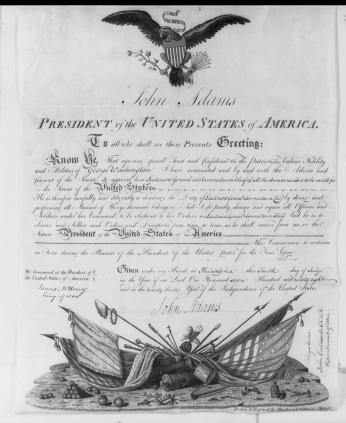

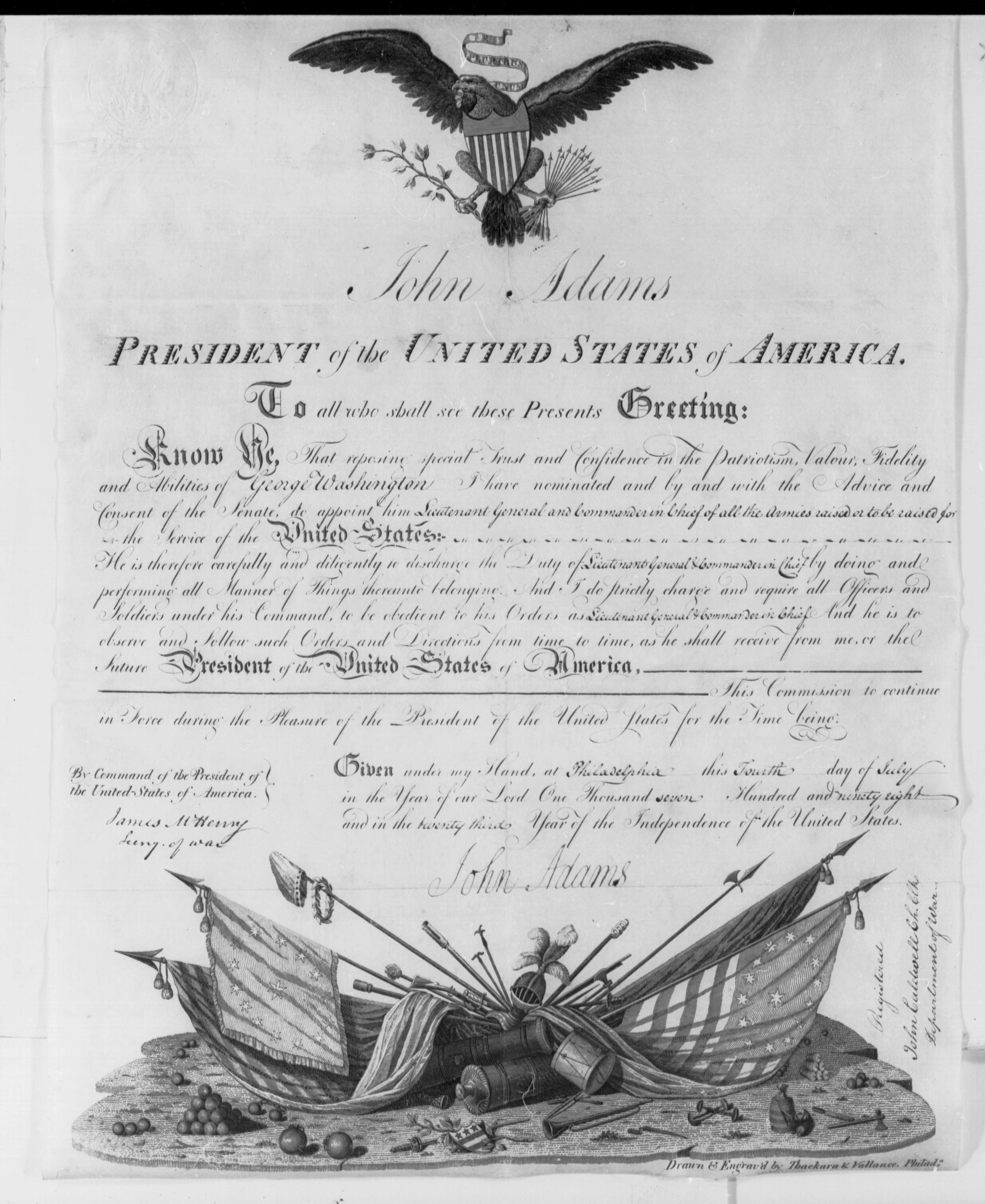

On July 4, 1798, as tensions between the United States and France were heating up, President John Adams appointed Washington as Lieutenant General and Commander-in-Chief.[3] Never mind the fact that Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution explicitly assigned that job to Adams, or that Washington was enjoying his retirement and was not looking for a job.

With the nearest post office about nine miles away, news took its time to reach Mount Vernon,[4] so Washington didn’t find out about his new job until July 11. Two days later, he wrote to Adams.

“I cannot express how greatly affected I am at this new proof of public confidence, and the highly flattering manner in which you have been pleased to make the communication; at the same time I must not conceal from you my earnest wish, that the choice had fallen on a man less declined in years, and better qualified to encounter the usual vicissitudes of war.”[5]

Washington was 66 and he had already retired from Commander-in-Chief twice; once at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783 and again at the end of his second term as president in 1797.[6] Accepting this job would put him at the top of the young nation’s armed forces for the third time. Other than Adams’ brief stint from March 4, 1797 to July 4, 1798, Washington was the only Commander-in-Chief the American forces had ever known.

In his letter to Adams, Washington continued:

“Thinking, in this manner, and feeling how incumbent it is upon every person of every description to contribute at all times to his country’s welfare, and especially in a moment like the present, when every thing we hold dear is so seriously threatened, I have finally determined to accept the Commission of Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the United States; with the reserve only, that I shall not be called into the field until the army is in a situation to require my presence, or it becomes indispensable by the urgency of circumstances.”[7]

By the time Adams commissioned Washington, the Quasi-War with France was already underway. Adams revealed the XYZ affair to Congress in the spring of 1798,[8] and then, on July 7, Adams rescinded all treaties between the U.S. and France.[9]

In a July 16 letter to his Secretary of War Henry Knox, Washington wrote, “little did I imagine, when I retired from the theatre of public life, that it was probable or even possible, that any event would arise in my day, that could induce me to entertain for a moment an idea of relinquishing the tranquil walks and refreshing shades, with which I am surrounded.”[10]

At 66, Washington was decidedly not young for his time. In August 1798, Washington had a fever for two days, and a doctor was called to Mount Vernon. Washington recovered a few days later, but on September 3, he wrote, “I have been in a convalescent state, but too much debilitated to be permitted to attend to much business.”[11]

Washington wrote this in a letter to Secretary of State James McHenry as part of their correspondence about selecting some officers for the army. Washington didn’t seem to know where things stood, or what his role was in the process was. He asked McHenry to keep him informed “if any change should take place in settling the relative Rank of the Majr.-Generals.”[12]

A few weeks later, Washington found out that Adams had appointed Henry Knox to be Washington’s second in command, but Washington wanted his Revolutionary War aide and first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to be his second-in-command.[13] Washington wrote Adams a lengthy letter at the end of September to explain his displeasure at the move,[14] and after a month, Hamilton was appointed to the position.[15]

That winter, Washington, Hamilton, and Charles Pinckney[16] met in Philadelphia “for the purpose of making some military arrangements with the Secretary of War, respecting the force which is about to be raised.”[17]

To put it simply, Washington did not enjoy his time in Philadelphia. “The two Major Generals and myself were called to Philadelphia in November last, and there detained five weeks (very inconveniently to all of us) at an inclement season, in wading through volumes of applications & recommendations to Military Appointments,”[18] he wrote in a letter to McHenry.

Washington also lamented the fact that “I find by the Gazettes (I have no other information of these matters)” when it came to news about military appointments. In his letter, Washington told McHenry that he should “consider the letter as a private one.”[19]

In a January 1799 letter to his friend Bryan Fairfax, Washington apologized for the delay in returning Fairfax’s letter because of his trip to Philadelphia. Washington gave Fairfax some updates about his work as Commander-in-Chief, but he also took time in the letter to talk about his wheat and corn crops and the most recent harvest at Mount Vernon.[20]

The next week, Washington’s attention was once again pulled from life at Mount Vernon to a more mundane task of leading an army: the uniforms. He wrote a letter to his tailor in Philadelphia, James McAlpin, with requests for his uniform.

“On reconsidering the uniform for the Commander-in-Chief, it has become a matter of doubt with me, (although, as it respects myself personally, I was against all embroidery,) whether embroidery on the Cape, Cuffs, and Pockets of the Coat, and none on the buff waistcoat, would not have a disjointed and awkward appearance. … I should not prefer a heavy embroidery, or one containing much work. A light and neat one would in my opinion be more elegant and more desirable, as well for the Coat as the Waistcoat, if the latter is to receive any.”[21]

Washington also asked McAlpin about including an eagle as a part of his uniform.

“The eagle, too, having become part of the American cockade; have any of them been brought into use yet? My idea of the size is, that it ought not to be larger than would cover a quarter of a dollar at most, and should be represented (for the officers) as clothed with feathers. This any ingenious silversmith can execute; and, if four were sent to me, I would thank you, and would remit the cost as soon as known to me.”[22]

“In short, his military duties in 1799 demanded a fair amount of his time but commanded relatively little of his interest,”[23] said W.W. Abbott, Editor Emeritus of the Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia.

In his original letter to Adams where he accepted the position, Washington declined payment for his work.[24] When McHenry offered Washington two months’ worth of payment in September 1799, Washington wrote that he did not need the money and said, “I am resolved to draw nothing from the Public but reimbursements of actual expenditures; unless being called into the Field I shall be entitled to full pay and the Emoluments of office.”[25]

Washington would never see a battle as Commander-in-Chief this time. He died at Mount Vernon on December 14, 1799 as a three-star general. In 1976, President Gerald Ford “posthumously appointed George Washington General of the Armies of the United States and specified that he would rank first among all officers of the Army, past and present.”[26]

Footnotes

- ^ “Ask Mount Vernon,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/the-estate-gardens/ask/question/how-big-in-….

- ^ W.W. Abbot, “George Washington in Retirement,” Washington Papers, December 5, 1999, https://washingtonpapers.org/resources/articles/george-washington-in-re….

- ^ George Washington. George Washington Papers, Series 8, Miscellaneous Papers -99, Subseries 8B, Military Commissions, Honorary Degrees, Memberships, and Certificates of Appreciation, 1775 to 1798: Military Commissions, Honorary Degrees, Memberships, and Certificates, 1775 to 1798. /1798, 1775. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw8b00001/.

- ^ George Washington to John Adams, Letter, July 4, 1798.

- ^ George Washington to John Adams, Letter, July 13, 1798.

- ^ W.W. Abbot, “George Washington in Retirement,” Washington Papers

- ^ George Washington to John Adams, Letter, July 13, 1798.

- ^ Randal Rust, “XYZ Affair,” American History Central, December 2, 2020, https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/xyz-affair/.

- ^ “An Act to Declare the Treaties Heretofore Concluded with France, No Longer Obligatory on the United States.,” United States Statutes at Large 1 Stat. 578 § (1798), https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/qw03.asp.

- ^ George Washington to Henry Knox, Letter, July 16, 1798.

- ^ George Washington to James McHenry, Letter, September 3, 1798.

- ^ George Washington to James McHenry, Letter, September 3, 1798.

- ^ W.W. Abbot, “George Washington in Retirement,” Washington Papers

- ^ George Washington to John Adams, Letter, September 25, 1798.

- ^ George Washington to Timothy Pickering, Letter, October 26, 1798.

- ^ W.W. Abbot, “George Washington in Retirement,” Washington Papers

- ^ George Washington to William Vans Murray, Letter, December 26, 1798.

- ^ “Founders Online: From George Washington to James McHenry, 25 March 1799,” founders.archives.gov, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0334.

- ^ “Founders Online: From George Washington to James McHenry, 25 March 1799”

- ^ George Washington to Bryan, Lord Fairfax, Letter, January 20, 1799.

- ^ George Washington to James McAlpin, Letter, January 27, 1799.

- ^ George Washington to James McAlpin, Letter, January 27, 1799.

- ^ W.W. Abbot, “George Washington in Retirement,” Washington Papers, December 5, 1999

- ^ George Washington to John Adams, Letter, July 13, 1798.

- ^ George Washington to James McHenry, Letter, September 14, 1799.

- ^ “Frequently Asked Questions - Five-Star Generals,” history.army.mil, December 12, 2019, https://history.army.mil/html/faq/5star.html.

![Newspaper advertisement for Ona Judge, runaway slave [Source: Encyclopedia Virginia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2024-05/Ona%20Judge%20-%20Runaway%20Ad.jpg?h=10a38b52&itok=0_-DEpCm)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)