DC’s Most Underrated History Philanthropist

In a city full of millions of people and a myriad of activities to take part in, a twenty-five-year-old Albert Small roamed the concrete jungle that was New York City in 1949.[1] He was a bit bored without his beloved girlfriend, Shirley, by his side. Forced to occupy his time while Shirley worked her Saturday retail job to pay for school.[2] Albert was left to his own devices.[3] He was more used to the slower pace of his home in Washington, DC. The hustle and bustle of the people, noise, and sights of one of the world’s largest metropolises overwhelmed him at points. On this particular Saturday, Albert ducked into an antique bookstore as a means to escape the sensory overload that is the Big Apple.

Not all that interested in the old and dusty books which adorned the innumerable shelves of this establishment, Albert mindlessly perused the titles on the worn and cracked spines, none of which caught his fancy.[4] He peaked down at his watch, calculating the time until he could meet Shirley at work, and they could do something fun like go to a movie or out dancing. Realizing he still had hours before his Saturday actually got interesting, Albert resigned himself to a few more hours of listless wandering through the city.

Just as he braced himself to venture back out into the busy Manhattan streets, a tattered volume peered out to him from the sky-high stacks: the journal of Fred E. Woodward.[5] Something told him to stop and pick up the weathered-looking book. As Albert flipped open to the first page, he immediately noticed that the handwriting which made up the text of the work was a little strange. The volume was not just a journal but a diary. Continuing to flip through the pages, scanning the time faded scroll, Albert took note of the content; rather than the author discussing their daily life and struggles, Woodward had meticulously detailed the state and location of the District of Columbia’s boundary stones. Black and white photographs accompanied each description.[6] As a born and raised Washingtonian, Albert recognized these markers as the approximately one hundred sandstone landmarks which outlined the original borders of the federal city from when Pierre L’Enfant designed the Capital back in the late eighteenth century.[7]

Fascinated by the words and images recorded by Woodward in 1905, Small brought the journal to the clerk and purchased it.” From that point on” said Jackie Streker, the Curator of the Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection at the George Washington University Museum, “he caught the collecting bug and as anyone who knows a collector can attest, there is no getting rid of it.”[8] As an older Albert stated, “I guess I’m old fashioned in that way. I like to go to the bookshelf and get a book in my hand and look at it and be able to show it to somebody—something I don’t feel I can do with a CD-ROM or a DVD.”[9] That one book picked off of the shelf that fateful Saturday in 1949 set Albert H. Small on a lifelong passion for his home city of Washington, DC and the many artifacts integral to its founding and illustrious history as this nation’s capital. Fortunately for future generations of students, scholars, and the general public alike, Mr. Small had the means, passion, and resources to build his hobby into a full-fledged collection.

Born October 15, 1925, at Columbia Hospital for Women, Albert grew up in the DC neighborhood of Chevy Chase and attended Woodrow Wilson High School.[10] He left the District to obtain a degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Virginia.[11] During his time at UVA, Albert felt the overwhelming urge to do his part for the nation and join the Second World War. He participated in an Officer's training program at UVA, where he was later commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the United States Navy.[12] After returning home from the war, Small finished his degree and graduated in 1946.[13] His love for learning seemed to know no bounds as he attended George Washington University Law School from 1948 to 1949 as well as worked towards his Master of Business Administration at American University.[14]

Coming from a long line of self-made men, it is no surprise that a young Albert set out on his own to make his mark on the world. Small's grandfather, Isadore, owned and operated a hardware store at 615 7th ST NW.[15] Small's father, Albert Sr., started his working life at his father's hardware store but chose to go into real estate financing, where he made a comfortable living for his wife, son, and daughter.[16] In 1930, Albert Sr.’s office was located at 1401 K ST NW.[17] When it came time for Albert to embark on his own career, he melded the influences of his grandfather's hardware background and his father's career in real estate to start his own real estate development company, the Southern Engineering Corporation.[18]

For most of his career, Small's company sought to fill a wide gap in the housing market. Following World War II and the passage of the GI Bill, returning veterans had access to affordable home mortgages. Still, there was not nearly enough supply of homes to satisfy the demand.[19] This was where the Southern Engineering Corporation came in for the Mid-Atlantic region. From Baltimore down to Norfolk, Small and his business built award-winning housing complexes ranging from apartments to townhouse communities.[20] Focusing a great deal of his projects in and around his home in DC, Albert- perhaps more so than any other person - shaped the way the city looks today, from the commercial spaces of downtown to the Parc Somerset Condominiums in Chevy Chase, Maryland.[21]

But Mr. Small's impact on DC extends much further than that of the city's physical landscape: he was one of the most prolific philanthropists of DC culture and history that the District has ever seen. His long list of accolades is proof enough of this fact. He has been awarded both the Presidential Medal and an honorary doctorate from GW, "the Woodrow Wilson Award for Corporate Citizenship from The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars of the Smithsonian Institution in 2007, the National Humanities Medal from President Obama in 2009, and was recognized by the Library of Congress, the National Archives and many other organizations for his dedication to history, education, and preservation."[22] In addition, he served on numerous philanthropic boards ranging from the National Archives Foundation to the National Symphony Orchestra.[23]

Small staunchly believed that his physical artifacts like books, maps, manuscripts, engravings, and so on were critical to how we understand the societies and places we live in today.[24] "He loved his city and its development," says Jackie Streker.[25] His passion for his collection was evident through the care and time spent researching new pieces he wished to buy.[26]

By the early 1990s, Albert grew his hobby into a full-on collection with some 200 pieces from the founding of the District in the early 1790s up until the early twentieth century.[27] This period is also known as the "Long nineteenth century."[28] In 1992, Small made the critical decision to hire local DC historian, James M. Goode, to grow and simultaneously round out his collection.[29] Goode acquired new pieces for Small that told a complete story of Washington, DC.[30]

In discussing the pair’s collecting strategy, Goode commented “if it’s rare, we want rare things.”[31] And indeed, they most certainly achieved “rare.” Items such as a signed letter from George Washington, an original copy of the Declaration of Independence, and a seemingly endless catalog of original maps and charts from key historical DMV events added depth and character to his collection.[32]

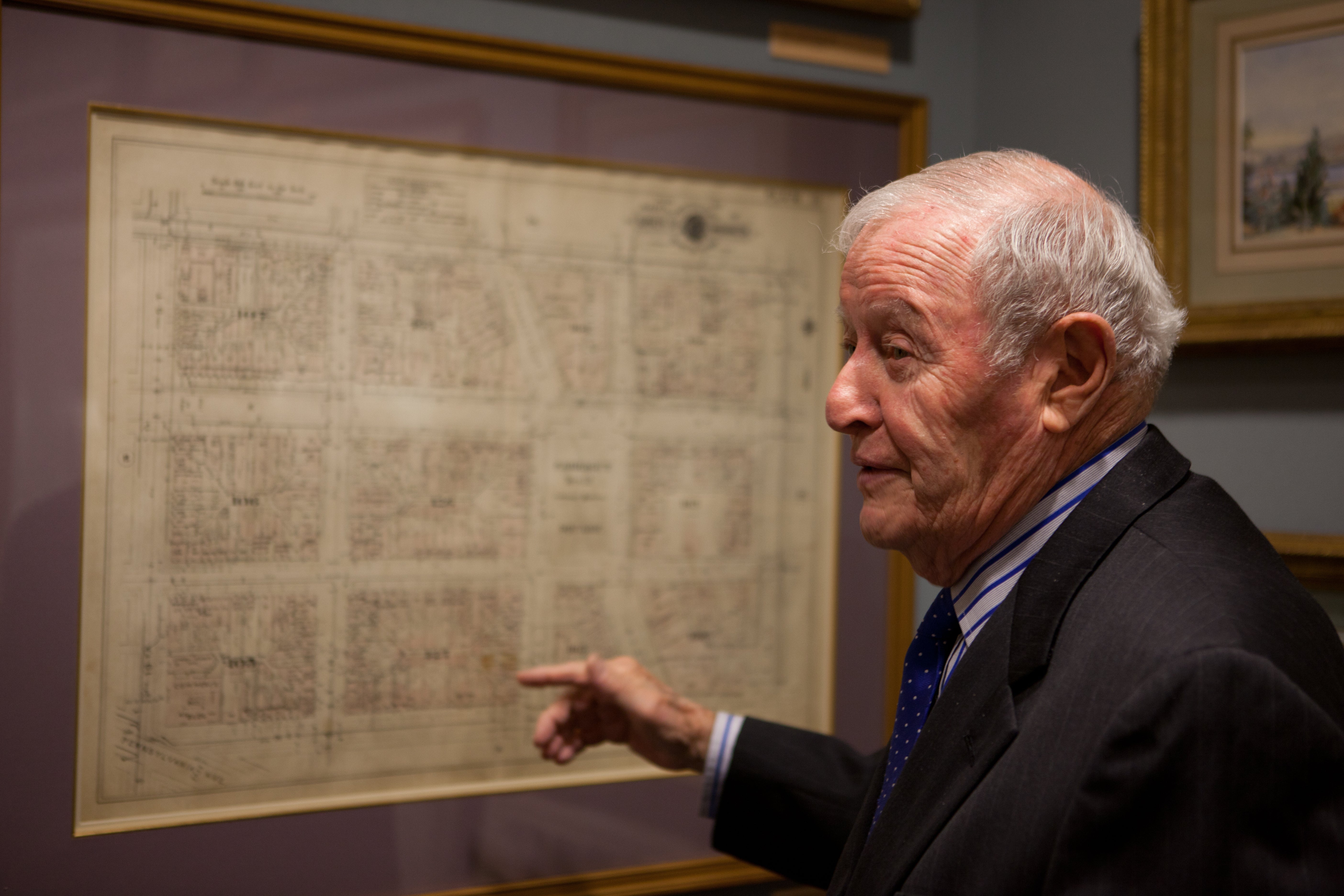

It was the maps and charts which Streker feels Mr. Small had the greater connection to: “His dad started as a developer, and then he got into it as well, which is why we have so many maps. Almost a third of our collection are maps. And I think that really spoke to him as a real estate guy to see where the city was growing and what was building out of it. And to see its growth. He really loved showing off his collection.”[33] As Goode noted in regard to Small’s maps, “it’s probably the best map collection outside the Library of Congress.”[34] Considering all the other institutions and private collectors of such maps, coming up second only to the Library of Congress was a significant feat.

His lifelong passion was missing an essential part: sharing what he had amassed over the course of his life with the public. So, in 2004, Small donated collections and eventually the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library to his Alma mater, UVA, all about the founding of the nation. His vast toy car collection was donated to the Smithsonian Institution.[35]

However, his crowning achievement was his gift to George Washington University: the Albert H. Small Center for National Capital Area Studies, which houses the Washingtoniana collection.[36] In 2011, Mr. Small made this generous donation along with some $5,000,000 to renovate the 176-year-old Woodhull house on GW's campus to display the collection and center as well as build an adjacent building for the university's pre-existing Textile Museum.[37] Even after GW gained ownership of the Washingtoniana collection, Albert continued to grow it until his death in October of 2021.[38]

Small's dream and passion for making DC's history accessible to the most significant number of people is embodied through his collection. Students from all across GW's colleges interact with the collection, not only by visiting it but also through engagement with the documents through various programs such as the current one, which encourages students to visit the reading room, pick a piece or a series of works from the collection, and write a blog post about their chosen item and its significance to DC's history.[39] The blogs are then published on the museum's website, further widening the population of those who interact with the collection by making the material accessible online to those who cannot make it out to see the museum in person.[40]

Although Mr. Small passed away in 2021 at the ripe age of ninety-five, his mark on this city is indelible. Whether through the thousands of homes he developed, his twin commissioned paintings of Washington, DC or one of his three endowments, Small's legacy will endure for years to come. If you have not done so, take a trip to the GW Museum and see Small's lifetime work. You, too, will understand why Mr. Small was such a big man in preserving DC history.

Author's note: Mr. Small's generosity and dedication to history personally touched my life three years ago. In 2011, Mr. Small started the Normandy Institute, a program that funds high school students and their teachers to take a class devoted to the Normandy campaign during World War II. The teacher-student pairs from across the nation meet in Washington, DC for a week before heading across the pond to France to conduct a Staff ride where they visit all the important sites of the campaign. The culmination of the class is the day spent in the Normandy American Cemetery on Omaha beach, where each student reads a eulogy of someone from their hometown who perished in the fighting and is interred there. GW offers an undergraduate version of this class. I applied for the course knowing the significance of such an experience. Unfortunately, the college class is not funded, and the price tag is a bit hefty. I wasn't sure how I would pay for the course, but due to a generous donation made by Mr. Small to the college class, I had the opportunity to take the most meaningful experience of my life, and I will never forget him for his unwavering kindness. Thank you, Mr. Small, and I hope you Rest in Peace.

Footnotes

- ^ Steve Moyer. “Albert H. Small: National Humanities Medal,” meh.gov, National Endowment for the Humanities, 2009,

- ^ John Kelly, “A Capital Collection at GWU Showcases Traces of Washington's Past,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), September 19, 2016.September 19, 2016.

- ^ John Lim, “ Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection,” doaks.org, Mapping Cultural Philanthropy, summer 2019, https://www.doaks.org/resources/cultural-philanthropy/albert-h-small-washingtoniana-collection.

- ^ Kelly, “A Capital Collection at GWU Showcases Traces of Washington's Past.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jackie Streker (Curator of the Washingtoniana Collection) in discussions with the author, May 25, 2022.

- ^ Ibid. Although we commonly refer to L’Enfant by his French name, Pierre, he signed all of his documents related to the design of the Washington, DC with the English version of his name, “Peter.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Moyer. “Albert H. Small: National Humanities Medal.”

- ^ Anne Dobberteen. “Albert H. Small, 1925-2021,” Washington History 34, no. 1 (2022), https://www.jstor.org/stable/48662459.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid. And “In Memoriam: Albert H. Small,” gwtoday.com, the George Washington University, October 6, 2021, https://gwtoday.gwu.edu/memoriam-albert-h-small.

- ^ Dobberteen. “Albert H. Small, 1925-2021.”

- ^ Moyer. “Albert H. Small: National Humanities Medal.”

- ^ “Isadore Smolensky in US City Directories 1822-1995; Washington, DC,” published in 1899, accessed through ancestory.com on June 2, 2022.

- ^ Dobberteen. “Albert H. Small, 1925-2021.”

- ^ “Albert Small in US City Directories 1822-1995; Washington, DC,” published in 1930, accessed through ancestory.com on June 2, 2022.

- ^ “Greenberg and Small building in Baltimore,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), July 30, 1966.

- ^ Daniel H. Street, “Albert Small Heads Bug Apartment Unit,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), May 18, 1968.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Dobberteen. “Albert H. Small, 1925-2021.”

- ^ In Memoriam: Albert H. Small,” gwtoday.com. And Maura Scanlon, “Remembering Albert H. Small,” capitaljewishmuseum.org, The Capitol Jewish Museum, October 4, 2021, https://capitaljewishmuseum.org/statement-on-albert-h-small/

- ^ Dobberteen. “Albert H. Small, 1925-2021.”

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kelly, “A Capital Collection at GWU Showcases Traces of Washington's Past.”

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kelly, “A Capital Collection at GWU Showcases Traces of Washington's Past.”

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Dobberteen. “Albert H. Small, 1925-2021.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)