Grant Us More Jazz on the Radio: How Felix Grant Brought Jazz to the D.C. Airwaves

Shock rippled through the steamy streets of Washington, DC, in early August 1979. The source of the buzz was not the result of back-to-back testing of nuclear weapons by the United States and the Soviet Union.[1] It was not even the sale of the nearby Baltimore Orioles to D.C. lawyer Edward Bennett Williams for the grand sum of $12.3 million.[2] The source of the city’s consternation involved the smooth timbre of a DMV staple – or the lack thereof. Felix Grant – one of Washington’s most beloved radio deejays for a generation – was being pulled from the airwaves.

For most DMV residents who started living in the area after 1993, the words “Album Sound” probably do not ring a bell. But ask any person who resided here between 1945 and the early 1990s the same question, and there’s a good chance the tinkling notes of the iconic theme song “Tenderly” will fill their minds, accompanied by Grant’s easy voice.[3]

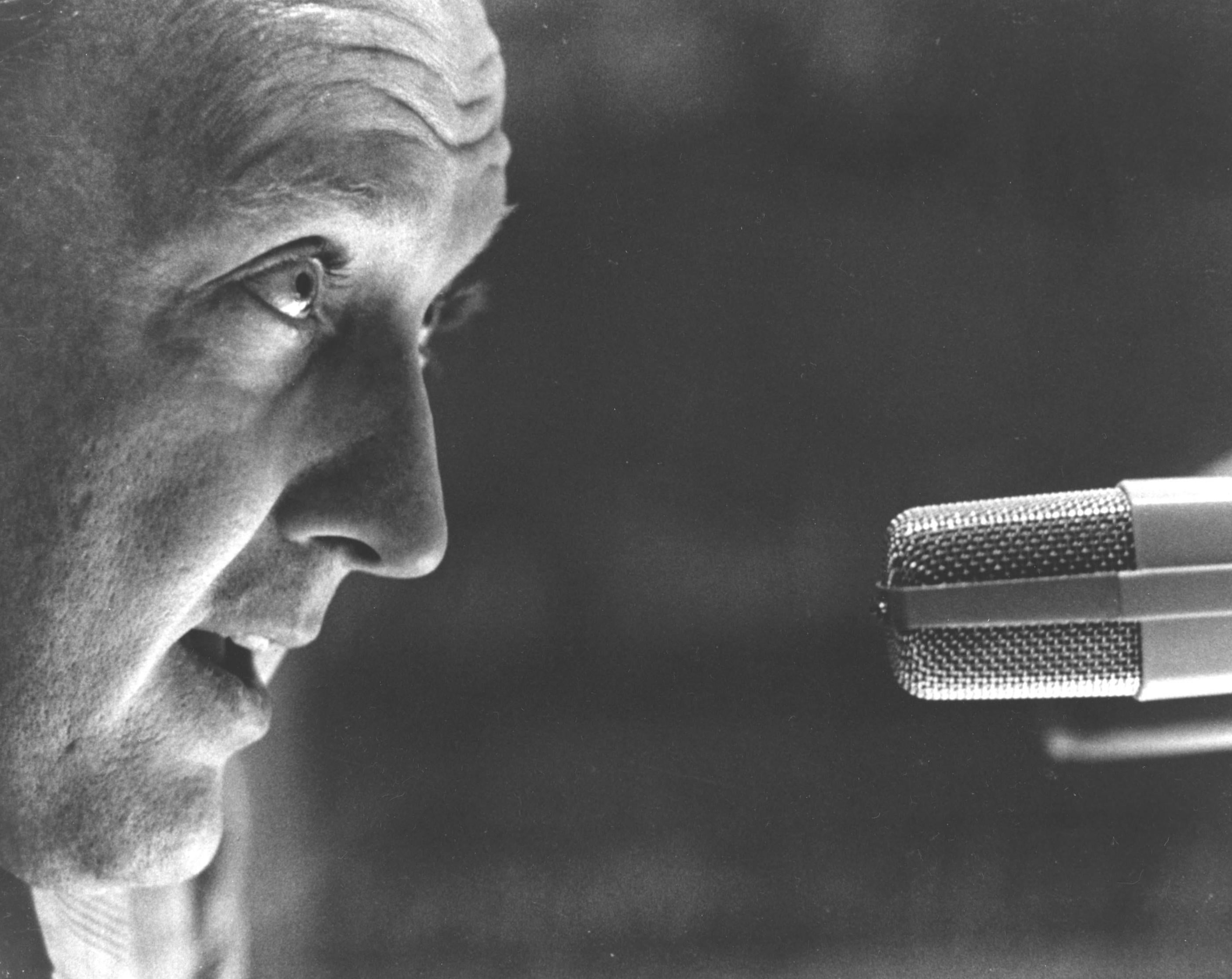

The son of Irish immigrants who moved to New York City at the turn of the twentieth century, Grant had been bitten by the radio bug early in life. As he recalled in a 1989 interview:

Somewhere along the line, I got this tremendous urge to listen to music on the radio. They used to broadcast from a speakeasy over at 97th and Amsterdam Avenue, and I remember lying there with my ear next to the radio— we’re talking about a kid maybe 9 or 10 years old— and trying to imagine how that music got from that speakeasy three blocks away into my radio in our apartment on 94th Street. All the guys I went to school with knew all the lineups of the Giants and the Yankees. ...I knew none of that, But I knew bands and music and songs. I had this radio thing right from the beginning.”[4]

Developing a love for jitterbugging, be-bopping, and the swinging sounds of jazz, was it for Felix.[5] He knew from the ripe age of ten that he wanted to be a part of the world of jazz when he grew up.

Grant made a name for himself in the Washington area radio scene after heroically serving in World War II as a distinguished Quartermaster in the Coast Guard.[6] He perfected his public speaking skills when the military sent him on a tour of war production factories, sharing his war stories of saving sailors on downed ships in the South Pacific and stressing the importance of the war stuffs manufactured at plants across the United States.[7]

Coming to Washington after the war, Grant started his career as an announcer for the station WWDC, slowly yet surely, figuring out his on-air personality.[8] More so than the white artists like Perry Como and Frank Sinatra, which WWDC featured during the daytime hours, the music of African American artists spoke the loudest to Grant.[9] While Washington had no African American-owned and operated radio stations in the post-World War II era, WWDC catered its nighttime broadcasts to a more African American demographic.[10] In 1945, Felix began announcing for WWDC during their nighttime slot, bringing the jazz played at the predominantly African American clubs on U Street to the broader DC public.

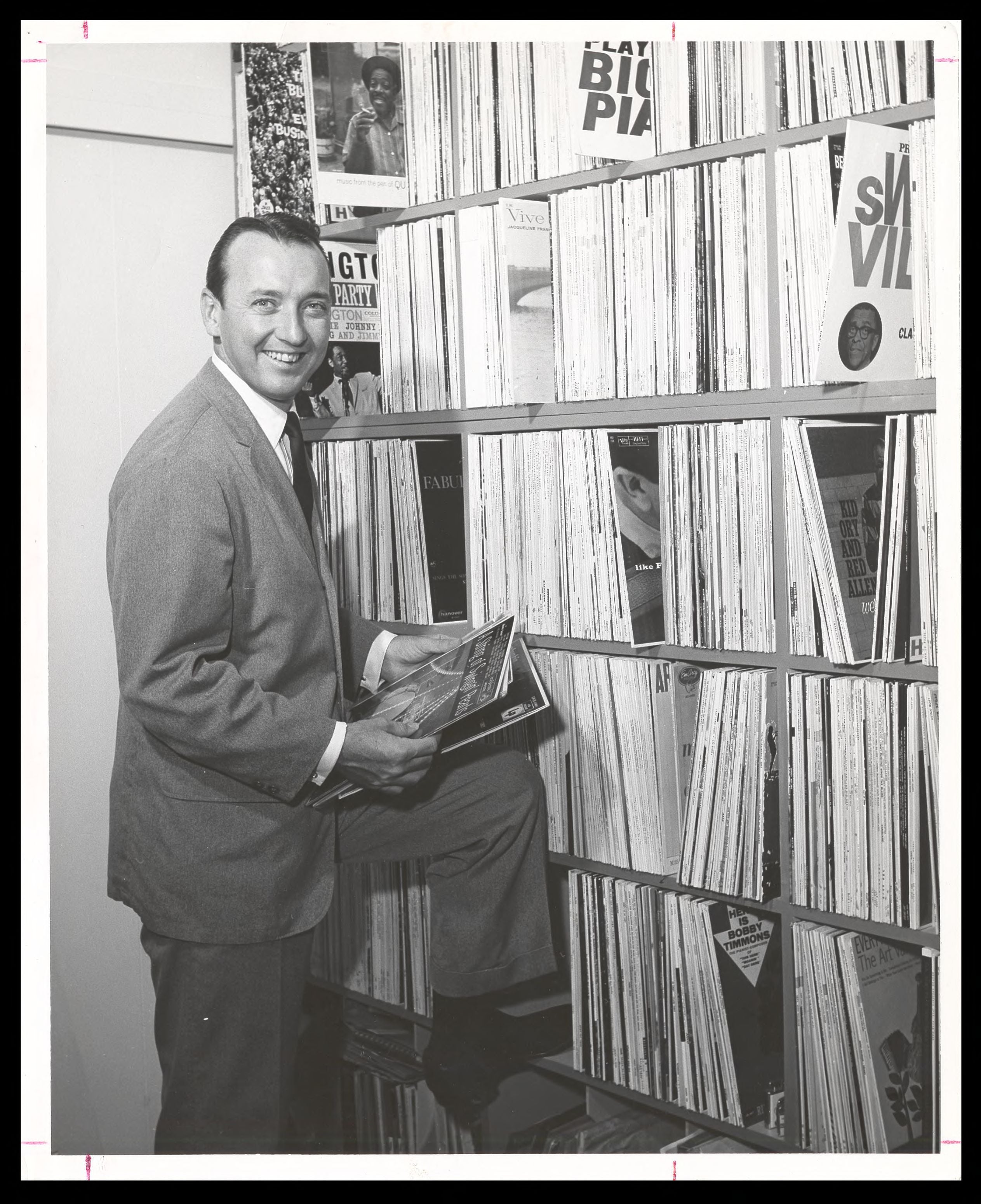

After seven and a half years with WWDC, Grant made the all-important decision to move to another local station, WMAL.[11] The choice was not easy. He took a fifty percent pay cut to work for WMAL, but the reward was sweet: Grant could program his eight to midnight show however he wanted and would face no input from the station managers.[12] Such a carte blanche served well for Felix’s style. Over the next three decades, he perfected a method for outlining his shows. This preparation involved three to five hours daily of intense research into different songs, artists, and groups, the meticulous organization of his playlists, all the while figuring out how to make the complicated language of jazz accessible to various listeners.[13]

The result of all his hard work and planning was the number one rated radio show by DC listeners on either FM or AM.[14] During the height of his career, some 180,000 different people in the DMV listened to Grant’s show every week and by the late 1970s, “Album Sound” was the longest continuously airing show of its kind in the nation.[15] Furthermore, as his efforts helped popularize both bossa nova and reggae to American audiences, international acclaim followed. Brazil awarded him the Order of the Southern Cross (the highest award given to a foreigner), and the University of Jamaica named its music library after him (the only American with a library outside of the United States named after them.)[16]

Beyond his prestigious accolades, Felix Grant’s show promoted racial equality in DC. Believing that music transcended the artificial barriers of race, Grant was one of the few white people who frequented the African American clubs on U Street during the age of segregation.[17] Bearing witness to the beauty of the historically African American medium of jazz was more critical to Grant than the laws that prescribed separate establishments for whites and blacks. He wanted the rest of the world to hear the music of African American jazz artists. He promoted black musicians on his show and refused to perpetuate racist stereotypes of African Americans while on air.[18]

Grant’s programming was widely beloved by DMV residents. Night after night, he crafted a unique show, free of judgment and full of his love for music. He introduced pieces in a matter of a fact manner, sharing facts about the artists and not delving too deep into the minutia, which can accompany discussions of jazz.[19] He did not rely on music charts like Billboard to tell him what to play. It all came from what he deemed to be good music.[20] With the ubiquity of radio during the middle part of the century and his long tenure riding the radio waves, Felix felt like family to a myriad of people throughout the greater Washington, DC area.

That is why what happened just a few weeks before Grant celebrated his twenty-fifth-anniversary broadcasting with WMAL dumbfounded so many Washingtonians. While Felix convalesced after a bout of laryngitis, executives at WMAL decided “Album Sound” was not suited for their AM radio station.[21] In the years preceding 1979, AM radio across the nation moved away from broadcasting music to focusing on sports talk and comedy shows.[22] As a result, the executives at WMAL saw it best for their ratings and overall bottom line to remove Grant from his Monday to Friday prime time spot and cut his airtime down to a few hours on the weekend.[23] His refined and cultured show was to be replaced by “veteran talker Johnny Holliday, an experienced entertainer who’ll make interviews, comedy, call-ins, and a little music” according to a Washington Post article that reported on the station’s plans.[24] Needless to say, the new eight to midnight broadcast on WMAL was not intended to be a cultural institution like “Album Sound.”

Grant was angry and hurt by the decision and the fact that he was not given the decency of a conversation or even a forewarning of what the station planned to do with him and “Album Sound.” Reflecting on the incident after the fact, he commented, “In all candor, the management of the station was never fond of what I did. It was a, I shouldn’t say a laughing stock, but it kind of was. He’s playing all that crazy stuff. And, they had no feeling for the music whatsoever, and therefore felt that it had no real value.”[25] That is where the executives at WMAL were wrong. Sure, the numbers for radio trends told them replacing Grant would grow their station and ultimately make them more money, but it is hard to determine the public’s opinion when numbers are the only metric used to make a decision.

Public outcry was swift and immediate when news broke about the reshuffle at WMAL. Both The Washington Post and The Evening Star ran multiple stories on the firing of Grant.[26] The Star even published the reactions of Washingtonians, of which the opinion seemed unanimous: outrage and disbelief that ratings were more important than a pillar of the local community.[27] For example, John D. Thornton of Arlington wrote:

I am indeed sorry to learn of the removal of Felix Grant’s nightly ‘Album Sound’ from WMAL. How can one possibly expect music-oriented listeners to stay tuned for one hour of sports trivia, followed by another on Politics, in a city already saturated with the same? WMAL admits that 67 percent of its listeners prefer music. If so, then why remove the very best? I have never seen an editorial so favorable to a radio announcer’s performance as yours. Calling him a Washington landmark is something I’ve never seen in my life. I am sorry, WMAL. You blew it. I would be surprised if you didn’t get a letter from the mayor, the city council and half the members of Congress.[28]

And the letters did come — over seven hundred of them— in addition to another two hundred phone calls.[29] Clearly, the outcry was large and loud. When it came down to it, the greater DC community, could not imagine their weekday nights without the background track of Felix Grant, and the outpouring of support for Grant saved his show.

After over three weeks of holding their ground, WMAL eventually conceded. The Post published a full-page picture and short article titled “The Great Felix Grant Goof or How WMAL Radio Listened to Its Listeners.”[30] At a press conference on August 22, WMAL apologized to Grant and the people of DC. The station manager sheepishly said, “You know I had the opportunity to make a huge mistake, and I’ve enjoyed every moment of it. . . Now mind you, this change was something that didn’t happen, I’d hate to be here if it had happened.” Editors at The Evening Star aptly titled their report on the announcement “WMAL Eats Crow and Finds it to their Liking, as the Station Decides to Keep Felix after all”.”[31]’

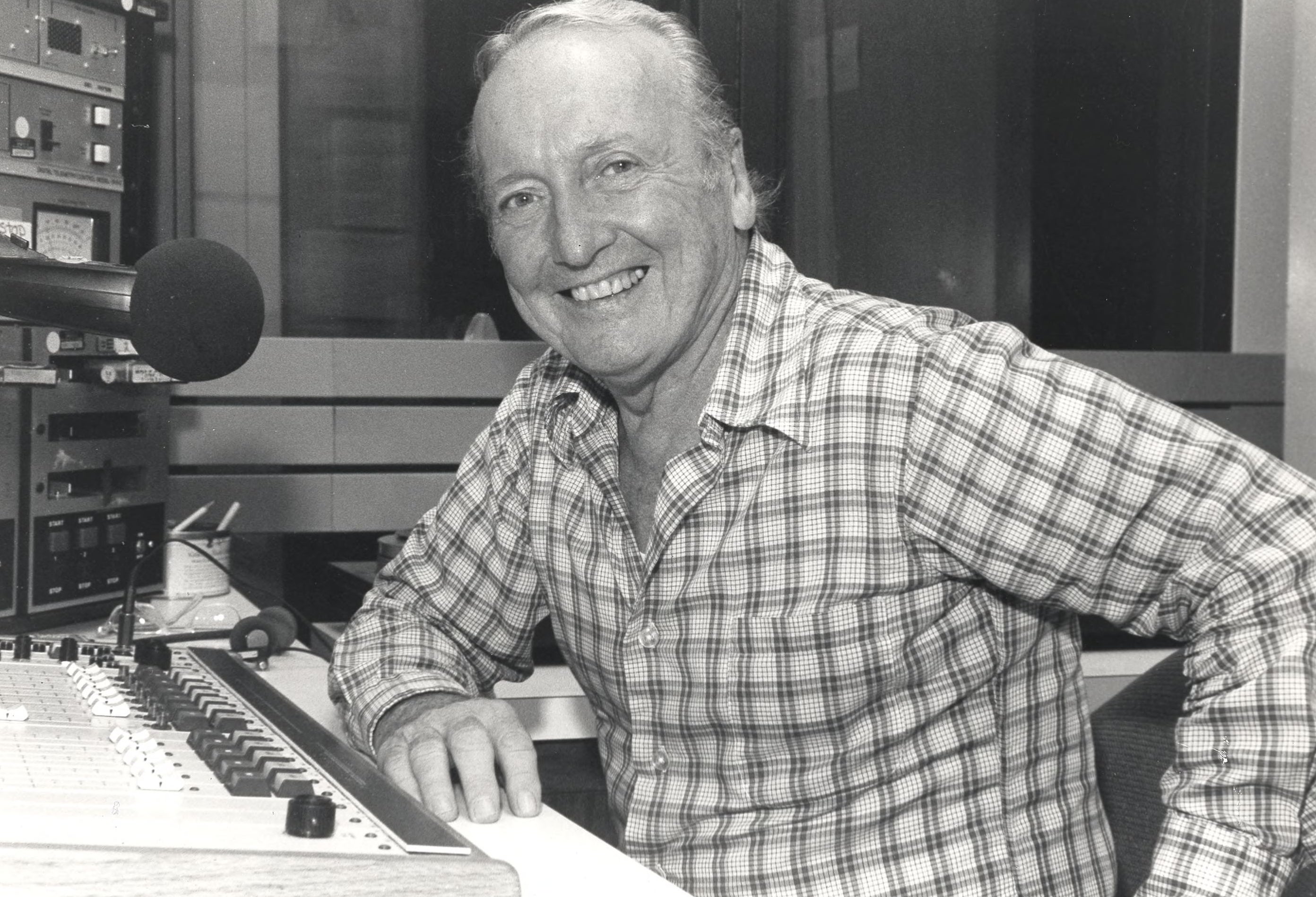

For an additional five years, Grant remained in his regular slot on WMAL. In 1984, however, WMAL again pulled Grant’s show, but this time not to another day/hour, but rather all together.[32] Unfortunately for Grant, the public paid little attention, and Grant was unceremoniously fired by WMAL.[33] Due to his name and reputation, he quickly found another spot broadcasting a new Jazz show for the station WRC.[34] Over the next nine years, Grant continued to bring his knowledge and the sounds of jazz to the DC area on a more infrequent basis.[35] The more limited schedule turned out to be a blessing in disguise for Grant, who fought vicious battle after battle with liver cancer.[36] On June 26, 1993, Felix Grant’s tender baritone was heard for the last time on his final radio station, WDCU. He passed away in October of the same year from cancer he fought so hard to stave off.[37]

Over a nearly fifty-year career of highs and lows bringing jazz to the people of the Beltway, Felix Grant created a legacy that should be remembered. Not only did he keep tens of thousands of people company on a nightly basis with “Album Sound,” he united people as diverse as cab drivers and congressmen with his love of music. His influence upon all walks of life is no better illustrated than the protest over the removal of his show in 1979. It is hard to think of a modern equivalent of a person who touches so many in the DC community today. If the legacy of Felix Grant leaves us with nothing else, let it be this: music has the power not only to entertain but also to unite and heal. Go and listen to a song that means something to you and let the memory of Felix Grant inspire you to love music, just like him.

Footnotes

- ^ “What Happened in August 1979,” onthisday.com, On This Day, accessed June 9, 2022, https://www.onthisday.com/date/1979/august.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Reuben Jackson (archivist at the University of the District of Columbia’s Felix E. Grant Jazz Archives) in discussion with the author June 7, 2022.

- ^ Ken Ringle, “Felix Grant: For the Love of Jazz,” Washington Post (Washington, DC), November 12, 1989.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Felix Grant interview with Bryant Dupre, tape #3 March 1, 1989, accessed through UDC Felix Grant Jazz Archives.

- ^ Ringle, “Felix Grant: For the Love of Jazz.”

- ^ Hollie West, “Felix Grant: He's the Top, He's the Dean of the Jazz DJs,” Washington Post (Washington, DC), November 20, 1977, accessed through UDC Felix Grant Jazz Archives.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ringle, “Felix Grant: For the Love of Jazz.”

- ^ West, “Felix Grant: He's the Top.”

- ^ Ringle, “Felix Grant: For the Love of Jazz.”

- ^ Roger Piantadosi, “Felix Grant: ‘It Was a Great Surprise,’” Washington Post (Washington, DC),August 5, 1979, accessed through UDC Felix Grant Jazz Archives.

- ^ West, “Felix Grant: He's the Top.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ken Ringle, “Appreciation: The Great Equalizer.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ West, “Felix Grant: He's the Top.”

- ^ Piantadosi, “Felix Grant: ‘It Was a Great Surprise,”’

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Listeners Score Victory For Jazz,” Radio Free Jazz, October 1979, accessed through UDC Felix Grant Jazz Archives.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Piantadosi, “Felix Grant: ‘It Was a Great Surprise,”’

- ^ “Felix-Renee Interview Transcript,”accessed through UDC Felix Grant Archives.

- ^ Piantadosi, “Felix Grant: ‘It Was a Great Surprise,”’And Dennis John Lewis, “Felix Grant: Radio’s Nighttime AM Jazz Fixture Falls to FM Stereo,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 1, 1979.

- ^ “Blues for Felix Grant,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 18, 1979.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Dennis John Lewis, “Listener Protest to WMAL Wins back Felix Grant Show.” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 22, 1979.

- ^ “Display ad 16: The Great Felix Grant Goof or How WMAL Radio Listened to Its Listeners,” Washington Post (Washington, DC), September 18, 1979.

- ^ Dennis John Lewis, “WMAL Eats Crow and Finds it to their Liking, as the Station Decides to Keep Felix after all,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 23, 1979.

- ^ Jeffrey York, “Felix Grant Fired,” Washington Post (Washington, DC), August 16, 1984, accessed through UDC Felix Grant Jazz Archives.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Chuck Conconi, “You Can't Keep a Good Man Down,” Washington Post (Washington, DC),September 12, 1984, accessed through UDC Felix Grant Jazz Archives.

- ^ Ken Ringle, “Appreciation: The Great Equalizer.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)