The Evolution of Arlington House: From Plantation to Military Camp and Freedperson Settlement, to National Cemetery

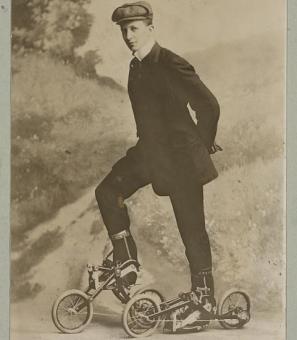

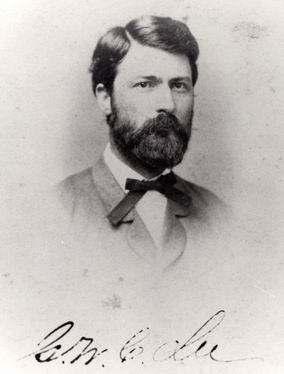

A few years after George Washington Custis Lee (known by most as “Custis”) graduated from the U.S. military academy in 1854,1 his grandfather – and namesake – George Washington Parke Custis died. Surely it was a mournful event, but it also meant something else significant: Arlington House, the place where young Custis had grown up, now belonged to his mother, Mary Custis Lee. As the new future heir, Custis was now one step closer to the 1,100-acre plantation and its enslaved workers belonging to him.

Since this is where his family derived its wealth, one might think this future prospect would have excited Custis. However, he did not seem to be particularly interested. In fact, he was so disinterested that he offered to give up his future claim to Arlington House the year after his mother Mary inherited it from her father.2

Perhaps being a young man trying to make a name for himself in the Army’s corps of engineers,3 the family wealth and legacy that resided in Arlington House did not hold enough weight for Custis. Or maybe he sought a life away from the house where he had lived all his life. Or it is possible that he simply believed that it would be there when he was older and ready for it.

What he likely did not foresee, however, were the dramatic changes that would come to Arlington during the Civil War.

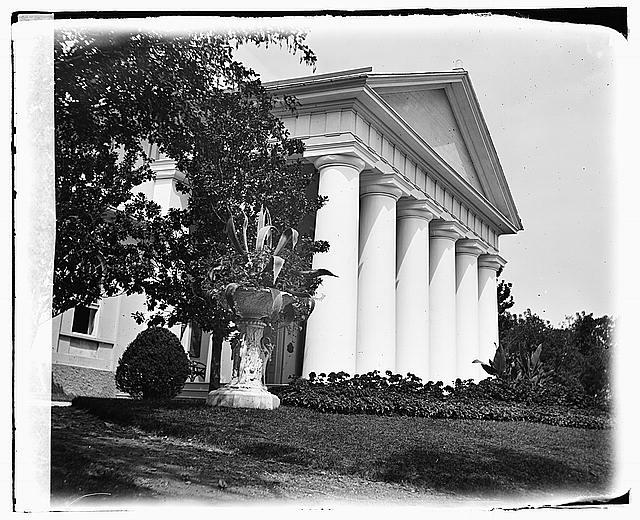

On April 20, 1861, Robert E. Lee officially resigned from the U.S. army and left for Richmond, where he would be appointed as a general in the Confederate Army.4 Mary Custis Lee did not leave until almost a month later, after having some family valuables packed up and sent ahead to her temporary home at Ravensworth near Annandale, Virginia.

She felt so certain that she would not be gone for long that she only packed up family valuables she deemed most important, leaving the rest behind.5 Just before she departed, she even left the house keys with her enslaved housekeeper Selina Gray, instructing her and the rest of the enslaved workers “to run the estate as though the Lees were to any day return.”6

As a preemptive move, in late May of 1861, the Union army crossed the Potomac and marched directly on to Arlington Estate in order to safeguard Washington, D.C. The estate, which sat in some forested hills with a clear view of Washington, D.C. was perfect for building fortifications against the enemy.7 This provided the Union army with a strategic advantage against the Confederates and any attempt they might make to strike the heart of the federal government.

As the war rolled on, Arlington was a busy place. The “New York Eighth … the Fire Zouaves, the Sixty-ninth, the Twelfth and Second of New-York City, the Twenty-fifth of Albany, First and Second of New-Jersey …”8 amongst other regiments made camp on the estate grounds, while “field and staff officers [occupied] the residence of Gen. Lee, of the rebel army …"9

In addition, a portion of the estate was transformed into Freedman’s Village, a community for thousands of former slaves who flocked to Washington after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The property had been selected by Lieutenant Colonel Elias M. Greene, chief quartermaster of the Department of Washington, and Danforth B. Nichols of the American Missionary Association and was intended to be a model community for freedpersons, many of whom were suffering under overcrowded conditions at camps in Washington.

As Greene wrote to Major General S. P. Heintzelman in 1863, the creators believed that the open air would improve the health of the freedmen and have other benefits: “There is the decided advantage afforded to them of the salutary effects of good pure country air and a return to their former healthy avocations as field hands under much happier auspices than heretofore which must prove beneficial to them and will tend to prevent the increase of disease now present among them.”10

Although Virginia was a Confederate state, because the Union Army occupied Arlington Estate, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation made it a place where freedpersons could go.11 Once within Union occupied territory, they would be protected from capture, which made the estate the closest choice for those who migrated to Washington.

Meanwhile, the Federal government was laying the groundwork for permanently seizing the property. In the summer of 1862, Congress established legislation allowing properties in Confederate regions to be appraised to collect taxes. The law served to both fundraise for the war, and, as historian Robert Poole observed, “punish turncoats like Lee.”12 Consequently, commissioners for Virginia assessed in September 1863 that based on Arlington Estate‘s 1860 market value of $34,100, the property accrued $92.07 in taxes13 which is approximately worth $2,781.33 in today’s money.14 When Mary sent a cousin to pay in her absence, the commissioners refused it as they required that payments be made by property owners in person. Because she was unable to cross enemy lines to do so,15 Arlington was put up for sale. And in 1864, the federal government made a bid of $26,800, laying claim to the land through a tax title.16

As the war raged on, the death toll mounted and the need for additional space to bury fallen Union soldiers became more pressing. As far as the Federal Government was concerned, Arlington was an ideal location for a new cemetery – for both logistical and symbolic reasons. It was close to Washington’s many war hospitals; the Federal government already had possession of it; and turning the former home of Confederate General Robert E. Lee into a burial ground from Union dead sent a powerful message.

Quartermaster Montgomery C. Meigs formally proposed Arlington as the site of the new cemetery in a letter to Secretary of War Stanton on June 15, 1864. The same day, Stanton approved Meigs’ recommendation and instructed that part of the Arlington Estate, “not exceeding two hundred acres” be surveyed and laid out for the national cemetery.17

The Republican press hailed the choice of Arlington. On June 17, the National Republican reported:

The ‘powers that be’ have been induced to appropriate two hundred acres, immediately around the house of General Lee, on Arlington Heights, for the burial of soldiers dying in the army hospitals of this city. The grounds are undulating, handsomely adorned, and in very respect admirably fitted for the sacred purpose to which they have been dedicated. The people of the entire nation will one day, not very far distant, heartily thank the initiators of this movement…. This and the contraband establishment there are righteous uses of the estate of the rebel General Lee, and will never dishonor the spot made venerable by the occupation of Washington.18

Over the coming months, Meigs gave soldiers under his command “specific instructions to make the burials near the mansion” and continued to push the issue. Though the soldiers working the mansion objected – likely uncomfortable at the prospect of residing so close to dozens of graves – Meigs’ wishes were eventually carried out.19 By August, 26 officers were buried at the northern end of the property (Section 27), which was within a few yards of the mansion.

Despite the changes at Arlington, Mary continued to anticipate the day that she would return to the estate to live, writing to a cousin that she “would never give up her claim to the estate.”20 True to her word, Mary made efforts to regain the title to Arlington in the years after the war.21 However, her proposition to Congress was not well received amongst Union sympathizers in the halls of the Capitol and the public.

One New York Times subscriber captured the sentiment in 1872:

Your paper lay beside me this morning, containing the letter from an “Advocate for Justice,” regarding the Arlington estate, when the widow of a Colonel of our Union army, killed at the head of his regiment, came for my weekly washing. Mine may be ‘woman’s logic,’ and wholly at fault, yet I could not but say, that till our Government was able to afford more than the pittance $30 a month to a Colonel’s widow and five orphan children, the time had not come for awarding constructive damages to rebel families.22

Even with the public outcry, soon after his mother died at the end of 1873, Custis picked up where she left off. Although he had been uninterested in the prospect of running the Arlington Estate as a younger man, his options had dwindled. Going back to the U.S. military was not possible, since he had chosen to side with the Confederates during the Civil War. And the Confederacy was now a thing of the past, so any future career he may have intended to create for himself in the new Confederate States of America was non-existent. Arlington Estate was quite literally the only potential option left that could bring him closer to the standard of living he had before the war. These factors no doubt came into play when he sought to work to regain the property.

By early 1875, he had petitioned Congress for a bill to “authorize G.W. Custis Lee to present his claim for compensation for the Arlington estate in the Court of Claims ...” However, the bill was postponed.23 In 1877 he sued the Federal Government for the return of the Arlington House property.”24 While Custis did aim to get the property back, The Evening Star reported “it is not the intention of the plaintiff to disturb the cemetery part of the estate if the suit should be decided in his favor. He is willing to sell that portion of the estate to the government at a fair price, to be determined by a board of arbitration.”25

Based on this news clipping, it seems that Custis did not simply want compensation for inheritance lost. He seemed to want to return to the home he once knew, barring the grounds that had been transformed in his absence.

The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which issued its ruling on December 4, 1882. In his official court opinion, Justice Miller stated that the government violated Custis’ “right to possession of his homestead. A right to recover that which has been taken from him by force and violence and detained by the strong hand.”26

Miller went on to note that the court could do no more regarding the case beyond its decision. He asserted that neither the president nor Congress had any right to seize the property without paying the owners. Miller further affirmed Custis’ case by saying, “it is absolutely prohibited, both to the executive and the legislative, to deprive any one of life, liberty or property without due process of law or to take private property without just compensation.”27

The vast change in Arlington House and the land surrounding it posed a problem for both Custis and the federal government after he won the lawsuit. The federal government, now that Arlington Estate was considered private property again, was faced with having to remove the thousands of bodies buried there during the Civil War and find some other place to re-bury them. And for Custis, not only were graves of the Union dead surrounding the house, but there was also an established community of newly freed African Americans – whose unpaid labor could no longer be used to further build and sustain his wealth – living on the property in what had become known as Freedman’s Village. Both needed to find a solution.

While it is unclear which of these factors sealed Custis’ decision, he made an offer to sell Arlington to the federal government a few months after the Supreme Court verdict.28 In March 1883, the government accepted his offer, and purchased the property for $150,00029 (over $4 million today).30 Perhaps after years of fighting in Congress and the courts, the mostly symbolic and financial victory was enough for Custis. Or perhaps he found the estate too far gone from what it once was and had expected to inherit decades before. Regardless of his hypothetical thoughts, Arlington Estate was forever transformed. It was soon to always and forever be most prominently known as the Arlington National Cemetery, and nothing – not even a legal battle through the ranks of the courts up to the judicial branch – could change that.

Footnotes

- 1

“Army Orders: III. Corps of Engineers.” Daily Evening Star. August 11, 1854. Accessed July 10, 2023.

- 2

“George Washington Custis Lee.” National Park Service. April 3, 2017. Accessed July 11, 2023.

- 3

“Army Orders: III. Corps of Engineers.” Daily Evening Star. August 11, 1854. Accessed July 10, 2023.

- 4

Chase, Enoch Aquila. “The Arlington Case. George Washington Custis Lee against the United States of America.” Virginia Law Review 15, no. 3 (January 1929): 209. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 5

Rose, Ruth Preston. “Mrs. General Lee’s Attempts to Regain Her Possessions After the Civil War.” Arlington Historical Society. 1978. 28. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 6

Poole, Robert M. ”How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be.” November 2009. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 7

Chase, Enoch Aquila. “The Arlington Case. George Washington Custis Lee against the United States of America.” Virginia Law Review 15, no. 3 (January 1929): 207. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 8

“From the New-York Eighth Regiment. Arlington Heights, VA., Head Quarters Eighth Regiment.” The New York Times. June 1, 1861. 1. Accessed July 24, 2023.

- 9 Ibid.

- 10 Letter, Col. Elias M. Green to Major Gen. S.P. Heintzelman, May 5, 1863. National Archives, RG 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, Records Relating to Functions: Cemeterial, 1829-1929. General Correspondence and Reports Relating to National and Post Cemeteries (“Cemetery File”), 1865-c.1914. Arlington, VA. Box 7, NM-81, Entry 576.

- 11

As the war neared its third year, President Abraham Lincoln released the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, to improve the Union’s chances of winning. Through this executive order, he was able to legally free enslaved African Americans escaping into Union territory from Confederate territories not under Union control. For more information, see: Lincoln, Abraham. “The Emancipation Proclamation.” National Archives. January 1, 1863. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- 12

Poole, Robert M. ”How Arlington National Cemetery Came to Be.” November 2009. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 13

”The Arlington Estate. The Suit to Oust the Government – History of Arlington – The Law of the Case – A Strong View.” The Baltimore Sun. June 2, 1877. 6. Accessed July 24, 2023.

- 14

Webster, Ian. ”CPI Inflation Calculator.” Official Data Foundation. Accessed July 19, 2023.

- 15

”The Arlington Estate. Decision of the United States Supreme Court – The Heirs of Mrs. General Lee Gain Their Inheritance.” The Baltimore Sun. December 5, 1882. Accessed July 24, 2023. 1.

- 16

”The Arlington Estate. The Suit to Oust the Government – History of Arlington – The Law of the Case – A Strong View.” The Baltimore Sun. June 2, 1877. 6. Accessed July 24, 2023.

- 17 Letter, Sec. Edwin M. Stanton to Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs, June 15, 1864. Copy in Arlington House archives. Original at National Archives, Records of the War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, National Cemeterial Files.

- 18 National Republican. June 17, 1864.

- 19 Memorandum, Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs, April 12, 1873. National Archives, RG 92: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, Records relating to functions: Cemeterial, 1829-1929. General correspondence and reports relating to national and post cemeteries (“Cemetery file”), 1865-c. 1914. Antietam, MD-Arlington, VA, Box 6, NM-81, Entry 576.

- 20

Rose, Ruth Preston. “Mrs. General Lee’s Attempts to Regain Her Possessions After the Civil War.” Arlington Historical Society. 1978. 28. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 21

”The Arlington Estate. The Suit to Oust the Government – History of Arlington – The Law of the Case – A Strong View.” The Baltimore Sun. June 2, 1877. 6. Accessed July 24, 2023.

- 22

”The Arlington Estate.” The New York Times. February 20, 1872. Accessed July 21, 2023. 2.

- 23

”Forty-Third Congress: Railroad Bills.” The Evening Star. February 8, 1875. Accessed July 11, 2023. 1.

- 24

Davis, Paul. “Washington‘s War Tent After the Civil War: A Family Affair.“ Museum of the American Revolution. February 2016. Accessed July 10, 2023.

- 25

”The Evening Star: Washington News and Gossip.” The Evening Star. March 6, 1878. Accessed July 10, 2023.

- 26

”The Arlington Estate. Decision of the United States Supreme Court – The Heirs of Mrs. General Lee Gain Their Inheritance.” The Baltimore Sun. December 5, 1882. Accessed July 24, 2023. 1.

- 27 Ibid.

- 28

”The Arlington Estate. Its Purchase Recommended by the Senate Committee.” The Washington Post. February 16, 1883. Accessed July 24, 2023. 1.

- 29

”Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial.” Arlington National Cemetery. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- 30

Webster, Ian. ”CPI Inflation Calculator.” Official Data Foundation. Accessed August 16, 2023.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)