The First Battle of Bull Run and Its Foolhardy Picnickers

When going out for a picnic, you might expect to enjoy good food, fun with friends, lovely nature and sunny weather. You probably don’t expect to end that picnic running for your life from an advancing army, hoping not to get captured or killed. But that’s just what happened to a group of picnickers one Sunday afternoon in 1861, just north of the city of Manassas. It was July 21st, the day of the first major battle of the American Civil War, or as it became known in the North, the First Battle of Bull Run. To tell the truth, those picnickers didn’t just become unlucky and happen to get in the way of the battle. They had actually chosen to go watch.

The Civil War is remembered as a long and bloody affair, but it’s easy to forget that just three months after it began, many Northerners believed the Union could quickly end the rebellion by capturing the new Confederate capital of Richmond. “On to Richmond!” many politicians and members of the Northern press cried, believing that the capital, just 100 miles south of Washington, could be taken in as little as 90 days. After all, thousands of Union volunteers were camped around Washington by May, ready to defend their city. It would be easy to just march them south and crush the Confederacy, right?1

This optimism, along with criticism from the Washington elite and press about his sluggishness, prompted President Abraham Lincoln to begin combat operations against the South with haste. On May 14, 1861, he appointed Brigadier General Irvin McDowell as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. McDowell began consolidating forces in and around Washington, about 35,000 men, which he organized into five divisions. It was the largest field army the continent had ever seen, but it wasn’t exactly battle-ready. Most of McDowell’s troops were just 90-day volunteers. While the volunteers were eager to answer their president’s rallying call and defend their capital, they were civilians, not soldiers. Most had no combat experience and lacked discipline. McDowell knew this.2 President Lincoln reassured McDowell, saying, “You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike.”3

On July 16th, McDowell left Washington to cheering crowds, and marched west with his 35,000-strong army. His objective was to seize the railroad at Manassas Junction, from where his army could move on to Richmond.4 But the Confederates were not sitting idle in Richmond. They were waiting for the Union at Manassas. Confederate General P. G. T. Beauregard commanded the Confederate Army of the Potomac, a 22,000-strong force. The Confederate troops and officers were as untrained and inexperienced as their Union enemies. The army camped in an eight-mile line along one side of a creek called Bull Run. Someone had tipped off Beauregard that the Union was coming. That someone was prominent Washington socialite Rose Greenhow, also a Southern sympathizer and Confederate spy. She passed coded messages about McDowell’s plans to Beauregard,5 who was headquartered in a farmhouse near Manassas. The farmhouse was owned by grocer Wilmer McLean, the owner of the house in Appomattox where Robert E. Lee would surrender almost four years later.6

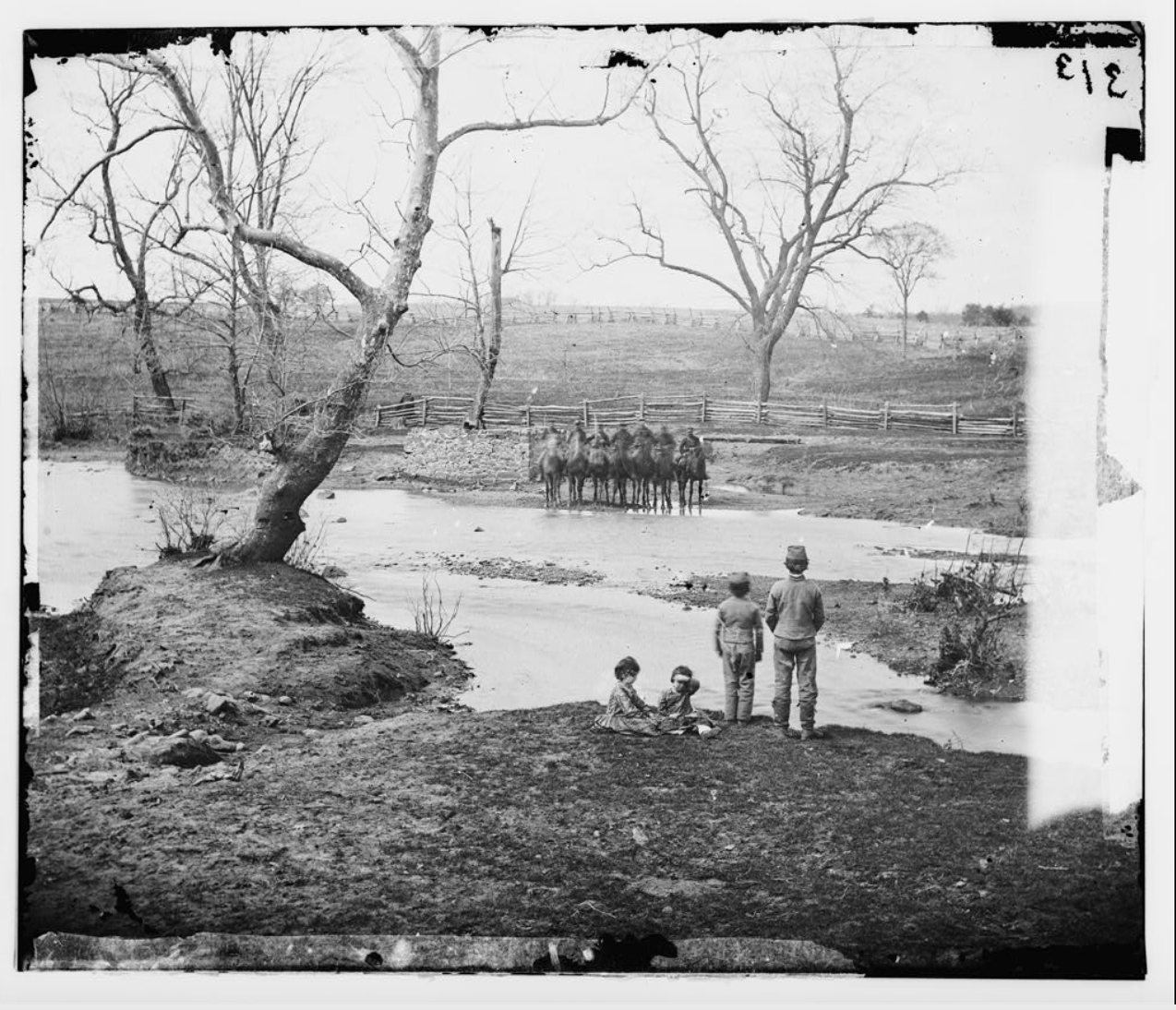

On July 21st, after a two-day march through the sweltering July heat, McDowell’s Union Army settled in Centreville, a town 25 miles from Washington. But the troops did not come alone. Hundreds of civilians rode from Washington, hoping to watch the coming battle. These Washingtonians went with the expectation of witnessing a short and triumphant end to the Southern rebellion.

Capt. John C. Tidball witnessed a “throng of sightseers” approaching down a road from Centreville. “They came in all manner of ways, some in stylish carriages, others in city hacks, and still others in buggies, on horseback and even on foot. Apparently everything in the shape of vehicles in and around Washington had been pressed into service for the occasion.” Some brought picnic baskets, opera glasses and bottles of champagne. The baskets of food may seem frivolous, but Centreville was a good seven-hour carriage ride away from Washington, and no Northerner could expect Southern hospitality from an enemy nation. Not wanting the little ones to miss out on the novelty of visiting a warzone, some parents even brought their kids!7 Why should they miss out on all the fun?

But it wasn’t just ordinary Washingtonians who showed up. “A Connecticut boy said, ‘There’s our senator!’ And some of our men recognized other members of Congress,” recalled Private James Tinkham of the 32nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry. Some of these men were the very same senators who called for the immediate invasion of the South. You might think the soldiers laughed at this crowd for their naivety, but sadly they didn’t have much more of an inkling of what war could be like. “We thought it wasn’t a bad idea to have the great men from Washington come out to see us thrash the Rebs,” said Private Tinkham.8

After days of reconnaissance, minor engagements and skirmishes, the battle was about to begin. On the morning of July 21st, Union infantry crossed Bull Run. The battle began in earnest at around 5:30 a.m., when Union artillery opened up on the Confederate’s left line. At first, it seemed to go off without a hitch. With charges and gunfire, the Union pushed the Confederates from position after position over fields and up the slopes of Henry Hill.9

Meanwhile, the spectators watched from five miles away on Centreville Heights. All they could see was gunsmoke rising above the treetops. They may have been disappointed by the lack of spectacle, if it weren’t for the good news filtering from the battlefield by Union officers. William Howard Russell from the London Times reported on the scene. “The spectators were all excited, and a lady with an opera glass who was near me was quite beside herself when an unusually heavy discharge roused the current of her blood - ‘That is splendid, Oh my! Is not that (sic) first rate? I guess we will be in Richmond to-morrow.’” An officer rode up from the battlefield, and was reported to have exclaimed, “We have whipped them on all points!”10 Union victory was assured…or so they thought.

Even though the Confederates were running, they were not out of the fight. Generals P. G. T Beauregard and Joseph Johnston restored order out of the chaotic retreat and reformed a new defensive position on Henry Hill, part of the Spring Hill Farm owned by the Henry family. A brigade of 2,500 Virginians and thirteen artillery pieces rolled into position atop Henry Hill, commanded by General Thomas J. Jackson. The fighting commenced on Henry Hill around noon.11 During the fighting, Confederate General Bernard Bee rallied his troops by shouting something to the effect of, “Look, there’s Jackson with his Virginians, standing there like a stone wall!” The exact words and meaning of this remark are debated because Bee was killed almost immediately after shouting them, and none of his officers left written reports about the battle. The only officer there to clear things up could have been Jackson’s chief of staff, Major Burnett Rhett. He claimed that Bee was calling Jackson out for failing to help his brigade when it came under heavy fire by the Union.12 Whatever Bee meant, the nickname stuck, along with its stoic, rather than inert, connotation.13

While the spectators were kept updated, most of the information was well over an hour old by the time it reached them. Emboldened by the good news of the Union’s initial success, and wanting a closer seat to the action, a group of senators joined William Russell as he rode closer, looking for a better vantage point. Around mid-afternoon, they found a group of reporters who gathered on a rise beyond a field hospital.14

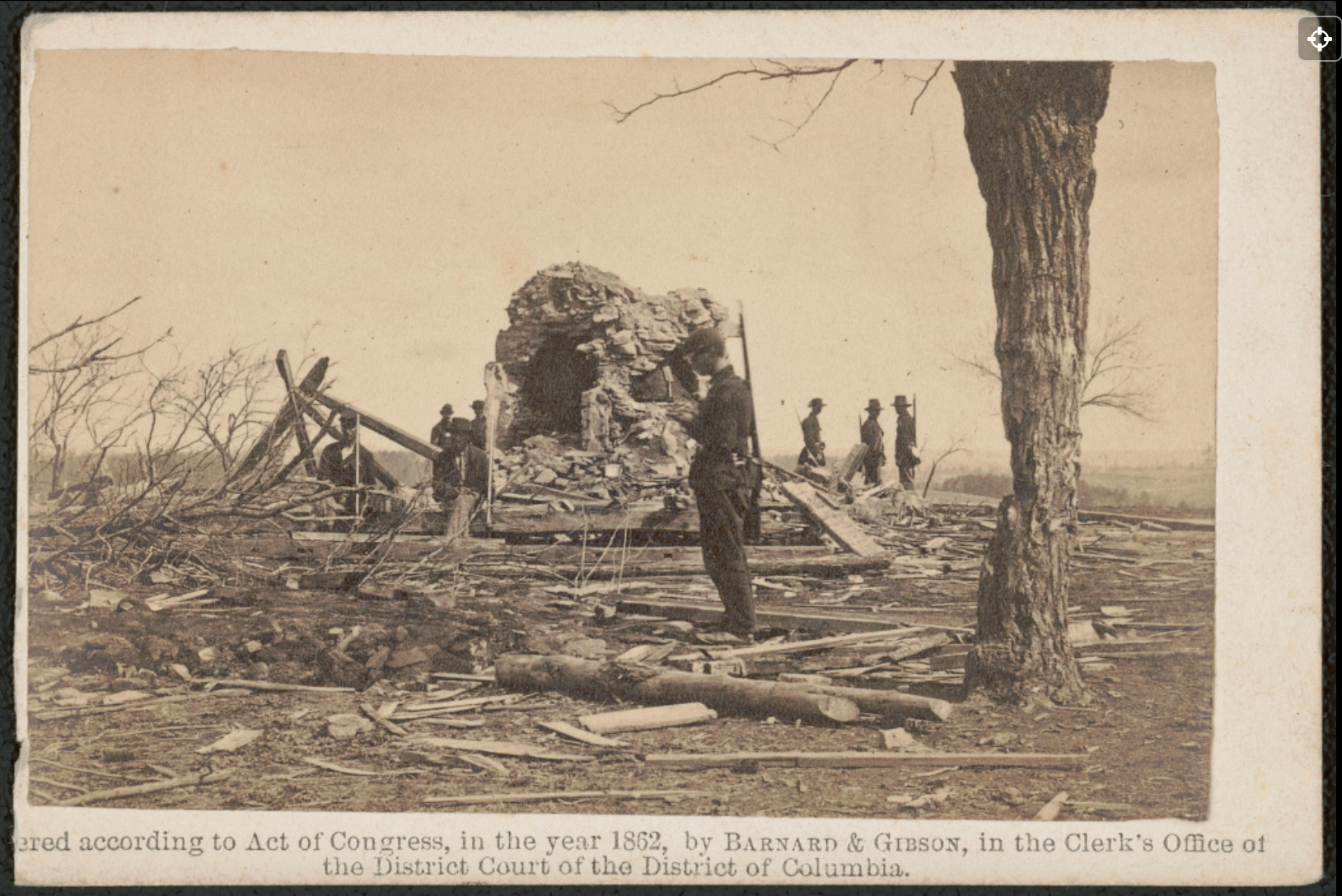

At 2:00 p.m., Union artillery fired at a little farmhouse on Henry Hill, where 84-year-old Judith Henry was lying bedridden. Cannon fire riddled the Henry House, killing her. Union infantry backed up the artillery and charged Jackson’s brigade. They fought across the hill. After switching hands several times, Jackson’s men captured the artillery. Now, the momentum was turning in the Confederates’ favor. Elsewhere, additional Union and Confederate brigades arrived on Chinn Ridge, where Union troops were exposed. Ditches filled with wounded men crawling on top of each other. Soldiers shouted, men groaned as they lay dying, and cannons fired. The battle was pandemonium. Confederate reinforcements were rolling in. At 4:00 p.m., Beauregard ordered a counterattack.15 Jackson admonished his men to “yell like furies,” and the Confederate “rebel yell” was born. Confederate reinforcements arrived, first by horseback and then by train. Thousands of Union troops began retreating across the entire battle line. The tide was turning.16

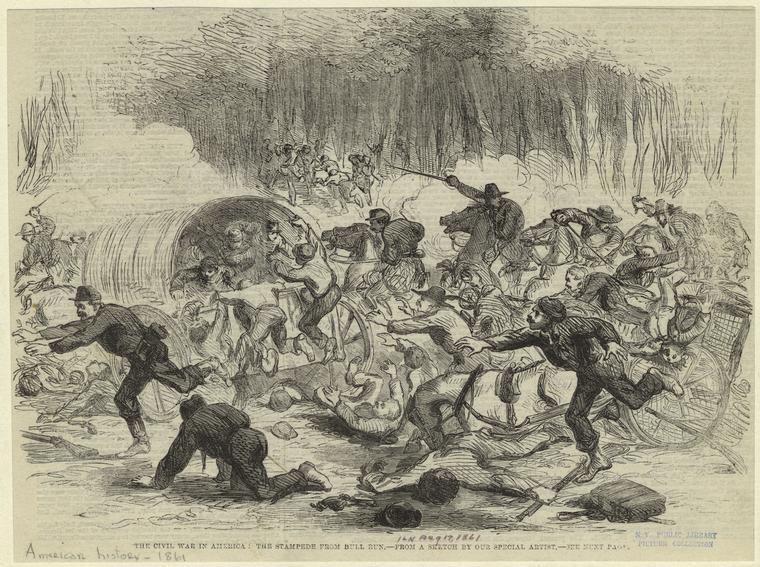

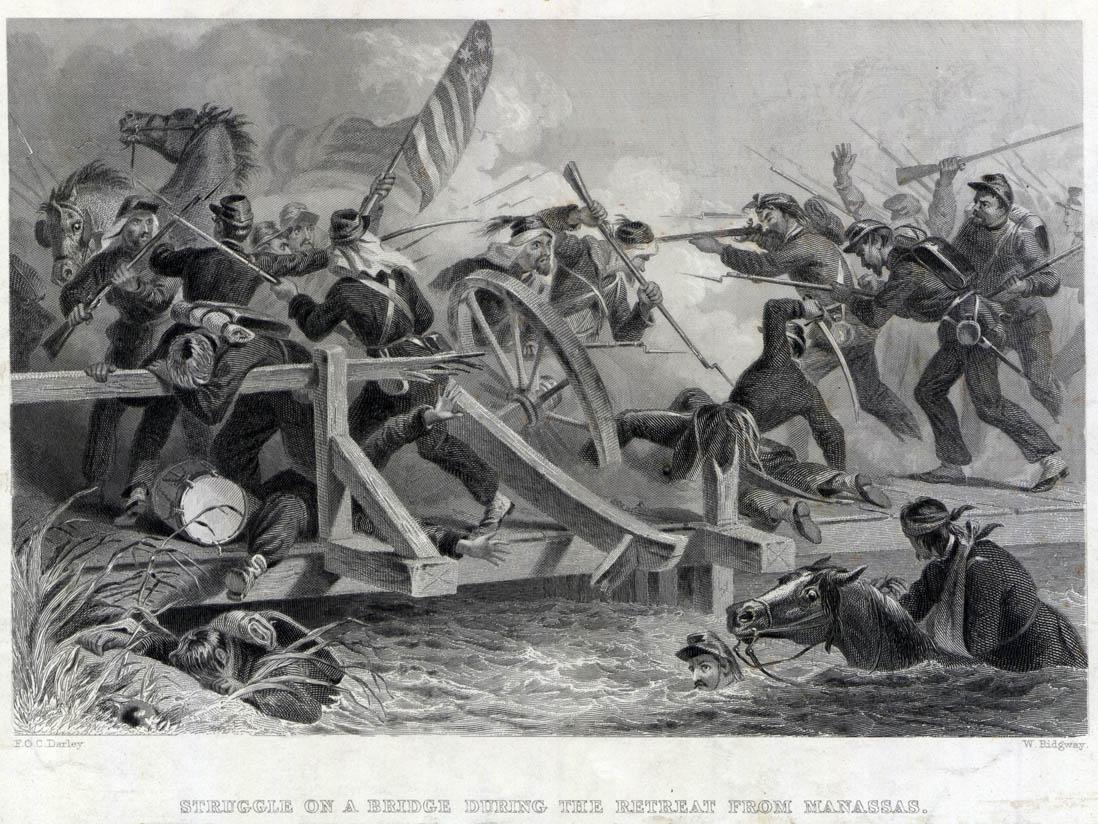

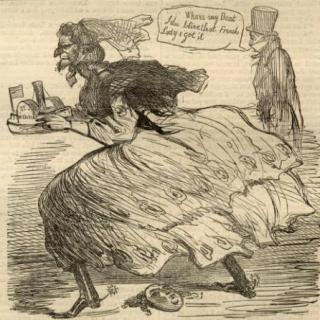

The retreat was orderly, at first. Regular soldiers shielded the fresher volunteers as they found the road back to Washington. But the road home was blocked by people, wagons, horses, and carriages. Just a short time prior to the soldiers’ arrival, picnickers were still eating their lunch and imagining the day the Union would march on Richmond. Now though, everyone was fleeing any way they could. Confederate artillery struck a Union wagon on a bridge, starting a fire. “Turn back! Turn back!” one Union soldier cried as he ran.

The senators who were present didn’t seem to appreciate the danger. Take Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan, who tried to block the road to stop the retreat. And Senator Ben Wade of Ohio, who picked up a rifle and threatened to shoot any soldier who ran. Congressman Washburne tried to rally the fleeing soldiers near Centreville. He was ignored. A Confederate shell destroyed the buggy carrying Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, while the future vice president was distributing sandwiches. He fled on a stray horse.

The Southern press called the humiliating retreat the “Great Skedaddle”. Remarkably, there were no reported deaths among the panic-stricken civilians. But not everyone got out. Congressman Ely from New York was captured by Confederate soldiers of the 8th South Carolina Infantry. Out of all the politicians shouting, “On to Richmond!”, Ely was the only one to get his wish. He spent the next five months languishing as a prisoner of war in Richmond. There were other close calls. Senator James Grimes of Iowa barely avoided capture. Thankfully, he may have learned his lesson, as he swore never to go near another battlefield again.17, 18

The civilians may have escaped with their lives, but the soldiers weren’t so lucky. An estimated 2,896 Union troops were killed, wounded, captured, or went missing at Bull Run. Although the Union casualties were appalling, they could have been much worse. The Confederates were too disorganized to press their advantage and pursue the Union troops much farther than Bull Run, probably sparing more lives. There were an estimated 1,982 Confederate casualties, for a combined total for the battle of 4,787 across the 60,680 forces that fought at Bull Run. President Jefferson Davis arrived from Richmond to bolster his forces, while Irvin McDowell limped back to D.C., arriving on July 22. He was later relieved of his command and replaced by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan.19

It is easy to forget that amidst all this chaos, spectators too were running for their lives. Which begs the question, what were they thinking by showing up in the first place? Clearly, they were overconfident in the Union’s ability to crush the Confederacy. To be fair, war tourism began as far back as at least 1653, when Dutch artist Willem van de Velde watched a naval battle between the Dutch and English from his little boat.20 Prince Menshikov of Russia invited a group of women to watch the Battle of Alma in Sevastopol during the Crimean War in 1854. By the mid-19th century, it wasn’t uncommon for civilians to watch a battle because so many took place close to population centers. The practice of watching battles ended after weapons became so destructive that it was virtually impossible for civilians to have any confidence that they would be safe close by.21

The First Battle of Bull Run (or Battle of First Manassas as it became known in the South) was a rude awakening for those expecting a short and easy war, and a sobering reminder of the long and bloody slog that is so often the reality of war. As a result of the battle, 90-day volunteer service was abolished. Congress expanded the Union Army and reorganized it for the arduous road ahead.22

Footnotes

- 1 Rafuse, Ethan Sepp. A Single Grand Victory: The First Campaign and Battle of Manassas. American Crisis 7. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002.

- 2

Lewis, Justin. “First Battle of Bull Run.” Cathedral of Liberty - Preserving American Heritage & History (blog), August 12, 2020.

- 3

Mr. Lincoln’s White House. “The Generals and Admirals: Irvin McDowell (1818-1885).” Accessed April 19, 2024.

- 4

Fry, James B. “The Number of Men Engaged at (First) Bull Run.” The Century Magazine, October 1, 1884. WayBack Machine.

- 5

Lewis, Justin. “First Battle of Bull Run.” Cathedral of Liberty - Preserving American Heritage & History (blog), August 12, 2020.

- 6 The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns. Miniseries, Documentary. PBS, 1990.

- 7

Burgess, Jim. “Spectators Witness History at Manassas.” American Battlefield Trust, March 10, 2011.

- 8 The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns. Miniseries, Documentary. PBS, 1990.

- 9

National Park Service - Manassas National Battlefield Park, Virginia. “The Battle of First Manassas (First Bull Run),” September 4, 2023.

- 10

Burgess, Jim. “Spectators Witness History at Manassas.” American Battlefield Trust, March 10, 2011.

- 11

National Park Service - Manassas National Battlefield Park, Virginia. “The Battle of First Manassas (First Bull Run),” September 4, 2023.

- 12

Lewis, Justin. “First Battle of Bull Run.” Cathedral of Liberty - Preserving American Heritage & History (blog), August 12, 2020.

- 13 Olsen, Christopher J. The American Civil War: A Hands-On History, 2007.

- 14

Burgess, Jim. “Spectators Witness History at Manassas.” American Battlefield Trust, March 10, 2011.

- 15

National Park Service - Manassas National Battlefield Park, Virginia. “The Battle of First Manassas (First Bull Run),” September 4, 2023.

- 16 The Civil War: A Film by Ken Burns. Miniseries, Documentary. PBS, 1990.

- 17

United States Senate. “Senators Witness the First Battle of Bull Run.” Government. Accessed April 22, 2024.

- 18

Browne, Patrick. “Bull Run and the Art of the Skedaddle.” Historical Digression (blog), July 28 20211.

- 19

American Battlefield Trust. “Bull Run.” Accessed April 22, 2024.

- 20 Butler, Richard, and Wantanee Suntikul. Tourism and War: Contemporary Geographies of Leisure, Tourism and Mobility. 1st ed. Routledge, 2017.

- 21

Abreu, Kristine De. “War Tourism: From the Crass Selfie to the ‘Never Again’ Lesson » Explorersweb.” Explorersweb, January 26, 2023.

- 22

American Battlefield Trust. “Bull Run.” Accessed April 22, 2024.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)