Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery

On a warm, sunny day in June of 1914, a crowd gathered to witness the unveiling of what The Washington Post described as “a memorial of heroic size, commemorating war, but dedicated to peace.” It was an intricately designed, 32-foot tall granite monument deeply embedded with symbolic meaning for visitors to decode. A large statue of a woman facing southward dominated the top of the monument. In her extended arm was a laurel wreath meant to represent the sacrifices of fallen soldiers. Below her, a Biblical passage was inscribed, near four urns that symbolize the four years of the Civil War, and fourteen shields. Closer to the monument’s base are thirty-two life-sized figures, including Southerners of varying military branch, race, gender, occupation, and age, along with mythological characters such as Minerva, Goddess of War.[1]

So what was this new monument and why were so many people clamoring to see it? Well, it was the cemetery’s first Confederate Memorial, which was a huge development, given Arlington’s origins.

The cemetery started out in 1864 as a burial place for fallen Union soldiers, on land that had belonged to Robert E. Lee’s family before they fled south during the Civil War.[2] Many viewed this as a purposeful jab at the general and his Confederate army. From the beginning and for several decades afterward, the cemetery was intended only for Union soldiers and burial of Confederates was discouraged.[3]

In 1901, however, Congress and Arlington National Cemetery authorities changed the policy in the interests of national reconciliation. Hundreds of Confederate soldiers from area cemeteries were brought to Arlington and reburied in a section that would be designated as a uniquely Southern space: Jackson’s Circle in Section 16. It was one of several initiatives from the early 20th century that tried to mend tensions between North and South, still strong even though the Civil War had ended almost half a century earlier. (Another example was the construction of Memorial Bridge between the Lincoln Memorial and Arlington House, the Lees’ former home, in the 1920s. The bridge was intended to represent a physical bond between North and South.[4])

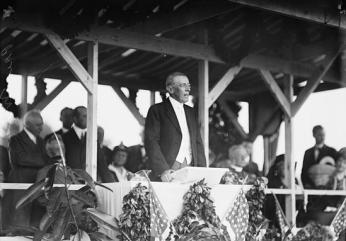

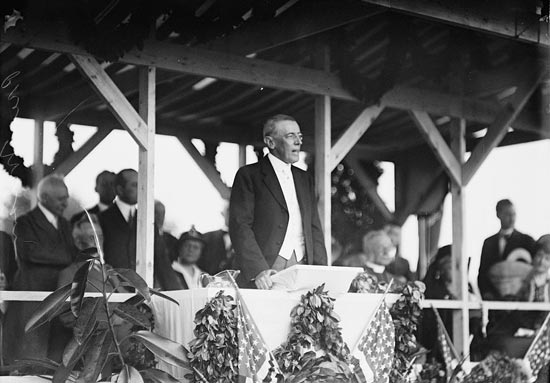

The unveiling ceremony took place on June 4th, the day after Confederate president Jefferson Davis’s birthday.

It had attracted a crowd of about 4,000 people, including military personnel from all over the country as well as D.C.-area residents. They were eager to witness the unveiling along with President Woodrow Wilson, who was scheduled to give a speech. Other notable attendees included the monument’s sculptor Moses Ezekiel, a Confederate veteran himself, Col. Robert E. Lee, grandson of the general, and members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who had commissioned the monument.

Morbidly enough, the crowd was positioned in Section 16 between the Confederate headstones, which to this day stand out as being unlike any other headstones in the cemetery. When the Confederate re-burials took place, the cemetery chose to implement a unique design for marking the graves of these soldiers: pointed, instead of rounded, headstones. While the official purpose of the peaked top was to differentiate the resting places of Confederate soldiers from those of the Union army, Southerners developed their own explanation. They claimed that the pointed style would “keep Yankees from sitting on them.”[5] This design originating at Arlington National Cemetery went on to be adopted for use at Confederate gravesites around the country.[6]

As the crowd stood between these unique headstones during the ceremony, they noticed a sudden wind picking up speed and ominous black clouds gathering in the distance. An unexpected thunderstorm was fast approaching the cemetery. By the time President Wilson got up to speak, the dark clouds were upon them. He spoke hurriedly, warning the crowd of the dangerous weather conditions, and eventually cut his speech short in order to drive back to the safety of the White House. A reporter described what resulted for the remaining crowd-goers caught in the torrential rain as “a wild dash for automobiles and trolley cars, participants and spectators alike forgetting the almost finished program.”[7]

While it’s unlikely that many stopped to consider it at the time, the dark clouds were an appropriate metaphor for the memorial. The design — which includes an enslaved woman holding the baby of a white Confederate officer, and enslaved men following their master to war — is a testament of the Lost Cause ideology, which was prevalent at the beginning of the 20th century.

As described in the Encyclopedia of Virginia, the Lost Cause “created and romanticized the ‘Old South’ and the Confederate war effort, often distorting history in the process.” It was developed by white Southerners who sought to interpret and present the Civil War in terms that were sympathetic to the Confederacy. The ideology gave rise to thousands of Confederate monuments around the country including at Arlington National Cemetery.

While accepted and, in many cases, officially embraced 100 years ago, the imagery of these memorials frustrated activists and historians over time. They came into sharper focus for the general public after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. In an effort to confront racial injustice, the U.S. military created a panel to review Confederate symbols and names on military installations. In September 2022, the commission recommended that the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery be removed, calling it “problematic from top to bottom.” That removal is slated for December 2023.

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/VisitorInformation/MonumentMemorials/Confederate.aspx

- ^ http://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/History/Facts/ArlingtonHouse.aspx

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/history/nr/travel/national_cemeteries/text_only.html

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc69.htm

- ^ http://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/VisitorInformation/MonumentMemorials/Confederate.aspx

- ^ http://ncptt.nps.gov/blog/confederates-in-the-cemetery-federal-benefits-stewardship/

- ^ GRAY AND BLUE JOIN. (1914, Jun 05). The Washington Post (1877-1922). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/145322049?accountid=14541

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)