Meet the “Georgetown Witches,” Margaret Ann and Belle Laurie

Those who think that the “Exorcist stairs” are the spookiest landmark in Georgetown clearly haven’t heard of the Laurie family. In the nineteenth century, in a townhouse where 3327 N Street NW stands today, two women known as “the Witches of Georgetown” were talking to ghosts and making pianos levitate.1 Or, at least, that’s what legend tells us—and what the Laurie family wanted their clients to believe. Margaret Ann Laurie and her daughter, Belle, were professional psychic mediums. Part of a circle of “spiritualists” in Washington, who believed in communication and connection with the dead, they hosted séances in the parlor of their Georgetown home.

For some in mid-nineteenth-century Washington, this was a stylish form of entertainment—for others, a deep-rooted belief that provided comfort in a time of immense loss. Spiritualism, a fringe movement that began in upstate New York in the 1840s, was gaining traction in cities on the East Coast. They were especially interested in answering a timeless question: what happens to the soul after death? Most spiritualists were convinced that, once in Heaven or Hell or the spirit realm, a soul could still find ways of communicating with those left behind on Earth.

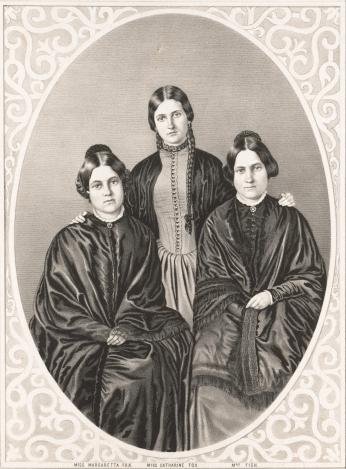

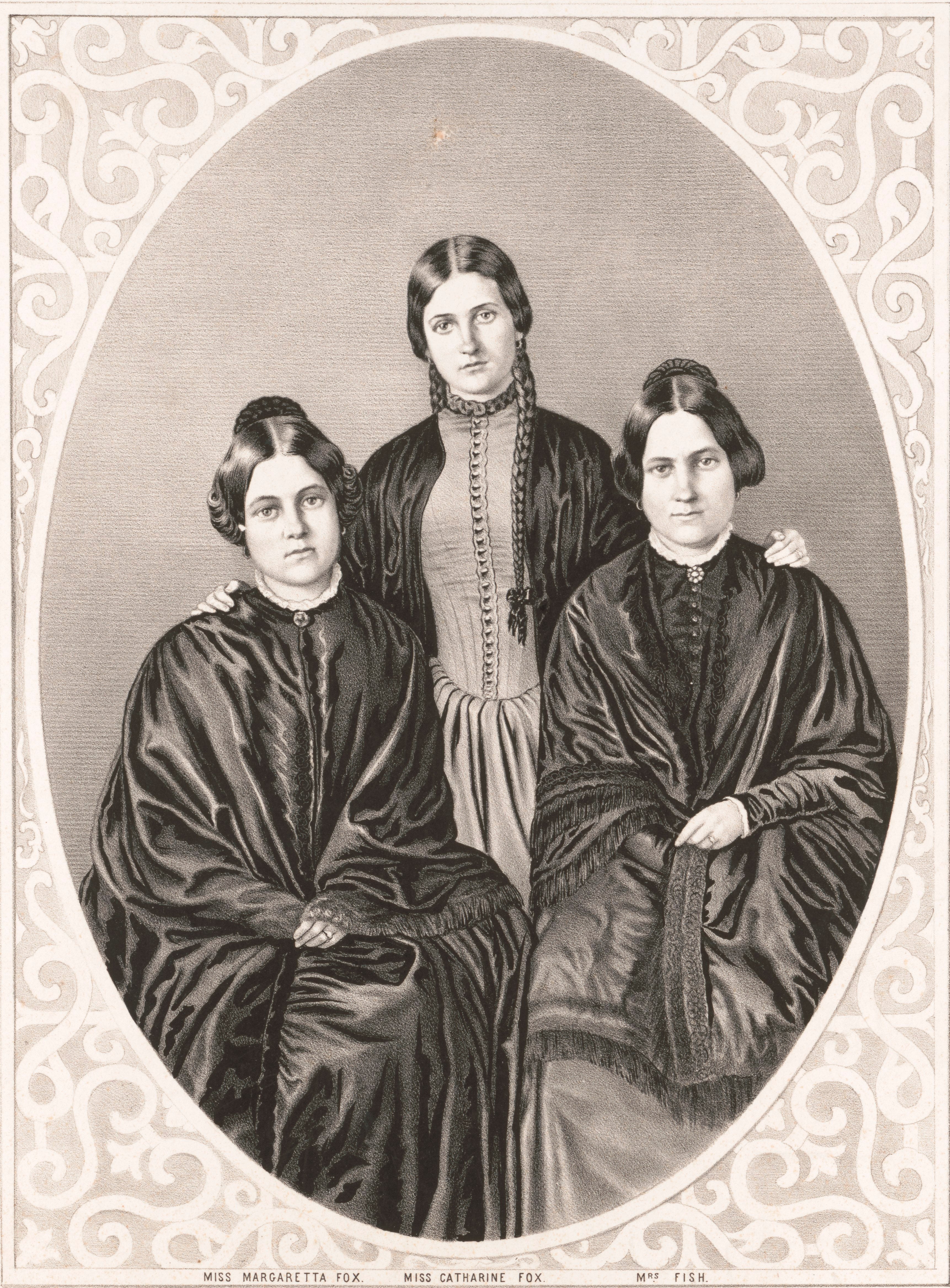

Soon, however, it was the theatrical displays that piqued mass public interest. In 1850, the first famous mediums of the movement—the Fox Sisters of Rochester, New York—began to advertise public séances at locations all around New York City.2 According to participants, the sisters entered trance-like states and asked spirits to communicate through a series of raps, or knocks, establishing their presence and answering questions. Their methods were so exciting and convincing that they eventually took their show on the road, even coming to Washington, D.C. in the mid-1850s to show off their talents. While some were enchanted, others were less convinced by the show. One Washington newspaper described the sisters’ performance as “farcical solemnities and absurd blasphemies.”3 Likewise, the Alexandria Gazette dismissed them as “spirit rappers.”

Nevertheless, the success and popularity of the Fox Sisters sparked interest in spiritualism. In Washington, mediums were certainly performing acts that defied believability. The Laurie family—Cranston, Margaret Ann, and their daughter Belle—were quickly becoming the city’s most sought-after mediums thanks to the success of their Georgetown séances. The 1871 Year-Book of Spiritualism, a spiritualist magazine, remembered that, “the whole of Mr. Laurie’s highly-gifted family display mediumistic powers.”4 During a typical séance, the Lauries acted as interpreters for communication, asking spirits to speak through rappings or by taking control of objects and minds. Through something she called “magnetic” techniques, Margaret Ann was able to transmit messages to those at her table.5 Cranston and Margaret Ann also produced “spirit drawings,” works of “wonderfully abnormal” art inspired by the spirits with whom they connected.6 Their secret weapon was Belle, called “one of the most powerful physical mediums,” who played a levitating piano during sessions, terrifying and humbling her patrons.7

To give you an idea of what the Lauries were up to, in March 1854, the Evening Star reported that the Lauries were present at a séance that summoned the spirit of the famous Congressman and Secretary of State Daniel Webster:

“Last night, quite a scene took place at Captain Bruff’s, at the corner of 19th and K Streets…the spirit rappings and talkings having been both numerous, interesting, loud and frequent… It would be impossible, within our limited space, to give even a brief sketch of all that transpired…In the course of the evening, the spirit of Daniel Webster prophesied that the Nebraska bill would never pass…There were several other manifestations, questions being put by different lookers-on, which were, it appears, satisfactorily answered, the spirit replying with one, two, or three raps, according as he wished to imply positive certainty or not. What are we coming to? This is a strange world, with all manner of people in it.”8

Undoubtedly, though, the Lauries’ most famous client was the First Lady: Mary Todd Lincoln. Both Lincolns were inconsolable after the death of their eleven-year-old son, Willie, and Mary turned to spiritualism as a way to cope with her loss. In 1862, shortly after Willie’s death, she was introduced to the Lauries and attended private sessions with them at their Georgetown townhouse.9 The mediums proved convincing—Mary became an obsessive spiritualist. She eventually invited the Laurie family to conduct séances within the White House itself—evidence suggests that they visited the Red Room at least eight times.10

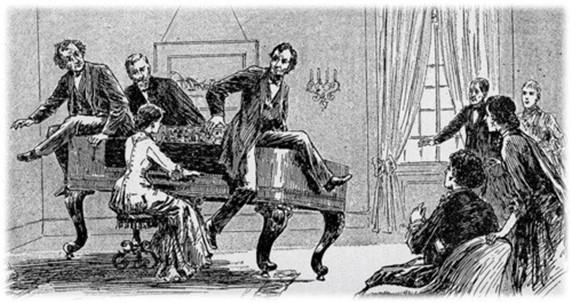

Following the death of Abraham Lincoln, the Laurie family claimed that they had even made a spiritualist out of the late President. It’s certainly possible—likely, even—that Abraham attended the White House séances at the urging of his wife and there met the Laurie family.11 But they also insisted that both Lincolns made a special trip to visit them in Georgetown. In 1891, the Lauries’ associate and fellow medium Nellie Colburn Maynard wrote a memoir entitled Was Lincoln a Spiritualist?, in which she colorfully describes the President’s visit to the Lauries’ parlor and his conversion to the movement. Apparently, a curious Lincoln was bewildered and amused when Cranston Laurie greeted him at the door and told him that he was expected. “Expected!” he exclaimed. “Why, it is only five minutes since I knew that I was coming.”12 Later, he was equally as amazed when Belle used her “influence” to levitate the piano as she played it—when she suggested that the President attempt to debunk it, he sat on the piano but couldn’t stop it from floating, later admitting that it seemed to have been moved by “an invisible power.”13

As fun as these stories are, there’s no real evidence that Abraham was a believer in the séances that his wife insisted on attending. In fact, Cranston Laurie himself admitted that it would be “hardly advisable” for the President to be seen at the residence of the Georgetown Witches, since spiritualism was still mocked in most circles.14 Still, the Lauries used publications like this to add to their credibility as Washington’s most famous mediums. Mary Todd Lincoln stayed in touch as her obsession with ghosts increased, apparently sending Margaret Ann and Belle a lock of Abraham’s hair as a way to summon his spirit more effectively—the hair and note is now in the collection of the Chicago Historical Society. The Lauries remained in business until their respective deaths in the 1870s and 1880s, when they were interred at the Congressional Cemetery.15

But was the Georgetown townhouse really such a haunted house? Obviously, the Lauries’ followers believed so. By the 1880s, following the massive death toll of the Civil War, spiritualism was at its peak, with an estimated eight million believers in the United States.16 But interest began to wane as mediums admitted the practical tricks behind their séance shows. In 1888, Maggie Fox admitted that she and her famous sisters learned to manipulate their joints and knuckles to discreetly create the “spirit rappings” that so captivated their audiences.17 Though they never admitted to anything themselves, it’s likely that the Lauries also learned to use such methods, especially as their notoriety increased demand for sensational acts. Even with President Lincoln sitting on her piano, Belle probably had a way to manipulate it so that it appeared to be floating. Robert Lincoln certainly believed that the Lauries and other mediums who surrounded his mother weren’t really doing anything to comfort Mary Lincoln’s grief—only taking advantage of a depressed and famous client for their own gain.18

Then again, perhaps we’re all wrong. As the Evening Star journalist so aptly put it, “This is a strange world, with all manner of people in it.”19

Footnotes

- 1

Emilia Ferrara, “In Search of the Witches of Georgetown,” The Georgetowner (12 October 2022).

- 2

Karen Abbott, “The Fox Sisters and the Rap on Spiritualism,” Smithsonian Magazine (30 October 2012).

- 3 The Washington Union (Washington, D.C., 30 April 1854), page 2, column 5.

- 4 Emma Hardinge, “Spirit-Art,” The Year-Book of Spiritualism for 1871, ed. Hudson Tuttle and JM Peebles (Boston: William White and Company, 1871).

- 5 Ferrara, “In Search of the Witches of Georgetown.”

- 6 Hardinge, “Spirit-Art.”

- 7 Nettie Colburn Maynard, Was Lincoln a Spiritualist? (Philadelphia: Rufus C. Hartranft, 1891), 55.

- 8 “Spirit Rappings,” The Evening Star.

- 9

“That’s the Spirit!,” National Archives Foundation Newsletter (25 October 2022).

- 10

Alexandra Kommel, “Seances in the Red Room,” the White House Historical Association (24 April 2019).

- 11 Ibid.

- 12 Maynard, 88.

- 13 Maynard, 91.

- 14 Maynard, 82.

- 15

Lauren Malo, “Not Dead, But Arisen: Victorian Spiritualists in Congressional Cemetery,” Congressional Cemetery (25 June 2012).

- 16 Abbott, “The Fox Sisters and the Rap on Spiritualism.”

- 17 Ibid.

- 18 Kommel, “Seances in the Red Room.”

- 19 “Spirit Rappings,” The Evening Star.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)