In 1969, Vince Lombardi Brought Winning and Inclusivity to Washington

Vince Lombardi wasn’t planning to continue coaching after he resigned as head coach with the Green Bay Packers. Instead, he was going to get away from that stress-filled lifestyle and move into a general manager position with the Packers. “I’m still a young man, but I doubt I would ever go back to coaching,” Lombardi said when he moved to the front office after the 1967 season.1

After just a year as general manager, he found himself longing to be on the sidelines again. “I’m certainly getting a little itchy,” Lombardi admitted in August of 1968. Soon enough, this itch overcame his life.2

Over the next few months, various news sources teased fan bases around the league, all of which dreamed that the legendary coach might come to their town. On February 2nd, 1969, a Washington Post headline announced the coach’s decision: “Lombardi Acts To Join Redskins.”3

A large part that drove Lombardi to take the position in Washington came from his wife’s desire to live on the east coast. Mrs. Lombardi had struggled living in Green Bay, overusing drugs and alcohol, and wanted Lombardi to get back into coaching. "My wife wants me back coaching. She told me I was a damn fool to get out of it,” he remarked.4

He had been picky over his decision of what team to join, though, turning down offers from the Boston Patriots and Philadelphia Eagles because of his overall preference for Washington. “Why did I choose Washington among offers from other cities? Because it is the capital of the world. And I have some plans to make it the football capital.”5

Lombardi’s desire to win had not waned during his short stint away from coaching. Immediately after accepted the position in Washington, he famously declared that he “will demand a commitment to excellence and to victory.”6

He certainly had a proven track record. Prior to his arrival in Green Bay in 1959, the Packers had not had a winning season in 11 years. Over the next nine seasons, he led the team to five league championships including victories in the League’s first two Super Bowls.

Be that as it were, Washington may have been in worse shape in 1969 than the Packers had been when Lombardi got there. The Redskins had consistently finished in the lower rungs of the league standings for years and had been mired in controversy due to their reluctance to integrate. Washington was the last team in the league to sign any black players and only did so reluctantly in 1962 when the Federal government threatened to prohibit them from playing in the brand-new D.C. Stadium.7

Although some were skeptical if Lombardi’s skills would be able to translate to the Redskins, fans kept faith.8 After news broke of Lombardi coming to Washington, fans flooded local news departments with calls to confirm if it was true.9 The potential of the greatest football coach coming to their team filled them with anticipation. After all, if he couldn’t turn the team around, who could?

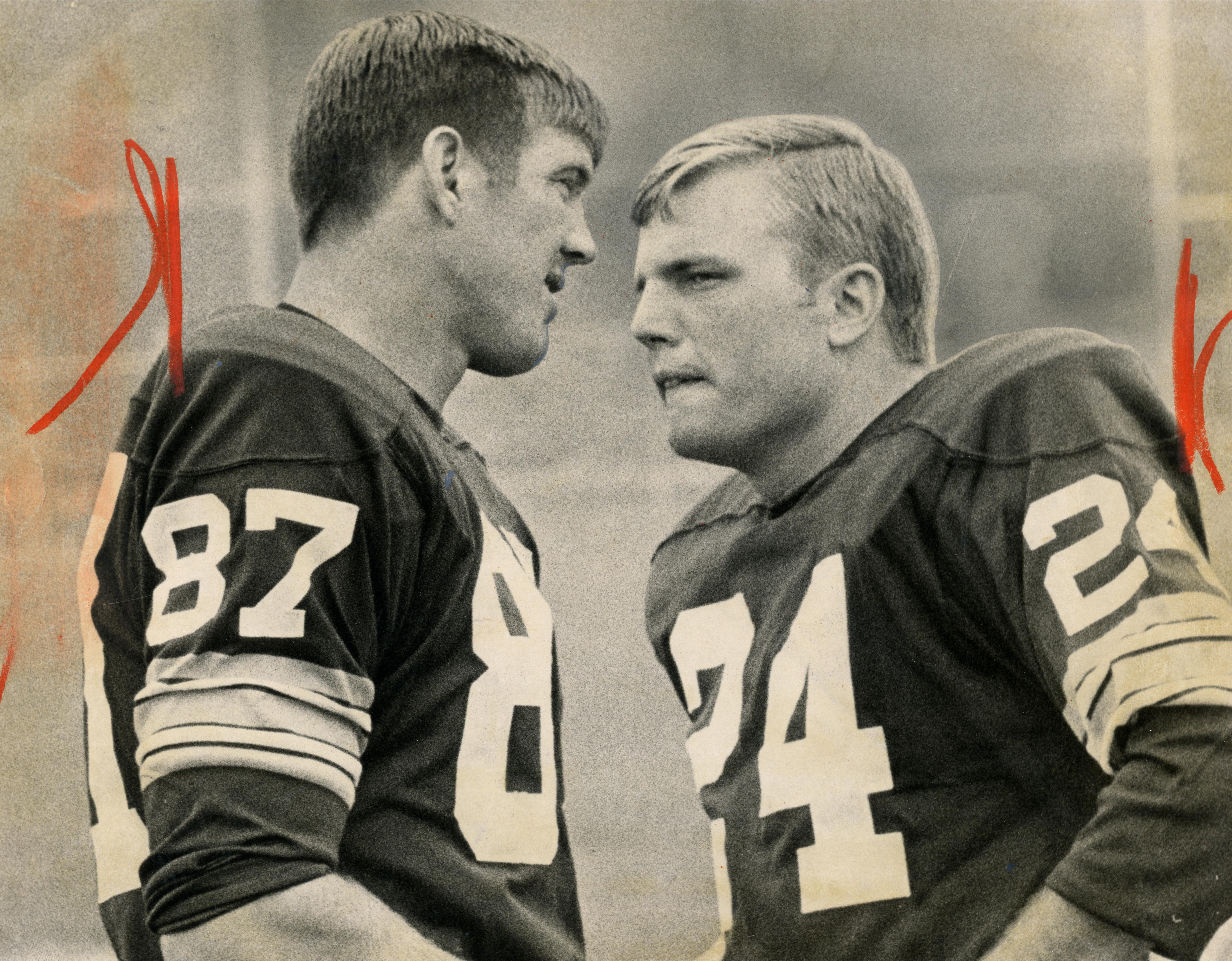

Lombardi kicked off his tenure with a “four-day orientation program” in June of 1969, so the coach could get a feeling of what he was working with. As he told the Washington Post, there were reasons for optimism, remarking “This is more team speed than I’ve seen around.” Though training seemed to get off to a good start, Lombardi’s no-nonsense coaching tactics kicked in too.10

On just the first day, Bill Kushner, quarterback, and Bob Brookshire, linebacker, were cut and other players were pushed to exhaustion. Bob Brunet, a running back, recorded feeling “sluggish all week” and “disappointed” with his physical condition.11

The demanding practices were not unusual for players under Lombardi, though. Ray Schoenke, a guard from Green Bay recalled his experience in Lombardi’s training camp as “the hardest six weeks of my life.” He appreciated the hard work demanded by his ex-coach, though, stating that “he drives you to the limit physically and then on top of that adds mental pressure. But that’s what you need to be a winner.”12

And winners the Redskins became. Just one year after the team had limped to a 5-9 finish under Otto Graham in 1968, Lombardi drove the team to a 7-5-2 record in 1969. Though the on-field turnaround was dramatic – Washington posted its first winning record since 1955 – it was only part of Lombardi’s impact.

In addition to his well-known “winning isn't everything, it is the only thing,” coaching mindset, Vince Lombardi was a strong advocate for equality. As Slate writer Johnny Smith observed in 2017, the coach’s politics were complicated – he “embodied a mixture of conservative and liberal impulses.” But one thing was certain: he abhorred discrimination.13

As an Italian American, Lombardi had faced discrimination for his darker complexion as his skin tanned very easily. In one trip to Winston-Salem with his wife, a hostess refused him service because of the darkness of his skin.14

Lombardi experienced secondhand discrimination through his football players’ experiences as well. During his time at the Packers, the integrated team was refused service while traveling through the Jim Crow South in the 60s. To ensure that no black players on his team would feel ashamed or degraded because of their skin tone, Lombardi declared that all Packers would stay in the same establishments on the road.

In his book entitled Closing the Gap, former Packers defensive end Willie Davis recalled that "Right from the start [Lombardi] treated us as equals, just players competing for a spot on the team. He chose not to see color in an era where most chose to look the other way."15

Lombardi’s colorblind approach to roster building continued in Washington. So, too did his inclusive attitudes toward homosexual players.

Lombardi’s personal connection to homosexuality came through his brother, Harold, who was gay. Harold came out to his parents through a letter after relentless questions about when he would get married. Harold recalled being “very nervous waiting for a response,” but his father responded simply, “I don’t care. You are my son.”

Likewise, Vince knew about his brother’s sexuality and decided to ignore his firm Catholic teachings against homosexuality to silently support his brother.16 Although the two brothers never spoke about Harold being gay, Vince displayed his acceptance through the way he treated his players.

When Lombardi arrived to coach the Redskins in 1969, discrimination against LGBT Americans was not only the norm, it had been codified for almost 20 years. Beginning in the 1950s, in what became known as the Lavender Scare, the Federal government had undertaken a decades-long effort to remove gay men and lesbians from Federal jobs.

It was common for workers to lose their jobs at the slightest hints that they were gay which caused many to remain in the closet. This was the same truth facing players in the NFL during the 1960s.

“Back then gay people were almost thought of as deviant. It was really terrible at the time,” remarked Dave Kopay, who played nine years in the NFL – including two seasons in Washington – before retiring and becoming the first professional athlete to come out publicly.17

Most homosexual players never felt safe enough to come out, and many to this day choose to stay private about their sexuality. However, Lombardi did his best to make homosexual players feel respected and equal in a time when mainstream American society did not. Susan Lombardi, Vince’s daughter, best sums up the coach’s treatment of his players, gay and straight alike: "My father treated them all the same. Like dogs."18

Although his actions were not commonly or publicly spoken about at the time, more recent memoirs and personal accounts of Lombardi’s time at the Redskins have shed light on the coach’s impacts.

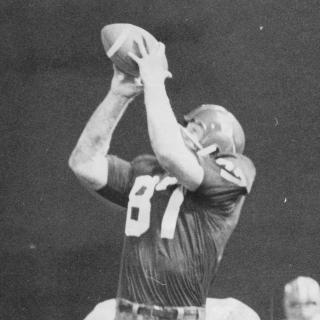

In a 2014 documentary for NFL Films, Hall of Fame receiver Charley Taylor recalled that the Redskins became known for fostering a welcoming environment for gay players. “We had a reputation across the league. The Redskins had more gay guys than anybody. We had 12 at one time, I think. We were just playing football. We didn’t care. If you could play, we didn’t worry about that.”19

These players included Ray McDonald, who was struggling to recover from a hurt Achilles tendon during Lombardi’s 1969 training camp. Rumors of McDonald’s sexuality had been swirling around some time at that point, which made him a target to some assistant coaches. Lombardi protected this player from potential harassment by instructing his staff to help the running back make the team. “And if I hear one of you people make reference to his manhood, you’ll be out of here before your ass hits the ground.”20

(As fate would have it, McDonald ended up being cut from the team. It was not because of his homosexuality, however. Rather it was due to Lombardi having issues with the player showing up late to a team meeting – a cardinal sin in Lombardi’s eyes, as he was obsessed with punctuality.)

Jerry Smith was another closeted gay player who excelled for the team and had a very close relationship with Lombardi. "Lombardi protected and loved Jerry," Dave Kopay recalled about his former teammate and coach. Smith, who became one of the top tight ends in the league, enjoyed perhaps his finest season under Lombardi, earning All Pro honors in 1969.21

Vince Lombardi’s time in Washington came to an unexpectedly abrupt end after just one season. On September 3, 1970, the coach passed just ten weeks after he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of colon cancer. His players and the city mourned greatly for the loss of the coach they only got to know for a year. Mike Bass, cornerback for the Redskins reflected that "Not only was he our coach, he was the whole city's coach, including Richard Nixon. [Lombardi] brought that city together. We became celebrities. Wherever we went in Washington we were greeted with open arms and everyone wanted to talk about Lombardi and what he was like."22

Reflecting on his career, that legacy was twofold. On the field, Lombardi transformed the Redskins into a winning team. Off the field, he made them a more inclusive one. In a time where racism ran rampant throughout the country, Lombardi stuck up for his players. In a time where gay athletes “would’ve been blackballed” if they came out as gay while they were professional athletes, Lombardi did his best to provide a haven for them.23

Perhaps no player felt the coach’s influence more than Jerry Smith. In 1986, Smith was diagnosed with AIDS at age 43. Just 51 days before his death, he agreed to a formal interview with The Washington Post to share his disease with the public and help change the stereotype of HIV and AIDS. “Maybe it will help people understand. Maybe it will help with development and research. Maybe something positive will come of this,” he stated. When he was on his deathbed, he reflected on his relationship with Lombardi, the coach who made him feel safe in an unsafe world. “Every important thing a man searches for in his life, I found in Coach Lombardi. He made us men."24

Footnotes

- 1 Lombardi Is Itching For Piece of Action: But He Might Not The Weekend Itch Lombardi Hits Rumors,” Washington Post, November 13, 1968.

- 2 William Gildea, “Lombardi Is Getting Itchy,” Washington Post, August 3, 1968.

- 3 Martie Zad, “Lombardi Acts To Join Redskins: To Ask Release From Packers Lombardi Acts to Join Redskins Green Bay Release Due On Monday Rejected Boston Bid No Shock To Graham,” Washington Post, February 2, 1969.

- 4 Dave Brady, “Mister Lombardi Comes to Washington: 'I Will Demand a Commitment To Excellence,' New Chief Says Lombardi Takes Full Power Quickly 'No Preconceived Notions' Silent Graham Stick To His Golf Game,” Washington Post, February 7, 1969.

- 5 Zad, “Lombardi Acts To Join Redskins.”

- 6 Brady, “Mister Lombardi Comes to Washington.”

- 7 Benjamin Shaw, “’The Whitest Huddle of Any Team in the League,’” Boundary Stones, August 14, 2015.

- 8 David Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), 465.

- 9 Lombardi Looks Set, But Wait Drags Out,” Evening Star, February 4, 1969.

- 10 William Gildea, “Drills Build Pressures On Redskins: Schoenke Has Advice Brunet Eases Up,” Washington Post, June 22, 1969.

- 11 William Gildea, ”Redskins Off to Fast Start: Lombardi Likes Team's Speed,” Washington Post, June 18, 1969.

- 12 Gildea, ”Drills Build Pressures On Redskins.”

- 13

Johnny Smith, ”Vince Lombardi Would Be Proud,” Slate, September 30, 2017.

- 14 Smith, ”Vince Lombardi Would Be Proud.”

- 15

Alex Bysouth, ”Super Bowl 2020: Vince Lombardi, the story behind the name on NFL's biggest prize,” BBC, January 30, 2020.

- 16 Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered, 343-44.

- 17 O’Connor, ”Lombardi.”

- 18

Ian O’Connor, ”Lombardi: A champion of gay rights,” ESPN, May 2, 2013.

- 19

"Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life,” NFL Films, uploaded Sep 29, 2023, video.

- 20

David Maraniss, ”Won and Lost,” Washington Post, September 5, 1999.

- 21 O’Connor, ”Lombardi.”

- 22

John Keim, ”’You fought like mad for him’: Stories from Vince Lombardi’s season coaching Washington,” ESPN, October 20, 2022.

- 23

Scott Allen, ”Washington’s Jerry Smith among those who paved the way for Carl Nassib’s coming out as gay,” Washington Post, June 24, 2021.

- 24 Allen, ”Washington’s Jerry Smith."

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)