After Becoming an NFL Star in Washington, Jerry Smith Battled AIDS

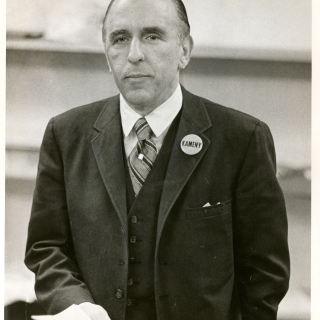

Of all the sports legends to emerge from Washington, DC, few achieved such greatness while battling so much adversity as Redskins tight end Jerry Smith. In 13 seasons with the team, from 1965 through 1977, Smith made two Pro Bowls, set the league record for career touchdown receptions by a tight end (60), and appeared in a Super Bowl.1 in 1986, Smith also became the first professional athlete to announce he was suffering from acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, better known as AIDS.

Smith died at Holy Cross Hospital in Silver Spring, Maryland, on the evening of October 15, 1986, at the age of 43, just months after detailing his struggle with the disease to Washington Post journalist George Solomon.2 Smith’s disclosure helped foster awareness at a time those afflicted with AIDs faced widespread discrimination, ostracization, and denial of care.

“I want people to know what I've been through and how terrible this disease is," Smith told Solomon in his hospital room.3 “Maybe it will help people understand. Maybe it will help with development in research. Maybe something positive will come out of this."

Smith’s decision to reveal his diagnosis did not come easy, nor did being a closeted gay player in an era when opening up about one’s sexuality could risk losing everything. Despite immense professional and personal challenges, Smith never lost his trademark smile and selflessness that his Washington teammates still remembered decades later.

“The man showed enormous courage and left a great legacy,” David Mixner, a gay rights activist who was Smith’s friend and Arizona State University classmate, said in a 2014 episode of NFL Films’ A Football Life documentary series.4 “He was one of the kindest, most gentle, got-your-back type guys you ever could meet.”

Born on July 19, 1943, in Eugene, Oregon, Gerald Thomas “Jerry” Smith did not seem destined for an NFL career, let alone stardom, from an early age.5 Bonnie Smith Gilchrist recounted to NFL Films how a high school coach questioned why her skinny brother was even trying out for the football team.6

“He didn’t take the easy way,” Bonnie said of Smith, who attended a junior college before walking on at Arizona State, where he converted from wide receiver to tight end.7 The determination paid off and Washington selected Smith in the ninth round of the 1965 NFL draft with the 118th overall pick.8

“Jerry was so excited,” Smith Gilchrist said in a 2022 interview with the team about her brother’s legacy.9 “I mean, here's a 21-year-old guy, going to the nation's capital. That was a real big thing, and it was the first part of a journey.”

Used to being underestimated, Smith quickly excelled as a pass catcher, joining a dynamic receiving corps that also featured Bobby Mitchell, the first black player in Redskins history, as well as Smith’s Arizona State teammate Charley Taylor.

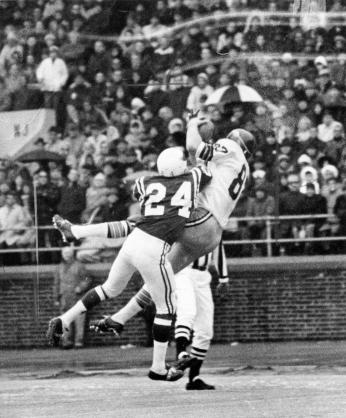

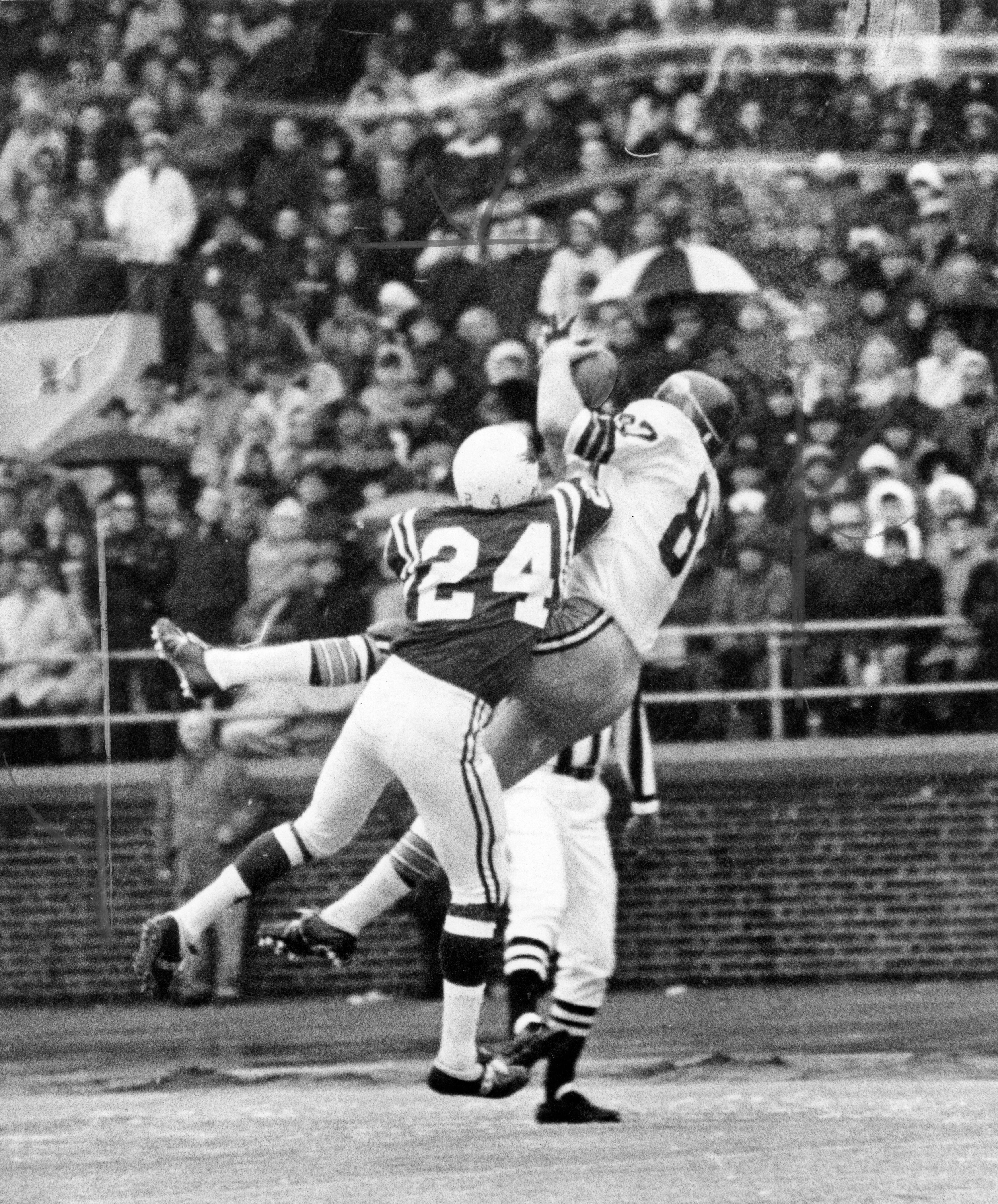

Smith drew praise for his speed, anticipation, and—above all—great hands, attributes that helped him haul in more catches for more yards than any other tight end in the league between 1966 and 1970.10 During his Pro Bowl-worthy 1967 season, Smith had 12 touchdown receptions, tied for the single-season franchise record until Terry McLaurin surpassed it earlier this year (Smith achieved his mark with three fewer games on the schedule).11

“He became a go-to guy for me,” Washington quarterback Sonny Jurgensen reflected in A Football Life.12 “He was outstanding. When you needed a play to be made, you knew that you could throw the ball to him and some way, somehow, he was gonna catch the thing.”

Smith earned a sterling reputation both on and off the field, especially when it came to how he treated others. In 1966, at the height of the civil rights movement, he and safety Brig Owens decided to bunk together during training camp and on road games, becoming the NFL’s first interracial roommates.13

When Owens warned Smith the move would stir controversy, the tight end replied “So what?"14 The two remained steadfast friends for the remainder of their careers, with Owens’ daughters affectionately referring to Smith as “Uncle Jerry.”15

Inclusivity became further ingrained in the team’s culture when legendary former Green Bay Packers head coach Vince Lombardi took the helm in Washington for the 1969 season. Under his gruff, disciplinarian exterior, Lombardi, who had a gay younger brother, believed strongly in equality and preached tolerance in the locker room.

“We had a reputation across the league,” Charley Taylor told NFL Films.16 “The Redskins had more gay guys than anybody. We had 12 at one time, I think. We were just playing football. We didn’t care. If you could play, we didn’t worry about that.”

Lombardi’s coaching, coupled with Smith and the rest of the offense’s explosive production, propelled Washington to a 7–5–2 season, the franchise’s first winning record in 14 years.17 While Lombardi tragically died from cancer in 1970, the team sustained its newfound success under head coach George Allen, appearing in its first Super Bowl in 1972 against the Miami Dolphins.

In a heartbreaking 14–7 loss to Miami at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Washington quarterback Billy Kilmer missed a wide open Smith in the end zone late in the fourth quarter as the ball bounced off the crossbar of the goal post, which in those days still stood in play.

Allen’s coaching tenure featured a defensive style of play that relied on Smith more as a blocker than a pass catcher. Despite his reduced offensive output—and his undersized 210-pound frame going up against far heavier pass rushers—Smith never complained, helped mentor fellow tight end Jean Fugett, and remained, in his sister’s words, “a consummate teammate.”18

Smith accomplished all this while keeping his sexuality a closely guarded secret, one he feared would ruin his career if exposed. Even if individual locker rooms like Washington’s were more tolerant, the NFL, like most American institutions at the time, viewed homosexuality as a moral and societal threat.

“If there actually were a homosexual in the league, which I have no evidence that there is, if you have a homosexual he’s always subject to possible compromise,” NFL Director of Security Jack Danahy said in 1975.19 “There’s been a history in espionage activities in international affairs of homosexuals being compromised and used against their better interests. So that would naturally be a matter of concern to us.”

“[Smith] faced fear, and I can tell you this cause we talked about it, every day of his life that he played,” Jerry’s friend Mixner said.20 “From day one, Jerry wanted to play ball. I mean this man loved football. He was living his dream and if anyone had known he’d be gay, they would snatch that dream from him, forever.”

That fear was tested in 1975, when Washington Star reporter Lynn Rosellini interviewed Smith at the Key Bridge Marriott for what Smith thought would be a standard player profile. In reality, Rosellini, who contacted Smith at the advice of her colleagues, was writing a series about gay athletes.21

When Rosellini said she wanted to talk to Smith for the series, the two sat in momentary silence before Smith replied “okay,” so long as the reporter didn’t use his name or say what team he played for or his position.22 The resulting article documented Smith’s “two lives” as a gay NFL star, helping him to finally “breathe some freedom,” according to Mixner.23

While not naming Smith, Rosellini did describe his “massive and scarred hands,” which identified him to former Redskins teammate David Kopay.24 Kopay, then three years into retirement and still in the closet, called Rosellini and said he’d tell her his own story and go on the record—becoming the first retired football player to publicly come out as gay.25

In his subsequent 1977 autobiography The David Kopay Story, Kopay recounted a one-time sexual encounter he had with Smith while they were teammates after which Kopay said the star tight end “rejected me cold.”26 Although the book referred to him by a pseudonym, the depiction left Smith feeling betrayed and he never spoke to Kopay again.

The same year the book released also proved to be the increasingly injury-prone Smith’s last in the NFL, after which he eventually moved to Texas and co-owned a gay bar.27 But in December 1985 while in DC, a visibly thinner and fatigued Smith was taken to Holy Cross Hospital where he tested positive for AIDS.28

During Smith’s stay at Holy Cross a hospital spokesperson remarked that every third call was for him and he received frequent visitors, many of them former Redskins.29 Though he declined to “elaborate on his life style,” Smith made the decision to speak with Solomon at The Post about the disease, which he continued to fight even as his weight dipped to 150 pounds.30

Smith died in October 1986 following a nearly year-long battle with AIDs. Several teammates including Jurgensen, Taylor, Mitchell, and ex-roommate Owens served as pallbearers at his funeral at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Silver Spring.31 Owens lingered alone at the cemetery afterwards, according to The Washington Post, placing a red carnation atop his best friend’s casket before two workers lowered it into the ground.32

“Jerry loved crossing the goal line and hopping and skipping back toward the sideline, into the arms of his teammates,” longtime Redskins chaplain the Rev. Tom Skinner said at the service.33 “I believe if we saw Jerry now, he would be hopping and skipping and jumping, because he is in heaven."

Though his family and teammates have never forgotten him, Smith’s legacy remains sorely overlooked by the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In spite of amassing more receptions (421) than three Hall-of-Fame tight ends and holding the record for career touchdown catches at his position for 27 years until 2003, Smith has yet to be enshrined in Canton.34

“He was a great player, and he belongs in the Hall of Fame,” Owens told The Post in 2021.35 “He still needs to be considered...He has the numbers despite playing fewer games and a different brand of football.”

Footnotes

- 1

“Jerry Smith,” Pro Football Reference, accessed 20 June, 2025, https://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/S/SmitJe01.htm

- 2

Christine Brennan, “Family, Friends Gather For Jerry Smith Funeral,” The Washington Post, 21 October, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1986/10/22/family-friends-gather-for-jerry-smith-funeral/4c1b79a5-8beb-43f3-a1c1-615ac1612cd9/

- 3

George Solomon, “Ex-Redskin Jerry Smith Says He's Battling AIDS,” The Washington Post, 25 August, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/08/26/ex-redskin-jerry-smith-says-hes-battling-aids/dae98b5e-1111-4b7e-9c2d-68cd68a8c0d2/

- 4

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 5

“Jerry Smith,” Pro Football Reference, accessed 20 June, 2025, https://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/S/SmitJe01.htm

- 6

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 7

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 8

“1965 NFL Draft,” Pro Football Reference, accessed 20 June, 2025, https://www.pro-football-reference.com/years/1965/draft.htm

- 9

Hannah Lichtenstein, “'A team guy right to the end': Reflecting on the legacy of Washington Legend Jerry Smith ahead of Pride Night Out,” Official Site of the Washington Commanders, 20 September, 2022. https://www.commanders.com/news/reflecting-on-the-legacy-of-washington-legend-jerry-smith

- 10

“Jerry Smith,” Pro Football Reference, accessed 20 June, 2025,https://www.pro-football-reference.com/players/S/SmitJe01.htm

- 11

Zach Selby, “Instant analysis | McLaurin sets franchise record, gets Commanders' 12th win with 4th-quarter TD,” Official Site of the Washington Commanders, 5 January, 2025. https://www.commanders.com/news/instant-analysis-mclaurin-sets-franchise-record-gets-commanders-12th-win-with-4th-quarter-td

- 12

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 13

Scott Allen, “Washington’s Jerry Smith among those who paved the way for Carl Nassib’s coming out as gay,” The Washington Post, 24 June, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/06/24/jerry-smith-sister-carl-nassib/

- 14

Hannah Lichtenstein, “'A team guy right to the end': Reflecting on the legacy of Washington Legend Jerry Smith ahead of Pride Night Out,” Official Site of the Washington Commanders, 20 September, 2022. https://www.commanders.com/news/reflecting-on-the-legacy-of-washington-legend-jerry-smith

- 15

Tom Birschbach, “He’s Still Fighting for Player Rights : Football: Owens, former Fullerton quarterback who had stellar career with Redskins, is now an agent,” Los Angeles Times, 13 July, 1992. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-07-13-sp-3870-story.html

- 16

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 17

“1969 Washington Redskins Rosters, Stats, Schedule, Team Draftees,” Pro Football Reference, accessed 20 June, 2025, https://www.pro-football-reference.com/teams/was/1969.htm

- 18

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 19

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 20

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 21

Robert Lipsyte, “For Gays in Team Sports, Still a Deafening Silence,” The New York Times, 7 September, 1997. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/09/07/sports/for-gays-in-team-sports-still-a-deafening-silence.html

- 22

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 23

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 24

Lynn Rosellini, “The Double Life Of a ‘Bisexual’ Pro Football Star,” Washington Star, December, 1975.

- 25

Seth Abramovitch, The Hollywood Reporter, 17 July, 2014. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/nfls-first-gay-star-michael-718556/

- 26

David Kopay, The David Kopay Story: An Extraordinary Self-Revelation (Arbor House Pub 1977).

- 27

Jerry Smith: NFL Star Living a Double Life | A Football Life (21 January, 2014: NFL Films). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SlSB2gzvpBg

- 28

George Solomon, “Ex-Redskin Jerry Smith Says He's Battling AIDS,” The Washington Post, 25 August, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/08/26/ex-redskin-jerry-smith-says-hes-battling-aids/dae98b5e-1111-4b7e-9c2d-68cd68a8c0d2/

- 29

Hannah Lichtenstein, “'A team guy right to the end': Reflecting on the legacy of Washington Legend Jerry Smith ahead of Pride Night Out,” Official Site of the Washington Commanders, 20 September, 2022. https://www.commanders.com/news/reflecting-on-the-legacy-of-washington-legend-jerry-smith

- 30

George Solomon, “Ex-Redskin Jerry Smith Says He's Battling AIDS,” The Washington Post, 25 August, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/08/26/ex-redskin-jerry-smith-says-hes-battling-aids/dae98b5e-1111-4b7e-9c2d-68cd68a8c0d2/

- 31

Christine Brennan, “Family, Friends Gather For Jerry Smith Funeral,” The Washington Post, 21 October, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1986/10/22/family-friends-gather-for-jerry-smith-funeral/4c1b79a5-8beb-43f3-a1c1-615ac1612cd9/

- 32

Christine Brennan, “Family, Friends Gather For Jerry Smith Funeral,” The Washington Post, 21 October, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1986/10/22/family-friends-gather-for-jerry-smith-funeral/4c1b79a5-8beb-43f3-a1c1-615ac1612cd9/

- 33

Christine Brennan, “Family, Friends Gather For Jerry Smith Funeral,” The Washington Post, 21 October, 1986. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1986/10/22/family-friends-gather-for-jerry-smith-funeral/4c1b79a5-8beb-43f3-a1c1-615ac1612cd9/

- 34

“The shame of it Hall: Ignoring the Washington Redskins' Jerry Smith,” Fox Sports, 30 January, 2014. https://www.foxsports.com/stories/nfl/the-shame-of-it-hall-ignoring-the-washington-redskins-jerry-smith

- 35

Scott Allen, “Washington’s Jerry Smith among those who paved the way for Carl Nassib’s coming out as gay,” The Washington Post, 24 June, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/sports/2021/06/24/jerry-smith-sister-carl-nassib/

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)