The Mystery of the Antietam Arm

The legend goes something like this: two weeks after the battle of Antietam, a farmer tills his field. He might be looking for remnants of the battle: bullets, bones, or guns. He may be cleaning up his property after the soldiers have finally departed. In the plowed earth, what he finds is a human arm.

In panic, or fascination, or excitement, the man takes the arm home with him. He grabs what tools he has: some meat-curing salt from his kitchen and a wooden barrel, and then submerges the arm in a homemade brine. After a few months, the man concludes that he should get rid of it, and so gives the arm to John Mutius Gaines, a local doctor.1

Dr. Gaines, according to the legend, uses a new method of preservation, a scientific marvel—formaldehyde—and sets the embalmed arm aside in an attic. Several murky decades later, the arm sits on a display shelf in Sharpsburg, Maryland. That museum closes in 2004, and after a few more exchanges, the arm is donated, along with its local lore, to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick. 2

But just how much of this story is true?

Nobody seems to doubt that this arm came from a soldier at the battle of Antietam.3 September 17, 1862 was the bloodiest day of the American Civil War: over 3,600 soldiers died and over 17,000 were wounded.4 Among those who survived, many had to experience grueling physical recovery.

“[The arm] was traumatically separated from its owner under terrible circumstances,” said museum director George Wunderlich.

Museum curator Lori Eggleston agreed. “It is apparent […] that the arm was blown off, not amputated.”5

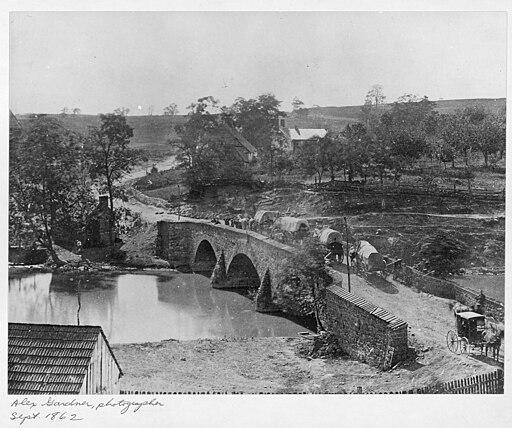

The physical evidence supports the local legend – but only up to a point. From what scholars have been able to gather, the arm wasn’t recovered near a medical tent. “According to several sources, the arm was found either on a stone wall or on a stony outcropping on the Antietam Battlefield…The Burnside Bridge is cited as the place of discovery in several of the versions.”6

Of equal importance to its separation is how the arm was treated after its recovery. The skin is well preserved, and a few hairs are even visible on its surface. “The nail beds are still so clear that they give the impression of fingernails,” wrote Eggleston. “It seems that when the arm was displayed at another museum several years ago, some people speculated that it was Confederate because of its ‘nice manicure!’”7

Could this remarkable preservation be the work of formaldehyde?

“The ‘formaldehyde’ supposedly used by the doctor was not the same compound we know today. It probably contained arsenic or mercury, which were used in embalming at the time.”8

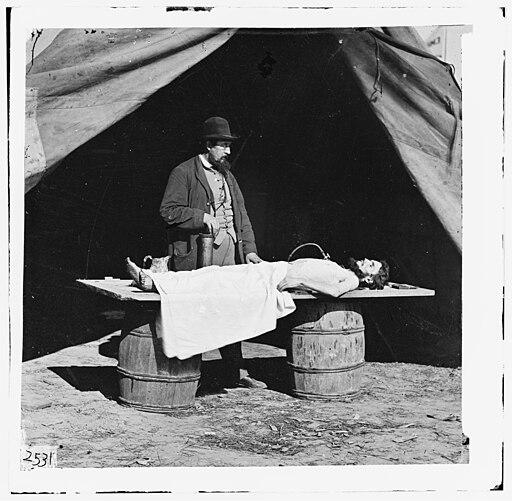

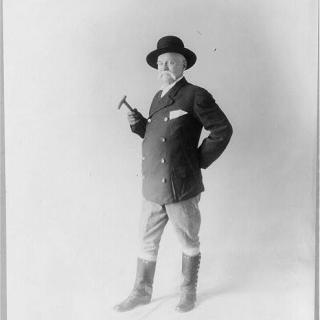

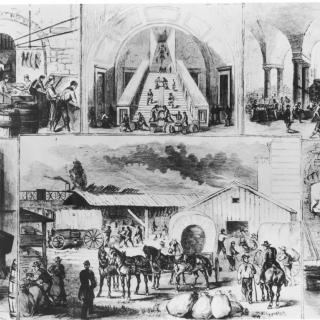

Embalming boomed during the Civil War. The process was developed in 1838, but the American “craze” really began in 1861, when the “Father of Modern Embalming,” Thomas Holmes, performed the procedure on the body of Union colonel Elmer Ellsworth. The massive scale of lives lost in the War was previously unknown to many Americans, and as soldiers fought far from home, embalming became a way for families to see their deceased loved ones before burial.9

One of the most consequential and poignant funerals of the era, the 180-city, multi-week tour of Abraham Lincoln’s body, cemented embalming as a tenant of American mourning culture. Thousands of Americans visited the president’s casket.10 But Lincoln’s high-profile funeral march revealed something which family-buried soldiers did not. Formaldehyde embalming doesn’t last.

“By the time the funeral train got to New York, the discoloration was evident, with viewers describing [Lincoln’s face] either as ‘wan and shrunken’ or ‘shrunken and dark.'”11

Preservation technology, although evolving, could only do so much in the 1860s. For the Antietam Arm, homemade embalming was an unlikely source for its remarkable preservation.

When the arm was anonymously donated to the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in 2012, curator Lori Eggleston detailed the process from reception to display on her blog. “The museum received a very interesting donation last week – the mummified forearm of a Civil War soldier!” Eggleston wrote in February of that year. “I always ask for as much history as the donor can furnish for donated artifacts, and this fellow has quite a story!”12

Eggleston sought the help of forensic anthropologists at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. Smithsonian scientists Doug Owsley and Kari Bruwelheide undertook a years-long study of the arm while Eggleston worked through the paper trail.

She discovered that John Gaines’ possession of the arm was possible, but the timeline was all wrong. “Dr. Gaines was supposedly given this arm about 6-7 months after the Battle of Antietam. That would be sometime in the spring of 1863,” Eggleston surmised. But unfortunately, “Dr. Gaines was not practicing in the area until 1866.”13

In November of 2014, the Smithsonian finally returned its findings. Strangely, “the X-ray diffraction results showed no evidence of intentional preservation using any sort of chemicals (no salts, mercury, arsenic, or lead).”14

So, if the arm had not been treated with chemicals, what explains its remarkable preservation?

The researchers were able to identify more about the arm’s former life: the soldier was male, and according to a carbon isotope analysis of his diet, he likely hailed from the Ohio River Valley, and so was probably a Union soldier. He was also unexpectedly young: only 16 to 18 years old. He stood at just 5’2” and was thin.15

Crucially, he was exhausted.

“Given the young age of the individual, and the documented health and living conditions of Civil War soldiers, it is almost certain that if this arm was from a soldier the individual would have been lean and possibly dehydrated going into battle,” explains a video from the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. “This would have been normal during the war and that condition would facilitate rapid mummification.”16

It wasn't the new medical embalming process or old-fashioned brine that preserved the arm. It was the exhaustion and dehydration that its owner, a frail teenage boy, experienced in the hours before he lost it.

“I would imagine that the soldier did not survive,” reflected Eggleston. “It is a rather sobering thought, and one that I keep very much in mind when I am handling the arm.”17

The scientific analysis was a big step forward in understanding how the Antietam Arm was so well preserved, although the exact chain of events by which it ended up in a Frederick, Maryland museum remains a mystery. Eggleston and her colleagues were unable to confirm the identity of the people who discovered it, farmer or otherwise. But the arm’s unknown story now drives the fascination—and hopefully, the compassion—of museum visitors.

“It’s not here as a curiosity,” said Museum director George Wunderlich. “Behind every number, behind every statistic, killed, wounded, or missing, there’s a human person, a personality just like you and just like me. Coming and seeing this will help you understand the true human cost of the American Civil War.”18

Footnotes

- 1

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Update on the Mummified Arm.” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), October 11, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/10/update-on-mummified-arm.html.

- 2

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Doesn’t Every Museum Need a Mummy?” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), February 2, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/02/doesnt-every-museumneed-mummy.html.

- 3

LaRocca, Lauren. “‘The Arm of the Unknown Soldier.’” The Frederick News-Post, October 30, 2014. https://www.fredericknewspost.com/news/arts_and_entertainment/the-arm-of-the-unknown-soldier/article_74f97985-b615-544f-87e3-b2182cf728fc.html.

- 4

National Parks Service. “Antietam Casualties,” January 3, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/casualties.htm.

- 5

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Doesn’t Every Museum Need a Mummy?” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), February 2, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/02/doesnt-every-museumneed-mummy.html.

- 6

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: The Antietam Arm on Display.” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), November 5, 2014. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-antietam-arm-on-display.html.

- 7

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: The Antietam Arm on Display.” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), November 5, 2014. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-antietam-arm-on-display.html.

- 8

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Doesn’t Every Museum Need a Mummy?” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), February 2, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/02/doesnt-every-museumneed-mummy.html.

- 9

Price, David. “Embalming and the Civil War.” National Museum of Civil War Medicine, February 20, 2016. https://www.civilwarmed.org/embalming1/.

- 10

Barbash, Fred. “Lincoln’s Corpse and Its Grand yet Ghoulish Odyssey.” Washington Post, October 25, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/04/17/the-grand-yet-ghoulish-odyssey-of-abraham-lincolns-corpse/.

- 11

Barbash, Fred. “Lincoln’s Corpse and Its Grand yet Ghoulish Odyssey.” Washington Post, October 25, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/04/17/the-grand-yet-ghoulish-odyssey-of-abraham-lincolns-corpse/.

- 12

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Doesn’t Every Museum Need a Mummy?” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), February 2, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/02/doesnt-every-museumneed-mummy.html.

- 13

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: The Antietam Arm on Display.” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), November 5, 2014. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-antietam-arm-on-display.html.

- 14

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Update on the Mummified Arm.” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), October 11, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/10/update-on-mummified-arm.html.

- 15

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: The Antietam Arm on Display.” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), November 5, 2014. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2014/11/the-antietam-arm-on-display.html.

- 16

Revealed - Antietam Arm, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bu7Ikr4K1lM.

- 17

Eggleston, Lori. “Guardian of the Artifacts: Doesn’t Every Museum Need a Mummy?” Guardian of the Artifacts (blog), February 2, 2012. https://guardianoftheartifacts.blogspot.com/2012/02/doesnt-every-museumneed-mummy.html.

- 18

[1] Artifact - The Antietam Arm, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XojmSSAN0lo

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)