A Monumental First: How a Small Maryland Town Built the First Washington Monument

On December 14th, 1799, George Washington died at Mount Vernon, his home in Virginia. Having served as the first President of the newly-formed United States, Washington's death plunged the country into decades of national mourning. Yet what also came out of Washington's death was his public enshrinement.

Many sought to memorialize Washington through architecture, and countless monuments popped up across the country. Locally, those included the Washington Monument in D.C. (of course!), and Arlington House, a private home in Arlington, Virginia, which was built by Washington's adopted grandson George Washington Parke Custis and his slaves, and operated like a shrine to our first president. However, 62 miles from the District is what is regarded as the nation's first true Washington Monument to be completed. Perched high atop South Mountain in a small town in Maryland, the Boonsboro Washington Monument reveals a story of patriotism, innovation and perseverance.

For the citizens of Boonsboro, Maryland, the morning of July 4th, 1827 was an exciting day. Boonsboro had long been a patriotic town, and many of its 500 citizens had been “specially venerated” by George Washington.1 What better way to honor him, they thought, than by building a permanent marker to him for all to see. As the Hagerstown Torch-Light reported, “Pursuant to previous arrangements, the citizens of Boonsboro’ assembled at the public square on the 4th instant, at half past seven o'clock in the morning, to ascend the ‘Blue Rocks,’ for the patriotic purpose of erecting a monument.”2 Trudging up the rocky, tree-laden hillside of South Mountain, the citizens began by selecting a plot of land at the very top of the mountain. Originally called “The Blue Rock”, this summit stands 1,550 feet above the town of Boonsboro and offers a fantastic view. As Thomas J. Scharf wrote in his 1882 book The History of Western Maryland “The ‘Blue Rocks’ upon which the ‘monument’ was reared…consist of immense quantities of loose rock, ranging in size from a pound to many tons, and are scattered over the top and down the slope of the mountain in confused masses.”3 These large stones and boulders were perfect to build a tower.

The building process began at a fast pace and according to the Torch-Light, “All except a few accidental visitors from the adjoining county (who ate and drank, but stood aloof from the work) seemed influenced by a vigorous principle of emulation that promised a speedy termination of that day’s labor.”4 Moving large limestone boulders by hand, the builders “seemed actuated by a spirit of zeal and ardor almost bordering on enthusiasm.”5 By one o’clock, the structure was halfway complete, and the group broke for lunch. Although “no sumptuous arrangements had been made, neither were toasts prepared for the occasion,” the citizens of Boonsboro’s “thoughts and food were both highly spiced with the contemplation of our work, thereby needing no stimulants to excite an artificial appetite.”6

When the work was finished around four o’clock, “the Declaration of Independence was read from one of the steps of the monument, preceded by some prefatory observations, after which several salutes of infantry were fired, when we all returned to town in good order.”7 After just a single day’s work, the once barren summit of South Mountain was adorned with a 15 foot tall stone tower. Soon after, citizens added a marble slab that read “Erected in memory of Washington, July 4, 1827, by the citizens of Boonsboro.” It was truly a sight to behold. However, the monument wasn't quite finished. Two months later, a smaller group returned and added another 15 feet to the structure. With these final additions completed, the monument now towered at 30 feet high.

Intended to resemble a Revolutionary War cannon, the Boonsboro Washington monument was celebrated as a success, although some felt it looked more like a milk bottle. Either way, the monument was seen as a town triumph... But this triumph did not last long. By the early 1860s, the structure had fallen into disrepair. Nearly all of the stones had originally been laid without mortar, and in the 33 years since they were placed, had fallen victim to gravity and severe storms. However, as the country was plunged into civil war, the crumbling tower found a new use as a Union signal station. On September 16th, 1862, one day before the Battle of Antietam, Captain Benjamin Franklin Fisher of the Union Signal Corps was directed to leave an officer “on Washington Monument,” which offered an expansive vantage point towards the battlefield.8 The signal officer was expected to “report to the battlefield any movements of the enemy in the valley.”9 The monument, even in its dilapidated state, proved to be invaluable to the war effort on September 17th and later battles.

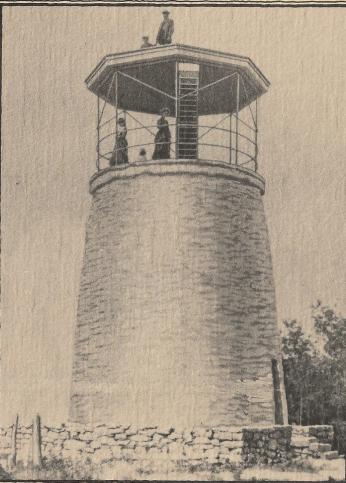

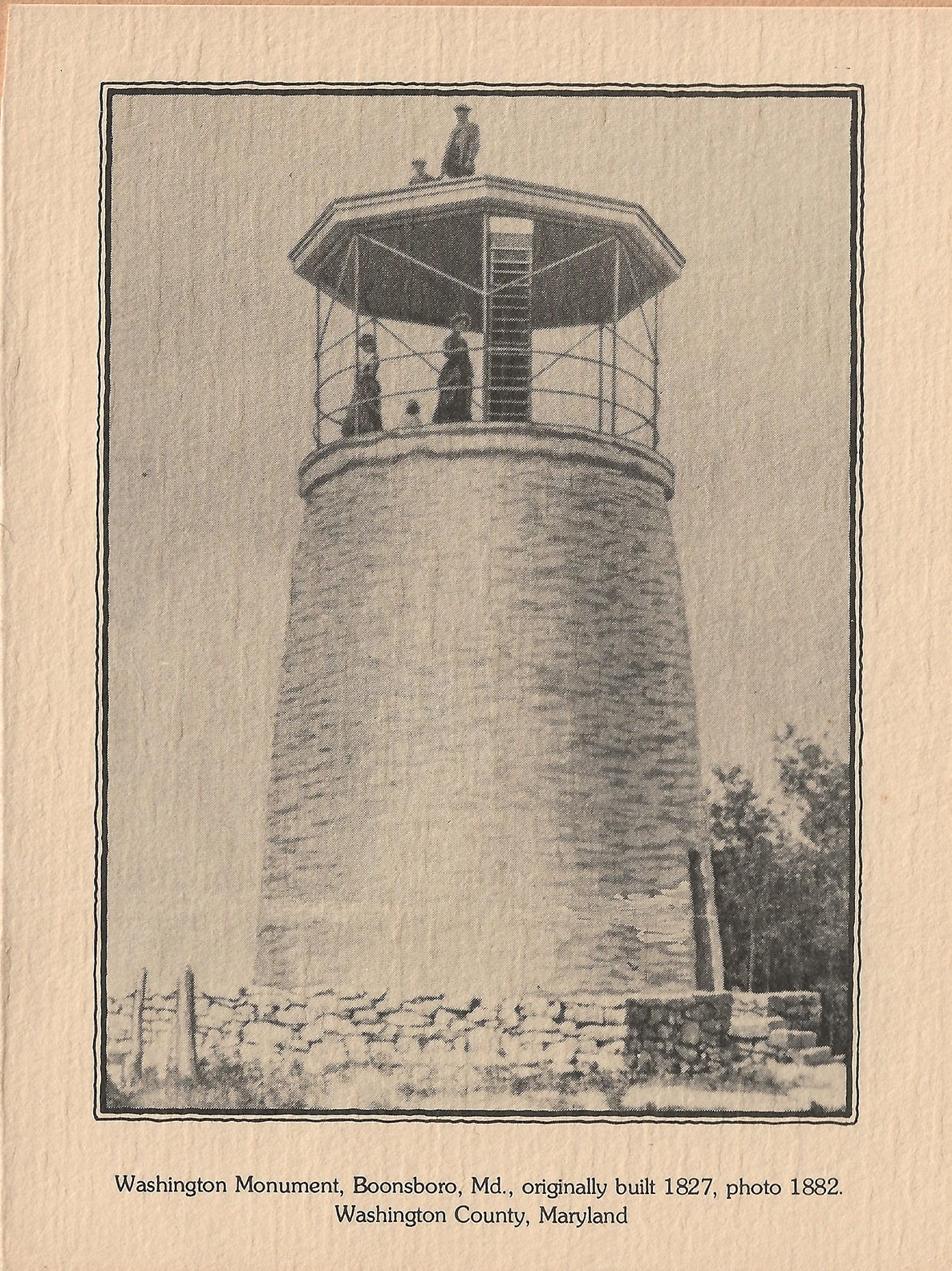

After the war, the Boonsboro Washington Monument continued to deteriorate. In 1882, however, efforts began to rebuild it. South Mountain Encampment No. 25 of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows raised funds and on August 18, 1883, a refurbished monument was officially unveiled and dedicated to “an assembly of persons from Frederick and Washington counties numbering probably 4,000 and 5,000.”10 To strengthen the structure, the new monument was designed with stucco walls and an iron observation canopy.11 While these additions were made in hopes of preventing another collapse, they also meant that the 1883 version looked very different from its original design. Unfortunately, it was mostly for naught. In September of 1896, The Washington Post reported that the monument “was either struck by lightning or dynamited a few nights ago, and badly shattered.”12 Once again in ruins, the monument would need to be rebuilt.

On January 7th, 1907, under the partial direction of Maryland Senator Harvey S. Bomberger, a longtime Boonsboro resident, the town formed the Society for the Protection and Rebuilding of the First Monument to Washington.13 Bomberger was enamored by the monument and felt that it should rightly be improved and protected. In an interview with The Evening Star in 1911, he rejected the notion that the monument was a “pile of rocks, as it has been slightingly called by those unfamiliar with it.” In his mind, it was “a memorial beautiful in its crudity and celebrated in its historical associations.”14 According to the Baltimore Sun, the society hoped “to have the United States Government place [the monument] and its surroundings in suitable and substantial condition.”15

In February of 1912, Bomberger got in contact with House Representative David John Lewis of Maryland about the monument, who introduced a bill to the 62nd House on February 6th asking for $2,500 in appropriations to restore the monument.16 One month later, Bomberger and a group of Boonsboro residents met before the House Library Committee to continue their effort pushing for federal reconstruction funds.17 The meeting apparently failed to earn support, because by 1922 Bomberger – who had become President of the Washington County Historical Society – decided the Society would purchase the land where the monument sat.18 They did, but throughout the 1920s, the nation's first monument to George Washington continued to crumble. By 1932 -- Washington's 200th birthday -- the structure was described by The Star as a “neglected and tumbled ruin.”19

Finally, in 1934, there was new hope in Boonsboro. The Historical Society deeded the monument and surrounding acreage to the State of Maryland and the Civilian Conservation Corps opened Side Camp SC-1 on South Mountain.20 Established as part of the New Deal, the CCC provided environmental conservation jobs for young, unemployed men during and after the Great Depression.

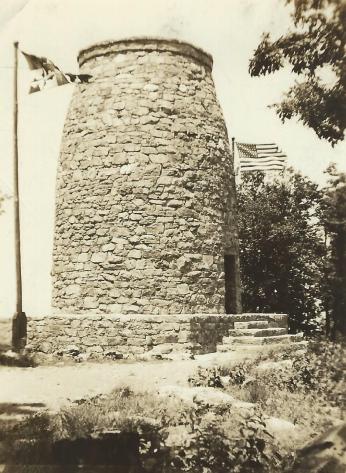

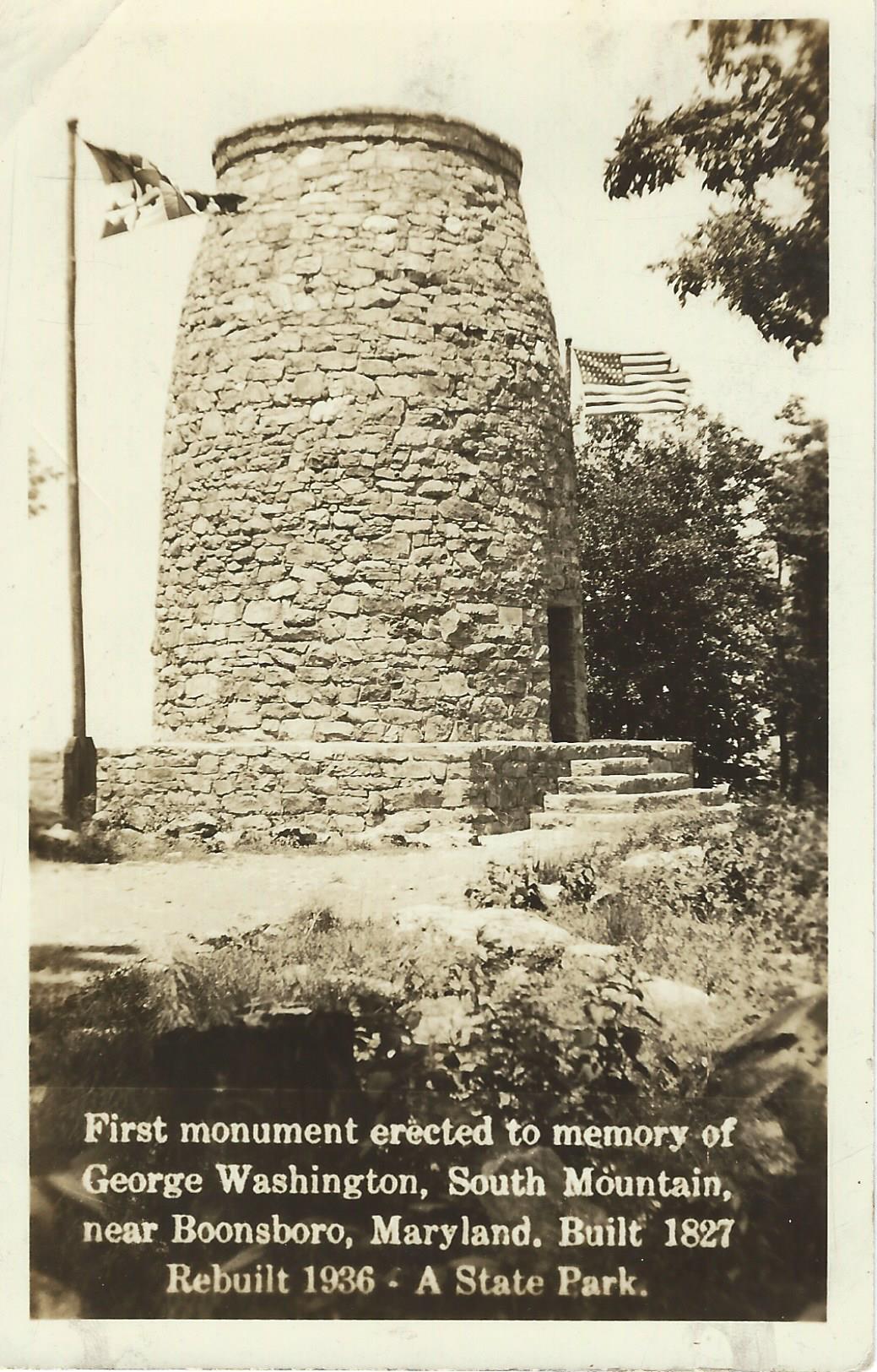

Over the next two years, CCC members on South Mountain worked to restore and rebuild the monument. Finally, on July 4th, 1936, 109 years after it was first built, the reconstructed version was dedicated in front of a crowd of thousands. It is this final version that still stands today in the appropriately named Washington Monument State Park. A short walking trail takes hikers up the very path that those 500 citizens of Boonsboro took in 1827 and still offers the expansive view that Union soldiers saw during their time at the monument in 1862.

Throughout the United States, there are countless memorials to George Washington. Some, like Mount Vernon, Arlington House, or the Washington Monuments in D.C and Baltimore, stand as well-known shrines to the first president. Yet the tiny town of Boonsboro still has the right to say it was first.

Footnotes

- 1

Scharf, J. Thomas. History Of Western Maryland V01 & V02 (Everts, 1882). http://archive.org/details/scharf-j.-thomas-history-of-western-maryland-v-01-everts-1882.

- 2

Ibid

- 3

Ibid

- 4

Ibid

- 5

Ibid

- 6

Ibid

- 7

Ibid

- 8

Brown, J. Willard (Joseph Willard). The Signal Corps, U.S.A. in the War of the Rebellion. Boston, U.S. Veteran Signal Corps Association, 1896. p.331 http://archive.org/details/signalcorpsusain00brow.

- 9

Ibid

- 10

The Sun "In Memory Of Washington: Dedication Of a Monument to The Father Of His Country in Maryland." August 20, 1883.

- 11

Parish, Preston. “Washington Monument.” National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination Form. Maryland Historic Trust, Maryland, January 31, 1972. p.8

- 12

The Washington Post. "A Monument to Washington Destroyed." September 24, 1896.

- 13

Parish, “Washington Monument.” p.9

- 14

The Evening Star, "First Washington Monument Is Threatened With Ruin" November 19, 1911.

- 15

The Baltimore Sun. "First Washington Monument: A Society To Restore The Old Structure On South Mountain." January 09, 1907.

- 16

The Baltimore Sun. "To Restore Boonsboro Shaft: Lewis Asks Appropriation For First Monument To Washington." February 07, 1912.

- 17

The Baltimore Sun. "For Boonsboro Memorial: Marylanders Will Urge Appropriation To Restore Monument." May 07, 1912.

- 18

Parish, “Washington Monument.” p.10

- 19

The Evening Star, "First Washington Monument" February 21, 1932.

- 20

Parish, “Washington Monument.” p.10

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)