Flower Power, An Exorcism, and The Resistance: The 1967 March on the Pentagon

One of the more recognizable photographs representing the Antiwar Movement and the American public’s growing dissent to the Vietnam War shows a knot of protestors confronted by Military Police. They have raised their rifles against the young student demonstrators, warding them off. But heads are turned to a young man in a chunky knit sweatshirt at the center of the photo, who holds a bunch of carnations in one hand. With the other, he threads a stem down the barrel of each soldier’s rifle, the white blooms lolling out of the guns.

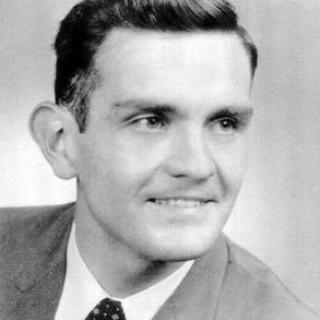

Taken by photojournalist Bernie Boston, the photo, Flower Power, is emblematic of the cultural and political friction of the 1960s, and now an iconic image of the Antiwar Movement. Initially “buried” by his editor at the Washington Star, Boston began to enter it in contests to great success; it became a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize that year.1, 2 Much later, the young protestor was identified as George Harris, founder of the drag group The Cockettes, en route to San Francisco when he stopped to protest the Vietnam War in Washington.

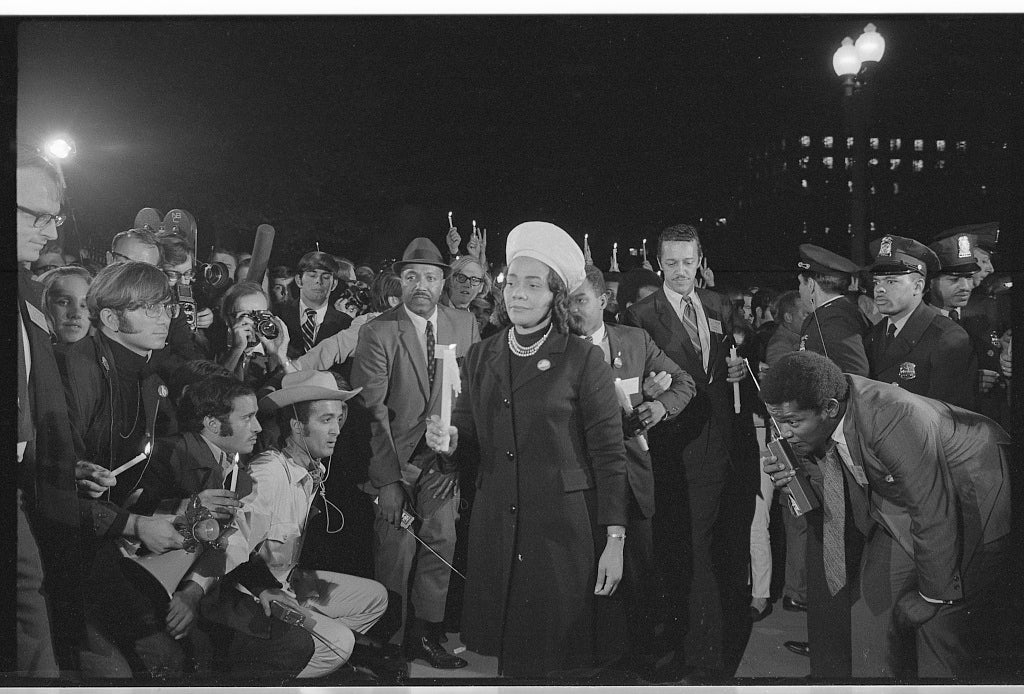

Harris, Boston, and about 100,000 demonstrators were brought together on October 21, 1967 by what was at the time one of the largest anti-war rallies ever, aiming to take demands for peace right to the steps of the Pentagon.3 In Boston’s photo, the building’s looming northern face is out of frame behind the MPs. Taken some time in the early or mid-afternoon, Boston’s photo captured the peaceful, earnest resistance of tens of thousands of demonstrators, but as the March progressed into the evening, the mood became tenser, and violence erupted.

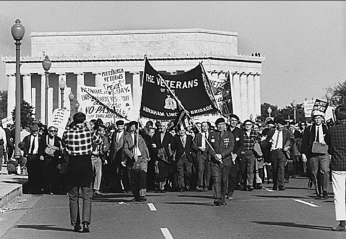

Organized by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, the demonstration initially only included a rally at the Lincoln Memorial on Saturday, October 21. However, radical writer David Dellinger and Berkeley activist Jerry Rubin dreamed up a plan they considered more effective: a march on the Pentagon, where the “real reins of power” were held.4 On Saturday afternoon, the mostly college-aged protestors would move from the Memorial across the Arlington Bridge to the Pentagon parking lot, where they would sing songs, chant slogans, wave banners, and hold teach-ins against the war into the evening.

There were “intentionally absurd” elements early on: Flower Power leader Abbie Hoffman would attempt to levitate the Pentagon with psychic energy and Tibetan chants, and musician Ed Sanders would lead an exorcism of the building. Before the protest, he called on “the demons of the Pentagon to rid themselves of the cancerous tumors of the war generals.”5 But for most protestors, the importance of the March on the Pentagon was the opportunity to take their opposition directly to the source.

Young Americans were “ready to move from protest to resistance,” demonstrator Bill Zimmerman recalled. “To us, the Pentagon was the brain of an evil monster wantonly killing innocent people half a world away and shipping young Americans home in body bags and on wheelchairs.”6

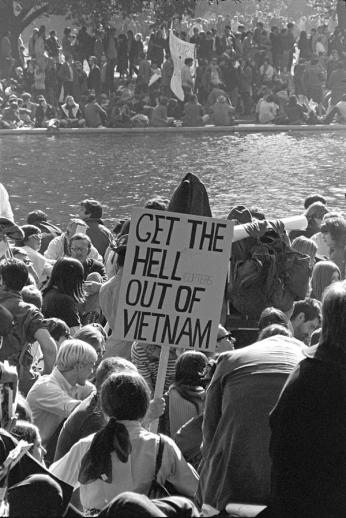

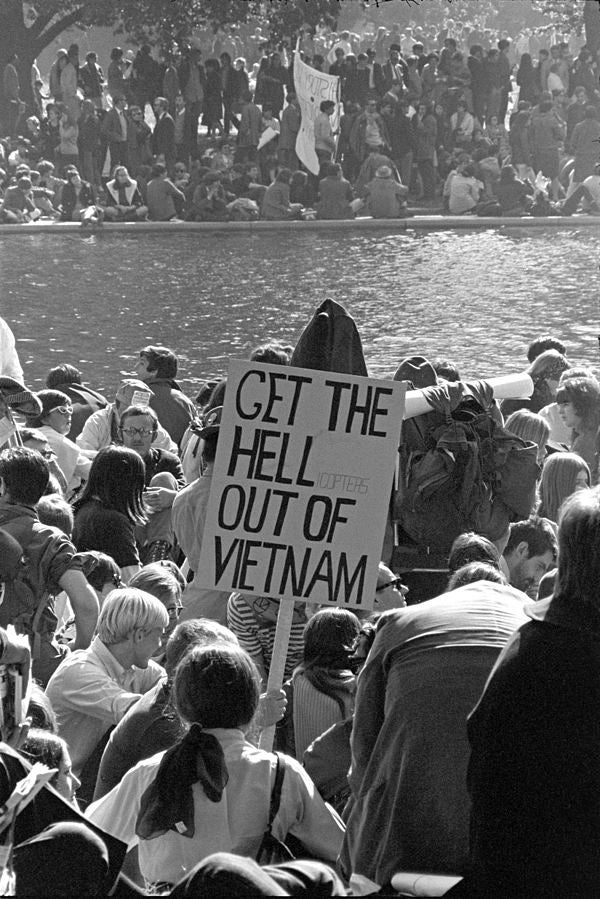

At 11:30 on Saturday morning, more than 100,000 demonstrators converged on the Lincoln Memorial, listening to speeches and a concert as “an ocean of banners and picket signs” swayed along the sides of the Reflecting Pool.7 From the long steps of the Memorial, pacifist Dr. Benjamin Spock criticized President Johnson as “a peace candidate in 1964 and who betrayed us within three months.” Dellinger, the March’s organizer, told demonstrators that the peace movement had entered “a new stage of active resistance” and that “our voices will be heard and our bodies will be hated.”8

In the late 1960s, the different strands of the Antiwar Movement had begun to coalesce into a single organized force. This was evident in the diversity of the crowd on October 21: “hippies and housewives, veterans and aging pacifists,” and tens of thousands of students. Everyone was “in a football-afternoon mood” as they waited for the sign, expected mid-afternoon, for the rally to become a march.9 Around 1:30, a few small groups began to trickle down the Arlington Memorial Bridge. But the main rally hesitated until a larger group broke away: none other than veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, volunteers who had battled fascism in Spain’s Civil War.

“Thousands first cheered and then joined them,” beginning a flow of demonstrators that did not ebb for two hours, chanting and singing all the way. “Some were of an older generation, neatly dressed and smiling, advancing arm in arm with new friends, content and secure in their beliefs, occasionally chanting in unison polite slogans urging an immediate end to the conflict,” Don Berges, covering the March for radio, recalled. “Others were young, loud and angry; a few wielded crude signs with words so profane I would not dare repeat on the air.”10

Maurice Isserman, one of the 35,000 people who marched towards the north parking lot of the Pentagon, recalled how “helicopters… whop-whop-whopped overhead, doubtless keeping close tabs for the authorities.”11

The mood of Pentagon and government officials was indeed tense. Dellinger had already threatened “acts of civil disobedience” outside the scope of the event’s permit, which allowed only vigils, pickets, and peaceful demonstration.12 All morning, soldiers had been busy “building barricades, filling sandbags, raising fences, digging trenches, rolling out communication wire, positioning troops.”13

As the marchers approached, they were met with barrier fences, 300 Deputy Marshals, military police, and “five to six thousand Army troops armed with rifles and bayonets” in the Pentagon and surrounding area.14 Snipers and federal agents were stationed on the roof of the building.

Despite the ring of armed soldiers around the building, the demonstration kicked into full swing. Allen Ginsburg began the exorcism, leading “incantations of ‘Out, demons, out!’” among the protestors. “Decked out in multicolored capes,” the rock band The Fugs provided musical accompaniment.15

Obviously, no government buildings were levitated that Saturday, but for demonstrator Trudi Schutz, the result was less important than the intent: “We wanted to raise that symbol of the war off its foundation and say yes to what we believed America stood for.”16

Unfortunately, as the afternoon went on, some protestors felt more drastic action was necessary. There was “no real plan,” of what to do at the Pentagon. The vast majority of the protesters were peaceful, but others wanted to “ransack” the building—if not levitate or exorcise it.17 Younger people especially were frustrated and angry, ready for civil disobedience or something more serious.

“Skirmishes” broke out between some protesters carrying poles “for self protection” and police; protestors began tearing down the two rows of fencing around the building.18 Thousands of mostly college-aged demonstrators were closing in on the ring of soldiers shielding the building—only to realize they were no older than themselves.

Realizing the soldiers did not have ammunition, Zimmerman and others attempted to convince them to defect to their side. “Some tried to maintain a military demeanour with stiff upper lips. There… was a lot of communication. In a few instances some talked back, gave counter-arguments, nodded and shrugged. They were confused and some of them may have been leaning against the war.”19

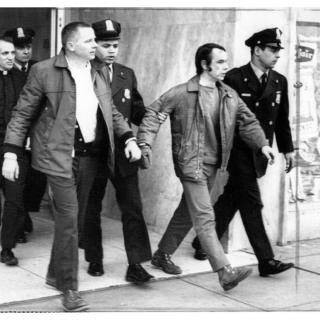

As the second fence came down, a few dozen demonstrators made a break for an unguarded door for the press. Most of them were stopped by tear gas and the Marshals’ rifle butts but about a dozen briefly made it inside. The intruders were “carried… out bodily,” the Pentagon’s floor “spotted” with blood; thousands of other protestors sang America the Beautiful.20

Though the young Army soldiers remained mostly disengaged from the rowdy demonstrators, the Deputy Marshals were not. Pat Graves, an Army soldier from nearby Fort Meyer, did not like how the “aggressive” Marshals used the soldiers as shields, “reaching between [them] to hit protestors.”21 They threw cannisters of tear gas (though this was later vehemently denied). One protestor recalled sitting “with tear gas wafting around us… [and] Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara watching us, silhouetted… on a lower Pentagon balcony.”22

One journalist reported: “When one group of soldiers was surrounded, marshals waded into the demonstrators and fists began flying. A marshal repeatedly clubbed one demonstrator, whose friends fought back with fists. Others jeered, screamed, and cursed the military.”23

Noam Chomsky, lecturing within earshot of the soldiers as part of a teach-in, watched how they put on gas masks and advanced into the crowd, arresting protestors—some peaceful, others violent. “My audience of gas masks passed by me and I kept talking to a wall of the Pentagon, which I’m sure was most responsive. Until my turn came [to be arrested].”24

It was in this atmosphere of chaos that George Harris came forward with his flowers and Bernie Boston centered him in his camera’s viewfinder.

"I saw the troops march down into the sea of people… and I was ready for it. One soldier lost his rifle. Another lost his helmet. The rest had their guns pointed out into the crowd, when all of a sudden a young hippie stepped out in front of the action with a bunch of flowers in his left hand,” Boston said in a later interview. “He came out of nowhere.”25

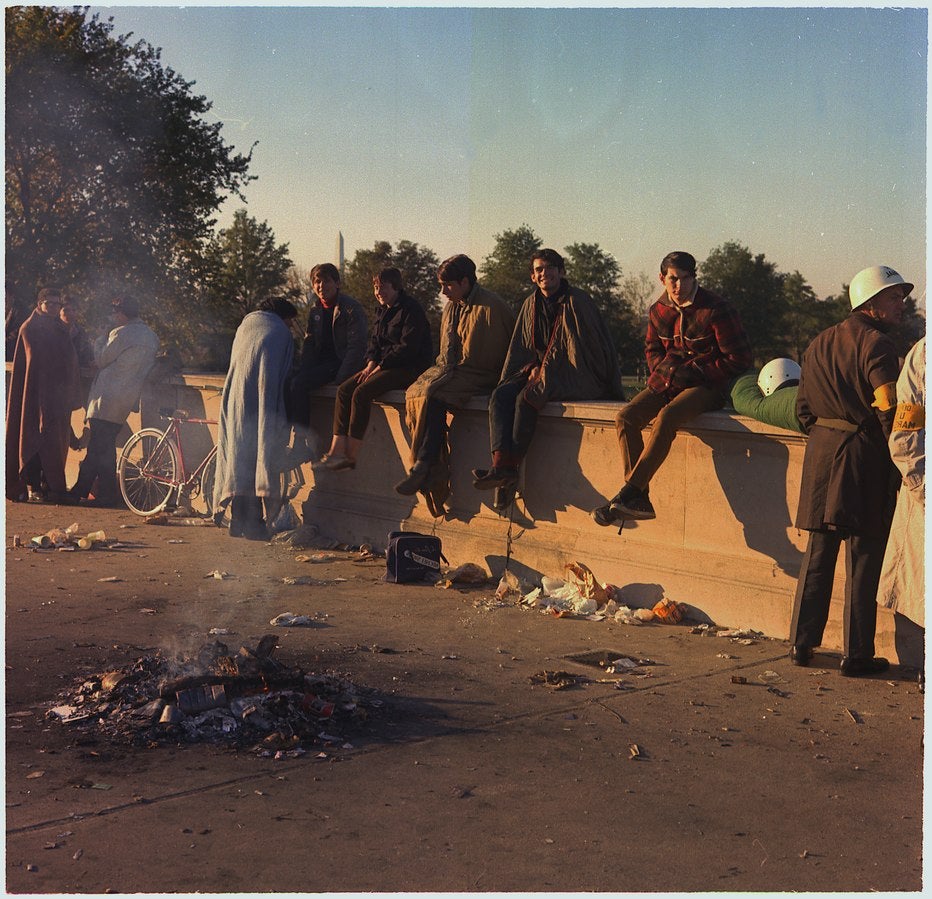

After Boston snapped his shot and left the scene (to find his car tires slashed by protestors and a bouquet of flowers under the wipers), the tense atmosphere became more combative. Older protesters were departing as the sun set and some had left at the first signs of unrest, leaving the more radical, younger demonstrators. They began “hurling insults at the soldiers and pitching rocks through the building’s windows.”26 As the temperature plunged, they burned picket signs and draft cards on bonfires to keep warm.

Around midnight, when the event’s permit expired, Marshals began to disperse protestors, “using their nightsticks to viciously attack anyone who resisted.”27 Demonstrators were beaten, chased, and arrested by the Marshals and military. One soldier recalled several Marshals pouring canteens of water downhill towards the remaining protestors, dampening their clothes and blankets.28

By dawn, the violence, cold, and stress withered the crowd “down the several hundred.”29 Organizers began a “dignified retreat” as the Marshals and soldiers pushed the remaining protesters away from the Pentagon, towards a line of idling buses.30

By Sunday morning, over 680 people had been arrested, including linguist Noam Chomsky, author Norman Mailer, and organizer Dave Dellinger. At least 47 people were injured, including soldiers and Marshals. This may be an undercount: demonstrator Nadya Williams described seeing women in a restaurant bathroom on her way home, washing “the blood off their skulls and out of their hair from the rifle-butt blows from the guards.”31

The impact of the protest was less broadly galvanizing than the organizers might have hoped. “Sustained and serious” public resistance began only in 1968, after the Tet Offensive.32 One protestor blamed the “overall weirdness” of the demonstration’s countercultural beats, which provided excuses for the media “to dismiss, ignore and discourage the participation of serious people with serious criticisms of bad government policy.”33

But for others, the sheer number of demonstrators was a victory, showing “public dislike of the war was growing rapidly.”34 Nancy Kurshan recalled children of Johnson administration officials marching alongside her. Indeed, the March on the Pentagon was a key precedent to a 500,000-strong protest in 1968 and the 1970 student strike, in which four million young people participated.35 A few days after the protest, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times wrote that the March on the Pentagon would be remembered for its redefinition of resistance, which would “move beyond dissent and yet stop short of direct violence.” However, he counselled the Antiwar Movement’s leaders to avoid more “episodes” like October 21. “Whatever their view of the war,” he wrote. “Most Americans think the Pentagon episode was enough.”36

For better or for worse, he was wrong. The Antiwar Movement, its historical significance, and its tension with Washington, was only getting started.

Footnotes

- 1

Bernstein, Adam. “Bernie Boston, 74; Took Iconic 1967 Photograph.” Washington Post, January 24, 2008. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/01/23/AR2008012303713.html.

- 2

Ashe, Alice. “Bernie Boston: View Finder.” Curio, 2005. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1033&context=curio.

- 3

The New York Times. “The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.” The New York Times, October 20, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/10/20/opinion/sunday/march-on-the-pentagon-oral-history.html.

- 4

Burns, Alexander. “The Day The Pentagon Was Supposed to Lift Off Into Space.” AmericanHeritage.com, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20051219220648/http:/www.americanheritage.com/articles/web/20051021-pentagon-vietnam-protest-washington-dc-lyndon-johnson-jerry-rubin-david-dellinger-allen-ginsberg-yippie-robert-mcnamara.shtml.

- 5

Burns, Alexander

- 6

Zimmerman, Bill. “When We Marched on the Pentagon.” Truthdig, September 30, 2017. https://www.truthdig.com/articles/when-we-marched-on-the-pentagon/.

- 7

Zimmerman, Bill.

- 8

Farrar, Fred. 1967. HURL BACK PENTAGON MOB: SOLDIERS, MARSHALS BEAT OFF PROTESTERS 30,000 IN CAPITAL ANTI-WAR MARCH; 174 ARRESTED; 30 INJURED IN WILD DEMONSTRATIONS TROOPS FIGHT MOB AT DOOR OF PENTAGON 3 MARCHERS GET IN, ARE THROWN OUT. Chicago Tribune (1963-1996), Oct 22, 1967.

- 9

Chapman, William. “Rally Against the Vietnam War at the Pentagon, 1967.” Washington Post, October 22, 1967. https://college.cengage.com/history/ayers_primary_sources/rallyagainst_vietnamwar_pentagon1967.htm.

- 10

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 11

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 12

Farrar, Fred.

- 13

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 14

Seltman, Timothy. “U.S. Marshals and the Pentagon Riot of October 21, 1967.” U.S. Marshals Service. Accessed November 3, 2024. https://www.usmarshals.gov/who-we-are/history/historical-reading-room/us-marshals-and-pentagon-riot-of-october-21-1967.

- 15

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 16

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 17

Zimmerman, Bill.

- 18

Zimmerman, Bill.

- 19

Zimmerman, Bill.

- 20

Chapman, William. “Rally Against the Vietnam War at the Pentagon, 1967.” Washington Post, October 22, 1967. https://college.cengage.com/history/ayers_primary_sources/rallyagainst_vietnamwar_pentagon1967.htm.

- 21

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 22

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 23

Chapman, William.

- 24

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 25

Ashe, Alice. “Bernie Boston: View Finder.” Curio, 2005.

- 26

Burns, Alexander. “The Day The Pentagon Was Supposed to Lift Off Into Space.” AmericanHeritage.com, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20051219220648/http:/www.americanheritage.com/articles/web/20051021-pentagon-vietnam-protest-washington-dc-lyndon-johnson-jerry-rubin-david-dellinger-allen-ginsberg-yippie-robert-mcnamara.shtml.

- 27

Zimmerman, Bill.

- 28

"The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History."

- 29

Smith, David. “How This 1967 Vietnam War Protest Carried the Seeds of American Division.” The Guardian, October 21, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/oct/21/1967-vietnam-war-protest-american-division.

- 30

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 31

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 32

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 33

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 34

“The March on the Pentagon: An Oral History.”

- 35

Smith, David. “How This 1967 Vietnam War Protest Carried the Seeds of American Division.” The Guardian, October 21, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/oct/21/1967-vietnam-war-protest-american-division.

- 36

Lerner, Max. 1967. Meaning of 'resistance' at siege of the pentagon. Los Angeles Times (1923-1995), Oct 25, 1967.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)