May 1970: College Park Explodes

The May 4, 1970, antiwar protest at Kent State University in Ohio, in which National Guard troops fired into a crowd of demonstrators protesting the Nixon Administration's invasion of Cambodia and shot four of them dead, was a traumatic event that burned itself into the American collective memory. A photo of a teenage girl crying out in shock over the body of one of the slain students became, for many, the iconic image that captured a frighteningly turbulent time.

But it's almost forgotten that the University of Maryland's flagship campus in College Park was rocked by a protest that was bigger and possibly more raucous than the one at Kent State.

Thousands of demonstrators occupied and vandalized the university's Main Administration building and ROTC offices, set fires all over the campus, and blocked Route 1, the main road into College Park. Armed with bricks, rocks and bottles, the protesters continuously skirmished with police armed with riot batons, tear gas and dogs. As the campus raged, Maryland Gov. Marvin Mandel sent in National Guard troops in an effort to quash the uprising. Fortunately, unlike Kent State, no lives were lost at College Park.

Compared to some other campuses across the nation, the University of Maryland was relatively calm throughout the 1960s. But that all changed on April 30, 1970, when President Richard Nixon appeared on all three TV networks to announce he was officially expanding the Vietnam conflict into Cambodia. In truth, the U.S. had secretly begun bombing the neutral country, which was seen as a Viet Cong sanctuary, nearly a year before, and U.S. and South Vietnamese forces already had entered the country in April. (From the PBS website, here's more background on the Cambodian war.) But Nixon's public doubling-down on the war — just 10 days after he had promised to start massive withdrawals of U.S. troops from Vietnam — stirred outrage among students.

It didn't take long for UMCP to join in the tumult. On Friday, May 1, the unrest started with a noon rally in front of McKeldin Library, with speakers attacking Nixon's decision to invade Cambodia, a neutral country in the Vietnam conflict that the Pentagon saw as a communist ally. After about 45 minutes, according to a Washington Post account, an unidentified student got up and urged the crowd to march to the General Reckord Armory, the home of the school's ROTC program. Slowly, the crowd began moving. At the armory, students broke into the room where Air Force ROTC uniforms were stored, and began throwing them out into the crowd, chanting "Rotcee must go!" Meanwhile, upstairs, other protesters broke into ROTC offices, where they overturned desks and dumped the contents of file cabinets.

By 1:15 p.m., the crowd had moved to Route 1, where they blocked traffic. About two hours later, state troopers and Prince George's County police marched into the street in formation. They wore helmets and carried batons, and had gas masks ominously attached to their belts. The crowd dispersed, and for the next 90 minutes, the two sides stared at each other warily in a standoff. Then the crowd started moving south on Route 1, and began to block a different intersection. The police chased them and broke up the roadblock again.

But, the protesters didn't go away. Instead, they broke into smaller groups and ran across the campus, deflating the tires of police cars and committing other small acts of defiance. Near campus police headquarters, officers ordered students to disperse, and when they didn't, a melee ensued in which a student government leader was knocked to the ground. He was led away by police, with blood streaming from his head.

By 8 p.m., the angry crowd had again reformed, and by the Post's estimate, numbered between 1,000 and 1,200. Additional police arrived on the scene so 250 officers were there to confront the crowd. For several hours, the two sides stood waiting. Then, by the Post's account, the students began bombarding the police with bottles, eggs, and rocks, and the officers again charged, driving the crowd back across the campus. Tear gas was fired outside a women's dormitory, and the student protesters again fled and split up into smaller contingents. Finally, by 1 a.m., the battle had subsided enough that state police Lt. Col Tom S. Smith, who was in charge of stopping the unrest, felt comfortable enough to order his forces to head back to the university police station along Route 1. Meanwhile, at Gov. Mandel's orders, two companies of the Maryland National Guard went on standby alert.

That night, about 25 people were arrested, and 50 injured. The Post called the protest "the largest and most violent in the university's history."

The situation continued to boil over the next several days. On the night of May 3, with a crowd again blocking Route 1, local police and 250 state troopers showed up and arrested six of the demonstrators, and weren't able to reopen the road to traffic until 4:45 a.m. On Monday, May 4, Mandel sent in 600 National Guardsmen to assist the police.

It didn't stop things. The next day, after a morning memorial service for the slain students at Kent State and others killed in a protest at Jackson State College, an even bigger crowd of 3,000 again blocked Route 1 in the five-block area between Ritchie Coliseum and College Avenue. According to a Post account, protesters improvised fortifications by filling trash cans with firewood stolen from Fraternity Row, doors, sawhorses, and no-parking signs ripped from their moorings. To top things off, they dragged a piece of construction equipment from campus into the middle of the road and set it on fire, sending a huge plume of black smoke into the sky. As police intelligence agents appeared on the roofs of stores, protesters pelted them with stones. Just before 5 p.m., the police, brandishing nightsticks and accompanied by K-9s that occasionally snapped at crowd members, marched into the street and cleared it. They also began firing tear gas — reportedly 100 rounds of it, so many that a stinging cloud hung over the campus, even as it began to rain. Mandel declared a state of emergency, and put a National Guard officer, Adjudant Gen. Edwin Warfield III, in "complete command" of operations on campus. That evening, as helicopters buzzed over the campus, the beefed-up force imposed a nighttime curfew. Forty-eight people were arrested, according to news reports.

When protesters showed up two days later at the ROTC armory, this time they were met by 20 National Guardsmen armed with M-16 rifles with unsheathed bayonets attached. But unlike Kent State, no shots were fired. Gen. Warfield wisely instructed his troops to keep their ammunition on their belts and told them not to load it unless he gave a direct order. According to the Post, some protesters taunted the soldiers, but others "talked quietly to them or put dandelions in their rifle barrels." By early the next morning, the crowd faded away.

Even so, the university administration clearly was spooked. They announced classes would be suspended indefinitely, starting the next day, May 8. Word of that decision enraged many faculty members, and they passed a resolution condemning it and supporting the student strike. As the Washington Post explained at the time, "The administration, in a word, had radicalized its faculty." Fearing a revolt among its own staff, the university administration backed down.

On May 11, the protesters again rose up. At 2 p.m., after a rally, about 500 of them marched to the ROTC armory and occupied the gymnasium. Then they moved to block Route 1 once again. Windows were broken, and protesters set a fire inside the Shoemaker Building on campus.

By May 12, things had calmed down enough that University of Maryland chancellor Charles E. Bishop could show up on campus and give a speech entitled "The State of the University." The Washington Post reported that on the mall, "hundreds of students were busying themselves studying, playing with Frisbees, or sleeping in the sun." But that normality was enforced by 1,100 National Guard troops who remained poised just off campus, as a deterrent to anyone who wanted to rekindle the protest.

Here's a more detailed account of the protests, written by campus radicals themselves.

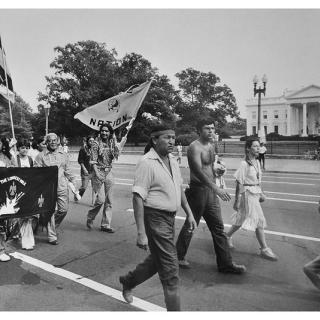

![Hundreds of draft protestors stand outside the courthouse where the trial of the Catonsville Nine takes place, peace signs up in support of the Nine. (Source: William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0025.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/street-rally-s_0.jpg?itok=E3FhlO92)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)