The Tizard Mission: The Briefcase That Changed World War II

On the morning of August 29, 1940, while the Battle of Britain[1] raged in the skies overhead, a small group of men boarded an ocean liner and left the country with the nation’s most sensitive military secrets.

These men were not spies or Nazi sympathizers. They were among the United Kingdom’s foremost civilian and military scientists, and they were headed for Washington, D.C. in an attempt to turn the tide of the war, which at that point was going very heavily in favor of Nazi Germany.

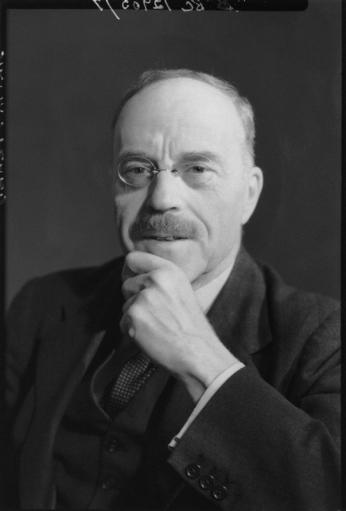

The plan, officially known as the British Technical and Scientific Mission,[2] was to share Britain’s latest military technological advances with the U.S. government in exchange for access to America’s vast industrial capacity to produce the weapons that could be yielded from the research. Unofficially, it was called the Tizard Mission, after Sir Henry Tizard, who at the time was chairman of Britain’s Aeronautical Research Committee.

Tizard was central to organizing scientists for the British war effort. He recognized the value of radar[3] and other scientific advances that could help the British gain an advantage over the powerful Nazi war machine. But by mid 1940, Britain was the only country in Europe not under Nazi occupation, and it was suffering nightly bombings that had stretched its infrastructure to the breaking point. The country simply did not have the industrial capacity to continue developing these new military projects.

Tizard proposed to the newly elected Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, that Britain could offer to exchange its technological advances, primarily its new radar system, with the Americans in exchange for mass production and return back to England.[4] Churchill and members of his staff were far from keen on giving away some of his country’s most prized military secrets, but he was desperate for America’s help in the war effort.

In the U.S., President Franklin Roosevelt wanted to provide all the help he could to Great Britain, as it was the last country keeping the Nazis from conquering all of Europe. If the British fell, prospects for an American invasion to free the continent would have faced nearly impossible odds. However, not everyone in America saw it that way. There was a very strong isolationist sentiment in 1940,[5] and this hampered Roosevelt’s ability to overtly aid the British.

Despite the misgivings of many who advised Roosevelt and Churchill, Tizard was given permission to undertake the mission and the Americans prepared for his arrival. He assembled a team of six top military scientists[6] to help him gather and transport the technical plans, manuals, and blueprints across the Atlantic. The program took place under the utmost secrecy, and the fewer people who knew about the mission, the better.

Tizard left ahead of the team on August 14, landing in Ottawa, Canada to confer with Canadian officials and assess that country’s contributions to the scientific war effort. The rest of the men left directly for Washington aboard the Duchess of Richmond. Their cargo, aside from personal effects, included an unassuming metal deed box. BBC’s Angela Hind describes the contents:

Inside lay nothing less than all Britain's military secrets. There were blueprints and circuit diagrams for rockets, explosives, superchargers, gyroscopic gunsights, submarine detection devices, self-sealing fuel tanks, and even the germs of ideas that would lead to the jet engine and the atomic bomb.

But the greatest treasure of all was the prototype of a piece of hardware called a cavity magnetron, which had been invented a few months earlier by two scientists in Birmingham.[7]

The prototype for the cavity magnetron was the most prized possession of the secret stash that the British brought across the Atlantic on that trip. It was essential to making radar systems more powerful and accurate.[8]

The journey across the Atlantic took just over a week, and was undoubtedly one of the most harrowing trips any of these men ever undertook. This was 1940, and you couldn’t just fax the documents or email them in an encrypted message. And there were no copying machines, and although a few copies of some of the documents may have existed, it wasn’t standard practice to crank out a number of copies of any sensitive documents to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. Some of the material in that metal box was one of a kind. To add to the danger, German U-Boats were engaged in unrestricted submarine warfare, and they crisscrossed the Atlantic in what was referred to as wolf packs with no other purpose than to send British ships to the bottom of the ocean.[9]

Tizard’s team gathered in Washington on September 12 with their precious cargo safely in tow. Tizard had already spent almost three weeks setting up mission headquarters at the Shoreham Hotel not too far from the British embassy. Mission HQ operated very much like an office, complete with a staff of two secretaries sent from the Canadian National Research Council and office hours between 9:00am and 6:00pm.[10] This seems a rather conspicuous arrangement for a top secret mission, but just the same team members would meet there every morning for a briefing.

The British and their American counterparts held numerous meetings to exchange blueprints and technological knowhow on radar technology. The British shared their knowledge of ground based, airborne and shipboard radar, and the U.S. gave equipment demonstrations at the Naval Research Laboratory in Anacostia.[11]

On September 19, some of the Tizard team went to the Wardman Park Hotel to meet with Dr. Alfred Loomis of the National Defense Research Committee, the American group tasked with coordinating and conducting scientific research for military application.[12] They presented Loomis with information about the cavity magnetron, which so astounded the Americans that the stage was soon set for broad-based cooperation in microwave radar production between the two countries.

Meetings with American military personnel continued, with Tizard and his team traveling back and forth from Washington to New York, New Jersey, Boston, and California to share their work with American scientists and industrial experts. They took only what they needed from the metal deed box for each specific trip, with the remainder of the documents always remaining locked up at the British embassy.

After numerous exhaustive meetings with their American counterparts, Tizard returned to England on October 8, with the first production order of magnetrons following a month later. By early 1941, individual planes were being fitted with airborne radar instruments, paving the way for Allied control of the European skies in the next couple of years.

Footnotes

- ^ The Battle of Britain, which was the German Luftwaffe’s campaign to soften Britain’s war-making ability by air, lasted through the summer and fall of 1940.

- ^ Dr. E.G. Bowen, “The Tizard Mission to the USA and Canada,” Radar World, http://www.radarworld.org/tizard.html

- ^ Scientists in Great Britain, Germany, and the U.S. had been working to perfect radar, or RAdio Detection And Ranging, for military use since World War I introduced aircraft as a weapon of war.

- ^ Adam Purple, “The Tizard Mission and the Development of Radar,” February 28, 2013, http://www.historyinanhour.com/2013/02/28/tizard-mission-radar-summary/

- ^ U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, “American Isolationism in the 1930s,” https://history.state.gov/milestones/1937-1945/american-isolationism

- ^ Bowen, “The Tizard Mission to the USA and Canada,” http://www.radarworld.org/tizard.html

- ^ Angela Hind, “Briefcase ‘that changed the world,’” BBC News, February 5, 2007, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/6331897.stm

- ^ Paul A. Redhead, “The Invention of the Cavity Magnetron and Its Introduction Into Canada and the U.S.A.,” Physics in Canada, November/December 2001, http://www.cap.ca/wyp/profiles/Redhead-Nov01.PDF

- ^ From June to October 1940, German submarines sank more than 270 Allied ships in the Atlantic, claiming thousands of lives and many millions of dollars in civilian and military goods.

- ^ David Zimmerman, “Top Secret Exchange: The Tizard Mission and the Scientific War,” McGill-Queens University Press, 1996, p. 111

- ^ The Naval Research Laboratory was founded in 1923 with the help of Thomas Edison. See “Thomas Edison’s D.C. Invention” http://blogs.weta.org/boundarystones/2015/01/27/thomas-edisons-dc-invention

- ^ E.G. Bowen, “Radar Days,” J.K. Arrowsmith, Ltd, 1987, p. 159

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)