Marion Barry and the Bus Boycott That Launched His Career

The price of public transportation in D.C. is rising and people are angry. Although this statement could accurately describe the present time, let’s turn back the clock to 1965.

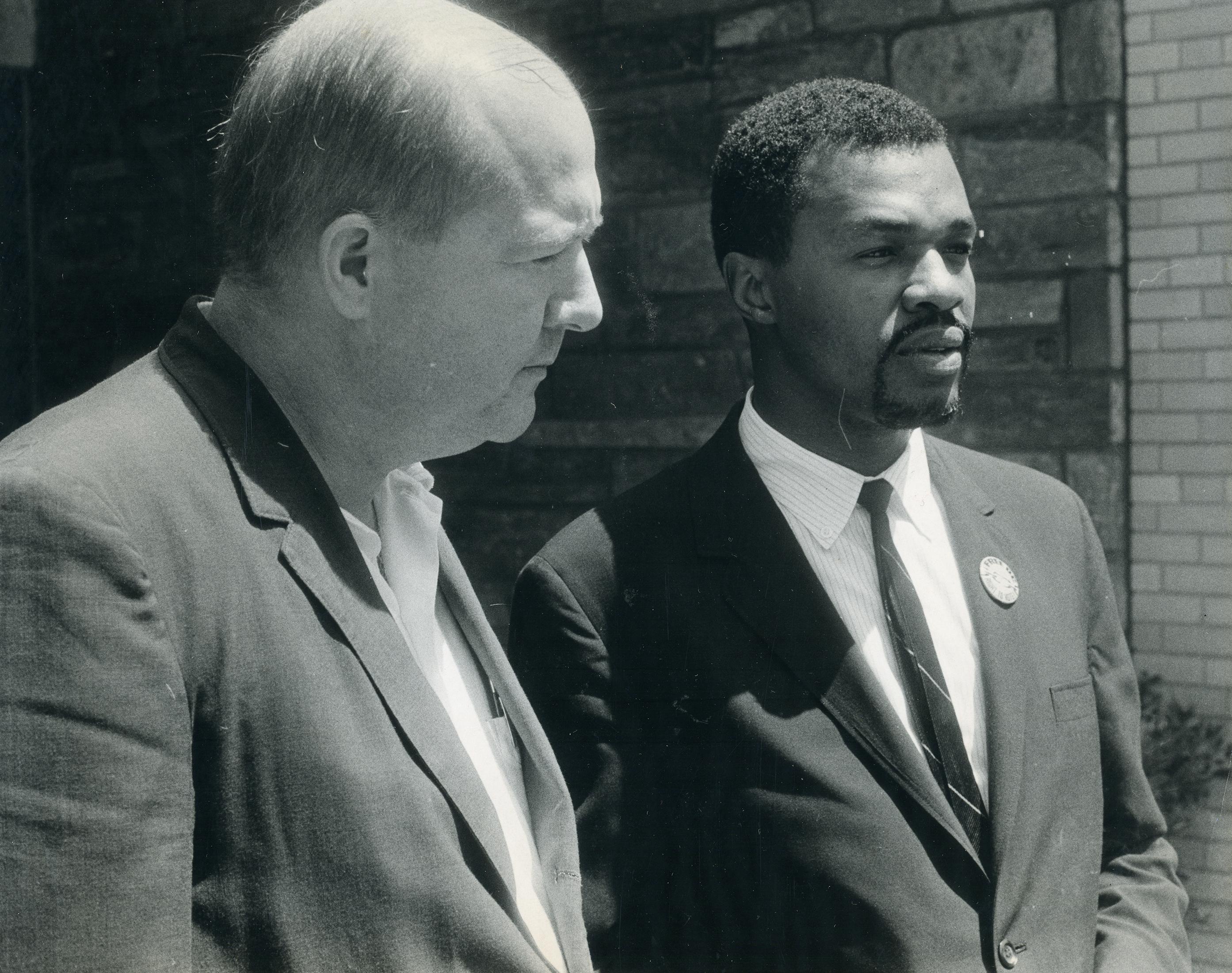

D.C. Transit had just announced plans to raise bus fares and one man wasn’t having it. This man was Marion Barry, who would go on to become mayor of D.C., serving four terms. But Barry wasn’t mayor yet. He was a relatively new resident in D.C., having moved here to open up a local chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Barry saw the bus company’s raised rates as a direct hit to low income people in the District, who were mostly African American.

On November 8, 1965, D.C. Transit appealed to the Washington Metro Area Transit Commission to increase fares from 20 cents to 25 cents a ride. The hearing was held in the Interstate Commerce Commercial Building (now one of the Environmental Protection Agency buildings) at 12th St. and Constitution Ave NW. The small room in which the meeting took place must have soon felt even smaller as uninvited guests showed up; SNCC crashed the party, bringing around 100 colleagues and associates. Speakers from SNCC made it clear that if the fare increase were to occur, a boycott would follow.[1]

SNCC was no stranger to boycotts. The organization was founded in 1960 by a group of university students, including Barry who was their first Chairman, and had been active in civil rights protests throughout the South.[2] SNCC saw the proposed fare increase as a civil rights issue because the majority of D.C. bus riders were black. One activist, Rev. William Wendt, put it bluntly: “The real issue behind this is segregation ... All they want is more white people to ride those busses.”[3] Barry added, “The bus riders are sick and tired of being exploited. They are determined to show D.C. Transit Co. that they do not want a fare increase of any kind.”[4]

A major point of contention was the premise of the fare increase. According to D.C. Transit, the added profit was needed to cover employee wages — D.C. Transit said they would have to pay employees more in 1966 than in the previous year due to the increased cost-of-living. To afford this, they needed at least an additional $150,000, according to company executives and economists they hired.

Detractors questioned D.C. Transit’s math. Edgar H. Bernstein, a former member of the D.C. Public Service Commission, maintained that “D.C. Transit’s return on investment is ‘excessive’” and that the agency “could make do with half as much.”[5] SNCC argued that D.C. Transits profits were “... an unbelievable amount of money to be making, particularly at the expense of poor people who have to ride their busses.’”[6] But D.C. Transit wasn’t swayed by the criticism, and they made it clear that they planned to raise rates no matter what. The two sides were at an impasse.

With no sign of yielding from D.C. Transit, SNCC began preparing for the boycott. Civil rights groups like Americans for Democratic Action, Congress of Racial Equality, and the Coalition of Conscience became involved, as did several churches. “If the people of Montgomery could do it, there’s no reason why we can’t,” said the director of CORE, Roena Rand, [7] referencing bus boycotts in Alabama inspired by Rosa Parks.

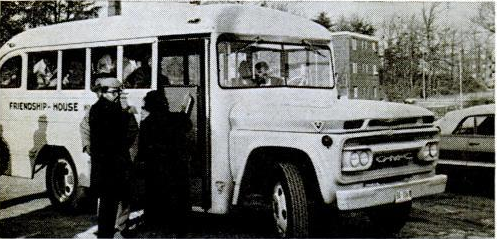

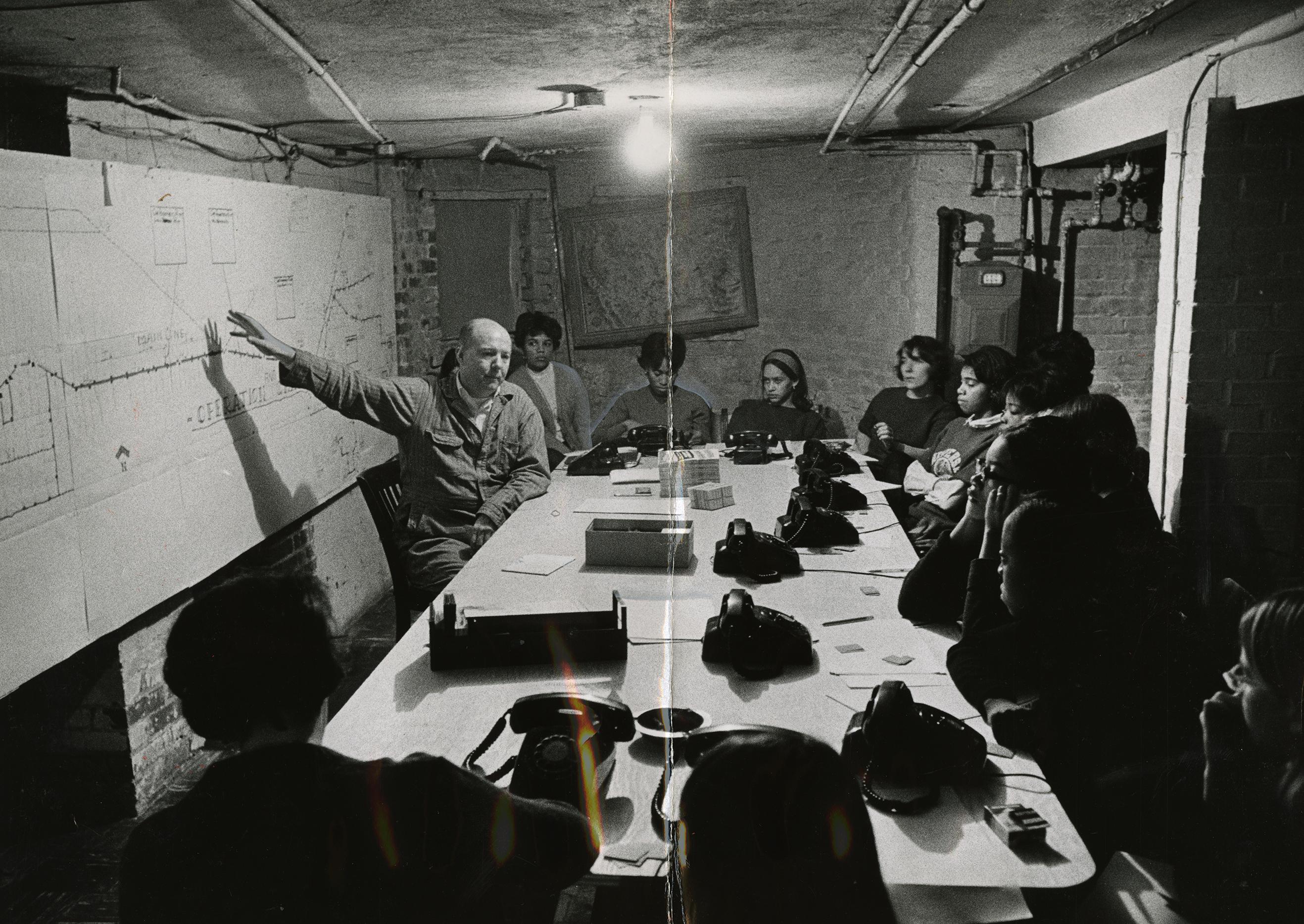

The main focus was on the Benning Road routes, which served mostly African-Americans. Organizers arranged a transportation system for boycotters: “[R]iders will be offered free volunteer car-pool and bus service to and from their jobs under an extensive plan utilizing four major car assembly points: 45 neighborhood rider substations in stores and churches; 200 volunteer cars and drivers; 20 church donated ‘freedom busses’ and more than 250 neighborhood workers” Barry explained.[8]

Volunteers who weren’t driving took on other tasks like ensuring boycotters knew where the pick-up and drop-off points for carpools were, directing drivers, and generally making sure everything ran smoothly. One newspaper article ran a story on the boycott, using the phrase, “Carefully Planned, Orderly Bus Boycott” to describe the event. “Several hundred thousand,”[9] leaflets were distributed throughout the city to inform people of the boycott, which was only scheduled to last one day because its purpose was to demonstrate the impact the community could have on the bus company if they decided to engage in a long-term boycott.

There was some public opposition to the boycott. One letter to the editor, published anonymously in The Evening Star, referred to the boycott as a “fruitless exercise.” The author went on to say that the decision to not increase fares shouldn’t rely “...on threats of boycotts. It must be made by the area transit regulatory agency solely on the basis of legal and economic realities.”[10] Washington Area Transit Commission had similar sentiments, saying in a statement, “It should be obvious that any case before the commission must be decided under the due process of law guaranteed by the Constitution.” They added that the boycott might even hurt those it was designed to help, stressing that “...any losses suffered by D.C. Transit will merely be passed on to the very transit riders who are the very people the boycott is supposed to help.”[11]

Despite these concerns, Barry and SNCC continued with their plans. The boycott would occur on January 24, 1966. That morning busses that were usually packed drove their routes and remained nearly empty.[12] One D.C. Transit representative reported that busses were being returned to headquarters because there were no riders.[13] Meanwhile, traffic was “heavier than usual” [14] and police officers were helping direct cars. Some of these cars were a part of the private car and bus system set up by the boycotters.

Journalist Sam Smith was a volunteer driver. He remembers passing empty busses throughout the day. “It’s working and it’s beautiful,” a rider said of the boycott.[15] There was a sense of community and purpose among volunteers and boycotters. One of his riders expressed her sense of disbelief at those who were not participating: “’[T]here were some of the girls at work who said they were going to ride the bus and they really made me mad. I thought I’d go get a big stick and stand at the bus stop and bop ‘em one if they got on [one of the] buses. Some people just don’t know how to cooperate. And you know, you don’t have nothing in this world until you get people together.’”[16]

Volunteers soon realized that more cars were needed. Two Howard University freshmen recounted the morning, which involved standing on a corner in the Benning Road neighborhood flagging down cars. “...within 20 minutes [they] had stopped more than a dozen cars to give rides to persons waiting there, they said.”[17]

Those involved hoped their efforts would not be in vain. One man told a newspaper, “The fare’s too high now.” Another boycotter agreed, saying “...I have to ride the bus and I can’t afford it with no regular income.”[18]

The boycott lasted all day and into the evening. An estimated 130,000 riders participated in the boycott.[19] It was “90% effective” in the Benning Road area and “40 to 45% effective throughout the city”[20] Barry said.

A side-effect of the boycott was a high absentee rate from work and school. Although the volunteer transportation system got many to and from work, apparently some were left behind. Either that or they elected to stay home. A D.C. public school reported that on the day of the boycott about six times as many students were absent than usual.[21]

Still, the boycott made a strong impression. Causing a loss of about $30,000 in a single day, it served as a harsh warning to D.C. Transit about the financial impacts a longer demonstration could have on the company. Officials backed down and the fare increase did not go into effect. Barry celebrated the victory, saying that the boycott showed “the people have power.”[22]

D.C. Transit, Co. survived seven more years before being bought out by the newly formed WMATA, or Metro, as it’s commonly called today. Marion Barry was commended for his role in leading and organizing the boycott. It helped catapult him into D.C. politics, which would lead to his eventual election as mayor.

Footnotes

- ^ Lee Flor. “Bus Fare Hearings Open With a Fight.” The Evening Star. Washington, D.C., Nov. 8, 1965, C1.

- ^ [2]"Marion S. Barry Jr. Biography." biography.com. October 1, 2015. http://www.biography.com/people/marion-s-barry-jr-9200328.

- ^ Lee Flor. “Bus Fare Hearings Open With a Fight,” C1.

- ^ “1-Day Bus Boycott Set as Fare Protest.” The Evening Star. Washington, D.C., Dec. 28, 1965, A1.

- ^ Jack Eisen. “Cost-of-Living Pay Raise Cited at Bus Hearing” The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Jan.4, 1966, C1.

- ^ Lee Flor. “Bus Fare Hearings Open With a Fight,” C1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Jack C. Landau. “Benning Road Bus Boycott Set Monday.” The Washington Post. Jan. 19, 1966, A8.

- ^ “Carefully Planned, Orderly Bus Boycott Slated By Civil Rights Group’s Leaders Tomorrow.” The Evening Star. Jan 23, 1996, D5.

- ^ “Transit Boycott.” The Evening Star. Jan. 1, 1966, B1.

- ^ “Boycott Could Backfire.” The Evening Star. Jan 21, 1966, E1.

- ^ “Carefully Planned, Orderly Bus Boycott,” D5.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Buses Hit by Fare Boycott, Benning Rd. Effect Held 90%” The Evening Star. Jan. 24, 1966, A7.

- ^ Smith, Sam. "SNCC in DC." Crmvet.org. Accessed October 22, 2015. http://www.crmvet.org/nars/sncc_dc.htm.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Buses Hit by Fare Boycott, Benning Rd.” The Evening Star, A7.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Bus Rider Loss 130,000, Boycott Leaders Say.” The Evening Star. Jan. 25, 1966, B1.

- ^ “Carefully Planned, Orderly Bus Boycott,” D5.

- ^ “Bus Rider Loss 130,000, Boycott Leaders Say.” B1.

- ^ “Fare Increase Defeat Laid to Boycott.” The Evening Star. Jan. 27, 1966, B2.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)