"The Splendid Splinter" Comes to Washington

In the winter of 1969, the Washington Senators baseball club was in transition. After a flirtation with comedian Bob Hope, the team had just been sold to transportation magnate Bob Short. Short, who looked across town and saw the Washington Redskins hire legendary coach Vince Lombardi, was looking for his own splashy hire – “a storybook manager, the kind people dream about” who could be the savior he felt the franchise needed.[1] As he said later, “Washington was not only last in terms of the American League, the sport was practically dying in the town.”[2] (Whether or not that was true is a matter of debate, but we digress.)

The new owner had one name at the top of his list: Ted Williams. Short had admired the man baseball fans called “The Splendid Splinter” from afar for years, since the Hall of Famer had been a minor league player in Minnesota. It was a long shot. Williams had twice turned down the offer to become a player-manager during his career with the Boston Red Sox. But, as Short put it, “You don’t go after anything less than divine when you’re trying to raise the dead.”[3] If he could pull off the signing, it would serve “to telegraph to everyone in the Nation that we are sick and tired of being in last place.”[4]

Williams, however, took some convincing. Then living in the Florida Keys and working as a spokesman for Sears, the retired slugger turned down Short’s initial overtures. Still, Short continued to push. “I told him I thought he had a responsibility toward the game, toward the country, toward Nixon [of whom Williams was a known to be a staunch supporter] and the whole bunch of bull you throw into a business proposition.”[5]

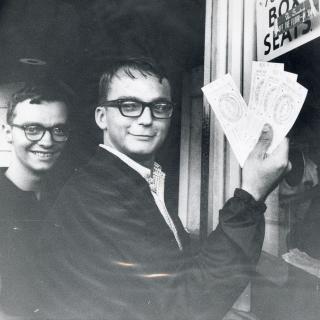

Ultimately, the recruiting pitch worked. Williams accepted the offer and signed his contract on February 21 at the Washington Hilton. It was an odd turn of events considering what he wrote in his autobiography, My Turn at Bat, which – somewhat awkwardly – came out a few months later: “All managers are losers; they are the most expendable pieces of furniture on the earth.”[6]

No doubt the sweetheart contract that Short offered played a role. Williams would be paid $65,000 per year for five years and would have the option of purchasing a 10% ownership stake in the team. It was one of the most lucrative contracts in baseball, even though Williams had never managed a game in his life.

At the press conference announcing the signing, Short laid it on thick, “This is Ted’s night, and Washington’s night, and the Senators’ night, and America’s night…. I have a world of confidence in Ted as the manager of our ball club. I know it’s traditional in baseball that great players never make great managers, but if anyone can, I believe he has the ability to become the exception.”[7] Listen to WWDC's coverage of the press conference below.

With a nod to Williams’ reputation as a prickly personality during his playing days, one reporter asked him, if he would “tolerate a player with a temperament like Ted Williams?” The new skipper’s response? “If he can hit like Ted Williams, yes.”[8]

Only time would tell, but the early returns were good. Choosing to delegate much of the defense and baserunning instruction to his coaches, Williams concentrated on what had been his forte as a player: swinging the bat.

Under Williams’ tutelage, the Senators’ team batting average jumped by 27 points over the previous season – a remarkable bump, which players (and Williams himself) attributed to the new skipper. As outfielder Frank Howard recalled, “He didn’t mess much with guys mechanically if they’d played five or ten years in the big leagues, unless they’d had absolutely no success. But he sure messed with your coconut, your mental process.”[9]

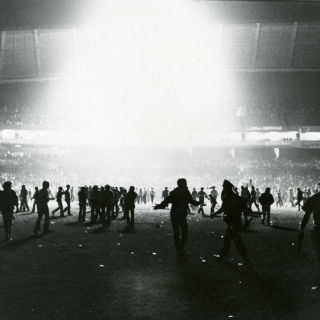

The Senators finished the 1969 season 86-76. It was good for 4th place in the American League East, which was middle-of-the-pack, but was the first season the team had finished above .500 since 1952. Washington fans were jubiliant. As Washington Post reporter George Minot Jr. wrote in his game report for the season finale, “The fans were in a carnival mood, unwilling to let go of the most successful season in memory…. They came to thank the Senators in general, and Ted Williams in particular, for bringing Washington back into the major leagues.” The rest of the baseball world took notice, too, as Williams was voted the American League Manager of the Year following the season.

According to biographer Ben Bradlee, Jr., Williams’ relationship with President Nixon was “one of the more interesting subplots of Ted’s term as manager of the Senators.”[10] Williams displayed a photo of the president prominently in his office at R.F.K. Stadium., and the Senators featured Nixon on the cover of a team program in 1970 with the caption, “Our Number 1 Fan.”

Williams and the President kept up long after both left Washington. As Nixon said in 1994 in a testimonial he recorded to celebrate the opening of the Ted Williams Museum opened in Florida, “In politics, I’ve learned that you win and you lose. When you win, you hear from everyone, and when you lose, you hear from our friends. I always heard from Ted Williams. He’s a role model. I’m one of his fans, as millions of Americans are, not just because he was a great baseball player but because he was a fine human being.”[11]

Though Williams professed confidence that his squad would improve again in 1970, it turned out that his first season was his best. As many of the players who had enjoyed career years in 1969 returned to their career norms, the team sputtered over the next several seasons. Williams struggled to keep his composure as reporters questioned his in-game decisions.

“It is bush, just plain bush!” he exclaimed after an early season loss to the Angels in his second year at the helm. “I’m going to refuse to discuss strategy with you guys if you keep on second guessing me in the papers.”[12]

Not surprisingly, the scribes had a field day. In the next day’s Post, Shirley Povich sarcastically chided “the unfeeling Washington baseball writers” as “a witless group who are without understanding that Pope Theodore II is above criticism and not to be confused with the other 23 major league managers who are subject to post-game comment and other hazards of the trade.”[13]

With wins coming less frequently, the skipper’s relationship with his players began to deteriorate, as well. Many chafed at his style, which included pointed insults, early curfews, and complaints that his players had too much sex during the season. (Williams believed that abstinence kept players sharp for games.) By the end of the 1971 season, several Senators had formed what they called the Underminers’ Club. As pitcher Denny MacLain wrote in his autobiography, “We were the people dedicated (in our minds anyway) to the overthrow of Ted Williams.”[14]

Though it didn’t work – Bob Short decided to trade most of the Underminers rather than fire his manager – Williams’ days in the dugout were numbered. After the team moved the Texas in the fall of 1971, he lasted just one more season before retiring with one year left on his contract.

The skipper’s comments about Washington after the team left town probably didn't leave the best taste in the mouths of D.C. fans.

“The American League people would have been crazy if they hadn’t allowed the shift. The way things are set up in this town—bad rent, bad concessions, no television market—hell, nobody could make it. There was a hard core of fans here all right, but there were only six or seven thousand of them. Basically. Washington is a city of transient people. Most people don’t give a damn.”[15]

Ouch. But, hey, at least we had 1969.

Footnotes

- ^ Minot, Jr., George E. “Ted Williams Meets Short In Atlanta: Fox Impresses Owner DiMaggio on List Billy Hunter Mentioned Sounded Out on Others Ted Williams Meets Short In Atlanta.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. February 13, 1969, sec. SPORTS Business/Finance/Outdoors.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., Ben. The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams. First Edition. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013, 528. Quoting The Boston Globe, March 18, 1969.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Gildea, William. “Nats’ Signing Of Williams Draws Near: Cites ‘Fear’ Problem Williams Is Symbol Safety Starts at Stadium Not a Racial Question Nats Near Accord With Williams.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. February 21, 1969.

- ^ Frommer, Frederic J., and Bob Schieffer. You Gotta Have Heart: A History of Washington Baseball from 1859 to the 2012 National League East Champions. Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2013. p. 124.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., 528.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., 531. Quoting The Boston Globe, February 22, 1969.

- ^ Gildea, William. “Nats Sign Williams to 5-Year Contract: Sought Yawkey’s Advice Expects Players’ Respect Expects Hard Work Best-Ever Pact Inked At Midnight Ted Williams Takes Helm Of Senators Ted Williams’ Playing Record.” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. February 22, 1969, sec. SPORTS / Business/Finance.

- ^ Frommer, 127.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., 547.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., 548.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., 552.

- ^ Povich, Shirley. “This Morning...” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Washington, D.C. April 30, 1970, sec. SPORTS Finance/Baseball/Racing.

- ^ Bradlee, Jr., 560.

- ^ Frommer, 137.

![Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.) Ben's Chili Bowl, 1980 (Photo Source: Library of Congress) Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Ben's Chili Bowl, Washington, D.C. United States Washington D.C, None. [Between 1980 and 2006] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011635251/. (Accessed December 04, 2017.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/17058v.jpg?itok=egZM-IR9)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)