How I.M. Pei Brought Modern Architecture to the National Mall

“Architecture is the very mirror of life. You only have to cast your eyes on buildings to feel the presence of the past, the spirit of a place; they are the reflection of society.” – I.M. Pei to Gero von Boehm for the book “Conversations with I.M. Pei: Light is the Key.”

When I.M. Pei, the celebrated Chinese-American architect from New York, was selected to design a new addition for D.C.’s National Gallery of Art, the Washington Post’s architecture critic remarked it was “no doubt one of the toughest [assignments] since Michelangelo was asked to put a dome on St. Peter’s.”[1]

Pei’s task: to devise a new building that would sit directly east of the existing museum, a neo-classical temple from the mind of architect John Russell Pope.

“He [Pei] could not possibly, in an age of space ships, just copy the Beaux Arts Classic details of the old Gallery,” Post critic Wolf Von Eckhardt wrote in July 1968 after Pei’s selection for the job. Von Eckhardt continued, “Yet the mind reels at the thought of any ‘modern’ structure adjacent to Pope’s luxurious museum.”[2]

The original museum, known today as the West Building, opened in 1941. But when the Gallery prepared to expand nearly thirty years later, planners favored a break from tradition. Paul Mellon – son of original National Gallery benefactor Andrew Mellon – virtually assured they would get just that when he selected Pei for the job.

Born in Canton, China, on April 26, 1917, today Ioeh Ming Pei is known for impressive feats of modern architecture across the globe, including the glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris, the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston and of course the National Gallery’s East Building, which for more than 40 years has housed permanent and visiting collections of modern and contemporary art. The gallery—famous for its H-shaped façade, sharp angles and open atrium—has been named one of the 10 best buildings in America.

Back in the 1970s, however, before any such accolades had arrived, some were skeptical of Pei and his plans for Washington’s preeminent art museum—including the locals. Capitol Hill staffers were sad to lose the nearby open space which housed a set of tennis courts. Others worried that Pei’s design would seem out of sorts in their city.[3]

After all, it was a tricky spot to build a modern art museum.

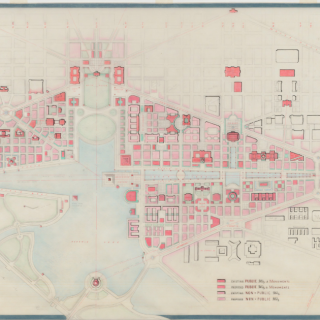

The building would, on one side, border Pennsylvania Avenue only about a half mile from the Capitol, meaning Pei’s structure would need to harmonize with both Pope’s west building and the character of the National Mall.

The plot of land itself—an awkward trapezoidal shape—posed yet another challenge. This matter, Pei would confront in an early sketch of the project by dividing the trapezoid into triangles.

“I sketched a trapezoid on the back of an envelope. I drew a diagonal line across the trapezoid and produced two triangles. That was the beginning,” Pei said.[4] One isosceles triangle holds the museum’s galleries, a smaller right triangle houses a library and offices. The wide, skylight-topped atrium links the spaces, and triangular forms become a consistent theme throughout the building.

Pei took a series of steps to visually link the east and west buildings. He tried to match the west building’s strong “east-west axis” and sought out the same stone used in the original building, reopening the same quarries in Knoxville, Tennessee.[5]

The building designs evolved over time. The atrium, for instance, became gradually more open. As of November 1970, plans called for a coffered concrete ceiling, the underside of an upper floor, to cover the atrium. Pei and his team, however, decided this would overpower the interior. They reworked the design, and by early 1971, arrived at the pattern of skylights and thin walkways that bridge each part of the space.[6]

As Pei’s plans began to take shape, there was yet another issue to consider. Washington, D.C. is a city that loves its building height codes and, sitting at the junction of Constitution Avenue and Pennsylvania Avenue, the National Gallery straddles two of them. (Constitution Avenue imposes a lower height limit than Pennsylvania Avenue.[7])

It’s no surprise, then, that the height of the proposed gallery was one of the key concerns for members of Washington’s Fine Arts Commission, which approved the design for Pei’s building in a split 4-2 verdict February 1970.[8]

Pei corresponded with commission chairman William Walton, one of the two dissenting votes:

Walton: I feel that the new building, will be a harsh, overassertive terminus to the long line of buildings leading toward the Capitol whose environs are a very touchy matter, both aesthetically and politically.

Pei: Your criticism about the excessive height of the design does not surprise me for the problem has been a matter of great concern to us from the very beginning. The final resolution, however, is the result of a great deal of deliberation.[9]

The architect had taken careful steps to ensure the building’s height would not seem out of place. The towers in the corners of the East Building would be taller than the rest of the building, which conform to the lower height limits on Constitution Avenue.[10]

Pei was certainly conscious of the challenges he faced in crafting the gallery addition, but, at the same time, believed it gave him “the opportunity to do a building that has a character of its own which unique for this site, and wouldn’t work in any other site.”[11]

After three years of planning and seven years of construction, the East Building of the National Gallery opened to the public on June 1, 1978. President Jimmy Carter accepted the museum on behalf of the nation at a dedication ceremony.

“I accept it with a full heart of gratitude to all who have had a hand in its creation and with a sense of exhilaration and joy that I know will be shared by the millions of people who will come here to look, to study, to contemplate and to be moved and delighted and ennobled by what they find here,” Carter said.[12]

“This building is the product of many minds, of many hands, all intent on giving America their best … I.M. Pei and his associates have given us an architectural masterpiece,” the president said to applause. [13]

Thousands came to the opening to explore the first exhibits on display in the east building.[14] “Finally, … the last preview party was over, the last special tour for notables, the last tune by the Marine Band, the last speech—and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art opened to the American public for which it was built,” the Post reported.[15]

While well received, the finished product did not escape criticism. Some argued it devoted too much space to the atrium and wedged the galleries—and the works of art—into the corners. “Pei was accused of upstaging the art with atmospherics,” a Pei biographer, Michael Cannell, wrote.[16]

Nevertheless, Pei managed to captivate the public and sway some of his critics. The grand opening was a “national event,” comparable to “a space launch or a presidential inauguration.”[17] Visitors flocked to experience Washington’s newest museum – it took under two months for attendance to hit 1 million.[18]

And as Cannell says, it was ironic how much people loved the east building, “at a time when ‘modernism’ had become a dirty word.” Pei is frequently lauded for improving the reputation of this style of architecture.

“More so than any other modern architect of his generation, he was able to make modern architecture friendly and approachable to a wide audience,” Cannell told the Washington Post in Pei’s obituary, “He went a long way toward translating modern architecture on behalf of a public that may not otherwise have been disposed to appreciate it.”[19]

And what about Wolf Von Eckhardt, the Post critic who had his doubts about the building throughout its years-long construction process?

It was clear he had come around to Pei’s vision, too: “Ieoh Ming Pei’s East Building of the national Gallery of Art is an architectonic symphony of light and marble, color and glass, painting and sculpture. It is surely one of the most impressive statements of the art of our time.”[20]

Footnotes

- ^ Von Eckhardt, Wolf. “History Challenges Modern Architect.” The Washington Post, 30 July 1968: B2.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cannell, Michael. “Finding the Essence.” The Washington Post, 27 Aug. 1995: N6 (excerpt of Cannell’s biography “I.M. Pei: Mandarin of Modernism, 1996)

- ^ “A Design for the East Building.” National Gallery of Art.

- ^ Ritchie, Annie G. “Interview with I.M. Pei.” National Gallery of Art Oral History Program, 22 Feb. 1993.

- ^ “A Design for the East Building.”

- ^ “An Act To Regulate the Height of Buildings in the District of Columbia.” Council of the District of Columbia, D.C. Law Library, p. 453 Washington, D.C. has a complex policy that governs building height restrictions. Part of that code says no building will exceed 130 feet on a business street or avenue, except on the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue between First and 15th Streets, where a maximum height of 160 feet is permitted. The National Gallery East Building is on Pennsylvania Avenue between 3rd and 4th Streets. Pei looked for a way to navigate this unique location.

- ^ Cannell, "Finding the Essence."

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ritchie, Annie G. “Interview with I.M. Pei.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “NGA History Timeline.” National Gallery of Art.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Kernan, Michael. “Crowds, President Carter Attend Opening of Gallery’s East Building.” The Washington Post, 2 June 1978: A1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Cannell, "Finding the Essence."

- ^ Cannell, "Finding the Essence."

- ^ “NGA History Timeline.”

- ^ Sapienza, Terri. “I.M. Pei, Preeminent Architect of Civic Centers and Cultural Institutions, Dies at 102.” The Washington Post, 16 May 2019.

- ^ Von Eckhardt, Wolf. “The Gallery’s Soaring Symphony of Light and Marble: I.M. Pei’s Geometric East Building As an Exhilarating Work of Architectural Sculpture, a Triumph Of an Art Museum.” The Washington Post, May 1978: L1

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)