"New Girl in Town": Washington Gets a Leonardo

On a cold night in February 1967, a plane landed quietly at National Airport. No one could know where it came from and what it carried. In fact, the only indication of the plane’s arrival came through a coded message, sent by the FBI agents on board: “the Bird” had landed. Despite all this, though, the only thing that came off the plane was a perfectly ordinary, plain grey American Tourister suitcase. No one suspected anything.

However, rumors circulated. Two weeks later, the New York Times broke the news that Washington’s National Gallery of Art had landed the art deal of the century: the purchase of a painting by one of the most famous artists in the world, Leonardo da Vinci.[1] Spokespeople at the Gallery could “neither confirm nor deny” the rumors, but this did nothing to quell the speculation and excitement.[2] Suddenly, the eyes of the art world rested on Washington.

The National Gallery was still young in the 1960s. Andrew Mellon—banker, Secretary of State, and avid art collector—founded the Gallery in 1937, donating his personal collection to serve as the founding works of a public, national collection. But even with Congressional backing and an impressive new building on the National Mall, the reputation of the Gallery was relatively modest in its first few decades. Though it featured paintings by notable artists, Mellon’s collection still paled in comparison to those of well-established museums, especially the other national galleries in Europe. Washington had a major art gallery, but it was still not an art capital.

The tide began to turn in 1963, when the Gallery hosted one of its first landmark exhibitions. In a stunning feat of diplomacy, First Lady Jackie Kennedy persuaded the French government to lend one of its greatest treasures to the United States: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Widely regarded as the most recognizable painting in the world, it seldom left its home at the Louvre and had never been to the United States before. On January 9, it made its “brilliant American debut” at the National Gallery, witnessed by the Kennedys, members of Congress, and ambassadors.[3] Due to the number of famous visitors, the New York Times called Mona Lisa the “temporary but undisputed queen of Washington society.”[4] In the coming weeks, Washingtonians made clear that the painting was not only famous in notable circles. Over half a million locals also came to see Mona Lisa while it was in Washington, waiting in lines for up to two hours.[5] For the first time in its history, the Gallery even had to extend its hours to accommodate the massive crowds. The Gallery director, John Walker, took note: Washingtonians had an appetite for art.

Inspired by the success of the exhibition, Walker began to show interest in acquiring new works for the collection—the more renowned, the better. Unfortunately, very few Old Master artworks were actually available for purchase; those that were sold for unfathomable prices.[6] Nevertheless, Walker began to court a piece that seemed the unattainable gem of the art world. Since Mona Lisa had drawn such an overwhelming public response, it seemed logical that the National Gallery should go after a Leonardo of its own.

At the time, the only Leonardo painting remaining in a private collection—and, therefore, potentially available for purchase—was a small, unsigned portrait from the artist’s early career. Painted around 1474, it depicts a young Florentine woman named Ginevra de’ Benci, probably on the occasion of her marriage. Leonardo painted his subject facing forward and with a serious expression, surrounded by juniper (ginepro) trees as a clever pun on her name.[7] Art historians suspect that portrait was once longer, showing Ginevra’s torso and hands, but the surviving painting only amounts to a 15 x 14” square.[8] Though generally accepted as Leonardo’s work, a lack of documentation surrounding the painting’s commission and creation allowed for some doubts. But however small and unassuming the painting seemed, and whatever the question of its legitimacy as a Leonardo, museums and collectors had been interested in acquiring it for decades. Adding a Leonardo to your collection was—and still is—a triumph, since only about twenty paintings are usually attributed to him.

Ginevra de’ Benci had long been the property of Liechtenstein’s royal family and was one of the most valuable works in their collection. Walker was “spellbound” when he first saw the painting and knew he had to have it.[9] He traveled to Vaduz, the royal seat, several times in the 60s, hoping to convince the royals to part with their treasure. “Each trip was more frustrating than the last,” he wrote in his memoirs. “The prince invariably refused to part with Ginevra.”[10] Finally, in 1966, there was a breakthrough. The royals had lost most of their vast fortune during World War II and decided to sell art to regain financial stability.[11] Walker, armed with funds provided by Mellon’s daughter Aisla Mellon Bruce, offered an amount that was “fantastically high, but since the picture is priceless, not illogical.”[12] The National Gallery has never confirmed the actual price of the painting, but the rumored $5 million was the largest amount of money ever paid for a work of art at the time.[13]

Despite their obvious excitement, Walker and the other Gallery directors were determined to keep news of the acquisition a surprise. In a secret mission that Ian Fleming might have dreamed up, they dispatched two members of their staff to retrieve the painting from Liechtenstein: Secretary-Treasurer Ernest R. Feidler, to sign the paperwork, and art expert Mario Modestini, to confirm the painting’s authenticity and manage the transportation. In order to detract attention from their overseas trip, the pair booked seats on commercial flights. They also oversaw the construction of a special suitcase—outwardly normal, but designed to carry a 500-year-old painting safely. Feidler later told the press that the case was “outfitted like a thermos jug,” with layers of plastic and Styrofoam protecting the painting from movements and bumps.[14] The case also had a specially-designed luggage tag that gave discreet readings of interior temperature and humidity, allowing Ginevra’s caretakers to monitor any dangerous changes. When Feidler and Modestini took their seats on the flight from Zurich to JFK and placed the Ginevra suitcase in the window seat, “nobody on the plane gave [them] a second look.”[15] In fact, her seat had been reserved for her—Ginevra de’ Benci traveled to the United States as an official passenger, “Mrs. Modestini.”[16]

But the mission to keep Ginevra a secret ultimately failed. On February 20, 1967, the day after the New York Times reported the purchase, the Gallery issued a press release confirming the rumored news: “Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci has been acquired by the National Gallery of Art.”[17] As the Gallery was forced to announce the news sooner than expected, the painting was not yet ready for viewing. A formal unveiling and celebration were planned for March 17, the thirtieth anniversary of the Gallery’s founding. In the meantime, Ginevra’s face graced the front pages of all the local newspapers. The Washington Post dubbed her the “New Girl in Town.”[18]

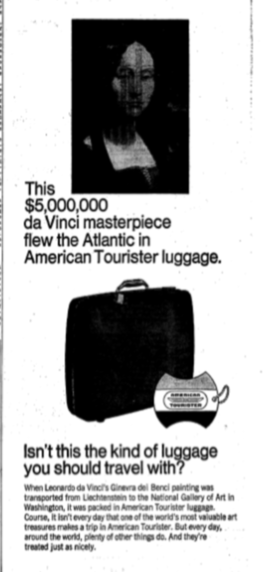

At first, the Gallery worried about the local reaction to such an expensive acquisition. Though purchased with private funds, the painting’s price tag was astonishing and unprecedented. In the late 60s, as the Vietnam War carried on and citizens staged protests against poverty and civil rights violations, such a purchase seemed luxurious and superfluous.[19] In one letter to the Post editor, Anne Sue Hirshorn lamented that “it is a little mad for any one or institution to pay $5 million for a single art object, regardless of who did it or how well.”[20] Yet the majority of Washingtonians were fascinated by Ginevra, this renowned and expensive piece of artwork skillfully acquired by their local gallery. On the first day of public viewing, the painting attracted 4,427 visitors.[21] Local schoolchildren at Gibbs Elementary School visited and then studied the painting, hosting a mock exhibit in which Ginevra, “as might be expected,” was the featured work.[22] News of its dramatic journey to Washington made national news and even inspired an American Tourister advertisement. “This $5,000,000 da Vinci masterpiece flew the Atlantic in American Tourister luggage,” it bragged. “Isn’t this the kind of luggage you should travel with?”[23]

Perhaps the best, most succinct local reaction came from a Post columnist, writing for the paper’s March 20 edition. “It is exceedingly pleasant to know that there is one field in which Washington’s institutions can and do win the big ones,” they wrote. “The Senators don’t come close. The Redskins are trying hard but aren’t even No. 2…but the National Gallery of Art is making a habit of winning the big ones.”[24] With Washington now home to a famous and respected collection, “one must begin to believe that soon we shall have on the Mall…the finest permanent collection of art and sculpture in the world.”[25] In one shrewd move, the National Gallery put itself on the art map, on par with the Louvre and London’s National Gallery.

Though the Gallery has expanded greatly over the years and is now one of the world’s foremost art museums, Ginevra de’ Benci is still the star of its collection. Washingtonians have come to take her for granted, since her fifteen minutes of fame is long past. But we should really take pride: our Leonardo is still the only one of his paintings permanently located in the Western Hemisphere. People are flocking to Paris to see the Louvre’s major Leonardo exhibit before it closes, but all we have to do is take the Metro to the Mall.

You can visit Ginevra in the National Gallery of Art’s West Building: Main Floor, Gallery 6.

Footnotes

- ^ Milton Esterow, “Leonardo Oil Brings $5-Million: National Gallery to Buy Work from Liechtenstein,” The New York Times, February 19, 1967.

- ^ “Gallery Set to Reveal $5 Million Purchase,” The Washington Post, February 20, 1967.

- ^ Marjorie Hunter, “President Attends Debut of Mona Lisa,” The New York Times, January 9, 1963.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Mona Lisa’s Visitors Get Longer Day,” The Washington Post, January 17, 1963.

- ^ Neil Harris, Capital Culture: J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2013), 69.

- ^ National Gallery of Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2008), 20.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John Walker, Self-Portrait with Donors: Confessions of an Art Collector (Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1974), 49.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Nancy H. Yeide, “In Depth: Provenance Study: The Princely Collections of Liechtenstein,” National Gallery of Art, https://www.nga.gov/research/in-depth/provenance-study-princely-collections-liechtenstein.html

- ^ Walker, 50.

- ^ Esterow, “Leonardo Oil Brings $5-Million: National Gallery to Buy Work from Liechtenstein.”

- ^ John Carmody, “A $5 Million da Vinci Spans Sea in Suitcase,” The Washington Post, February 21, 1967.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Harris, 80.

- ^ National Gallery of Art News Release, February 20, 1967, https://www.nga.gov/content/dam/ngaweb/research/in-depth/provenance-liechtenstein/1967_GinevraAcquisition_NGApressrelease.pdf.

- ^ “New Girl in Town,” The Washington Post, February 23, 1967.

- ^ Harris, 73.

- ^ Anne Sue Hirshorn, “Collector’s Mania” (letter to the editor), The Washington Post, March 8, 1967.

- ^ The Washington Post, March 18, 1967.

- ^ “All the Trimmings,” The Washington Post, March 23, 1967.

- ^ “Display Ad 203,” The New York Times, March 5, 1967.

- ^ “A Winner at Last,” The Washington Post, March 20, 1967.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)