A Cartographer’s Lament: The D.C. - Virginia Boundary That Wouldn't Stay Put

There are some things all reasonable people can agree on: The Potomac River separates the District of Columbia from Virginia. An island is a piece of land surrounded by water. The finest dog breed of all is the dachshund.

Okay, maybe not the dachshund — but not the others either.

For decades, the land on the western bank of the Potomac River that is currently home to the Pentagon, Ronald Reagan National Airport, Roache’s Run Bird Sanctuary, and part of the George Washington Memorial Parkway was disputed territory. Did it belong to Virginia? The District? No one seemed quite sure.

The root of the problems can be traced back to conflicting charters and land grants in colonial times but the issues really started to mount in 1846. As students of D.C. history will remember, that was the year that the chunk of land that Virginia had ceded to the Federal government for the creation of the District of Columbia was retroceded back to Virginia.

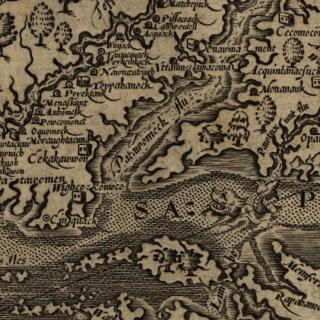

Retrocession effectively set the Virginia boundary back to where it had been in 1791, when George Washington selected the site for the new Federal city that became Washington, D.C.1 Back then, the boundary between Maryland and Virginia had been disputed on and off for decades but a widely accepted view was that the line was the “high water” mark on the Virginia side of the river.2 In other words, Maryland (and, later, D.C) owned the river and islands, while Virginia owned everything that was connected to its mainland. Seems pretty simple, right? Not in the slightest.

Given the shifting nature of river banks, particularly tidal ones like the Potomac, and the existence of half-water/half-land3 marshy areas, the “high water” line was never much of a line at all. And when you add in man-made changes brought on by dredging, filling, and development, the landscape changed significantly over time. Areas that had been underwater in 1791 were dry land by the 1920s, which created some controversy.4

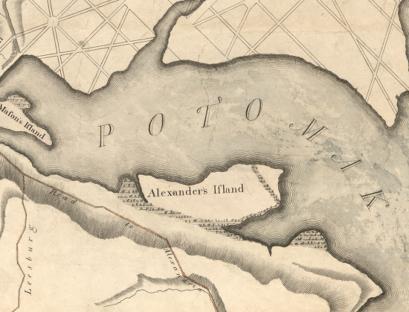

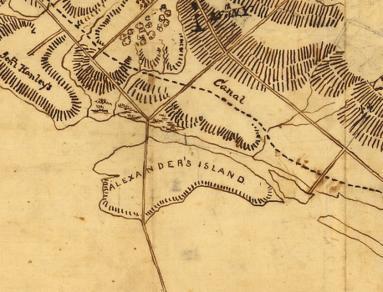

Much of the dispute centered around Alexander’s Island, which was located where the Pentagon Connector parking lot now sits. Named for the Alexander family, who had a plantation on the site in the 18th century, Alexander’s Island earned its islandhood by virtue of some quite old maps, such as Andrew Ellicott’s 1793 map of the “Territory of Columbia.” That map showed a narrow strip of marshland called Roache’s Run separating approximately 500 acres from the mainland of Virginia.5 Other maps showed Roache’s Run as a body of water.6

But over time, whatever separated Alexander’s island from Virginia’s mainland all but dried up. As the Evening Star reported in 1926, “In the course of years, the narrow channel became clogged. Gradually, the engineers believe, it underwent a process of evolution from open water into marsh and then into dry land inseparable from the Virginia shore.”7

Other factors made it even more difficult to distinguish Alexander’s Island -- and other areas where the landscape had changed since 1791 -- from Virginia. In some important ways, these areas had been treated as part of Virginia for decades. For starters, Virginia had levied taxes on them.8 It had also policed them… or at least it did sometimes. (Notably, policing and emergency response were not consistent.)9

Still, the Federal Government couldn’t quite let go of the idea that the new land on the western shore of the Potomac rightfully belonged to D.C., not Virginia. After all, the 1791 high water mark hadn’t moved. It was just no longer completely under water.

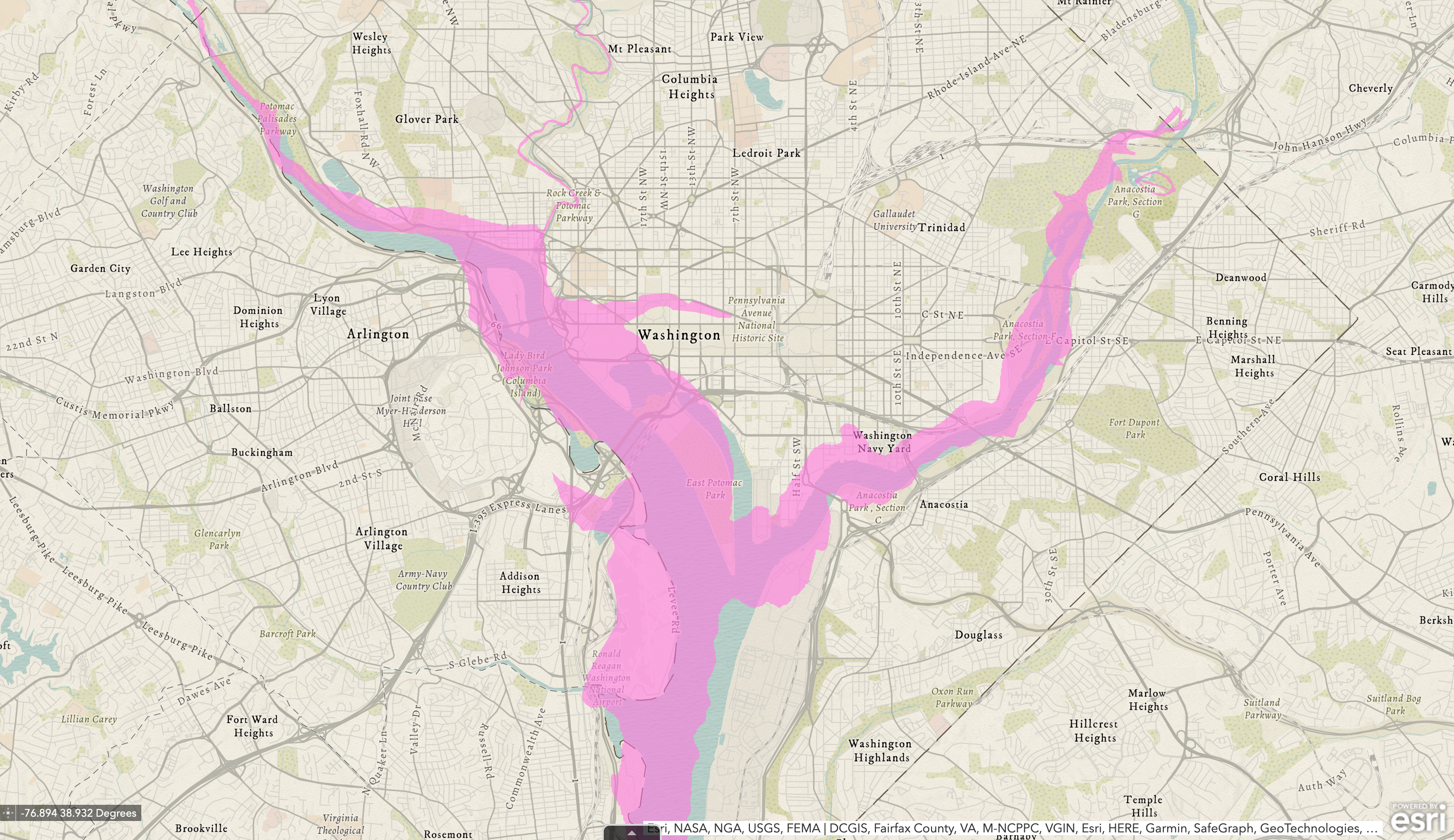

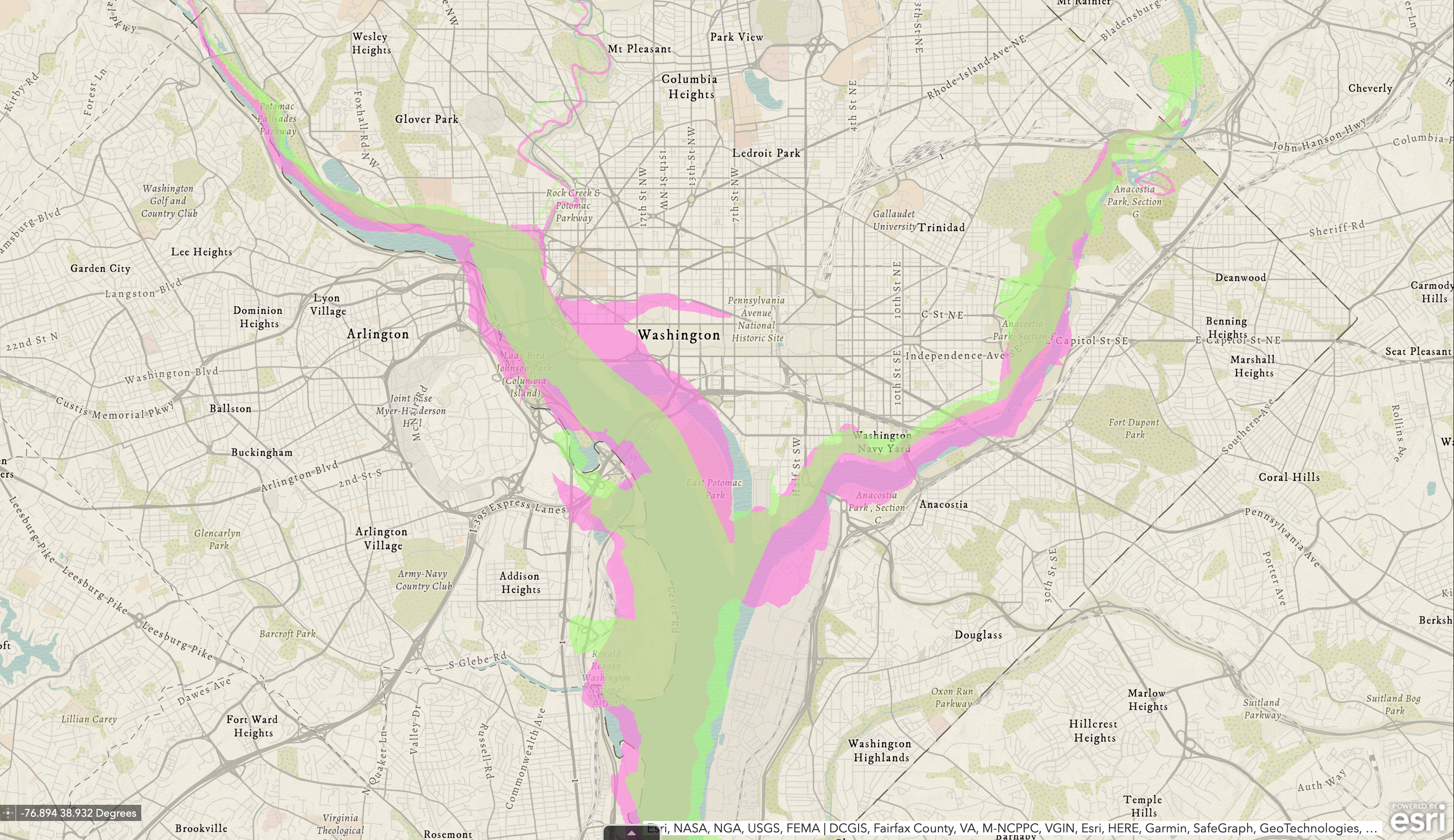

Having trouble visualizing all this? Us too. Thankfully, we are not without help. An interactive mapping tool published by the D.C. Department of Energy and Environment allows you to overlay historical maps of the District’s water bodies on top of a present day map. Playing with the chronological layers allows you to view *approximately* how the shoreline of the Potomac changed over time.

In the illustration below, the pink overlay approximates the Potomac River’s water line as mapped by Andrew Ellicott in 1793:

In this second illustration, we've added a green overlay that approximates the river bank as it was mapped by the USGS in 1917:

Notice the narrow strip of pink still visible on the Virginia side of the river. That represents area that had been underwater in the 1790s but became dry land -- and the source of controversy between Virginia and the Federal Government.

(Note: The creators of the D.C. Historic Streams tool are quick and correct to point out that the overlays and the historical maps they are based upon may not be completely accurate.10 In the centuries before GPS, mapping was tough, after all. Still, for our purposes the illustrations are valuable, because they reflect an important reality: the river and the shoreline changed considerably and created some new dry land.)

The boundary issue was a factor in several cases that went all the way to the Supreme Court, including Morris vs. United States in 1899 and Marine Railway & Coal Co. vs. United States in 1921. Both of these cases, in their own ways, came to the same conclusion: the Federal Government was entitled to the “made land” from the Potomac River – e.g. areas that had once been underwater in the Potomac but had become dry land via natural or man-made means. But these verdicts did not succeed in settling the question. Nor did a 1931 decision in Smoot Sand and Gravel Corp. vs. Washington Airport, Inc, which reaffirmed the high-water mark as the legal boundary between Virginia and D.C.

In short, Virginia was not eager to give up its claim on the land, which it had been treating as part of the Commonwealth.11 Plus, there was also the not-so-insignificant matter of disenfranchising citizens. If the Federal Government controlled the disputed land as part of D.C., then the citizens who lived there – who likely saw themselves as Virginians – would no longer have representation in Congress.

The boundary questions reached a head in the 1930s and ‘40s. With the capital region expanding rapidly, the Federal Government had a vision for land across the Potomac from D.C. – notably a new airport and a scenic parkway connecting Washington, D.C. with Mount Vernon. (You probably know that road as the George Washington Memorial Parkway.) Meanwhile, Virginia, Arlington County and private landowners had an interest in maintaining their hold of the property and their sovereignty.

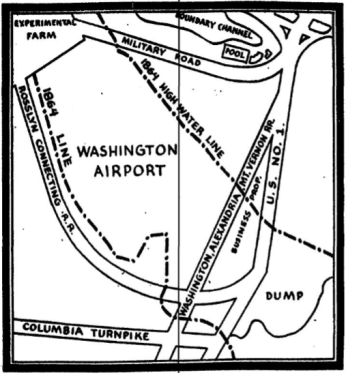

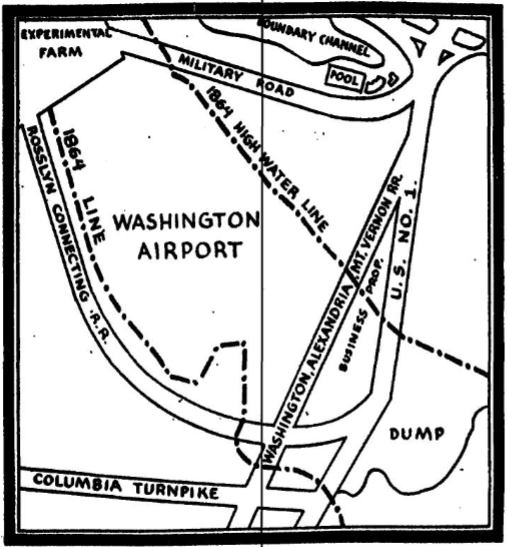

The need for an airport was particularly pressing, as Washington was being served by two small, dangerous, adjacent airports, which were located partially on the disputed land: Hoover Field and Washington Airport. It was clear that a new airport would be a great boon for the region and big business, but as the Washington Post would recall later, “the question arose as to who should police the airport, who should collect valuable gas and oil taxes, and who should regulate the sale of liquor.”12

In an effort to settle the boundary dispute once and for all, Congress created the D.C.-Virginia Boundary Commission in 1934 at the urging of Rep. Howard Smith (D-VA).13 It was comprised of (1) a representative from the Federal Government appointed by the President, (2) a representative from Virginia appointed by the Governor of Virginia and (3) a third representative that was appointed by the other two.

Over the course of 1934-1935 the Commission held several hearings where the Federal Government and Virginia argued their cases. Each offered different maps and documents which they claimed should settle the issue in their favor. While the evidence was contradictory, neither side was presenting blatant falsehoods.

Not surprisingly, lawyers for the Federal government leaned heavily on the previous Supreme Court decisions to support their case, arguing that Virginia “cannot escape recognition of the fact that the Supreme Court of the United States has ruled the entire bed of the Potomac River, opposite the City of Washington, is held by the United States in absolute sovereign dominion and control, and that the high-water line of 1791 has been declared to be the boundary of between Virginia and the District.”14 In response, attorneys representing Virginia argued that it had not been a party in those previous Supreme Court cases, which involved private entities. Thus, the high court had not had the opportunity to hear Virginia’s side of the story and the precedents should not be binding.15

In making its own claim for jurisdiction, Virginia argued that the boundary between Maryland and Virginia had been recognized as the low-water mark in a 1785 compact between the two states.16 Additionally, Virginia and Arlington County posited that they had a right to the disputed land by “virtue of prescription and long-continued occupation and possession, and the exercise of government jurisdiction over all territory above the low water mark.”17

In his closing arguments, Frank L. Ball, a former state senator who was involved in presenting Virginia’s case, attempted to frame the Federal government’s claims to the land as a dangerous overreach.

“What’s become of State’s rights, anyhow? Are they a thing of the past? Have we here in America a Mussolini government? When the Federal Government wants something, can it go and take it? States are supposed to be protected against aggression by the Federal Government.”18

In December 1935, the Commission finally issued its ruling. To the surprise of many, it sided with Virginia and recommended that the boundary be set at the then present day “low water” mark. If enacted, the recommendation would have added significant acreage to Virginia, valued at approximately $1,000,000.19

Representative Smith was delighted. He moved quickly and introduced a bill in the House of Representatives to confirm the Commission’s recommendation in January of 1936. Federal officials – particularly the National Capital Parks and Planning Commission – pushed back vigorously. NCPPC Secretary Thomas Settle predicted that if Smith got his way, the landscape would be irreparably harmed as scenic shoreline that the Federal government intended to protect as parkland would be replaced with unsightly gas stations and cheap restaurants.20

For its part, Congress was hesitant to settle the matter. Smith’s bill was referred to the House Judiciary Committee and effectively tabled. Though the bill was reintroduced several times, no further action was taken to settle to boundary question for years. According to reports, many lawmakers felt that the Supreme Court should weigh in. (Again.)21

Though Smith’s boundary bill stalled, development along the Potomac shoreline did not. By 1942, the Washington Post remarked that Arlington County was “growing so rapidly that up-to-date statistics are impossible obtain.” It was “the smallest, most thickly populated, and among the richest and greatest revenue producing county in the State of Virginia.”22 Indeed, the changes had been significant.

In 1937, workmen of the Nation Capital Parks and Planning Commission painted boundary lines, “according to Uncle Sam’s definition” on the new George Washington Memorial Parkway, U.S. Route 1, and on Military Road, “which cuts across the Washington-Hoover Airport.”23 Thanks to the markers, the Star noted (perhaps with a sense of bemusement) that, “It is now possible for a motorist traveling southward from the District to pass into Virginia along Mount Vernon Memorial Highway, get back into the District again and at the Capitol Overlook be back in Virginia again.”24

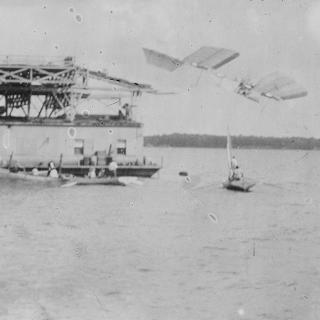

In 1938, at the urging of President Roosevelt, Gravelly Point was selected as the site for the much needed new airport. Part of the site was underwater. So, as had been the case elsewhere along the Potomac shoreline, dry land was created by dredging and dumping sand and gravel along the edge of the river.25

In the early 1940s, the construction of the Pentagon caused further metamorphosis of the river bank; the government dredged 700,000 tons of sand from the Potomac.26 The site included 146 acres from Hoover Airport, 57 acres from Arlington Experimental Farm, and 80 acres from an Army depot. Private parcels of land were usurped to build roads, and many families were evicted from their homes.27

Amidst these changes, the debate – and confusion – about jurisdiction persisted. As the Evening Star noted in 1944, if the high-water mark from 1791 was enforced as the boundary between D.C. and Virginia, then two-fifths of the Pentagon would be in D.C. and three-fifths in Virginia.28 The new National Airport, which had opened in 1941, would be similarly divided – the airport’s runways would be in the District, while the terminal would be in Virginia.29

The situation was a mess by any definition and occasionally had life-and-death consequences. Press reports detailed numerous accidents where Virginia and D.C. officials were left pointing the finger at the other to take charge.30

Finally, after years of inaction and bickering, Congress arrived at an acceptable compromise in 1945. Jennings Randolph, chairman of the House District Committee, sponsored a bill which set the boundary between D.C. and Virginia as the present day “mean high water mark.” In effect this meant that all of the land on the Virginia side of the Potomac – including land that had been created by filling in the edges of the river – would be part of Virginia.31 Meanwhile, the airport would be treated as a Federal reservation32 inside Virginia. Basically, Virginia got the land and the right to tax it, with some exceptions.33

President Truman signed the bill into law in October 1945.34 A few months later, Virginia Governor William Tuck signed a similar bill, which had been passed by the Virginia General Assembly.35 At long last, the boundary saga was over! But the next time you’re driving down the George Washington Parkway – which most reasonable people can agree is in Virginia – remind yourself that it wasn’t always so clear cut. In fact, you’ll be driving on some of the most hotly disputed land in American history.

Footnotes

- 1

On July 16, 1790 Congress passed the Residence Act, which established the permanent seat of government along the Potomac River on a site to be determined by President George Washington. The act stipulated that the land for the new federal district would be ceded to the Federal Government by Maryland and Virginia. On January 24, 1791, Washington issued a proclamation formally selecting the site that became Washington, D.C. See Residence Act: Primary Documents in American History and Proclamation.

- 2

Maryland’s claim – and later D.C.’s claim – to the Potomac River up to the high-water mark on the Virginia shore was traced back to the 1632 Charter of Maryland, which set the Maryland boundary “unto the true meridian of the first Fountain of the River of Pattowmack, thence verging toward the South, unto the further Bank of the said River.” The ‘further bank’ was interpreted the high water mark. See Cession and Retrocession of the District of Columbia.

- 3 Callender, Edward, Virginia Carter, D.C. Hahl, Kerie Hitt, and Barbara I. Schultz, eds. “A Water-Quality Study the Tidal Potomac River and Estuary — An Overview.” United States Govt Printing Office, 1984.

- 4 Evening Star. “Boundary Survey Results Due Soon: Study to Fix D.C.’s Right to Virginia Land Is Complete.” July 13, 1925.

- 5

Foster, Jack Hamilton. “Alexander’s Island.” Arlington Historical Magazine 7, no. 2 (October 1982): 23–32.

- 6

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. “Reconnaissance in Advance of Camp Mansfield.” Image. Accessed April 10, 2023.

- 7 Wheatley, William J. “District Claim to Virginia Land Depends on History.” Evening Star. October 10, 1926.

- 8 Chinn, James E. “Boundary Dispute Action Is Sought; Representative Smith to Ask Congress to Ratify Commission Findings.” Evening Star, November 19, 1936.

- 9 There were numerous reports about how crime investigations or accident responses had been bungled due to confusion over who had jurisdiction in the disputed area. However, Virginia certainly felt empowered to take action when it desired – such as 1904, when Commonwealth’s Attorney Crandal Mackey conducted raids in an effort to cleanup gambling in Jackson City, a notoriously seedy town which had been built on Alexander’s Island in the mid 1800s.

- 10 The District's Historical Streams tool is quick to point out that it is not exact. "Historical maps may include information we know to be imprecise or even inaccurate. Information may also be excluded for various reasons, providing an incomplete view of the landscape. Consistency does not indicate precision. The exact location of stream segments can differ by hundreds of feet depending on the map source."

- 11 Evening Star. “Boundary Survey Results Due Soon: Study to Fix D.C.’s Right to Virginia Land Is Complete.” July 13, 1925.

- 12 Haley, Pope. “War Revives D.C.-Virginia Boundary Dispute.” Washington Post, April 19, 1942, pg. 11.

- 13 Evening Star. “Bill for Boundary Commission Gets O.K. of Committee.” January 25, 1934.

- 14 Evening Star. “Federal Parkway Held Menaced By Virginia’s Claim.” December 17, 1934.

- 15 Collier, Rex. “Exchange of Land May End Dispute Over Boundary: U.S. and Airport Owners Would Negotiate Trade Under Proposed Plan.” Evening Star, September 15, 1935.

- 16

LII / Legal Information Institute. “VIRGINIA v. MARYLAND.”

- 17 Evening Star. “Virginia Presents Boundary Claims; State Joins Arlington in Case Argued Before Commission.” November 26, 1934.

- 18 Evening Star. “‘Mussolini Rule’ in U.S. Denounced; Boundary Plea Questions Invasion of Rights of Virginia.” September 13, 1935.

- 19 Evening Star. “Boundary Report Favors Virginia; Commission Says Low Water Mark of River Is ‘Fair’ Line.” December 7, 1935.

- 20 Evening Star. “Bill Would O.K. Boundary Ruling.” January 7, 1936.

- 21 Evening Star. “Boundary Report Verdict Expected; Fate of Commission Findings Up to House Committee This Week.” February 9, 1936.

- 22 Haley, Pope. “War Revives D.C.-Virginia Boundary Dispute.” Washington Post, April 19, 1942, Pg. 11.

- 23 Evening Star. “D.C.-Virginia Boundary Lines Marked on Mt. Vernon Highway.” October 20, 1937.

- 24 Evening Star. “D.C.-Virginia Boundary Lines Marked on Mt. Vernon Highway.” October 20, 1937.

- 25

flyreagan.com. “History of Reagan National Airport.” Accessed April 6, 2023.

- 26

History.com. “Pentagon - Location, Building Timeline, 9/11,” June 10, 2019.

- 27

Vogel, Stephen. “The Battle of Arlington: How the Pentagon Got Built.” Washington Post.

- 28 Evening Star. “Present D.C. Boundary Is Through Pentagon, Map Expert Asserts.” March 8, 1944.

- 29 Evening Star. “Airport Jurisdiction.” July 19, 1941.

- 30 This was a common theme throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. See Evening Star. “Park Police Continue to Patrol Disputed Area in Virginia; Territory Beyond Highway Bridge Has Been Center of Long Controversy.” October 6, 1939; Evening Star. “Park Police Continue to Patrol Disputed Area in Virginia; Territory Beyond Highway Bridge Has Been Center of Long Controversy.” October 6, 1939.

- 31 Washington Post. “House to Vote On D.C.-Va. Boundary Bill.” November 30, 1943.

- 32 Washington Post. “Virginia-D.C. Boundary Line Bill Passed.” October 23, 1945.

- 33 Washington Post. “Truman Signs Bill to Settle District-Virginia Boundary.” November 1, 1945.

- 34 Washington Post. “Truman Signs Bill to Settle District-Virginia Boundary.” November 1, 1945.

- 35 Evening Star. “Gov. Tuck Signs Bill Establishing Virginia-District Boundary Line.” February 19, 1946.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)