“Ground [the statues] into dust!” – The Downfall of Two District Memorials

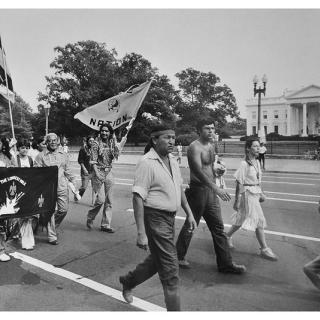

With the recent protests in response to the murder of George Floyd and the continued unearthing of our nation’s racist history, conversation regarding what history we set in stone is back at the forefront. In the District, memorial removals are extremely rare occurrences, but that doesn’t mean they have never happened before. In the late 1950s, two of the Capitol building’s most significant monuments were removed, despite the fact that a future president himself advocated for their installment: Horatio Greenough’s The Rescue and Luigi Persico’s Discovery of America. Largely due to public pressure, the statues were taken down during the building’s remodeling in 1958 and never re-erected.[1]

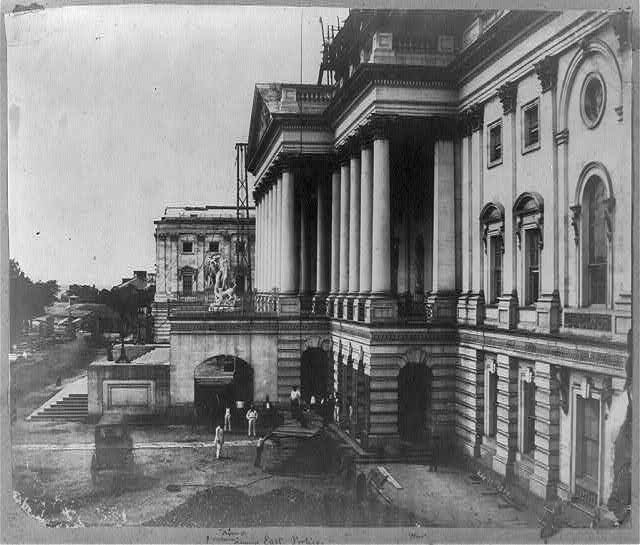

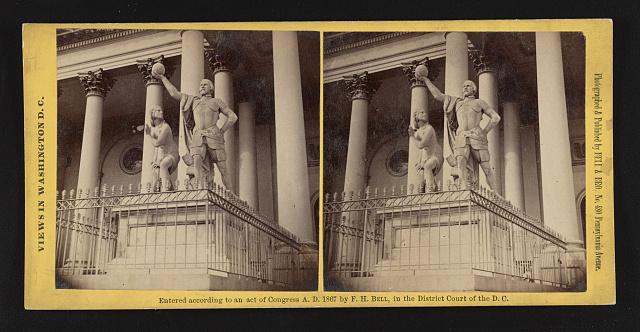

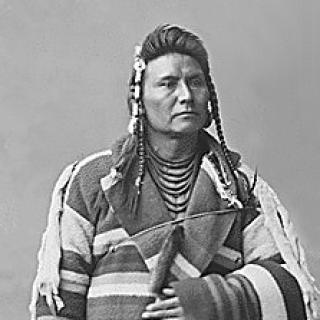

For over a hundred years, the sculptures loomed over the Capitol’s exterior east wing. The Rescue depicted an intimidating white frontiersman overpowering an American Indian man, with a cowering Indigenous woman in the background. Mirroring The Rescue stood Discovery of America –a similar marble sculpture, this time of Christopher Columbus poised beside an awe-struck American Indian woman. Though it’s unlikely such an idea would be approved today, at the time of the sculptures’ proposal in 1836, white Americans believed U.S. expansion and colonizers’ triumph over Indigenous peoples were events to be celebrated. President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act just six years prior, and it seemed fitting that the sculptures “convey the idea of the triumph of the whites over the savage tribe,” as artist Greenough would later remark.[2]

Senator James Buchanan (whose memorial would one day also spark controversy), initially approached Congress to advocate for a single memorial sculpted by renowned Italian artist Luigi Persico. Many congressmen resisted; after all, they contested, such an American memorial should be sculpted by an American (Columbus was, of course, Italian and sponsored by the Spanish, but that didn’t seem to be a point of argument). To mediate, Senator William Preston recommended a second sculpture be commissioned by Horatio Greenough, an American artist “of unquestioned genius; one calculated to do honor to his country, and whom his country should delight to honor.”[2] After reaching this compromise, the Senate passed a resolution on May 17, 1836. The resolution commissioned two sculptures to be “placed upon the pedestals upon each side of the steps which form the front entrance to the Capitol.”[2] It wasn’t until April 3, 1837, though, that President Van Buren finally signed off on the official authorization.

There’s no doubt as to the intention of the sculptors. Both Greenough and Persico did their best to meet Congress’s vision of white colonizers' victory over Indigenous peoples, and the sculptures’ depiction of American Indians reflects this. As mentioned earlier, Greenough focused on white “triumph” over Native “savage[ry].” Buchanan later remarked that Persico’s Discovery represented “the great discoverer when he first bounded with ecstasy upon the shore, all his toils past, presenting a hemisphere to the astonished world, with the name America inscribed upon it. Whilst he is thus standing upon the shore, a female savage, with awe and wonder depicted in her countenance is gazing upon him.”[2] The sculptures were completed and installed in the Capitol in 1853.[2]

Although American Indians had long taken issue with the statues’ depiction of their people, it wasn’t until 1934, nearly a hundred years after the memorials’ commission, that widespread opposition really amped up. The year marked a turning point in white Americans’ attitudes towards American Indians, as the Native American Reorganization Act encouraged tribal government and acknowledged that white colonizers “took away [Native Americans’] best lands; broke treaties, promises; tossed them the most nearly worthless scraps of a continent that had once been wholly theirs.”[3] In 1939, the House submitted (but didn’t pass) a joint resolution that recommended The Rescue be “ground into dust and scattered to the four winds, that no more remembrance may be perpetuated of our barbaric past, and that it may not be a constant reminder to our American Indian citizens.”[4]

The 1950s saw yet another wave of resistance, especially as Congress began to consider bills acknowledging Native American sovereignty. The National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) took advantage of this momentum and lobbied for the statues’ removal.[5] A woman named Leta Myers Smart also helped in the fight, publishing a slew of open letters condemning the sculptures.

“The American Indian is no longer, if he ever was, the blood thirsty savage Greenough made him out to be in this group of sculpture,” Smart wrote to Harper’s Magazine. “We feel we have to rescue the Indians from these deplorable straits. Not forgetting the other reasons why this should be done or because those statues are bad propaganda for America and would make excellent fodder for our enemies.”[6] In another letter, Smart remarked that “the pieces would be in better keeping for the right kind of propaganda for Americanism.”[6]

As one journalist remarked, “getting approval to remove [a memorial] has about as much of a chance of winning over Congress as an effort to replace the statue of Freedom atop the Capitol with one of Whistler’s mother;”[7] but plans to remodel the Capitol building in 1958 provided a loop hole. Renovations placed the decision of the statues’ fate in the hands of the ‘Five Man Commission for the Extension of the U.S. Capitol,’ and the commission eventually decided it was time to put the statues to rest.[8]

The New York Times commented on the significance of this event, pointing out that “extremely few – too few – [statues] ever seem to disappear from the Washington landscape.” This could be because, as we’ve seen recently, the prospect of taking down historical markers ignites controversy. After all, if they depict historical events or figures, what’s the point of taking them down?

Well, in the case of Discovery and The Rescue, art historian Vivien Green Fryd’s work – which served as a great resource for this article - sheds some light. Green Fryd’s research notes how lawmakers cited the statues in arguments for policies that proved harmful for Indigenous peoples. Congressmen Belser, for example, advocated for the acquisition of Texas in 1845, stating: “In the arrangements of Providence, Indian possession has gradually given way before the advances of civilization…Let gentlemen look upon those two figures that have recently been erected on the eastern portico of the Capitol, and learn an instructive lesson…the artist, when he made Columbus superior over the Indian princess in every respect, knew what he was doing.”[9] As Green Fryd’s commentary on the statues illustrates, memorials often serve as notable reflections of current rhetoric.

The congressman who once contended that The Rescue “be ground into dust” might be happy to know that they successfully predicted the memorial’s demise. Call it divine providence or a mere mishap, but in 1976, movers dropped “the heroic statue,” and the head of the frontiersman (literally) went rolling.[10] Guess he was less of a victor than Greenough intended. The statue was in the process of being moved into the Smithsonian’s storage center, and today, the fragments remain stowed next to Persico’s Discovery.

It’s easy to forget about these statues since we no longer see them, but their history could help us contextualize more current debates about memorials. Even though memorial removal may seem like a revolutionary, or even impossible, task, The Rescue and Discovery of America remind us that it’s a phenomenon the city’s already witnessed.

Footnotes

- ^ Crated Capitol Statues Unmourned: Disgraceful" Reminder Both Statues RemovedBy John F. Lindsay Staff Reporter The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973); Jan 5, 1961;

- a, b, c, d, e Fryd, Vivien Green. "Two Sculptures for the Capitol: Horatio Greenough's "Rescue" and Luigi Persico's "Discovery of America"." American Art Journal 19, no. 2 (1987): 16-39. Accessed June 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/1594479.

- ^ Wilcomb E. Washburn, ed, The Indian and the White Man, p. 393

- ^ Fryd, Vivien Green. "Two Sculptures for the Capitol: Horatio Greenough's "Rescue" and Luigi Persico's "Discovery of America"." American Art Journal 19, no. 2 (1987): 16-39. Accessed June 11, 2020. doi:10.2307/1594479.

- ^ "They Are Ancestral Homelands": Race, Place, and Politics in Cold War Native America, 1945-1961, Rosier, Paul C The Journal of American History; Mar 2006; 92, 4; eLibrary pg. 1300

- a, b Joseph Genetin-Pilawa, The Indians' Capital City: Native Histories of Washington DC. 2015. Video. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/webcast-6706/>.

- ^ Alvin Shuster, “Lest Washington Be 'An Unplanned Cemetery': The plethora of monuments,” New York Times (1923-Current file); Sep 11, 1960; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times

- ^ “Stony Silence in Statuary Issue,” Evening Star (published as THE EVENING STAR.) - October 12, 1956 - page 40

- ^ Fryd, Vivien Green. "Two Sculptures for the Capitol: Horatio Greenough's "Rescue" and Luigi Persico's "Discovery of America"." American Art Journal 19, no. 2 (1987): 16-39. Accessed June 12, 2020. doi:10.2307/1594479.

- ^ “Shattering Day for Statue,” Evening Star (published as The Washington Star), May 11, 1976, page 24

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)