Anti-Lynching Activism at Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church

On December 4th, 1931, a Black man named Mark Williams was murdered by a mob in Salisbury, Maryland.[1] Accused of killing his white employer, Williams was taken from his hospital bed, hanged from a tree until he died, dragged into Salisbury’s Black neighborhood, doused in gasoline and set on fire.[2] Lynchings like these were not uncommon in many states and had become a national problem after the end of Reconstruction.[3]

These kinds of “spectacle” lynchings almost always included a ritual similar to Williams’ murder, with the torture and public execution (by hanging, stabbing, shooting, and/or burning alive) of primarily Black men but also Black women and children. It often culminated with spectators taking pieces of the victim’s body as souvenirs and with pictures taken.[4] Spectators could number from a handful to thousands.

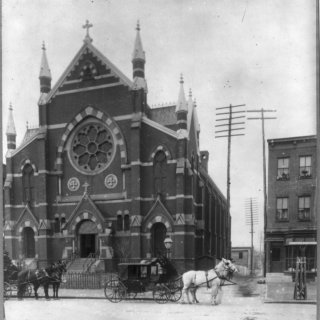

The pervasiveness of this racial terrorism ultimately led many Black activists to devote their energies to anti-lynching efforts. This included famed journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett and writer/abolitionist Frederick Douglass, both of whom gave anti-lynching speeches at Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church located at 1518 M Street NW.

Black communities found themselves in desperate need of action against this extreme form of anti-Black violence.[5] Northern Black churches like Metropolitan AME generally had more political clout and resources to host activists and were also less prone to extreme violent retaliation than their Southern counterparts, which led to much of the activism tours by Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Frederick Douglass being conducted in Northern cities.[6]

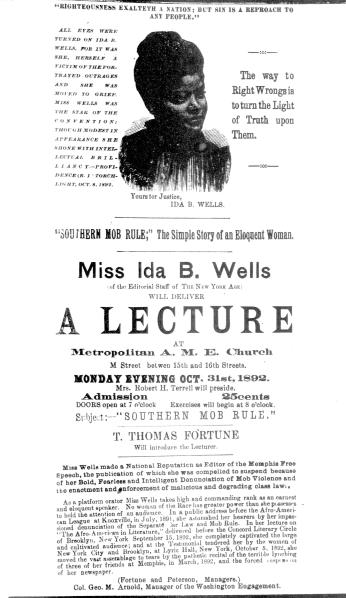

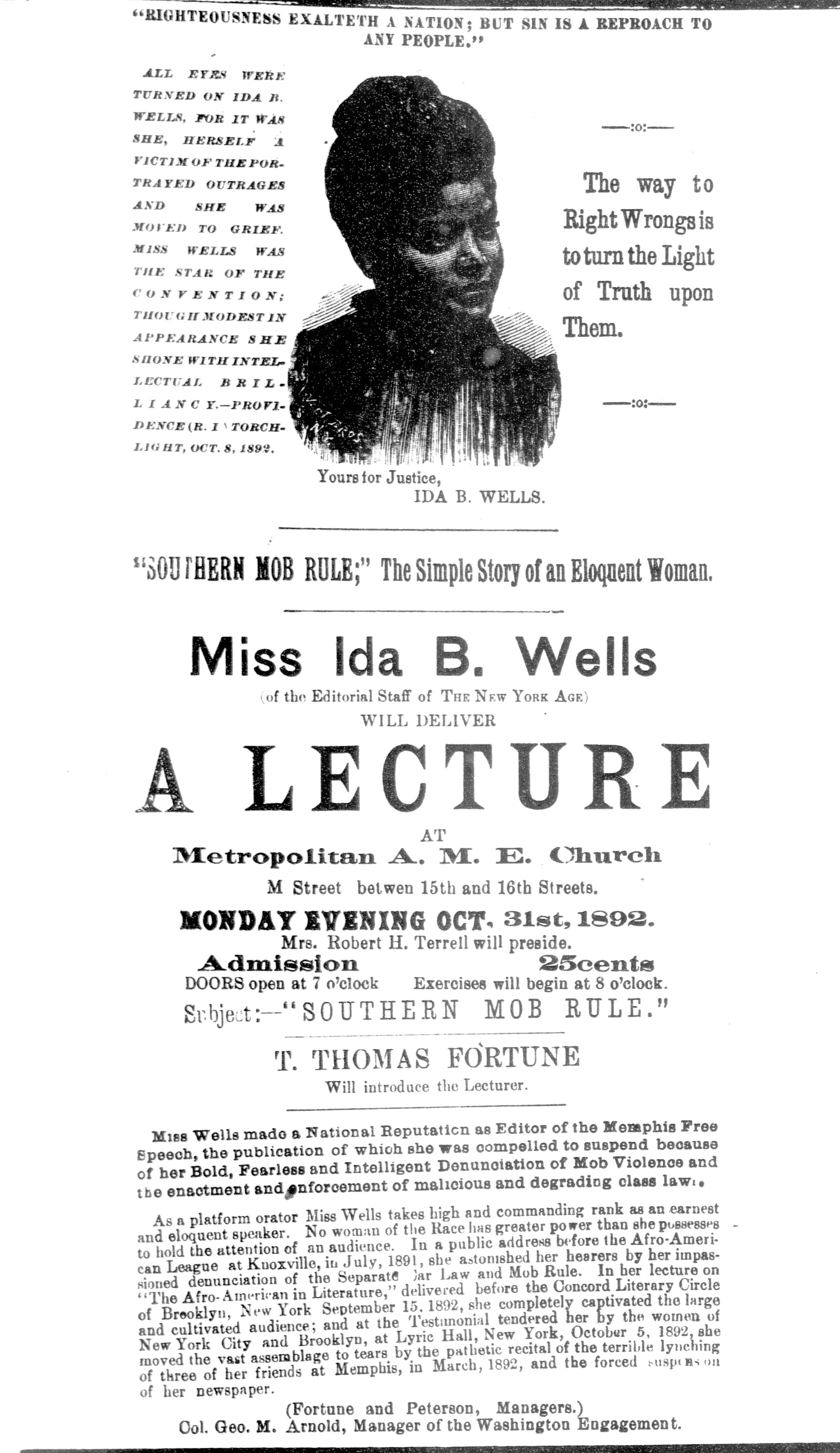

An investigative journalist, teacher, and activist/lecturer – Ida B. Wells-Barnett was somewhat of a vanguard in how she addressed lynchings. After three Black men were lynched in Memphis in March of 1892, Wells-Barnett wrote a scathing editorial in The Memphis Free Speech (of which she was co-owner and editor) that refuted one of the common reason for lynching – accusations of rape by Black men.[7] Wells-Barnett asserted that most white claims of sexual assault by Black men were not only false, but were actually pretenses to cover-up miscegenation.[8] [9] The editorial resulted in The Memphis Free Speech being destroyed and Wells-Barnett having to leave Memphis because of death threats.

In October of that same year, Wells-Barnett gave one of her anti-lynching speeches (known as “lectures”) at Metropolitan AME. Attendance as low even though the lecture was publicized in the weekly Black newspaper The Washington Bee. Wells-Barnett returned to Metropolitan AME in January of 1893 at the request of Frederick Douglass to a much larger audience.[10]

On January 9th, 1894, Frederick Douglass delivered one of his last speeches before his death – entitled “The Lessons of the Hour” at Metropolitan AME. The speech was an epic condemnation of lynching – from its pervasiveness, to its general acceptance amongst both Southern and Northern whites. Douglass criticized the “Negro problem” rhetoric as a form of displaced and projected blame – one that “shields the guilty, and blames the innocent. Makes the negro responsible and not the nation."[11]

Douglass also denounced the extreme lack of due process for Black victims that simultaneously allowed for the extralegal killings and offered no retribution:

“In its thirst for blood and its rage for vengeance, the mob has blindly, boldly and defiantly supplanted sheriffs, constables and police. It has assumed all the functions. It laughs at legal processes, courts and juries, and its red-handed murderers range abroad unchecked and unchallenged by law or by public opinion.”[12]

For the speech’s 100th anniversary actor Fred Morsell performed his one-man play in which he re-enacted the speech. Filmed for PBS’s Bill Moyers Journal, the episode “Presenting Mr. Frederick Douglass” was filmed at Metropolitan AME.

Though the 1890s are considered the numerical height of lynchings, they continued well into the mid-20th century as evidenced by lynchings of Black veterans after both World Wars, and the gruesome murder of 14-year old Emmett Till – largely considered to be the catalyst of the Civil Rights Movement.[13] And only 40 years ago Michael Donald was murdered by two Ku Klux Klan members in 1981. Still, no federal anti-lynching law was ever passed.

Activism against state sanctioned anti-Black violence is ongoing and will continue the tradition of greats like Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Frederick Douglass, particularly with modern day activists and even the United Nations drawing parallels between spectacle lynchings of the past and modern police violence.[14] [15]

Footnotes

- ^ “An American Tragedy,” The Maryland Historical Society Library, 29 Nov 2012. Accessed 9 December 2016.

- ^ Jeremy Cox, “Vigil Planned to Mark Salisbury Lynching Anniversary,” 30 Nov 2016, DelmarvaNow.com. Accessed 9 December 2016.

- ^ Campbell Robertson, “History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names,” The New York Times, 10 Feb 2015. Accessed 29 Nov 2016.

- ^ Grace Elizabeth Hale, “Deadly Amusements: Spectacle Lynchings and the Contradictions of Segregation as Culture,” in Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1995), 203-204.

- ^ Eric McDaniel, “When Will the Call Be Made? A History of Black Church Political Activism” in Politics in the Pews: The Political Mobilization of Black Churches (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2009), 71.

- ^ Ibid., 63.

- ^ Patricia Hill Collins, “Introduction,” in On Lynchings by Ida B. Wells-Barnett (Amherst, New York: Humanity Books, 2002), 14, 21.

- ^ Wells-Barnett also asserted that the real reason for the men’s death was that the grocery store they owned and operated had become a business rival to the white owned store nearby. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, “Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” edited by Shirley Wilson Logan (College Park: The University of Maryland, Voices of Democracy – The U.S. Oratory Project, 2007), para. 5-14. Accessed 29 Nov 2016.

- ^ Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases ebook (New York: The New York Age Print, 1892), 5-8. Accessed 29 Nov 2016.

- ^ Patricia A. Schechter, “The Body in Question,” in Ida B. Wells and American Reform: 1880-1930 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 90.

- ^ Frederick Douglass, “Address… January 9th on the Lessons of the Hour,” manuscript/mixed material (Baltimore: Press of Thomas and Evans, 1894” 30 Address ... January 9th, 1894, on the Lessons of the Hour. Baltimore: Press of Thomas and Evans, 1894. Accessed 29 Nov 2016.

- ^ Ibid., 4-5.

- ^ “Lynching in America: Targeting Black Veterans,” Equal Justice Initiative. Accessed 13 Dec 2016.

- ^ Chauncey Devega, “A Modern Day Lynching: Why I Will Not Watch the Video of Alton Sterling Being Killed By Baton Rouge Police,” Salon.com. 7 Jul 2016. Accessed 12 Nov 2016.

- ^ “UN Experts Urge US to Address Legacies of the Past, Police Impunity and ‘Crisis of Racial Injustice’,” UN News Center. Accessed 12 Nov 2016.

Additional Resources

“An American Tragedy.” The Maryland Historical Society. November 29, 2012. Accessed December 9, 2016. http://www.mdhs.org/underbelly/2012/11/29/an-american-tragedy/

Ball, Nathaniel C. “Memphis and the Lynching at the Curve.” The Benjamin L. Hooks Institute for Social Change Blog. The University of Memphis. September 30, 2015. https://blogs.memphis.edu/benhooksinstitute/2015/09/30/memphis-and-the-…

Barnett-Wells, Ida Bell. “Lynch Law In All Its Phases.” Edited by Shirley Wilson Logan. College Park: The University of Maryland, Voices of Democracy – The U.S. Oratory Project, 2007. Transcript. http://voicesofdemocracy.umd.edu/wells-lynch-law-speech-text/

Barnett-Wells, Ida Bell. “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” New York: The New York Age Print, 1892. Pamphlet ebook. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htm

Brown, DeNeen L. “History of lynching on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.” The Washington Post. July 20, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/local/wp/2015/07/20/history-of-lync…

Collins, Patricia Hill. Introduction to On Lynchings, by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 9-23. Amherst, New York: Humanity Books, 2002.

Cox, Jeremy. “Vigil Planned to Mark Salisbury Lynching Anniversay.” DelmarvaNow. November30th, 2016. Accessed December 9th, 2016. http://www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/2016/11/30/vigil-planned-mark-sal…

Devega Chauncey. “A Modern Day Lynching: Why I Will Not Watch the Video of Alton Sterling Being Killed by Baton Rouge Police.” Salon.com. July 7, 2016. Accessed December 12, 2016.

Douglass, Frederick. Address ... January 9th, 1894, on the Lessons of the Hour. Baltimore: Press of Thomas and Evans, 1894. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mfd.26001/.

Equal Justice Initiative. Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror. Second Edition. http://eji.org/sites/default/files/lynching-in-america-second-edition- summary.pdf

Equal Justice Initiative. Lynching in America: Targeting Black Soldiers. Accessed December 13, 2016. http://eji.org/sites/default/files/lynching-in-america-targeting-black-…

Hale, Grace Elizabeth. “Deadly Amusements: Spectacle Lynchings and the Contradictions of Segregation as Culture.” In Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940, 199-239. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995.

Harris, Fredrick C. “Black Churches and Civic Traditions: outreach, Activism, and the Politics of Public Funding of Faith-Based Ministries.” In Can Charitable Choice Work?: Covering Religion’s Impact on Urban Affairs and Social Services, 140-156. Edited by Andrew Walsh. Hartford: Pew Program on Religion and the News Media and the Lenoard E. Greenberg Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life, 2001.

“Lynchings: A Shameful Chapter in Virginia History.” WTKR.com. May 13, 2016. Accessed December 9, 2016. http://wtkr.com/2016/05/13/lynchings-a-shameful-chapter-in-virginia-his…

McDaniel, Eric. “When Will the Call Be Made? A History of Black Church Political Activism.” In Politics in the Pews: The Political Mobilization of Black Churches, 57-77. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, 2009.

Robertson, Campbell. “History of Lynchings in the South Documents Nearly 4,000 Names.” The New York Times. February 10, 2015. Accessed November 26th, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/10/us/history-of-lynchings-in-the-south-…

Schechter, Patricia A. “The Body In Question.” In Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American Reform, 1880-1930, 81-120. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Accessed November 29, 2016. ProQuest Ebook Central.

“UN Experts Urge US to Address Legacies of the Past, Police Impunity and ‘Crisis of Racial Injustice.’” UN News Center. Accessed December 12, 2016. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=53124#.WFOAYFMrLIV

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)