Statuary and Dignitaries: A Meridian Hill Ceremony Helps Heal a Diplomatic Crisis

If you take a stroll through Meridian Hill Park in Columbia Heights, you will find two noteworthy statues: on the lower level, a standing figure of the Italian poet, Dante Alighieri; on the upper terrace, an equestrian statue of the French saint, Jeanne d’Arc, or, Joan of Arc, anglicized. Interestingly enough, these two artworks were unveiled at the park within one month of each other—Dante on Dec. 2, 1921, and Jeanne following on Jan. 6, 1922. Walking past these serene bronze monuments, few would guess their pivotal role a century-old saga when rumored remarks in Washington led to riots in Europe.

In late 1921, the U.S. capital hosted a historic conference: for the first time, the most powerful countries would discuss naval disarmament.[1] After the horrors of the first World War, the major powers aspired toward lasting peace. Of course, the major powers also aspired toward lasting power, which ensued in an arms race. This is where the Washington Naval Conference came into play.

As a result, from November of 1921 to February of 1922, political dignitaries from Britain, France, Italy, Belgium, Japan, China, Portugal and the Netherlands came to the District to discuss international arms control.[2]

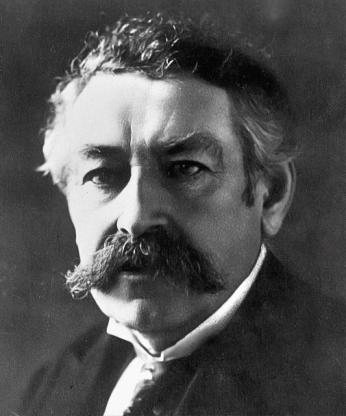

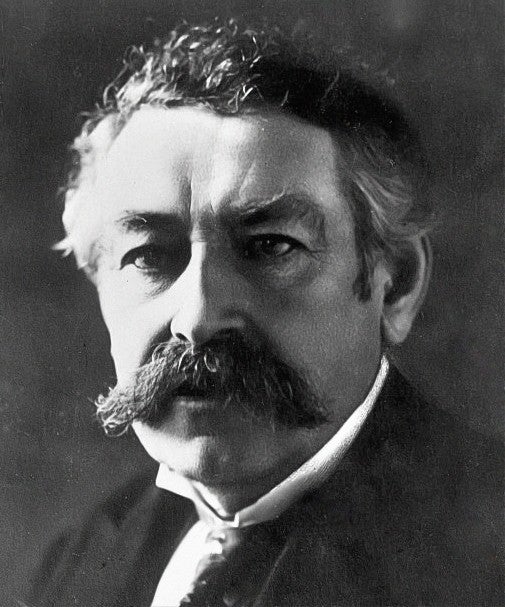

On Nov. 26, 1921 a press report had grave consequences thousands of miles away. That day, rumors started circulating that Premier Aristide Briand of France had spoken some unsavory words to the Italian delegate Senator Carlo Schanzer regarding Italy’s government and military.

“There have been reports of a spirited and rather exhausted interchange,” relayed one New York Times article, “in the course of which both those statesmen were said to have been drawing very heavily on the support of pungent words and phases [sic] in the French language which Senator Schanzer speaks with great fluency.”[3]

A Washington Post article expressed concern that the incident implicated “grave danger of a lasting enmity springing up between the two leading Latin nations of Europe, to the evident jeopardizing of world peace”[4]

While no article went as far as to say what M. Briand allegedly said, newspapers described his words as “slurs,”[5] “unkind words,”[6] “slander,”[7] “a clash of words”[8] and “remarks of an offensive and disparaging character.”[9]

News of this purported incident catalyzed anti-French demonstrations in Turin and Naples where, according to the Evening Star, “several persons were wounded in a revolver duel between the police and the demonstrators”[10] and “there were casualties.”[11] A mob of students and Fascisti demonstrated outside of the French consulate and burned a French flag.[12] The riot was extinguished by 300 troops, commissioned to restore order.[13]

The crazy part: the incident that inspired such a spirited public outcry didn’t actually happen. The next day, delegates in Washington worked emphatically to control the damage and clear up the misinformation.

Senator Schanzer sent a cable message to the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pietro Tomasi Della Torretta. He wrote: “No such incident occurred. The discussion in the committee meeting was lively but always correct. M. Briand expressed the French point of view, while I vigorously maintained the Italian standpoint. M. Briand used no language which could in any way be interpreted as offensive to Italy.”[14]

When the arms conference reconvened on Nov. 29, Secretary of State Charles Hughes directly addressed the controversy. In a lengthy speech, he vehemently denied the claims of the false report.

He said:

Not only was the debate always courteous, but at no moment did it go beyond the bounds of becoming intensity, which, as a matter of fact, is perfectly legitimate even between allies when they have before them questions of the highest importance. It is perfectly certain a priori that Mr. Briand would never have said such things as have been put into his mouth. How could he have done so, when the closest bonds of friendship and alliance exist between the two countries? The two nations have always been friends. France cannot forget the great extent of her cultural and spiritual debt to Italy. The blood of the two peoples has flowed on the same battlefields for the same cause.[15]

Coincidentally, this incident happened at the same time that two statues were being commissioned as gifts from Italy and France to America. A French national heroine and an Italian literary giant would have to dwell in the same park.

These two statues were intended to symbolize loyalty and friendship with the United States. The Italian donor, Chevalier Carlo Barsotti, expressed the “desire to show in tangible form our love, devotion and loyalty to this great nation.”[16] The Jeanne d’Arc monument was a gift from the Society of French Women of New York to women of the United States. In a telegram read at the unveiling ceremony, the French president said: “Her sublime virtue will be better understood by the women of the United States in that, as they have shown us, they know how to practice to the highest degree courage and devotion.”[17]

Nonetheless, the opportune timing of these gifts tempted statesmen and the press to claim that these two statues coexisting in the same park symbolized a new unity between Italy and France. Because they were unveiled during the Washington Naval Conference, numerous international dignitaries attended each ceremony.[18] The stage was set for diplomacy.

The Washington Post described the Dante dedication ceremony as a “love feast” between the French and Italians.[19] In a speech, the French politician René Viviani said:

My words, flying through space, will tomorrow be in Italy. As they leave my heart they will find their way into the hearts of the Italians. We belong to the same families and, so far as I am concerned, I shall never forget the sacred memories and the heroic emotions which a war waged together imprinted on my soul as in a sanctuary, and which I wish you to see.[20]

Similarly, one month later when the monument of Jeanne d’Arc was unveiled, the Post remarked:

From its nearby position the recently unveiled statue of Dante, the immortal poet of the Italians, will be conspicuous. The statue was given at a time when harsh words had passed between Italy and France and the presentation was made in a semi-official pledge of national peace and fellowship between the two nations. The Jeanne d’Arc statue, standing so close to it, will be an emblematic interpretation of the good feeling which France has for Italy.[21]

We may never know whether insulting words passed between Premier Briand and Senator Schanzer, but the aftermath of this strange saga certainly points to rising tensions between Italy and France after World War I. When the ice is already thin, incautious journalism can be the heavy boot that breaks it.

Footnotes

- ^ “The Washington Naval Conference, 1921-1922.” Office of the Historian, Department of State, United States of America. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/naval-conference.

- ^ “Washington Naval Conference.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washington_Naval_Conference.

- ^ "Italy for Warning on Europe’s Armies.” New York Times (1857-1922), Nov 26, 1921. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/italy-warning-on-europes-armies/docview/98305451/se-2? accountid=46320.

- ^ "Eloquence to the Rescue." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 03, 1921. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/eloquence-rescue/docview/145826925/se-2?accountid=46320.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Italy and France Unite Under Dante.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Dec 02, 1921. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/italy-france-unite-under-dante/docview/145839966/se-2? accountid=46320.

- ^ "The Basis of Peace." The Washington Post (1877-1922), Nov 30, 1921. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/basis-peace/docview/145851191/se-2?accountid=46320.

- ^ “Anti-French Riots Spread Over Italy.” Evening Star. November 27, 1921.

- ^ “Hughes Denies Slur by Briand on Italy.” New York Times (1857-1922), Nov 29, 1921. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/hughes-denies-slur-briand-on-italy/docview/98529038/se-2? accountid=46320.

- ^ “Anti-French Riots Spread Over Italy.” Evening Star. November 27, 1921.

- ^ “Hughes Denies Slur.” New York Times.

- ^ “Anti-French Riots in Italian Cities.” New York Times (1857-1922), Nov 27, 1921. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/anti-french-riots-italian-cities/docview/98263173/se-2? accountid=46320.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Anti-French Riots Spread Over Italy.” Evening Star. November 27, 1921.

- ^ “Hughes Denies Slur.” New York Times.

- ^ “Italy and France Unite Under Dante.” The Washington Post.

- ^ "Jusserand Lauds Maid of Orleans,” Evening Star, January 7, 1922: 4. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/apps/news/document-…? p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A13D5DA85AE05A305%40EANX- NB-1441A828A0936AA0%402423062-144005C303D7F688%403-144005C303D7F688%40.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Italy and France Unite Under Dante.” The Washington Post.

- ^ “Jeanne d’Arc’s Statue is Ready.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Jan 3, 1922. https://search-proquest- com.dclibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/jeanne-darcs-statue-is-ready/docview/146108104/se-2? accountid=46320.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)