The Failed Attempt to Build Disney's America in Virginia

On a sunny afternoon in 1991 two men in dark suits emerged from the serene fields of Haymarket, Virginia and made their way into town. Their presence raised eyebrows among locals who were used to only spotting wildlife and a few family farms as they passed through the rolling hills of Prince William County. Introducing themselves to residents under fake names, the curious pair asked anyone and everyone for the inside scoop on the surrounding land. It was clear to the town that the men were not in the Piedmont for pleasure. A calculating glint appeared in their eyes every time they looked at any sprawling meadow or field of tall grass underneath the bright blue sky. Their survey of Virginia’s natural landscape was purely business.

For Haymarket families, it was still a mystery as to why these men were giving their small-town any attention. Typically the only tourists that stopped by were busloads of school children or history buffs interested in visiting the County’s historic battlefields like the Manassas National Battlefield Park where the two Battles of Bull Run were fought during the Civil War. These well-dressed men seemed to have an uncanny interest in the land, but kept their identities and intentions under wraps. For now, locals could only wonder, who were these mysterious men working for and why were they here?

The answer came two years later at a press conference in November, 1993. Reporters gathered around Disney Chairman, Michael D. Eisner, as he proudly announced the company’s up to then secret plan to acquire land in Haymarket for a new theme park called “Disney’s America”. Dedicated to celebrating American history, Disney announced plans to develop not only its third amusement park, but also hotels, residential homes, stores, and golf courses in the surrounding area.[1]

Eisner traced the park’s inspiration to a recent trip to Colonial Williamsburg, and told reporters, “I promise you 90% of the kids in America don't know who lived in Mount Vernon, Montpelier or Monticello” as he talked about his hopes to provide a new place for history to live outside of the stony depictions found in textbooks and museums.[2] Enthusiastic that Disney’s America would provide an alternate historical and entertainment space for tourists visiting the Washington, D.C. area, Disney officials made it clear that the park would impress visitors from all over the world with exhibits, re-enactments, and rides brought to life with virtual reality.

At the conference, Haymarket residents were surprised to discover that the men they spotted wandering around the County’s rolling hills were actually undercover Disney representatives, who had disguised their identities so that the company could buy 3,000 acres of land at very low prices.[3] For Disney, Haymarket’s historical heritage and close proximity to Washington were of paramount importance. Early brochures classified the proposed park “as a compliment to [visitors’] experience of our nation's capital in Washington D.C.”, designed to be a fun, one-day experience.[4]

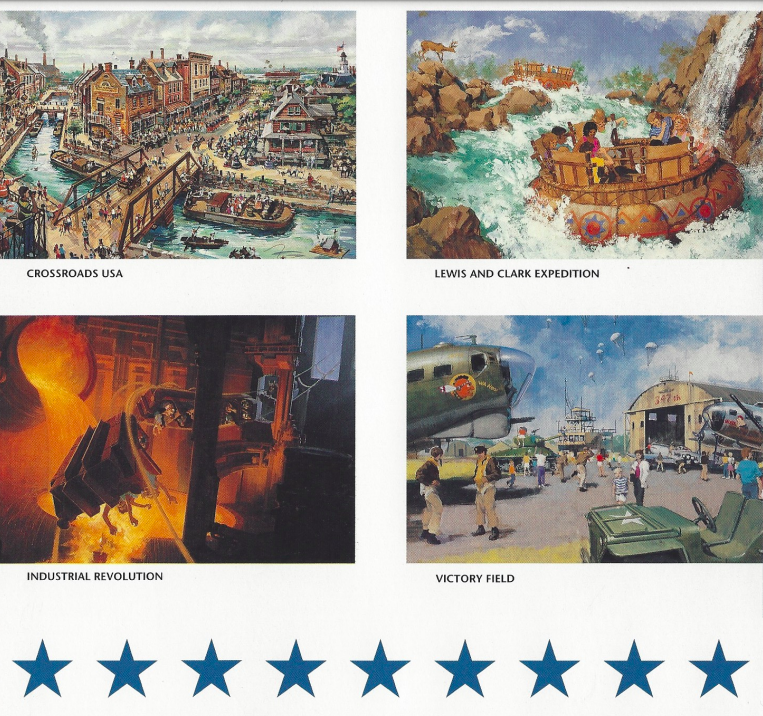

Having attracted the attention of Virginia residents and lawmakers, the press conference quickly turned into a sales pitch. The President of Disney’s Design and Development Department, Peter Rummell, relayed specific numbers to reporters, boasting that once the park opened in 1998, Prince William County would benefit from a growth in tourism, the creation of 3,000 permanent jobs, and $1.5 billion in tax revenue.[5] Initial park plans outlined blueprints for nine historically-themed areas over 1,200 acres unified under the park’s motto: “Recall the Past, Live the Present, Dream the Future”.[6] Officials passed around pamphlets that advertised catchy titles such as “Crossroads USA”, “President’s Square” and “Victory Field”.[7] Disney built up excitement by promising that visitors could expect to ride steam trains, shake hands with automaton Presidents, and operate tanks and weapons as participants in reenactments of major American battles.

Representatives indicated that unlike the fantasy elements of Disney’s other two amusement parks in Florida and California, Disney’s America would not shy away from the painful moments, including slavery and war, that were a part of America’s past. In their efforts to highlight the country’s diversity, Disney set aside places in the parks for exhibits centered on the immigrant experience, Native American culture, and the charms of small-town America. The park's major highlights were pitched as a Civil War Fort where guests could “experience the reality of a soldier's daily life” and an Industrial Revolution-themed rollercoaster that would speed through dangers of a steel mill.[8] Representatives told reporters that “we are hoping to really be a little controversial...and not be quite as nice and sweet as [Disney parks] may have been in the past”, however they still promised to include popular characters like Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck throughout the park.[9]

Even as they wished on Virginia’s brightest stars, Disney officials still needed to secure licenses and zoning approvals to begin the park’s construction. They appealed to state politicians by insisting that Disney’s America would be the “long-running economic engine for Prince William County and the Commonwealth of Virginia.”[10] Enchanted by the economic promises Disney claimed they could make appear with building permits and some pixie dust, Virginia’s Governor George Allen hoped to make the magic happen as the company’s fairy godmother in Richmond. Allen eagerly expressed his support of the project by telling reporters,

“I think it’ll be a moneymaker for the state...Our administration will certainly kick down any hurdles.”[11]

While lawmakers were in wonderland, mayhem brewed among residents, environmental groups, and local historians who voiced their growing opposition for Disney’s America. Locals challenged Disney’s claim that the park would be an economic success by pointing to the negative effects the park would have on surrounding infrastructure and quality of life. They argued that Disney’s America would require millions of dollars to improve roads and transportation infrastructure, while increasing traffic and pollution along Interstate-66.[12] The potential for urban sprawl threatened to radically transform the peacefulness of Prince William County’s lush fields and meadows into concrete landscapes dotted with fast-food restaurants, gas stations, and strip malls.

Environmentalists criticized Disney for not guaranteeing the protection of wetlands and native wildlife. Meanwhile historic preservation groups listed Haymarket as an endangered historic area and argued that Disney “could forever spoil land that is inextricably bound to America’s history.”[13] Disney responded to the social and environmental appeals by promising to incorporate recyclable and energy efficient materials into the park but ultimately expressed that “so-called suburban sprawl [was] not their responsibility.”[14]

Beyond development of the land itself, there were other, more philosophical, concerns. Disney America’s deviation from the company’s fantasy formula worried historians who questioned the park’s ability to accurately portray historical events. The company’s emphasis on creating an entertaining family experience while simultaneously presenting painful subjects increased fears over the dangers of simplifying history.

President of the National Trust of Historic Preservation, Richard Moe, expressed his concerns in the Washington Post asking readers to question, “what will ‘Disney's America’ mean for the teaching of American history? How authentically will Disney portray the awfulness of slavery or the brutality of the Indian wars?”[15] Those with insider access to Disney’s plans noticed that creators paid close attention to the park’s aesthetics, working out the smallest visual details including the buttons on soldiers' uniforms, but ultimately lacked nuance and sensitivity when they approached heavier historical subjects. Historian Cathleen Magennis Wyatt commented in the New York Times that “they had not addressed slavery at all...the park looked extraordinarily Anglo-Saxon.”[16] At the same time, some worried that Disney’s America would pull visitors away from “authentic” history sites, including the Manassas Battlefield and Mount Vernon, which would struggle to compete with the lights, animation, and technology that made Disney…well, Disney.[17]

A group of preservationists and historians including Shelby Foote, Barbara Fields, and Ken Burns formed Protect Historic America to organize and push back against the new park. Foote turned down an opportunity to consult as a historian with Disney arguing publicly that he could not participate in the creation of artificial history as “Disney’s specialty is to sentimentalize everything it touches.”[18] The simplification and romanticization of American history threatened to distort understandings of the Civil War and slavery in a way that Ken Burns described as “sanitizing and making ‘enjoyable’ a hugely tragic moment of our past.”[19]

There were some academics who suggested that Disney’s America could popularize history in a way that engaged people who would otherwise have no interest in learning about America’s past. Eric Foner, a history professor at Columbia University, worked for Disney as a project consultant and stated in an interview that, "I am not opposed to the presentation of history in a popular manner as long as it's good history.”[20] The idea that there was only one right way to present history was argued to be elitist and inaccessible. Reporter David Stout of the New York Times responded to the alternate perspective by asking,

“At what point does the effort to make history accessible make it something other than history?”[21]

In response to escalating backlash, Disney stayed the course as long as it could. They found allies in local politicians and residents who yearned for the development of new entertainment spaces for their families and more tourist revenue in their small towns.[22] The company also made an effort to address some of the community’s grievances. Namely, officials agreed to a revised 500-page proposal that reduced the size of Disney’s America to only 405 acres and imposed noise, construction, and environmental regulations.[23]

These concessions were not enough to sway doubters, especially as some began to question the rosy economic forecasts, which had been attached to the new theme park. As Rudolph Pyatt Jr. from the Washington Post commented, “on paper at least, the Disney project doesn't appear to be the statewide economic blockbuster that many of its more ardent supporters, including Gov. George F. Allen, had suggested it would be.”[24]

In the end, the pushback was too much. Ever conscious of hits to the company’s image, Disney representatives flew to Richmond to hold an emergency meeting with Governor Allen where they officially informed him of their decision to step away from the project. Allen emerged from the almost two hour long meeting pushing past reporters as he rushed to the elevators that closed in front of his dismayed face.[25] As historians and environmental activists cheered in victory, it took local politicians some time to process their shock. In a late night press conference, Disney officials admitted that the national debate over the park's proposed location in Haymarket, Virginia was damaging the company’s reputation. Rummell told reporters,

"The controversy over building in Prince William County has diverted attention and resources from the creative development of the park...we recognize that there are those who have been concerned about the possible impact of our park on historic sites in this unique area...While we do not agree with all their concerns, we are seeking a new location so that we can move the process forward."[26]

Far from a fairytale ending, some residents found a silver lining to Disney’s decision to abandon its plans for the theme park. Gainesville resident Linda Budreika told reporters, “I feel like a tremendous weight has lifted. I hope somehow the community can mend itself now. It’s been so divisive it has torn us apart.”[27] Before they left the state however, Disney vowed to return and someday bring their park to Virginia, leaving all of us to stay tuned for a sequel.

Footnotes

- ^ The Walt Disney Company, “Disney’s America Conceptual Site Plan: Celebrating America’s Diversity, Spirit and Innovation,” 1993.

- ^ Richard Turner and Tony Horwitz, “Entertainment: Disney and Academics Escalate Battle over the Entertainment Value of History,” The Wall Street Journal, June 21, 1994.

- ^ Michelle Singletary and Spencer S. Hsu, “Disney Says VA. Park Will Be Serious Fun,” The Washington Post, November 12, 1993.

- ^ The Walt Disney Company, “Disney’s America Conceptual Site Plan: Celebrating America’s Diversity, Spirit and Innovation.” 1993.

- ^ Richard Turner, “Disney Outlines Plan For a Theme Park At Site in Virginia --- Cost of Its Third Such Complex In the U.S. Is Said to Range To as Much as $800 Million,” The Wall Street Journal, November 12, 1993.

- ^ The Walt Disney Company, “Disney’s America Conceptual Site Plan: Celebrating America’s Diversity, Spirit and Innovation.” 1993.

- ^ The Walt Disney Company.

- ^ The Walt Disney Company.

- ^ Singletary and Hsu, “Disney Says VA. Park Will Be Serious Fun,” The Washington Post, November 12, 1993.

- ^ The Walt Disney Company, “Disney’s America Conceptual Site Plan: Celebrating America’s Diversity, Spirit and Innovation,” 1993.

- ^ Singletary and Hsu, “Disney Says VA. Park Will Be Serious Fun,” The Washington Post, November 12, 1993.

- ^ Paul Baker and Spencer S. Hsu, “Disney Gives Up on Haymarket Theme Park, Vows to Seek Less Controversial Virginia Site,” The Washington Post, September 29, 1994.

- ^ Michael D. Shear, “List of Imperiled Historic Areas Targets Disney; National Group Deplores Proposal to Develop Theme Park in Rural Virginia Piedmont,” The Washington Post, June 15, 1994.

- ^ Shear.

- ^ Richard Moe, “Downside to ‘Disney’s America,’” The Washington Post, December 21, 1993.

- ^ Turner and Horwitz, “Entertainment: Disney and Academics Escalate Battle over the Entertainment Value of History,” The Wall Street Journal, June 21, 1994.

- ^ Moe, “Downside to ‘Disney’s America.’” The Washington Post, December 21, 1993.

- ^ Turner and Horwitz, “Entertainment: Disney and Academics Escalate Battle over the Entertainment Value of History,” The Wall Street Journal, June 21, 1994.

- ^ David Stout, “Packaging America’s Killing Fields,” The New York Times, May 22, 1994.

- ^ Stout.

- ^ Stout.

- ^ Spencer S. Hsu, “Some Are Dreaming of a Magic Kingdom; Pr. William Officials Say Disney’s America Theme Park Could Be Magnet for Tourism,” The Washington Post, November 18, 1993.

- ^ Shear, Michael D. “Disney’s Theme Park Clears Another Hurdle; Pr. William Planners Recommend ‘America.’” The Washington Post. July 28, 1994.

- ^ Rudolph A. Pyatt Jr., “Disney’s New Theme Park Plan: It’s Not the Mouse That Roared,” The Washington Post, June 2, 1994.

- ^ Baker and Hsu, “Disney Gives Up on Haymarket Theme Park, Vows to Seek Less Controversial Virginia Site,” The Washington Post, September 29, 1994.

- ^ Baker and Hsu.

- ^ Lorraine Woellert, “Disney Drops Haymarket as Site for Park - New Virginia Location Sought,” The Washington Times, September 29, 1994.

![Small Arms Practice Six OSS recruits watch an instructor shoot a small arm during training at Chopawamsic's Area C. [Source: National Park Service]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2A8CB9F8-1DD8-B71C-070E22100840145DOriginal.jpg?itok=xboGo_08)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)