John Collier and the Indian Reorganization Act

Since the early nineteenth century, there have been multiple government attempts to organize Native Americans “so that the United States could formally deal with them.” Southeastern tribes were “encouraged” to create written constitutions in the 1830s that set up governments similar to the U.S. federal government. Over the next several decades, the Bureau of Indian Affairs urged tribes out west to do the same, and by the end of the 1880s, it“instituted both police and judicial institutions on the reservations.”[1] During this period the Dawes Act further assimilated tribes by instituting a land allotment policy that gave parcels of land to individual Natives that were formerly owned by tribal communities.[2]

By 1934, BIA Commissioner John Collier believed that land allotment and other policies meant to help Native Americans were doing more harm than good, and he wanted to reverse them through an ambitious bill known as the Indian Reorganization Act (also called the Wheeler-Howard Act). Collier’s bill would not only nullify the land allotment policy, but it would also allow Native American tribes to govern themselves, decentralize the BIA, consolidate Native land, and transfer Indigenous children from boarding schools to day schools.[3]

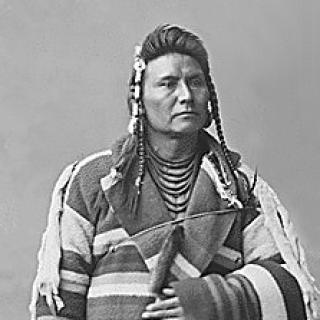

Prior to joining the Bureau in 1933, Collier did social work with the Taos Pueblo of New Mexico, and his time there touched him deeply. He later said, “[It was] an experience that reached from the deep soul of Indian life into all of my feeling and thinking mind .... I felt my own life had been changed by this earliest Indian experience and I felt a deep gratitude, but also a deep sadness. I felt that there was no hope for these dauntless people; that the gigantic past that lived in them must soon become an eternal silence, and the truly cosmic emotion that flooded their ritual expression must soon become an ebb-tide returning never.” Collier’s experiences with the Taos Pueblo along with his advocacy for Indigenous peoples throughout the 1920s shaped his view on Native American affairs and led him to draft the Indian Reorganization Act.[4]

To get outside input, Collier and other BIA high-ups met with around 50 representatives from some of the country’s major Indigenous welfare organizations on January 7, 1934. Matthew Sniffen, director of the Indian Rights Association, sent invitations to leaders of his organization as well as the National Association on Indian Affairs, the Indian Civil Rights Committee, and the American Indian Defense Association.[5] While these organizations purportedly had Native Americans’ best interests at heart, they were all founded and led by non-Natives, which surely affected their idea of what those interests were.[6] Supposedly, only the only Indigenous people at the conference were Capt. and Mrs. Bonnin (Nakoda) and Princess Chinquilla, a Cheyenne woman from New York “whose claim to Indian birth aroused Mrs. Bonnin’s skepticism.”[7] A pamphlet published by the American Indian Defense Association explained that, “The conference, which will be held at the Cosmos Club in Washington, is aimed at giving intensive consideration to the proposed legislation, and to provide an opportunity for exchange of opinion prior to its introduction.”[8]

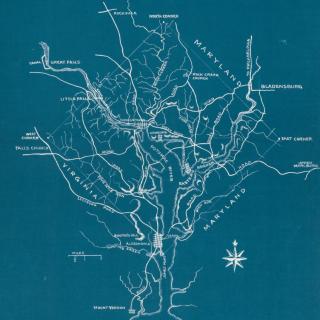

Founded in 1878 by explorer John Wesley Powell, the Cosmos Club was and still is one of Washington’s many private social clubs. Three weeks after the first meeting in Powell’s own home, its ten members agreed, "The particular objects and business of this association are the advancement of its members in science, literature, and art, their mutual improvement by social intercourse, the acquisition and maintenance of a library, and the collection and care of materials and appliances relating to the above subjects.”[9] While most other societies “tended toward specialization and formal meetings,” the Cosmos Club was meant to be a place where “influential men in the arts, sciences, and politics” could exchange ideas, and it became popular as a meeting venue for various cultural societies and organizations.[10]

As its membership list expanded, the Cosmos Club moved from the Corcoran Building at 15th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue N.W. to the Madison House in Lafayette Square in 1882. In 1930, just a few years before Collier’s conference, Congress “authorized, empowered and encouraged” the Secretary of the Treasury to acquire all the land on Madison Place to build government offices, but the January 1934 meeting still took place there since it would be another five years before the government made a solid offer for the property.[11]

The attendees arrived at the Club on the morning of January 7 for the conference which began at 9:30 a.m. Once a chairman was selected and an agenda was set, it was “unanimously agreed that opinions formulated or expressed by the conference would not bind the organizations represented and that all votes of agreement… would be subject to this reservation.”[12]

The bulk of the meeting was devoted to discussing Native self-government and land reform. Attendees were unanimously in favor of adopting the portion of the Act that dealt with self-government and agreed that tribes should gain more control over their own affairs by gradually transferring power from the BIA to Indigenous communities.[13] In addition, a unanimous vote decided that “the provisions of the allotment system which require or permit the transfer of Indian tribal lands to individual Indians and the sale of such lands by individual Indians to non-Indians shall be immediately repealed,” and that “a process of land acquisition be set up by which so far as feasible allotted lands will be restored to community ownership, especially forestry and grazing lands…”[14] In an interview with Vera Connolly for a piece in the Good Housekeeping magazine, Collier maintained, “This land reform is a prerequisite of all else. Without it we can do nothing lasting for the Indians. And surely there is no reform so clearly owed the Indians by the Government which has forcibly deprived them of their lands.”[15]

Finally, at 10:15 p.m., “The conference adjourned unanimously adopting a resolution pledging the various participating organizations to aggressive support of the proposed legislation, upon its endorsement by their respective boards of directors.”[16] The Washington Post noted that the January 7 conference was “the first time that organizations dealing with Indian interests have been in agreement upon a policy,” and Indian Rights Association director Matthew Sniffen wrote later that month that he was surprised at the result of the meeting, considering the “variety of thought” among the different groups represented, but he was “much pleased” at what they decided upon.[17] About 90% of Collier’s proposed bill was received favorably at the Cosmos Club, and according to the commissioner himself, that happened because “The agreed-on program as it now exists is [not]... one-sided…. At this time, as I think you will agree, the program does see “Indian life steadily and whole.””[18]

However, there was still a lack of Native American input, which Collier didn’t act upon until one of the attendees and drafters of the Act, Felix Cohen of the Department of the Interior, pointed it out shortly after the conference. In a memo addressed to Collier, Cohen wrote on January 17, “...without considerable Indian support our legislative program is not likely to meet a favorable reception in Congress.”[19] Cohen suggested that Collier distribute an outline of the Bill to Native tribes similar to the one sent to the Indigenous welfare groups before their meeting at the Cosmos Club. After doing so and receiving mixed responses from tribal leaders, the Commissioner held a series of regional conferences with groups of Native Americans.[20] Although “It was not expected that the Indians would commit themselves to the bill...they were to go and listen to what was said; then go home and report to their respective tribes on the proposition for further consideration.”[21] Unlike the representatives at the Cosmos Club, the attendees of the regional meetings left with opinions that were “far from being unanimous.”[22]

Some were hopeful, believing that the change would benefit tribal communities. As Edward Quick Bear (Rosebud Sioux) reasoned, “The old way leads to the end of the trail. We can lose nothing by trying the new way.”[23] In a similar vein, Albert Hart of Nebraska (Winnebago) explained, “Our 800,000 acres have dwindled to 25,000. Nothing could be worse than the old way.”[24]

On the other hand, there were those who were skeptical of the Act. Harry Whiteman (Crow) admitted, “I have been called the most ungrateful Indian in the United States, but I cannot be silent. I have been told the commissioner’s heart is in this bill. I also have a heart, and my heart is with the welfare of my people…. This should not be passed unless agreed upon by a three-fourths vote of all the Indians of the United States.”[25]

Despite the mixed reactions from Native Americans, on June 18, 1934, President Roosevelt signed the bill, turning the Indian Reorganization Act into law. Collier called the day “the Independence Day of Indian history,” adding, “It is in their power to make of the new Act a foundation stone and an open door to a great future.”[26] They had that power because the bill gave each tribe the choice to either include or exclude themselves from its policies. Once again, Native responses were not unanimous. By June 1935, 172 tribes had voted to be included and 73 had voted to be excluded.[27]

Similarly, when its policies were enacted, opinions on the Indian Reorganization Act varied depending on whom you asked. In a 1970 interview, Sioux tribal leader Alfred Dubray said, “It had a lot of advantages that many of the people didn’t see, such as making loan funds available, huge amounts of that. Farm programs were developed through this. Cattle-raising programs were initiated. Educational loans were beginning to be made available for Indian youngsters who had never had any opportunities before, hardly, to attend any higher institutions.”[28]

Others thought the Act ended up doing more harm than good. According to attorney Ramon Roubideaux (Brule Sioux), “...what this Indian Reorganization Act should have done, it should have set up a county system exactly like the neighboring counties, with county officials, with municipal officials, with Indians going about their daily political and economic activities in the same way that other people in the state are, so that they could benefit from...becoming part of the mainstream of American life.”[29]

Both before and after the Indian Reorganization Act was passed, Indigenous reactions to the bill were far more varied and nuanced than those of the attendees at the Cosmos Club meeting who represented white-led Native welfare groups. While the conference allowed Collier to present the initial draft of the Act, perhaps he should have listened more closely to those who would be affected.

Footnotes

- ^ Vine Deloria, Jr. , The Indian Reorganization Act: Congresses and Bills (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002), viii.

- ^ Lawrence C. Kelly, “The Indian Reorganization Act: The Dream and the Reality,” Pacific Historical Review 44, no. 3 (August 1975): 293.

- ^ Pfouts, “Senator Burton K. Wheeler and the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act,” (Master’s diss., University of Montana, 1981), 31.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ United States Congress, House, Hearings (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1939), 409. Alice Beck Kehoe, A Passion for the True and Just: Felix and Lucy Kramer Cohen and the Indian New Deal (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2014), 71.

- ^ Pfouts, “Senator Burton K. Wheeler,” 38.

- ^ Kehoe, A Passion for the True and Just, 71.

- ^ United States Congress, House, Hearings, 409.

- ^ Paul H. Oehser, “The Cosmos Club of Washington: A Brief History,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 60/62 (1960-1962): 254.

- ^ Lee D. Baker, Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 246. “History of the Cosmos Club,” Cosmos Club Washington, D.C., 2021, https://www.cosmosclub.org/History.

- ^ Oehser, “The Cosmos Club of Washington,” 261.

- ^ United States Congress, House, Hearings, 409-10.

- ^ United States Congress, House, Hearings, 411.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ United States Congress, Congressional Record (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1934), 5570.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Mr. Collier’s Policy,” Washington Post, January 9, 1934, 8. The Aggressions of Civilization: Federal Indian Policy Since the 1880s, ed. Sandra Cadwalader & Vine Deloria, Jr. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984), 36.

- ^ “Mr. Collier’s Address,” Indian Truth, January 1934, 2.

- ^ Elmer R. Rusco, A Fateful Time: The Background and Legislative History of the Indian Reorganization Act (Reno: University of Nevada Press), 211.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Indian Sentiment,” Indian Truth, April 1934, 1.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Pfouts, “Senator Burton K. Wheeler,” 61.

- ^ Lawrence C. Kelly, “The Indian Reorganization Act: The Dream and the Reality,” 301.

- ^ “It Had a Lot of Advantages”Alfred DuBray Praises the Indian Reorganization Act,” History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, George Mason University, accessed December 1, 2021, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/33.

- ^ “It Set the Indian Aside as a Problem”A Sioux Attorney Criticizes the Indian Reorganization Act,” History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web, George Mason University, accessed December 1, 2021, http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/76.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)