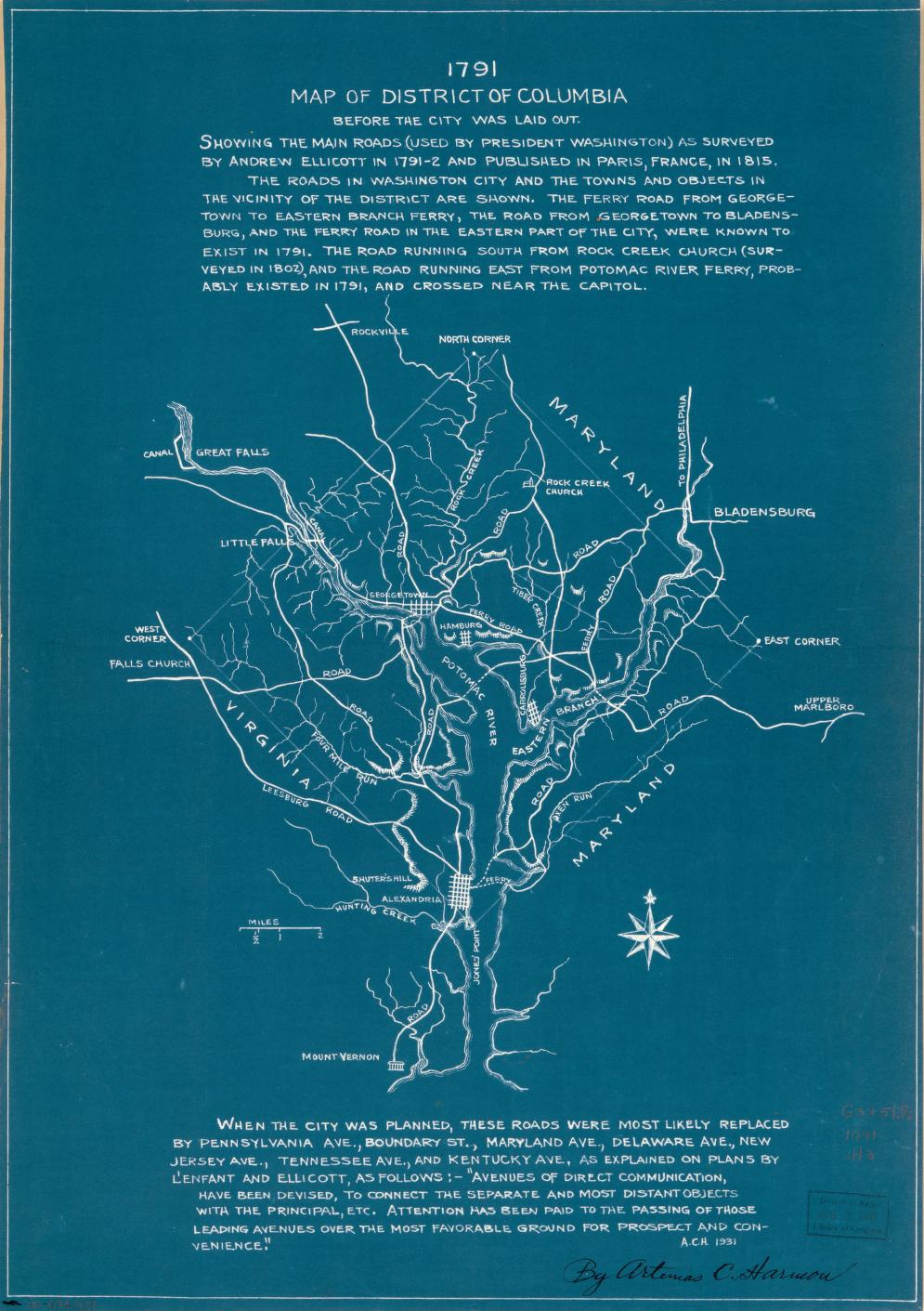

What a 1791 Map Reveals About D.C.'s Oldest Roads

Before its wide avenues and grand circles, the District of Columbia was a tiny territory surrounded by country farmland, with long dirt roads providing access to larger cities—places like Bladensburg, Frederick, Alexandria, or Georgetown—or to local plantations and homesteads.1, 2

In 1790, cartographer Andrew Ellicott was commissioned to survey the existing roadways and topography in the land that would become the District of Columbia, before the construction of Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s elaborate city plan.3 The survey was carried out with assistance from Benjamin Banneker, the free Black astronomer, mathematician, and urban planner who worked as Ellicott’s assistant throughout the Capital planning process.4

The resulting map, later complied in 1815 by A.C. Harmon, reveals the byways that Washington’s first residents built, and what lies under our modern artistic and painstakingly planned street system. It shows what could be the oldest roads in D.C., standing or demolished; the paths that led to what were then hubs of commerce, transportation, and worship. They reveal the central facets of early Washington life which busy D.C. residents no longer orbit, but whose trails we certainly follow.

Bladensburg Road

During the 18th Century, what is now the Maryland suburb of Bladensburg was a bustling port city, vital for its position on the tobacco trade route along the Anacostia River. At the time of European colonization of Maryland, Indigenous people were settled closely to the territory that became Bladensburg, known as the “Nacotchtank,” meaning “at the trading town” or “a town of traders.”5, 6 The term was later anglicized into the modern "Anacostia."

Bladensburg’s busy port made it a strategic location, and during the War of 1812 it was captured by British troops. The road on which British Colonel Thornton travelled to seize and burn the Capitol still stands today, and we know it as Bladensburg Road.7

Kenilworth Avenue

Before it was known as Kenilworth Avenue, the street that travelled along the southern bank of the Anacostia River towards Bladensburg was known as Eastern Branch Road or Eastern Branch Ford in the 18th Century.8, 9, 10 Prior to European colonization, the Eastern bank of the Anacostia River was inhabited by Indigenous people.11, 12 Upon European occupation and the construction of Eastern Branch Road (future Kenilworth Avenue) on top of these former settlement sites, a vestige of the Nacotchtank people’s lives and practices remained—Minnesota Avenue, which runs partially parallel to Kenilworth—encompasses a portion of a Nacotchtank passage that was called “Piscataway Road” by settlers in the 1700s.13

Florida Avenue

Today’s Florida Avenue doesn’t adhere to the exact path that’s marked on Ellicott’s map. But its Western trajectory and downward slope as it connects with Sherman Avenue Northwest follows the direction of a road that Ellicott charted.

Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s design plan for D.C. halted at the modern Florida Avenue.14 As the city developed, “Boundary Street” became an unofficial border between downtown D.C. and more rural Washington County, before the entire city was incorporated.15

On Ellicott’s map, the road breaks from the modern path after its southward dip and then continues East, and so was known as another “Road to Bladensburg.”16 George Washington was said to have travelled this road on his way back-and-forth to Bladensburg and D.C. from Mount Vernon.17

Rock Creek Church Road

Although fragmented and unassuming today, Rock Creek Church Road is arguably the oldest continuously named street in the District.18 While other roads that appear on Ellicott’s map may have existed before the establishment of Rock Creek Church, those streets have gone through multiple identity changes as their uses shifted and they were absorbed into the D.C. street naming system.

St. Paul’s Rock Creek Church is one of the oldest standing city institutions—founded in 1712 and established on its current site in 1721,19 the church has supported a dedicated parish community for over 300 years. The church itself is the only building named on Ellicott’s map---even in his time, it was a well-known religious community that had flourished for decades.

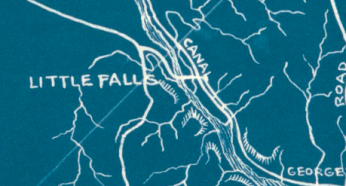

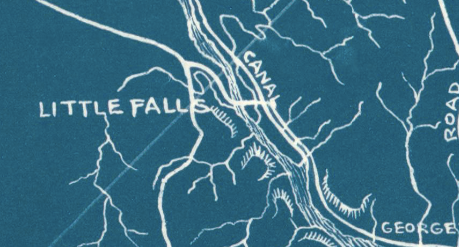

Canal Road

Canal Road follows the Northern bank of the Potomac River along what is now the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. However, before the C&O was completed in the early 19th century,20 there was another manmade waterway that stretched across the Potomac River and into D.C. territory, just near Little Falls.21, 22 ; Planned in 1789 under orders from George Washington, it was known as the Pawtomack Canal.23

The road marked on Ellicott’s map runs along the Little Falls Canal, a small section of the Pawtomack that was likely useful for transporting goods in and out of Georgetown. It was officially completed in 1795.24 The road that follows it is still in use today and runs along the historic banks of the Potomac River into Maryland, becoming Clara Barton Parkway.

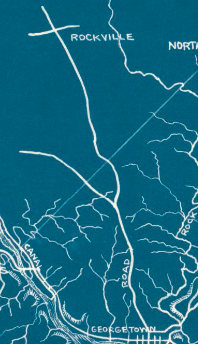

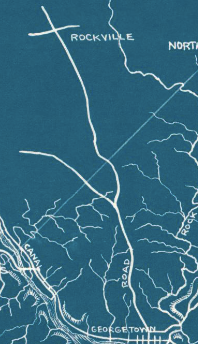

Wisconsin Avenue

Wisconsin Avenue is likely the oldest road in the District of Columbia—that’s because it wasn’t first walked by people, but by prehistoric megafauna migrating seasonally to the banks of the Potomac River (yes, really). The major artery of Northwest D.C., Wisconsin Avenue has been continuously in use for thousands of years.25 After the last Ice Age, when Bison moved on from the District to the prairies of the West, Nacotchtank people utilized the high ridge of the road for trade and travel, and its terminus in Georgetown was the site of a village known as Tahoga.26 The road was also marked, unnamed, on a 1712 map as travelled by Swiss Baron Cristoph De Graffenried.27 Before its modern name, the street had been called by many titles depending on who was walking it---Fredericktown Road, High Street, Water Street, Tennally Road---until being officially named Wisconsin Avenue in 1905.28

D.C. life has changed over the past three centuries—and the locations that Washingtonian life revolves around are constantly shifting. But the roads that D.C. residents travel on can serve as evidence of the communities that existed before us, and the ways that they continue to maintain presence in the city today.

Footnotes

- 1

“Washington, D.C. - Capital, Founding, Monumental," Britannica. August 7, 2024.

- 2

Harmon, A.C. “1791 Map of District of Columbia, before the City Was Laid out : Showing the Main Roads (Used by President Washington) as Surveyed by Andrew Ellicott in 1791-2 and Published in Paris, France, in 1815.” 1815. Image.

- 3

White House History. “Benjamin Banneker.” Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 4

"Africans in America, Benjamin Banneker," PBS. Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 5

Hedgpeth, Dana. “A Native American Tribe Once Called D.C. Home. It’s Had No Living Members for Centuries.” The Washington Post, November 22, 2018.

- 6

“Battle of Bladensburg - History.” Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 7

- 8

Ellicott, Andrew. “Territory of Columbia.” 1794. Image. Library of Congress.

- 9

Burr, Charles R. “A Brief History of Anacostia, Its Name, Origin and Progress.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 23 (1920): Page 170.

- 10

Rowlands, DW. “Here’s How Neighborhoods West of Kenilworth Avenue in Northeast DC Became Isolated from the City.” Greater Greater Washington (blog), July 22, 2021.

- 11

U.S. National Park Service. “Native Peoples of Washington, DC,” January 10, 2018.

- 12

Mason, Otis T., W J McGee, Thomas Wilson, S. V. Proudfit, W. H. Holmes, Elmer R. Reynolds, and James Mooney. “The Aborigines of the District of Columbia and the Lower Potomac - A Symposium, under the Direction of the Vice President of Section D.” American Anthropologist 2, no. 3 (1889): Page 242.

- 13

Burr, Charles R. “A Brief History of Anacostia, Its Name, Origin and Progress.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 23 (1920): Page 170.

- 14

L’Enfant, Pierre Charles. “Plan of the City Intended for the Permanent Seat of the Government of t[He] United States : Projected Agreeable to the Direction of the President of the United States, in Pursuance of an Act of Congress, Passed on the Sixteenth Day of July, MDCCXC, ‘Establishing the Permanent Seat on the Bank of the Potowmac.’” Image. Library of Congress, 1991.

- 15

DC Preservation League. “Tour | Following Florida Avenue: The Original Boundary of the City of Washington.” DC Historic Sites. Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 16

Ellicott, Andrew. “Territory of Columbia.” 1794. Image. Library of Congress.

- 17

Hagner, Alexander B. “Street Nomenclature of Washington City.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 7 (1904): Pg 257-258.

- 18

Park View, D.C. “Could Rock Creek Church Road Be D.C.’s Oldest Street?,” December 18, 2013.

- 19

St. Paul’s Rock Creek Episcopal Parish. “Our History.” Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 20

Georgetown Heritage. “Canal History.” Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 21

Lizars, WH. “Plan of the City of Washington and Territory of Columbia / Engraved by W. & D. Lizars, Edin’r.” Image. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Accessed August 14, 2024.

- 22

22 Ellicott, Andrew. “Territory of Columbia.” 1794. Image. Library of Congress.

- 23

U.S. National Park Service. "Chronology of the Great Falls.” July 28, 2021.

- 24

Hahn, Thomas F. Towpath Guide to the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal : Georgetown Tidelock to Cumberland. Shephardtown, WV: American Canal and Transportation Center, 1996. Page 22.

- 25

Fletcher, Carlton. "A Brief History of Wisconsin Avenue." Glover Park History. Accessed June 4, 2024.

- 26

Levin, Johnathan V. “Old Georgetown Road: A Historical Perspective.” Montgomery County Story 45, no. 2 (May 2002). Pg 226.

- 27

Levin, Johnathan V. “Old Georgetown Road: A Historical Perspective.” Montgomery County Story 45, no. 2 (May 2002). Pg 227.

- 28

Fletcher, Carlton. "A Brief History of Wisconsin Avenue." Glover Park History. Accessed June 4, 2024.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)