The City That Was... And The City That Never Was: A Tale of Two Paintings at the GW Museum

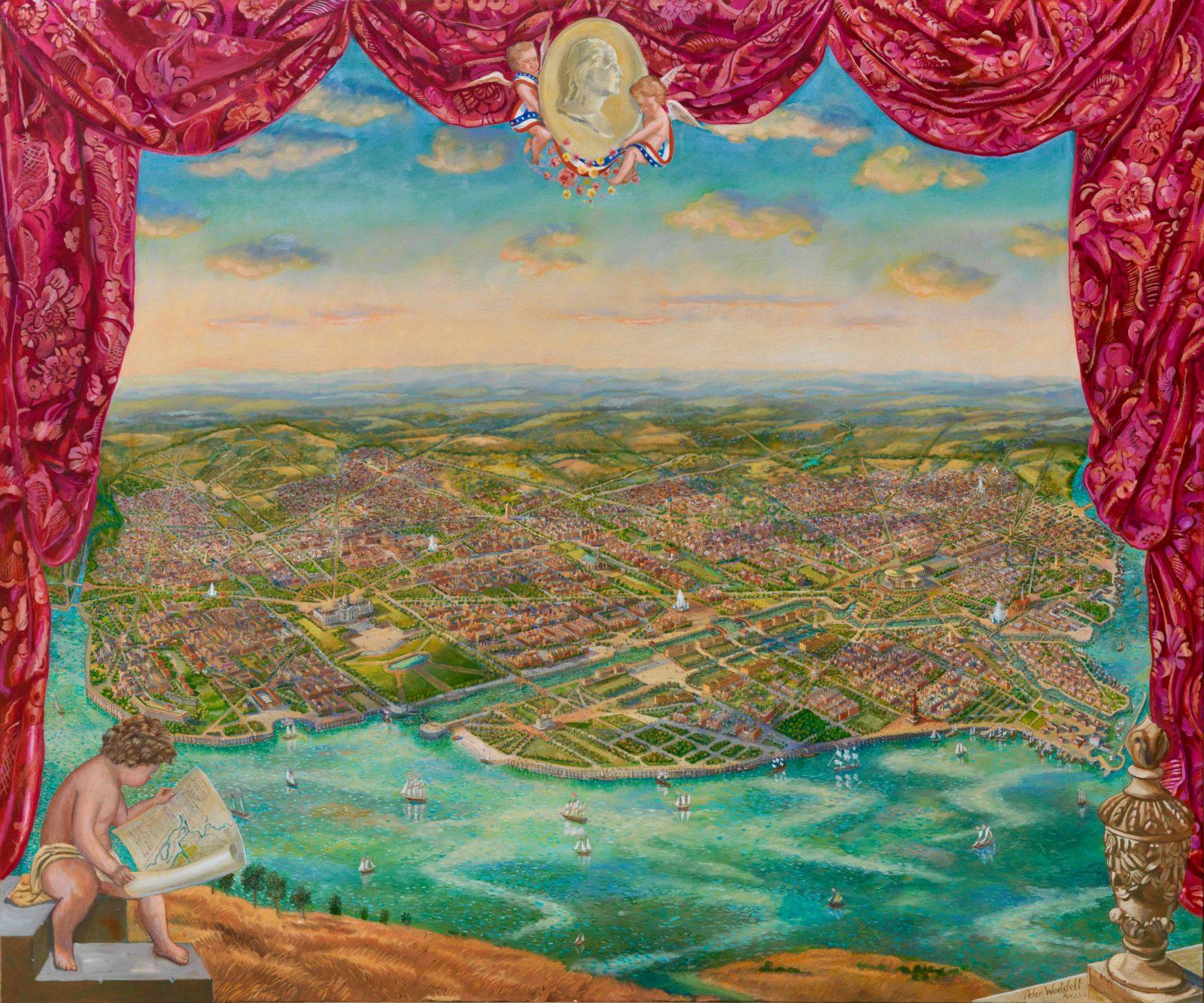

Walk up the spiral staircase at the George Washington University Museum, take a right into the first gallery, and you will be met with a pair of large (5’ x 6’) bird-eye's-view paintings of Washington, DC. [1] Both represent the capital city in the 1820s and, at first glance, the two works look very similar, with comparable coloring, landscape, and style.[2] That’s not surprising as both were done by the same artist and, significantly, the two pieces share the same view – looking down on the District from Arlington Heights.[3]

Taken together the paintings are among the most accurate representations of the planned actual federal city which exist to date.[4] But, upon closer examination, it becomes clear that the paintings represent different perspectives of the fledgling national Capitol – one aspirational, the other more realistic – and both can teach us a lot about D.C. history.

“The Indispensable Plan: 1791”

The first painting, entitled “The Indespensable Plan 1791,” depicts the design envisioned and outlined by the District's planner and architect Pierre L'Enfant, much of which was never actually constructed.[5] The colors are vibrant, and a cherub sits in the foreground holding what appears to be a map or building plans. The painting is framed by painted curtains, lending the viewer familiar with art history the insight that the image is fictional in nature.

While there are plenty of the expected landmarks of Washington, the painting also contains other unfamiliar aspects, including a grandiose palace that looks like it belongs somewhere in Europe.[6] Then, there are small town squares with even smaller statues dotting the cityscape. While they look similar to the various traffic circles of modern-day DC, L’Enfant had something else in mind beyond the constant flow of traffic; instead, he wanted each of the original thirteen states to be given a section of the city with a town square.[7] The idea was that individuals moving to the District would settle in the part of DC, which corresponded to their home state.[8] The residents of the state-based neighborhood would then have the ability to erect a monument within their town square to a hometown hero or something representing their state of origin.[9]

L’Enfant was well-intentioned; he wanted to promote equal development of the city and thought encouraging people from the same state to live in the same neighborhood would do just that.[10] As we know today, though, this plan never left the pages of the design manuscript. For starters, it is hard to predict human behavior.[11] Furthermore, it would have been difficult for to account future states, which were added to the Union.

“The Village Monumental: 1825”

The second painting, “The Village Monumental,” depicts what the city actually looked like at the time of L'Enfant’s death in 1825.[12] The scene probably seems a bit more familiar to most Washingtonians. Pictorial representations of the White House, the nineteenth-century equivalent of the Key, Memorial, and Fourteenth Street bridges, and the grid system with diagonally bisecting avenues that meet at various points throughout the piece decorate the painting. While the colors are more muted than in “The Indispensable Plan,” there is far more life, as illustrated by the abundance of people in the foreground and scattered throughout the streets.

The Process

But how did these two works of art come to be? We can thank DC real estate mogul Albert H. Small for conceiving and commissioning this pair of paintings. “His dad started as a developer, and then he got into it as well, which is why we have so many maps,” said Jackie Streker, the current curator of the Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection.[13] “Almost a third of our collection is maps. I think that really spoke to him as a real estate guy to see where the city was growing and what was building out of it. And to see its growth.”[14] With one of the largest collections of historic DC maps, Albert Small wanted a way to distill the fruit of his over sixty-year labors into just one or two pieces.[15]

With an idea in mind, a ninety-year-old Small embarked on a journey to find just the right artist to bring his vision to light.[16] Quickly, the name of a painter he met at an art gallery in the 1990s popped into his head.[17] Peter Waddell, a painter of historic scenes, was just the right man for the job.[18] Not only did Waddell have a background in completing commissions for other DC historical institutions like Mount Vernon, but he was also the artist in Residence at Tutor Place, a historic site devoted to bringing history to life.[19]

For such a large-scale task, Waddell recruited a young research assistant named Jackie Streker (yes, the same one who is now curator of the Washingtoniana Collection) to aid him in ensuring the paintings maintained the utmost manner of historical integrity.[20] The two painstakingly researched what the DC landscape would have looked like in both the envisioned and historic reality pieces.[21] For the first piece, the pair was permitted to view L’Enfant’s original plan at the Library of Congress — a rare occurrence. Waddell represented existing parts of the city—such as Georgetown— in the piece but took a small degree of creative liberty when bringing L’Enfant’s plans to life.[22]

“The Village Monumental 1825,” on the other hand, involved more traditional forms of fact-finding to portray such an image accurately. Waddell and Streker utilized vital pieces in Albert Small’s Washingtoniana Collection for the bulk of their research.[23] For example, an early nineteenth-century City Guide book of Washington, DC proved to be an invaluable primary source. It gave a block-by-block description of most of the city.[24] The duo could thus determine down to the building the type and look of almost every structure.[25] As a nod to the indispensable guidebook, the little boy in the foreground of the painting holds a pictorial representation of the actual guidebook in the Washingtoniana Collection.[26]

In addition to the physical look of the city, Waddell and Streker used the collection’s maps to inform the perspective of the paintings.[27] The most commonly used vantage point for birds eye’s view drawings of the District looks out west from the Capitol over the National Mall.[28] Waddell decided against this view as it would have cut out the entire eastern half of the city from inclusion in his paintings.[29] Continuing to sift through the folders of original maps, Waddell and Streker came across the Arlington Heights bird’s eye view images. Such a perspective allowed the entirety of DC to be depicted.[30]

For details which could not be gleaned from the Washingtoniana Collection, Waddell and Streker took advantage of other institutions and their research. For example, Waddell and Streker went to the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum to determine what kinds of dresses and accessories women living in 1825 would have worn.[31]

After two years of meticulous research and detailed painting, Waddell finished both paintings in 2018.[32] They hung in the Washingtoniana Collection space at the George Washington University Museum for a year.[33] Due to other exhibitions the museum planned to mount; the paintings were taken down and placed in storage. Over the next twelve months, many visitors expressed disappointment that the museum removed the pictures for public view.[34] Recognizing the public’s interest in seeing the paintings in person, the GW Museum added them to the permanent gallery space.[35]

Four years after their debut, visitors still come to the museum with the sole intent of viewing Waddell’s breathtaking works, and the future of the exhibit seems secure.[36] Per Streker, “Those paintings will remain. We’re also hoping to create educational programming around them to bring in school groups as they’ll remain in relative perpetuity. And they’re great entrances into whatever else we might have on display.”[37]

“The Indispensable Plan” and “The Village Monumental” may not be antique works of art, but they, in many ways, tell us more about the past of this historic city than most older artworks. Through the lens of time and space from the events depicted in these pieces, we can appreciate the plan laid out by L’Enfant. Simultaneously, we can love the way mankind strays away from the outline to create a place that was not just the product of one historic architect but also the result of the people, environment, and events that make DC history uniquely its own. Take an hour or so to pop by the GW Museum and see these unbelievable paintings which put any and all research papers to shame.

Footnotes

- ^ “Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection,” peterwaddell.com, Peter Waddell, accessed May 25, 2022, http://peterwaddell.com/commissions/albert-h-small-washingtoniana-collection/.

- ^ Jackie Streker (Curator of the Washingtoniana Collection) in discussions with the author, May 25, 2022.

- ^ “Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection,” peterwaddell.com.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Albert H. Small Washingtoniana Collection,” peterwaddell.com.

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ John Kelly, “A Capital Collection at GWU Showcases Traces of Washington's Past,” The Washington Post (Washington, DC), September 19, 2016.September 19, 2016.

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Biography,” peterwaddell.com, Peter Waddell, accessed May 25, 2022, http://peterwaddell.com/biography/.

- ^ “About Tutor Place,” tutorplace.org, Tutor Place, accessed May 31, 2022, https://tudorplace.org/about/our-story/.

- ^ Interview with Jackie Streker.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Ibid.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)