On a Wing and a Prayer: D.C.’s Destined-to-Fail Airmail Flights

On May 6, 1918, Major Reuben Fleet was at work in his Washington office when he was called in for an unexpected meeting with Secretary of War Newton D. Baker.1 Having just earned his wings the previous year, Major Fleet was relatively new in his career as a military pilot.2 The First World War was in full swing, and the Major was in charge of training inexperienced Army men to fly in France. Perhaps that was what this meeting was about – the war that was raging on in Europe? Or perhaps it was about his training program in general, and developments in aerial warfare?

The answer, Fleet soon found out, was neither. Secretary Baker wanted Major Fleet to head the United States Post Office Department’s first regularly scheduled airmail service, inaugurating the flights that would go between Washington, Philadelphia, and New York.3 With the newness of air travel, the Post Office would receive help from the Army, including the use of military aircraft and Army manpower.4

Major Fleet couldn’t believe his ears. “I was dumbfounded,” he later said. “I didn’t know how to tell this man who knew nothing about airplanes that he was giving me an almost impossible task. I said, ‘Mr. Secretary, with all due respect, we don’t have any airplanes that can fly from Washington to Philadelphia to New York.’”5 To Major Fleet, this entire endeavor was destined for failure, right from the start. To Secretary Baker, it was something that had to be accomplished, because Postmaster General Albert Burleson had already promised that airmail flights would commence and set May 15th – a mere nine days away – as the official start date.6

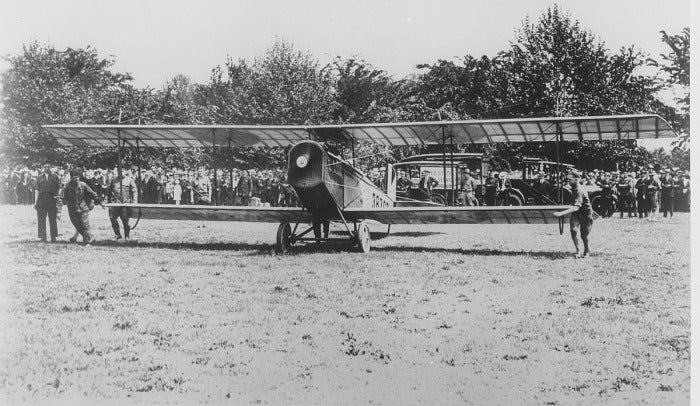

Before he even left Secretary Baker’s office, Major Fleet got on the phone and called Curtiss, an airplane manufacturer.7 There were two things he knew he needed to make this successful: good machinery and good pilots. Unfortunately, he had very little to choose from. The best plane he could think of was the Curtiss JN-6H, also known as the “Jenny”.8 While there were more advanced planes being used in the war, the Jenny remained the most popular model because it was easy to mass produce. The plane itself was rudimentary, even by 1918 standards, however, its availability made it so appealing to the Army, and for this endeavor in particular.9 Primarily used for training, the plane had dual controls for students and instructors and limited storage space. With military leadership breathing down his neck, Major Fleet ordered that some major modifications be made to the airmail delivery planes, like having the seats taken out to make room for mail cargo and expanding the gas tank to allow longer-distance flights.10 With the alterations, the Jenny’s top speed and range increased.11

But even if the planes worked perfectly, they would still require pilots with great ability. The entire endeavor required six pilots, with four flying at a time. Major Fleet was allowed to pick four of the six, with the Post Office selecting the other two. Choosing his pilots according to skill, Major Fleet chose Lieutenants Howard Culver, Torrey Webb, Walter Miller, and Stephen Bonsal.12 However, he soon realized that the Post Office did not employ the same criteria in selecting their candidates, and that’s where our story takes a real nosedive. (Pun intended.)

The Post Office Department selected Lieutenants James Edgerton and George Boyle. While both were military men who had earned their piloting wings, neither had the experience required for the airmail flights.13 But what they did have were personal connections.

James Edgerton’s father was a purchasing agent for the Department, while George Boyle’s soon-to-be father-in-law, Charles McChord, was an Interstate Commerce Commissioner who had protected the parcel post for the Post Office Department from falling into the hands of private companies.14 In other words, they were deeply invested in making the Post Office’s airmail deliveries a success.

George Boyle was selected to make the inaugural long-distance flight from Washington to Philadelphia, even though he had barely flown out of sight of his training field. Distressed, Major Fleet attempted to argue with this selection, but nepotism proved to be a formidable opponent. He ultimately conceded, and once again set out trying to make the impossible happen, while hoping for the best.

And this hope was certainly tested. Two days before the inaugural flight was supposed to take place, Major Fleet traveled to New York to the Curtiss Factory with five of the six pilots set to make the flights. The mail planes were reportedly ready, but by the afternoon of May 14th, only two of the six planes had been modified to the outlined specifications necessary for the airmail trips.15 Commenting later, Fleet remarked, “There were so many things wrong with the modified planes and their engines that we worked all night to get them in safe flying condition. One gas tank had a large hole in it, and we plugged it up with an ordinary lead pencil.” Alas, these were the cards Fleet had been dealt, so he made his way back to Washington, making multiple stops to refuel and set the other pilots up in their designated cities.16

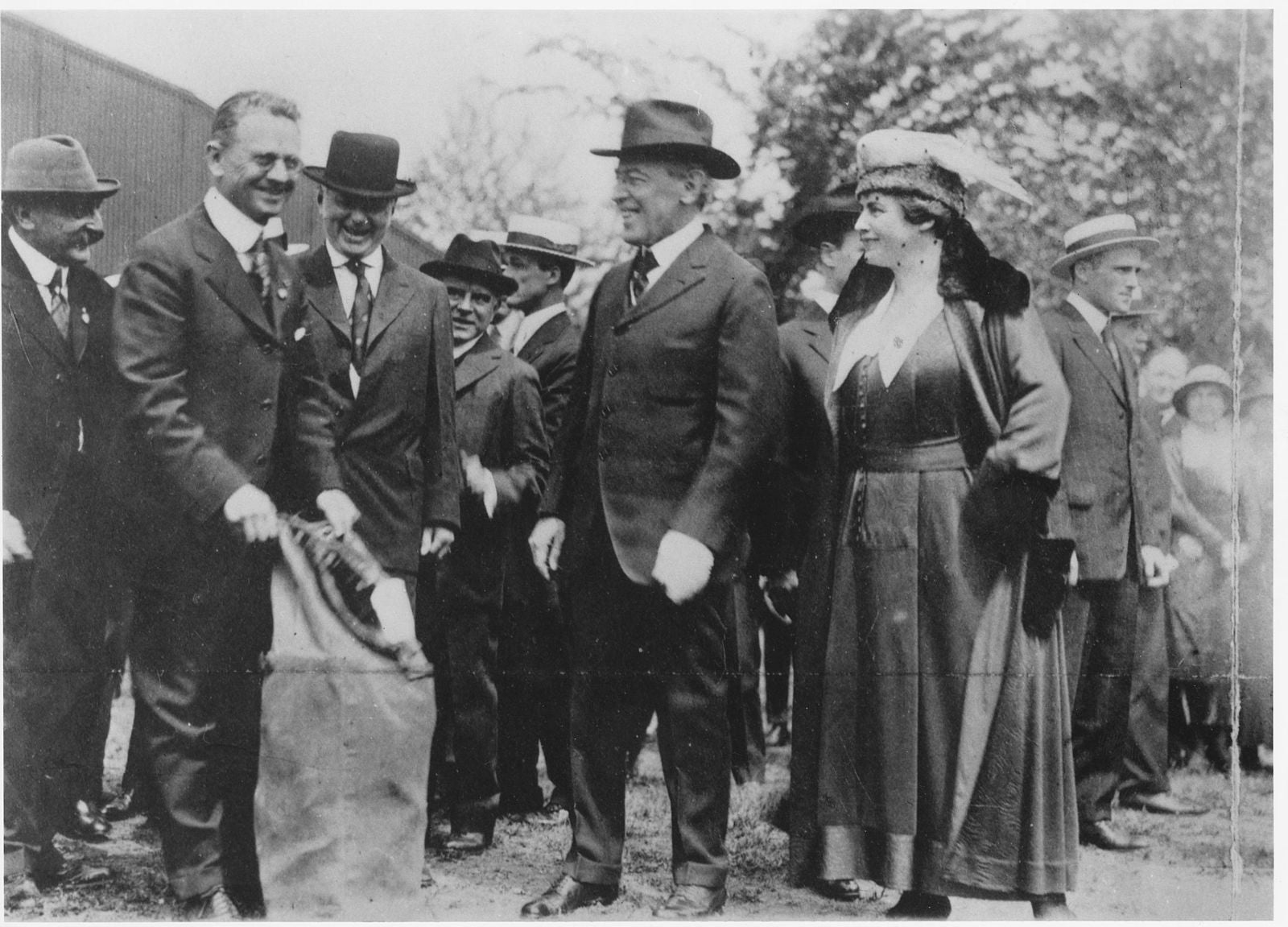

On the morning of May 15th – as Fleet struggled with these questionable aircraft and attempted to get at least one of them back to Washington – a crowd began to gather at Potomac Park to witness the inaugural airmail flight. Lt. George Boyle was eager to prove himself as a pilot. Fresh out of flight school, this honor was unlike anything he had been prepared for. As he looked around the audience, he not only saw his new fiancé and father-in-law but also President Woodrow Wilson and the First Lady.17 The excitement from the audience was building. It was a great day for flying, seventy degrees, and clear skies.18 Boyle was ready to take on this great responsibility. All that was missing was his plane.

It wasn’t until 25 minutes before he was supposed to take off that Major Fleet landed the plane Boyle would be flying in Potomac Park. The audience was excited, and so was the President, who showed great interest in this new technology. To the delight of the crowd, President Wilson added mail to the sack of letters waiting to be delivered. He had written his name across the stamp and was sending the letter to be auctioned off for the benefit of the Red Cross as part of a drive for wartime funds.19

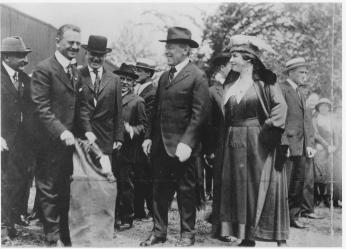

Reuben Fleet and George Boyle preparing for Boyle’s inaugural flight. Fleet had only landed the plane Boyle would be using 25 minutes before the scheduled take-off. (Source: Smithsonian Institution from United States, via Wikimedia Commons)

However, Major Fleet did not show the same enthusiasm. As he met with the young pilot he said, “We haven’t got much time…Here, Boyle, I’ll show you how to get to Philly,” and pulled out a road map to direct the Lieutenant.20 Other forms of aerial direction had not yet been developed, so pilots had to rely on road maps, learning how to follow railroad tracks from city to city.21

After reviewing the maps, discussing other directional questions, and packing the mail, George Boyle was finally ready. He climbed into the cockpit. The mail was loaded into the plane. With the attention of the audience, Boyle went to start the plane. He flicked the switch, the assisting mechanic, Sargent E. F. Waters, spun the propeller, and…nothing.

So, Waters spun the propeller again.

The engine coughed and died.22

Major Fleet couldn’t believe it, he had just flown this very plane all but 25 minutes prior. As he and Waters inspected the plane, it finally clicked: the plane needed fuel.

With some fresh fuel, the plane finally started, to the relief of the audience and the President, who had been overheard saying to the First Lady “We’re losing a lot of time here.”23 But after some nervous moments, George Boyle took off right on schedule. Once airborne, he circled the field and then headed off into the distance.24

While George Boyle’s flight was deemed as the inaugural airmail flight, the pilot flying from New York to Philadelphia, Lieutenant Webb, took off at a similar time to Boyle to make the chain of airmail service more continuous. When each pilot arrived at his destination, he was expected to call the office back in Washington, where Captain Benjamin Lipsner was managing the administrative side of the airmail flights. Each leg was expected to take approximately an hour. Lieutenant Webb had landed in Philadelphia from New York and passed along his mail pouch to Lieutenant Edgerton, who was headed for Washington with the mail from New York and Philadelphia.25 Lipsner began hearing from the pilots as expected… except for one.

Several hours passed and Lipsner had yet to hear from Boyle, the pilot who had the great honor of flying out of Washington. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Culver was waiting to carry Boyle’s delivery from Philadelphia to New York. Lipsner eventually instructed Culver to fly to New York without Washington’s mail – at least the mail from Philadelphia would be delivered to the Big Apple.26 But as it got later and later in the day, Lipsner grew more and more worried about Boyle.27 Where was the young pilot?

Finally, Lipsner received a call from Boyle. But he was not calling from Philadelphia - he was calling from Maryland. Waldorf, Maryland to be exact, a mere 25 miles southwest of Potomac Park in DC. The pilot reported that his compass wasn’t acting correctly, and he had become confused midflight by the railroad tracks leading out of the District.28 Lost and burning fuel, he crash-landed the plane. However, the embarrassment didn’t stop there. The spectacularly unsuccessful flight had ended a short distance away from the home of Otto Praeger, a high-ranking Post Office official.29

Major Fleet was disappointed. While pilots Culver, Webb, and Edgerton had made successful flights, the one that had received Presidential attention had been an utter failure. Perhaps the only saving grace was that with the war continuing overseas, not much media attention was paid to this postal fiasco. Plus, the Post Office Department could easily deem the day a success on account of the other successful flights – especially considering they had another pilot fly Boyle’s mailbags from D.C. to Philadelphia the following day.

After Boyles' failure, Major Fleet requested that another pilot take over the D.C. to Philadelphia route, as he was concerned with the young pilot's flying skills and apparently poor sense of direction. However, the Post Office requested that the Lieutenant get another shot at making the journey. Once again, Major Fleet didn’t really have a say in the matter, and George Boyle prepared for his second flight from Washington on May 17th.30

For the second flight, military officials took extra precautions to ensure the pilot didn’t get lost again and made it to Philadelphia successfully.31 With his plane packed up and ready for his second attempt at piloting the air mail service, George Boyle went up into the air. Only this time he wasn’t alone. Major Fleet himself, flew alongside in an accompanying plane. After about 40 miles of this tandem flight, Major Fleet cut his throttle and asked if the pilot could continue on his own. Boyle yelled out, “I’m okay” so, with a wave, Major Fleet peeled away from Boyle, confident that the young pilot would continue north.32

However, once again, Boyle’s northbound flight turned south. Told to follow the shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay towards Philadelphia, he got turned around and took the instruction a little too literally.33 About three hours after his second take-off, George Boyle found himself landing near Cape Charles, Virginia, about 140 miles south of his starting point and 288 miles south of his destination.34 This was about as far south as he could go before the Bay turned into the Atlantic Ocean.35 Unprepared to make the world’s first transatlantic flight, Boyle refueled by buying gas from a farmer and, once again, headed north towards Philadelphia.

Seven and a half hours after the projected landing time, George Boyle finally made it to Philadelphia.36 But by the time he arrived, it was dark out, he was running out of the fuel he had bought from the farmer, and he couldn’t see where he was supposed to land. So, in true George Boyle fashion, he crash-landed on a country club golf course. In the process, he was thrown out of the cockpit. While his injuries were relatively minor, the plane suffered significant damage.37

Perhaps due to his high-ranking connections, the Post Office suggested giving Boyle a third chance, to make the flight from D.C. to Philadelphia, but Major Fleet had seen enough. He and Secretary Baker refused the Lieutenant’s services and George Boyle’s career as an airmail pilot ended. In fact, it seems he stopped flying altogether.38

The plane on the “Inverted Jenny” stamp was used to commemorate the first airmail flight and shows the serial number of the plane flown by George Boyle. (Source: Bureau of Engraving and Printing, via Wikimedia Commons)

The airmail service would go on without him, however. Boyle was replaced by Lieutenant E. W. Kilgore as the Army continued flying mail for the Post Office until August 1918.39 At that point, the Post Office bought its own planes and hired its own pilots, continuing this service until 1927 when it was taken over by private contractors.40

So, were these early airmail failures Lieutenant Boyle’s fault? Interestingly, Major Fleet didn’t think so – at least not entirely. Fifty years after the fateful flights, Fleet reflected on the bizarre chain of events. He acknowledged that the road maps provided no real value to pilots and, to make matters worse, “the magnetic compass in any airplane was highly inaccurate and was affected by everything metal on the airplane.”41 Additionally, future pilots weren’t all that successful either. In the days following Boyle’s inaugural mistakes, Lieutenant Bonsal crashed his aircraft in New Jersey, while many others had forced landings.42 But while the snakebitten Boyle was let off the hook (sort of), there was a more permanent reminder of airmail’s rocky start.

To honor the first Airmail flight, a postage stamp picturing the Jenny plane was issued on May 10th, 1918 – just a few days before George Boyle took off from Potomac Park. But due to an error in the printing, approximately 100 of the stamps showed the plane upside down, even as the words were right side up. Thanks to the error, the so-called “Inverted Jenny” stamp is now one the most famous and valuable stamps in existence and has sold for upwards of $1.5 million.43 What a perfect way to honor the topsy-turvy first airmail flights.

Footnotes

- 1 Carroll V. Glines, “The Day the Airmail Started,” Air Force Magazine, December 1989, 98.

- 2

“Reuben H. Fleet (1887-1975),” San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story (blog).

- 3 Glines, “The Day the Airmail Started,” 98.

- 4

- 5 Glines, “The Day the Airmail Started,” 99.

- 6

Rueben H. Fleet, Ed Havens, and Otto Praeger, The Father of Airmail Looks Back, interview by Tom Bomar, Radio Station KFSD, May 18, 1938; There is some dispute about who was in charge of the first airmail service. Benjamin B. Lipsner claims he was the first "superintendent" of the airmail service, and while he was heavily involved, Post Office officials and most sources identify Major Fleet as the one responsible for organizing the service with military support. Additional documentation acknowledges Lipsner's leadership as starting in July 1918, two months after the first flight.

- 7 William Wagner, Reuben Fleet : And the Story of Consolidated Aircraft (Fallbrook, CA : Aero Publishers, 1976), 53.

- 8 Glines, 99; after modifications, the plane was redesignated as JN-4HM. See Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives” for more information on the plane's classifications before and after modification.

- 9

Jordan Golson, “The Humble WWI Biplane That Helped Launch Commercial Flight,” Wired.

- 10 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

- 11 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

- 12 “The 1918 Flights;” Only four pilots were needed for a day’s worth of deliveries to cover distances from D.C. to Philadelphia, Philadelphia to New York, and vice versa. Culver, Webb, Edgerton, and Boyle all made flights on the first day. Bonsal and Miller made flights the following day and throughout the Army’s airmail service.

- 13 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

- 14

- 15 Wagner, “Reuben Fleet: The Story of Consolidated Aircraft, 54.

- 16 Glines, “The Day the Airmail Started,” 100.

- 17 Rueben H. Fleet, Ed Havens, and Otto Praeger, The Father of Airmail Looks Back.

- 18 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

- 19 Glines, 100.

- 20 Glines, 100.

- 21 Rueben H. Fleet, Ed Havens, and Otto Praeger, The Father of Airmail Looks Back.

- 22 Glines, 100.

- 23 Glines, 100.

- 24 Tim Brady, “The Aircraft Accident Investigation That Never Was,” Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research 23 (Winter 2014), 5.

- 25 Glines, “The Day the Airmail Started,” 101.

- 26 Glines, 101.

- 27 Glines, 100.

- 28 George Boyle, G.L. 2nd Lt. U.S. Army. Pilot’s Daily Report, May 15, 1918. Rg. No. 28, E. 157B, 4.05, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D. C.

- 29 “Lieut. Miller Off With Aero Mail,” The Evening Star, May 18, 1918.

- 30 Glines, “The Day the Airmail Started,” 100.

- 31 “Air Mail Departs on Schedule Time,” The Evening Star, May 17, 1918.

- 32 Wagner, “Reuben Fleet: The Story of Consolidated Aircraft, 56.

- 33 “Wrong Way Boyle.”

- 34 “Lieut. Miller Off With Aero Mail.”

- 35 “Wrong Way Boyle.”

- 36 “Lieut. Miller Off With Aero Mail.”

- 37 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

- 38 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

- 39 Wagner, “Reuben Fleet: The Story of Consolidated Aircraft, 56.

- 40 Glines, 101.

- 41 Glines, 101.

- 42

- 43 Swopes, “George Leroy Boyle Archives.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)