What's in a Name? Anacostia

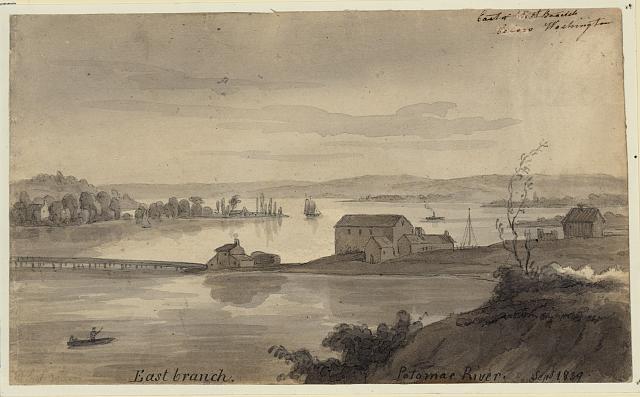

How did the historic D.C. neighborhood of Anacostia get its name? The short answer is, of course, its proximity to the Anacostia River; but the river has its own history that’s worth unpacking. Like the Potomac, Anacostia’s name can be traced back to the area’s Indigenous population – in this case, the Nacotchtank of the Algonquian stock.

Sadly, much of Nacotchtank history has sadly been neglected in favor of more powerful neighboring Native peoples, but their story is of great significance to local history. Their land comprised the main settlement of American-Indians within and adjoining what’s now D.C., and their tribe boasted 300 members and at least 80 trained warriors.[1] Like the Patawomeke people, the Nacotchtank spoke the language of the larger Powhatan Confederacy but were very much their own tribe.[1] By the time English colonizers made their way to the region in the early 1600s, the Nacotchtank Indians had been living along the river for an estimated 10,000 years.[2]

Most of what we know of the meaning of “Nacotchtank” and how it etymologically evolved into “Anacostia” comes from the journals and records of white colonizers, as there is sadly little in the way of surviving records that can be traced directly to the Nacotchtank people themselves.

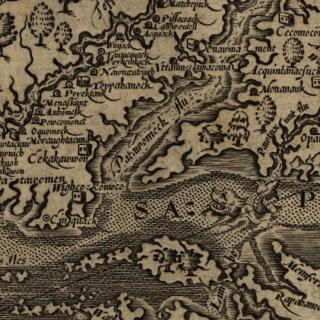

John Smith was the first European colonizer to mention the Nacotchtank, recalling his voyage across the Chesapeake in June 1608. “At Moyaones,” wrote Smith, “the Nacotchtant, and Toags the people did their best to content us.”[1] “Nacotchtank” also appears on a map published by Smith in 1612.[1] The next time we see mention of the tribe is in 1622, when white colonizers partnered with a neighboring American-Indian tribe to attack the Nacotchtank and drive them from their cabins on what is now the Navy Yard bridge.[1] In an unjust yet common turn of events, English colonizers stole more and more of Nacotchtank land and, as the Records of the Columbia Historical Society noted in 1920, “the Indian settlement Nacotchtank became the white settlement Anacostia.”[3]

The general consensus is that “Nacotchtank” is a spelling of the Indian word “Anaquash(e)tan(i)k,”[3] which referred to a “town of traders”[3] or “village trading center.”[2] (As a side note: It was a pretty apt moniker, since the tribe was well known for its trade; they even traded fur with the Iroquois tribe all the way up in New York.[4]) “Anaquash(e)tan(i)k,” was later Latinized by Jesuits and by Lord Baltimore into “Anacostan,” and we see the term “Anacostan” in reports by white colonizers as early as the 1630s.[1] Since most of the Nacotchtank people settled along the river, white settlers began to refer to the river as the “Anacostia” river.

Though the Latinized-name has endured, the Nacotchtank tribe’s physical presence in the area unfortunately hasn’t. Pinched by the encroachment of European settlers, the tribe relocated to what became known as Anacostine Island (now Theodore Roosevelt Island) in the 1660s.[4] In the 1700s, the shrinking number of Indigenous peoples in the area motivated the surviving members of the tribe to merge with the Piscataway people and other northern tribes.[4]

According to officials of the National Museum of the American Indian, there are no known Nacotchtank people living today.[4] There is one D.C. resident, though, who’s been working to ensure memory of the Anacostan Indians endures. Armand Lione researches Anacostan history on his blog. As Lione told The Washington Post recently, "We had American Indians right here in D.C. that were living on these well-known modern-day spots like the White House and Capitol Hill. People should know this, recognize them and remember."[4]

Footnotes

- a, b, c, d, e, f Otis T. Mason, W J McGee, Thomas Wilson, S. V. Proudfit, W. H. Holmes, Elmer R. Reynolds and James Mooney. “The Aborigines of the District of Columbia and the Lower Potomac - A Symposium, under the Direction of the Vice President of Section D.” American Anthropologist, Jul., 1889, Vol. 2, No. 3 (Jul., 1889), pp. 225-268

- a, b Megan Buerger. “The history of the Anacostia River,” Washington Post, 2 May 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/the-history-of-the-anacostia-river…

- a, b, c Charles R. Burr. “A Brief History of Anacostia, Its Name, Origin, and Progress.” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington D.C., Vol 23 (1920), pp. 167-179.

- a, b, c, d, e Dana Hedgpeth, “A Native American Tribe Once Called D.C. Home,” Washington Post, 22 November 2018.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)