“A Lady of Practical Benevolence”: Dorothea Dix and the Creation of St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C.

In 1836, Dorothea Dix was sick. Very sick. For the past several years of her life, her attempts at educating the poor children of Massachusetts had been interrupted by ever-worsening “asthma, insomnia, dyspepsia, incapacitating headaches, spasms of the heart, rheumatism, and partial paralysis of her right side.”1 At only 34 years old, she seemed on the brink of death. Her friends insisted she risk the North Atlantic crossing and try to recover in England. The change of air would do her good.

Dix reluctantly obeyed the urging of those around her, committing herself to the care of the Rathbone family at Greenbank, their estate near Liverpool. The new scenery did in fact provide her some relief, and it was just as much mental as physical. The serious symptoms which had plagued the single daughter of an overzealous Methodist minister for so long had also brought intense bouts of depression in which Dix questioned her purpose and considered her sin - obviously, she thought, the root of her illness.

Eventually though, even the worst of the depression began to fade and Dix was able to engage with her hosts on the important topics of the day. Ever an advocate for the less fortunate, Dix was intrigued to find the Rathbone family involved in philanthropy and legislation to improve conditions for those who, like Dix, suffered from mental illness.

When she got back to the States, Dix decided to find out more.

Starting with Massachusetts and working her way further afield, Dix began to visit the jails, almshouses, and private homes which housed what she termed the “indigent insane.”2 She was shocked by what she saw.

“[I]n jails, in poor-houses, and in private dwellings, there have been hundreds, nay, rather thousands, bound with galling chains, bowed beneath fetters and heavy iron balls, attached to drag-chains, lacerated with ropes, scourged with rods, and terrified beneath storms of profane execrations and cruel blows; now subject to gibes, and scorn, and torturing tricks-now abandoned to the most loathsome necessities, or subject to the vilest and most outrageous violations.”3

This would not stand. Dix immediately began petitioning state legislatures for land, funds, and laws to protect “that class of people who, of all others, are most entitled to our sympathy and care.”4 She met with quick success, and within ten years had traveled 60,000 miles around the country and visited every state with the limited exceptions of North Carolina, Florida, and Texas. But it wasn’t enough. Her conservative estimate put the number of “insane” people in the United States at over 22,000 and her state-by-state approach only reached a few dozen to a few hundred at a time.5 She had to go bigger.

By the time 45 year old Dorothea Dix moved to Washington, D.C. in 1847-48, people knew who she was. Senator Pearce of Maryland described her as “a lady of well known practical benevolence” and she was soon in regular correspondence with then Vice President Millard Fillmore.6 Dix got straight to work on a “memorial” to Congress detailing her proposal for a bill which would grant five million acres of federal land to the states in order for them to care for their mentally ill citizens. She spared no detail of what she had seen in her travels.

“In A., insane man in a small damp room in the jail; greatly excited; had been confined many years; during his paroxysms, which were aggravated by every manner of neglect, except want of food, he had torn out his eye, lacerated his face, chest, and arms, seriously injured his limbs, and was in a state most shocking to behold.”7

“In P., nine very insane men and woman in the poor-house, all exposed to neglect and every species of injudicious treatment; several chained, some in pens or stalls in the barn, and treated less kindly than the brute beasts in their vicinity.”8

She even called out Washington, D.C. specifically for the “black, horrible histories” of the jails and almshouses which housed the insane of the city.9

It can be difficult to get things done in Washington, and “Miss Dix’s Bill,” as it was called, was no exception.10 While she waited the years that it would take for Congress to wrestle through all the implications of her proposal, she got to work on another project.

In addition to the jails and almshouses, mentally ill residents of Washington were currently being shipped up to Mount Hope Retreat in Baltimore, Maryland to be cared for, as the federal city had no facilities for them at home. It was the solution Congress had come up with in the 1830s when the Committee on the District of Columbia had asked for funds to establish their own hospital.11 It would be cheaper, the government decided, to pay Maryland to take care of the city’s poor mentally ill and the veterans who were trying to claim psychiatric care in return for their service.

Like everywhere else though, the hospitals in Baltimore were filling up. A citizen of that city wrote to a D.C. physician, urging the capital to build their own hospital: “I beg leave to call the attention of the citizens of the District of Columbia to the rapid increase of insanity in their community, and to the necessity of acting promptly on this all-important subject.” The managers of Mount Hope had made the decision to “exclude for the future all such patients coming from the District of Columbia” and had given notice to “the Marshal to remove those now under care on or before the 1st of January, 1853.”12

It was time for D.C. to build a hospital. Fortunately for them, the perfect woman for the job was currently staying with the superintendent of the Smithsonian and couldn’t wait to get her hands on a new project.

Within six months of that impassioned plea from a Baltimore resident, Dr. C. H. Nichols, appointed the first superintendent of the new institution at Dix’s recommendation, was advertising for proposals from local businesses for bricks, building stones, barrels of lime, barrels of hydraulic cement, brown sandstone, and the human labor to put it all together into what would become the Government Hospital for the Insane.13

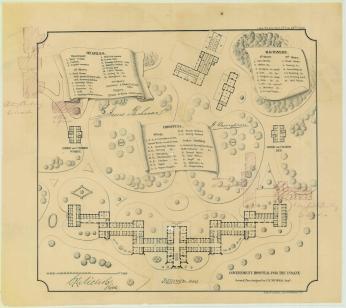

The physical space of the hospital was just as important to Dix’s plans as any other part of its construction. She advocated for a new system of psychiatric care called “moral management,” in which patients were fed well, participated in therapies, had access to nature, and were generally treated as human beings - a new concept at the time. Thomas Kirkbride, another member of the psychiatric activism network in which Dix labored, had come up with an architectural design which would contribute to the new humane treatment methods. It included several wings situated so that no patient looked into any other patient’s room and gave each individual open access to fresh air and a peaceful atmosphere. His was the design upon which the new Government Hospital would be modeled.14

The site for the hospital was equally crucial. The newly founded Association of Medical Superintendents of American Institutions for the Insane provided four primary principles which dictated how the spot should be chosen. The Secretary of the Interior cited them in a report to Congress:

1st. That every hospital for the insane should be in the country, not within two miles of a large town, and accessible at all seasons.

2d. That no public institution should possess less than one hundred acres of land.

3rd. That there should be an abundant supply of water convenient to the asylum.

4th. That a location should be selected which would admit of underground drainage, convenient pleasure-grounds, and an agreeable prospect.15

President Fillmore personally toured several sites with Secretary Stuart, but Dix made the final recommendation. She wanted the 185 acre farm belonging to Thomas Blagden and his wife, located “about a mile east of the Navy Yard…on a high ridge with fine views of Washington, Georgetown, Alexandria,” and the surrounding countryside, and with “expansive frontage along the east bank of the Anacostia.”16 The land wasn’t for sale, but that didn’t bother Dix. She sent Dr. Nichols in to negotiate.

Blagden loved the land and was reluctant to part with it - and certainly not for the $25,000 Congress had appropriated for the purchase. The plot was worth at least $40,000. He rebuffed Nichols at every turn, until the doctor went back to Dix in “thoroughly depressed spirits.” Dix, though, was unperturbed. “We must try what can be done,” she told Nichols, and went to speak to Blagden herself. She implored the man to make the land available to the hospital, that it might serve “the future good of thousands of his suffering fellow-creatures” rather than just his own family. Dix’s “appeal proved irresistible” and Blagden agreed to sell the property and even accepted the price proposed by Congress.17

By the time the hospital was ready to receive its first patients (several months before the facility would be completed), the situation was getting desperate. The hospital would have the capacity to house 85 patients and there was already a waiting list of 84, made up of “twenty insane persons, belonging to the army and navy establishments, and fifty-three indigent insane in the Baltimore institutions, supported by the Government, and eleven are detained in jail in this city.”18

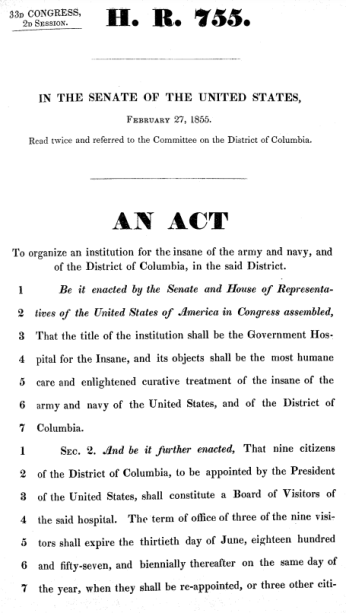

Congress passed the official bill sanctioning the hospital in 1855, a month after the first patient was admitted: “[I]ts objects shall be the most humane care and enlightened curative treatment of the insane of the army and navy of the United States, and of the District of Columbia.”19 And so it was.

Today, we call the Government Hospital for the Insane by another name: St. Elizabeths Hospital. Wounded Civil War soldiers introduced the new moniker when they preferred to call their temporary home after the original colonial name for the land rather than admit to family members that they were languishing in an insane asylum. Congress made the change official in 1916. In 1987, the federal government turned over control of the hospital to the D.C. Department of Mental Health and in 2010, it moved from its original location to a new facility on Alabama Avenue.20

In 1854, the year before St. Elizabeths opened, Congress passed Miss Dix’s Bill. Her elation was short-lived, however. President Franklin Pierce quickly sent back a veto, claiming that the Constitution did not grant Congress the authority to distribute the land for that purpose.21 A frustrating outcome, to be sure, but Dorothea Dix’s secondary Washington project would go on to help thousands of people and continue to be, as she had hoped, “a model institution of its kind.”22

Thanks, Miss Dix.

Footnotes

- 1

David Gollaher, Voice for the Mad : The Life of Dorothea Dix (New York : Free Press, 1995), 36.

- 2

D. L. Dix, “Memorial Of Miss D. L. Dix To the Senate And House Of Representatives Of The United States,” Disability History Museum, June 23, 1848, 19.

- 3

Dix, “Memorial,” 5.

- 4

“In Senate: Petition for the Relief of the Insane,”Daily National Intelligencer, June 26, 1850.

- 5

Dix, “Memorial,” 4.

- 6

“In Senate: Petition for the Relief of the Insane.”

- 7

Dix, “Memorial,” 5.

- 8

Dix, “Memorial,” 5.

- 9

Dix, “Memorial,” 15.

- 10

Gollaher, Voice for the Mad, 319.

- 11

“Institutional Memory,” National Archives, August 15, 2016.

- 12

“The Insane at Baltimore,”Daily National Intelligencer, August 4, 1852.

- 13

C. H. Nichols, “Advertisement,”Daily National Intelligencer, January 25, 1853.

- 14

Thomas Otto, “St. Elizabeth’s Hospital: A History” (U.S. General Services Administration, May 2013), 14–15.

- 15

Alex H. H. Stuart, “Report of the Secretary of the Interior, Communicating in Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate, Information as to the Steps Taken to Establish a Lunatic Asylum in the District of Columbia” (Washington, DC, 28 December 1852), 2.

- 16

Otto, “St. Elizabeth’s Hospital: A History,” 11.

- 17

Francis Tiffany, Life of Dorothea Lynde Dix (Boston, Houghton, Mifflin Company, 1890), 154.

- 18

“Local and Personal,” Washington Sentinel, December 9, 1854.

- 19

“An Act To Organize an Institution for the Insane of the Army and Navy, and of the District of Columbia, in the Said District.” (congress.gov, February 27, 1855), 1855-02-27.

- 20

“Historic Medical Sites Near Washington DC,” Product, Program, and Project Descriptions, National Library of Medicine (U.S. National Library of Medicine, August 8, 2022).

- 21

Franklin Pierce, “Veto Message” (The American Presidency Project, May 3, 1854).

- 22

“Local and Personal.”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)