The Giant D.C. Mosquito Net That Could've Cured Malaria

There’s a common saying (and belief) that Washington, D.C. was built on a swamp. While that’s not actually the case, it is true that the District’s rivers and tributaries—and the surrounding marshland—have caused some problems in the past. In the nineteenth century, the low-lying area around the National Mall and Tidal Basin was the perfect breeding ground for one of the largest public health concerns at the time: mosquitoes.

The insects are a residual annoyance today, but they could be extremely dangerous for previous generations of Washingtonians. Mosquitoes are the carriers of malaria, a dangerous parasitic disease transmitted to humans through bites. While known as a tropical disease today, malaria spread throughout the American colonies during the early decades of colonization, showing up in all colonies and territories by the 1750s.1 By the nineteenth century, outbreaks were common and even expected in the summer months—especially in low, wet, and hot areas like Washington, where the mosquito carriers thrived.

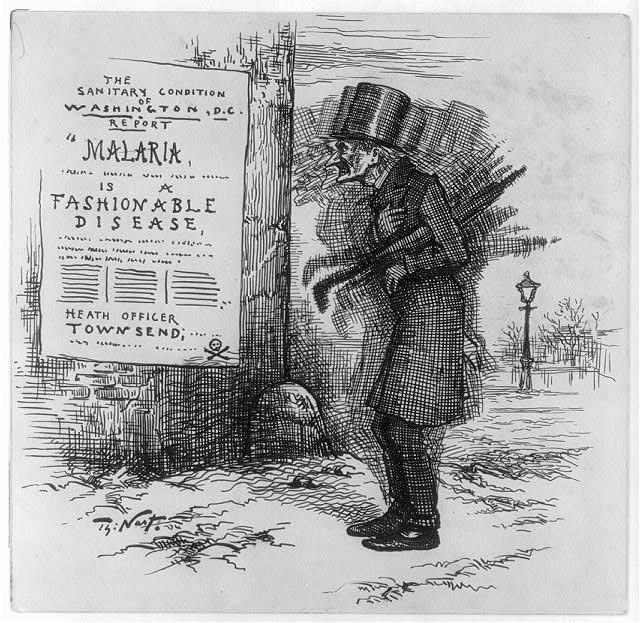

There was just one problem: no one actually knew that mosquitoes were the cause of the disease. Until the 1890s, the majority of scientists and doctors believed that the disease was viral and carried through “miasma,” or bad air—the name “malaria” literally means “bad air” in Italian.2 In the summer, when the weather was heavy and humid, Washingtonians were convinced that the disease was carried through the air from person to person, leaving no one safe. And without the appropriate knowledge to combat the disease, there was very little that doctors could do once their patients were diagnosed.

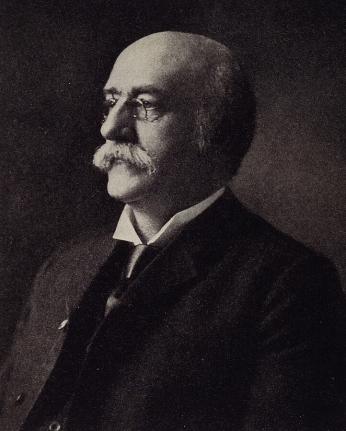

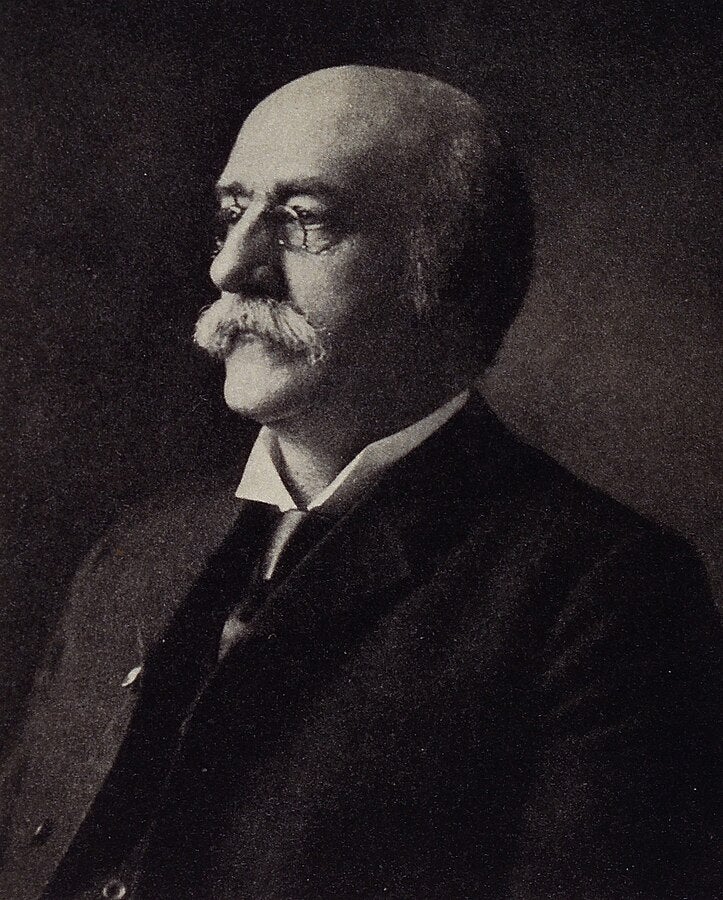

But there was one man in Washington who thought he had a chance to save everyone. Meet Dr. Albert Freeman Africanus King—a Civil War doctor, medical professor, witness to history, and an early believer in the idea that mosquitoes caused the seasonal malaria outbreaks.

King was born in England in 1841, but his family emigrated to Virginia when he was a teenager. He trained as a doctor at the National Medical College (now George Washington University Medical School) before receiving his M.D. at the University of Pennsylvania.3 During the Civil War, King treated injured soldiers on both sides of the conflict, eventually becoming a Union surgeon at the Lincoln Hospital in Washington. After the war, he taught medicine at his Washington alma mater and lectured on topics in toxicology and obstetrics.4 He was also a consulting physician at area hospitals, a member of influential medical societies in the District, the author of textbooks, and a resident of Massachusetts Avenue NW.5

He is perhaps best known to history (and Google) through a fateful coincidence. On April 14, 1865, King attended a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre—making him one of the witnesses of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. King was one of the doctors who rushed to the President’s side, assisting in efforts to assess Lincoln’s injuries and resuscitate him.6 He accompanied Lincoln across the street to the Petersen House and stayed with him all night, probably witnessing his death the next morning.7

But King’s greatest legacy should be his theories on the prevention of malaria, a disease that became even more dangerous and widespread in the late nineteenth century. During an outbreak in May 1881, First Lady Lucretia Garfield contracted the disease, which attracted national attention. A correspondent for a Cincinnati newspaper reported that the illness was not a surprise, since the White House was “situated just where the river malaria can have full sway over its inmates.”8 The First Lady recovered, but the country was now aware of just how susceptible Washingtonians were to the disease.

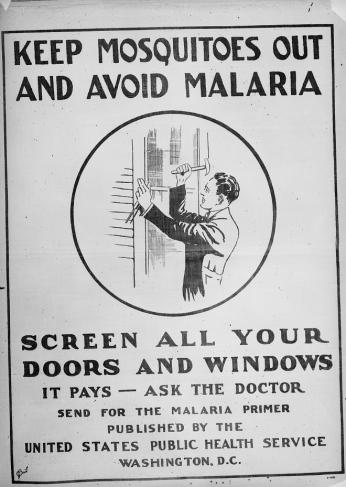

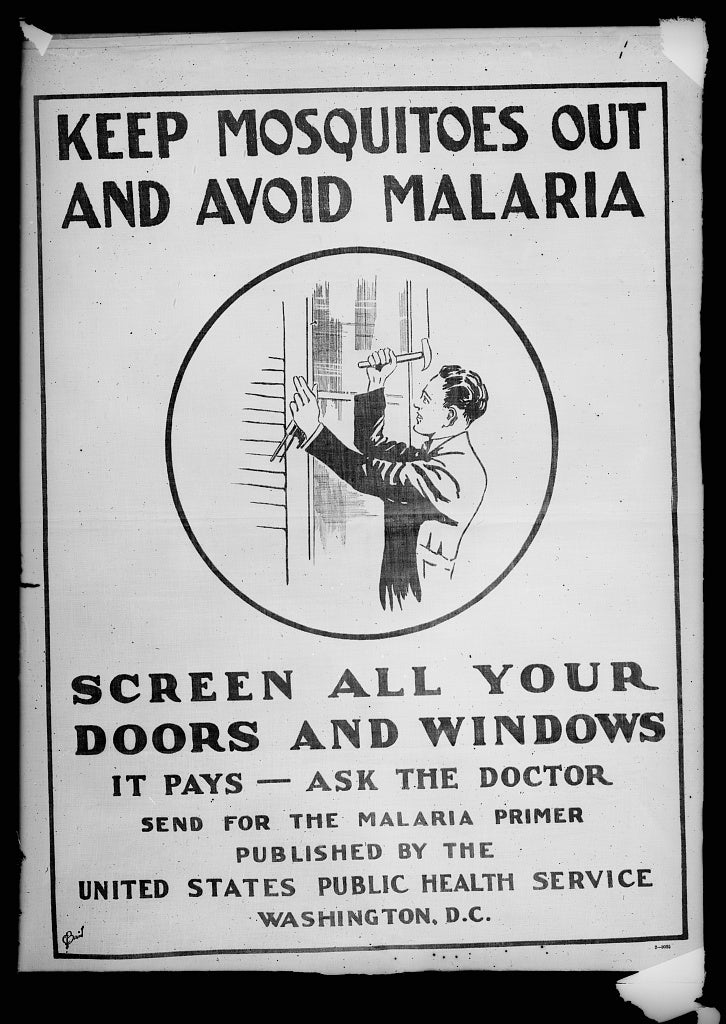

The following year, on February 10, King was invited to speak before the Philosophical Society of Washington. He decided to share his latest research on a topic that, he believed, would improve the lives of the people in his city: he read a paper that posited that mosquito bites, not bad air, carried malaria between humans. It wasn’t an entirely new theory but King was potentially the first to fully outline and present the reasoning behind the argument.9 And his reasoning was sound—the habits of mosquitos was the only common thread that could connect all of the known facts about malaria (the effects on people living in low and wet areas, its spread during hot weather, contraction being most common after dark, the lack of discrimination between age groups, and more).10 He even suggested an easy remedy for the issue, one that is still in use today: use netting to prevent mosquitoes from affecting an area. However, when it came to trapping mosquitoes on a larger scale, his plan may have been a bit too out-there to be taken seriously:

“With relation to the city of Washington, it was suggested that the Washington monument would afford a good opportunity (by placing illuminated fly-traps at different elevations on its exterior) for ascertaining the height at which mosquitoes fly, or are brought by the wind from the adjacent Potomac flats.”11

In other words, King wanted to install a large wire net on top of the Washington Monument, complete with electric lights to lure the insects to his trap. You can see the method behind the madness, but it’s also easy to understand why this sensational portion of King’s lecture gained the most attention. Many readers thought that the idea (and, therefore, the rest of King’s theory) was a joke or prank.12 So King’s mosquito theory, despite gaining attention, was ignored by his colleagues. The paper itself was only ever published as summaries in popular journals like Popular Science Monthly (which carried an abridged version in 1883).13

We now know that King’s theory was absolutely true, even if his methods for prevention were unconventional. Infuriatingly, it took the rest of the world two decades to catch up with him. In 1898, Ronald Ross, a British doctor, announced that he had discovered the parasite that causes malaria—and he found it in the stomachs of mosquitoes. Ross was heralded as a medical hero and awarded a Nobel Prize in 1902. While Ross’s work was remarkable and transformative, it’s maddening to think that such research could have begun decades earlier here in Washington, if only King’s theories had been believed by his colleagues.

King wasn’t recognized for his research during his life but has been posthumously lauded for his theory and suggestions. When he died in 1914, several Washington newspapers carried his obituary and noted him as one of the first to solve “the malaria problem.”14 Modern scientists have granted him a well-deserved place within the history of malaria research. And King would probably be pleased to know that modern treatments and prevention measures eliminated malaria (except for occasional cases) in the 1950s.

For a moment, though, let’s pretend that King’s original proposition hadn’t been ignored. It would have been really fun to write an article about the construction and installation of a giant net atop (at that time) the tallest structure in the world, all in the name of public health.

Footnotes

- 1

Andrea Prinzi and Rodney Rohde, “The History of Malaria in the United States,” American Society for Microbiology (15 September 2023), https://asm.org/articles/2023/september/the-history-of-malaria-in-the-united-states

- 2

Ibid.

- 3

“Albert King,” Nature (18 January 1941), https://www.nature.com/articles/147085d0

- 4

Edward L. Lach, Jr., “Albert Freeman Africanus King,” American National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2005), 318.

- 5

“Heart Disease Fatal to Dr. Albert F.A. King,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) 15 December 1914, p. 17 col. 2.

- 6

Michael Mahr, “The Lincoln Assassination: Murder and Medicine,” National Museum of Civil War Medicine (11 April 2023), https://www.civilwarmed.org/lincoln-assassination-murder-and-medicine/

- 7

“Frequently Asked Questions: the Petersen House,” National Park Service (27 October 2024), https://www.nps.gov/foth/learn/historyculture/faq-petersen-house.htm

- 8

“Malaria: The Evil Spirit of the White House,” National Park Service (27 May 2021), https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/malaria-the-evil-spirit-of-the-white-house-the-first-lady-s-illness-part-two.htm

- 9

Lach, American National Biography, 318.

- 10

A.F.A. King, “The Prevention of Malarial Diseases, Illustrating Inter Alia, The Conservative Function of Ague,” The National Medical Review 8 (1899), 400-403.

- 11

Ibid.

- 12

Leon J. Warshaw, Malaria: The Biography of a Killer (Rinehart & Company, 1949), 63-64.

- 13

Lach, American National Biography, 318.

- 14

“Heart Disease Fatal to Dr. Albert F.A. King,” The Evening Star (Washington, D.C.) 15 December 1914, p. 17 col. 2.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)