The U.S. Capitol's Civil War Residents

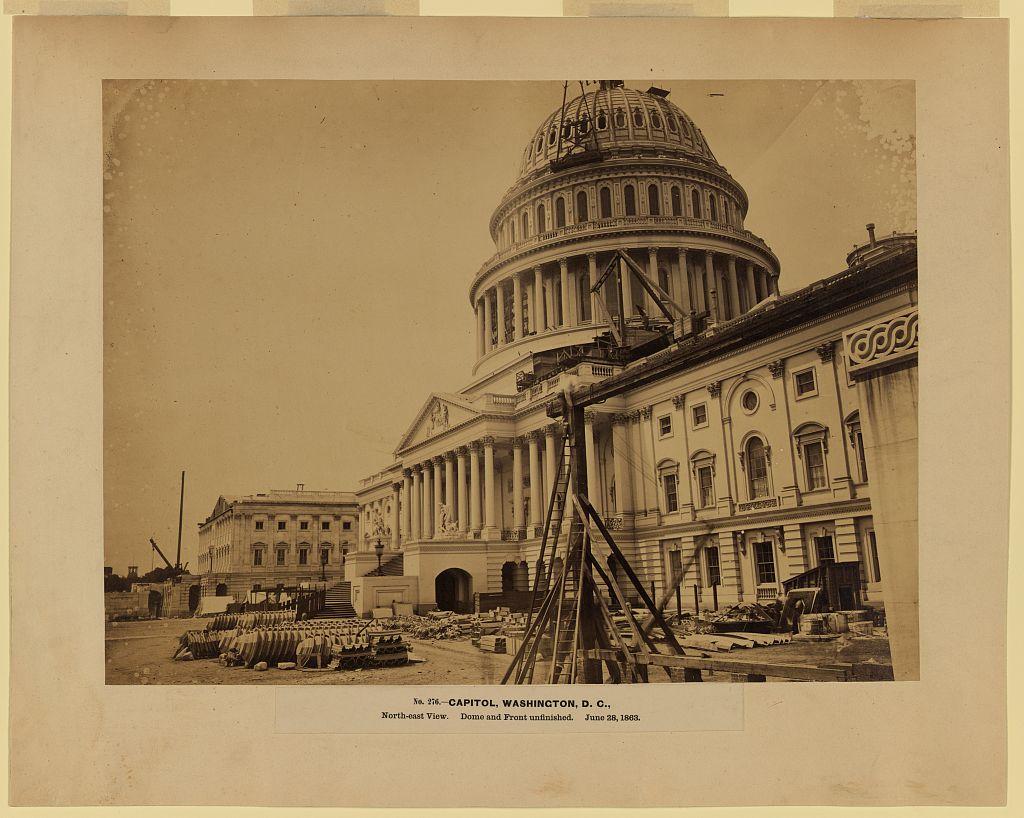

The first shots of the Civil War rang out at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Three days later, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to “suppress the rebellion,” and he recalled Congress for a special session beginning July 4.[1] (Congress had adjourned in March,[2] and work which was underway to build an expansion to the U.S. Capitol Building screeched to a halt.[3])

On April 18, the soldiers began to arrive in Washington, D.C. The first arrivals were a group of volunteers from Pennsylvania, and they were housed in the House of Representatives wing of the currently empty Capitol Building. The next day, the Sixth Regiment from Massachusetts made it to D.C.[4]

“The Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts, nine hundred strong, under the command of Col. Jones, were attacked in Baltimore on their way to Washington,” Senate doorkeeper Isaac Bassett said. “… On arriving here these were marched into the Capitol and immediately occupied the Senate Chamber. . . . The col. made the Vice President’s Room his headquarters. They looked tired I saw blood running down their faces. Their clothes were full of dust. Everything was done that could be for their comfort.”[5]

Clara Barton was working as a clerk at the U.S. Patent Office, about six blocks away from the Capitol. When she heard that wounded troops had arrived, she rushed to the Capitol to tend to them. This marked the unofficial beginning of her work as a Civil War nurse.[6]

By April 20, there were about 30,000 troops staying in the makeshift barracks in the Capitol. Mechanics who had been working in and around the Capitol formed Company E of the National Guard and took up residence in the Revolutionary Claims Committee Room.[7]

“Our life in the Capitol was most dramatic and sensational,” wrote Theodore Winthrop, a member of the Seventh New York Regiment. “We joked, we shouted, we sang, we mounted the Speaker’s desk and made speeches.”[8]

Some of the soldiers also took advantage of the franking privilege, using Senate stationery and envelopes to send letters home.[9]

Architect of the Capitol Thomas U. Walter, who was hired to oversee the expansion project,[10] wasn’t too pleased with the guests’ behavior.

“There are 4000 [troops] in the Capitol with all their provision, ammunition and baggage, and the smell is awful,” Walter wrote in May. “The building is like one grand water closet— every hole and corner is defiled . . . . The stench is so terrible I have refused to take my office into the building. It is sad to see the defacement of the building every where.”[11]

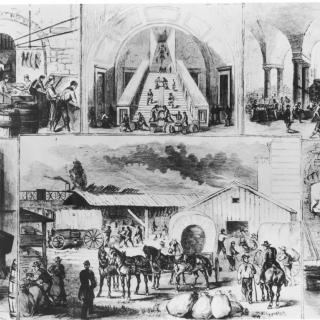

Not only had the soldiers “defiled” the parts of the building where they were living, but the basement of the Capitol had also been turned into a bakery to feed them. Upon their return in July, members of Congress were greeted with the smell of freshly baked bread from the ovens under the great steps of the west terrace.[12] Not everyone was pleased with the aroma. Some worried that the smoke from the ovens could damage important areas of the building,[13] including the books in the Library of Congress.[14]

“The treasure entrusted to my care … [is] receiving great damage from the smoke and soot that penetrated everywhere through the part of the Capitol which is under my charge without any means at my command to prevent it,”[15] Librarian of Congress John G. Stephenson told Public Buildings Commissioner Benjamin French.

Despite the complaints, the bakery stayed. For the time being.

While Congress was in session, the soldiers left their temporary barracks and joined the troops living in other parts of the city. “During the entire war Washington was a military camp,” Ohio Senator John Sherman wrote in his memoirs.[16]

After Congress adjourned in July 1862,[17] the Capitol once again became a temporary home for about 1,000 soldiers.

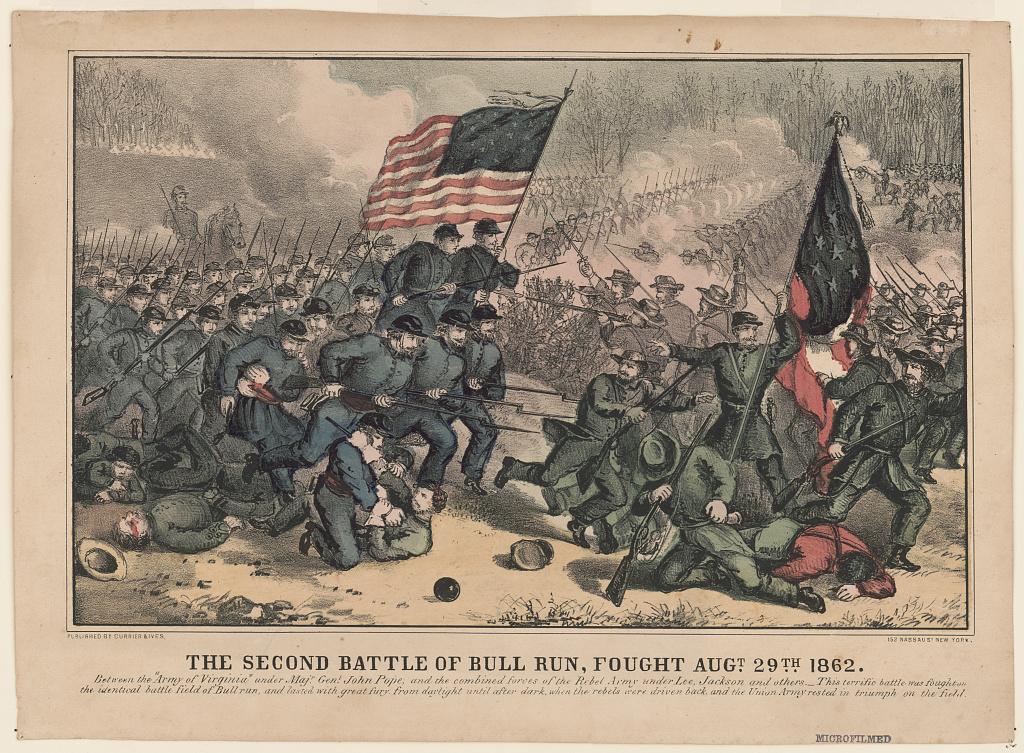

Following the Second Battle of Bull Run in late August 1862, where thousands of soldiers were wounded,[18] “the Headquarters of the Military District of Washington issued Special Order 177, requisitioning the Capitol for use as a hospital.”[19]

On Sept. 2, The National Republican wrote, “The Capitol is now being fitted up for the purpose of using it as a hospital.”[20] The next week, The Evening Star reported that the Capitol hospital would be able to accommodate 1,000 patients. Six blocks away, Barton’s Patent Office was preparing to become a hospital for another 800 patients.[21] She was now on the front lines, tending to wounded soldiers.[22]

By this time, Walter seemed to have forgotten the troops’ previous damage, writing:

“The excitement here is very great and the presence of so many wounded greatly affect the sensibilities of all who have any feeling—poor fellows, what they must suffer. … They have taken the Capitol as a hospital, and the beds are now up in the rotunda, the old Hall of Rep’s, and the passages—one thousand beds have been put up. It does not interfere with our work in the least, and I think the move is a good one.”[23]

Summers in Washington these days can be unpleasant enough, but a building with 1,000 wounded soldiers and no air conditioning made for some less than ideal conditions. All the while, the construction on the Capitol expansion project was still unfinished.[24]

A month later, conditions inside the building had deteriorated considerably.

“I am now writing in the middle of the street, with clouds of dust flying around me,” Walter wrote on Oct. 3. By this point, he had been “compelled to move by the filth and stench, and live stock in the Capitol—there are more than 1,000 sick and wounded in the building and it has become intolerable especially in the upper rooms.”[25]

French echoed Walter’s descriptions.

“In his annual report, French described the deplorable conditions at the Capitol while it was being used as a hospital, and he requested additional funding to pay for the thorough cleaning of the building and to restore the ‘wreck of rooms’ before Congress reassembled.”[26]

By October 1862, the soldiers left the Capitol,[27] the bakery was removed,[28] and construction on the Capitol expansion project resumed[29] in preparation for Congress to meet in December.[30]

Well, all but one soldier left, apparently…

In 1898, the Philadelphia Press wrote, “One of the most curious and alarming of the audible phenomena observable in the Capitol, so all the watchmen say, is a ghostly footstep that seems to follow anybody who crosses Statuary Hall at night.”[31]

The House of Representatives moved out of what is now Statuary Hall in 1857, so the space was used to house some of the wounded soldiers. One of the reasons the House moved was because “the smooth, curved ceiling promoted annoying echoes, making it difficult to conduct business.”[32]

On July 8, 1906, The Washington Post reported the story of a Capitol watchman who said he saw a ghost in Statuary Hall.

“I had been to a part of the building where my duty takes me, and was returning to the western entrance. Just outside Statuary Hall there is an iron staircase, and this I turned to descend. A flash of lighting through a window looking upon the stair lighted up the latter for a second, and in that brief time I caught a glimpse of a figure descending in front of me. I thought it must be one of the other watchmen. The view I caught of the person was not distinct, for whoever it was was at the bottom of the steps while I was at the top. The person kept on ahead of me, though what struck me as peculiar was that I could hear no sound of footsteps. The figure kept on ahead of me at about the same distance as when I first saw it, even though I walked considerably faster in order to come up to it. It descended a certain staircase, and when it reached the bottom and I should say — for, owing to the intense darkness just there I could not see it — there was the loud report of a pistol, and, as I fancied, a cry or groan. I went down, expecting to come upon the scene of a tragedy of some sort, but there were no traces of anything of the sort, and no view of anybody at all.”[33]

In the 1970s, a Capitol staffer reported hearing moaning in Statuary Hall. While trying to find the source of the sound, the staffer said they thought they saw a man in a navy blue military uniform walk across the room before disappearing.[34]

To this day, Capitol staffers still occasionally report seeing the soldier’s shadow drifting around the statues in Statuary Hall.[35]

Are the noises the staffers are hearing the ghost screaming or just some tricky echoes in a two-century-old building? Next time you visit Statuary Hall, keep your eyes and ears open and let us know if you encounter the ghost or any of the other alleged supernatural occupants of the Capitol.

Footnotes

- ^ “U.S. Senate: The Civil War: The Senate’s Story,” Senate.gov, April 25, 2018, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/civil_war/LincolnEm….

- ^ “U.S. Senate: The Civil War: The Senate’s Story,” www.senate.gov, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Civil_War_E….

- ^ “History of the U.S. Capitol Building,” Architect of the Capitol, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/capitol-bu….

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War,” https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/SenatesCivil….

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ “The Civil War | Clara Barton Birthplace Museum,” Clara Barton Birthplace Museum, 2017, https://www.clarabartonbirthplace.org/the-civil-war/.

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ “Thomas Ustick Walter, 4th Architect of the Capitol | AOC,” www.aoc.gov, https://www.aoc.gov/about-us/history/architects-of-the-capitol/thomas-u….

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ Erin Nelson, “Then & Now: Capitol Building Superintendent’s Office,” Architect of the Capitol, March 27, 2018, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/then-now-capitol-buildi….

- ^ Margaret Wood, “Baking at the Capitol | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress,” blogs.loc.gov, May 26, 2015, https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2015/05/baking-at-the-capitol/.

- ^ Margaret Wood, “Baking at the Capitol | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress”

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ “30th to 39th Congresses (1847–1867) | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives,” history.house.gov, https://history.house.gov/Institution/Session-Dates/30-39/.

- ^ American History Central Staff, “Bull Run, Second Battle Of,” American History Central, September 3, 2020, https://www.americanhistorycentral.com/entries/second-battle-of-bull-ru….

- ^ Matt Guilfoyle, “Path to Capitol During the Civil War,” Architect of the Capitol, August 28, 2012, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/path-capitol-during-civ….

- ^ The national Republican. (Washington, DC), Sep. 2 1862. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn82014760/1862-09-02/ed-1/.

- ^ “Hospital Accommodations,” The Evening Star, September 11, 1862.

- ^ “The Civil War | Clara Barton Birthplace Museum,” Clara Barton Birthplace Museum

- ^ Senate Historical Office, “The Senate’s Civil War”

- ^ “History of the U.S. Capitol Building,” Architect of the Capitol

- ^ “U.S. Senate: The Civil War: The Senate’s Story”

- ^ Matt Guilfoyle, “Path to Capitol During the Civil War”

- ^ Matt Guilfoyle, “Path to Capitol During the Civil War”

- ^ Erin Nelson, “Then & Now: Capitol Building Superintendent’s Office”

- ^ “History of the U.S. Capitol Building,” Architect of the Capitol

- ^ “30th to 39th Congresses (1847–1867) | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives”

- ^ Philadelphia Press, October 2, 1898, https://www.legendsofamerica.com/ah-capitolghosts/.

- ^ “National Statuary Hall,” aoc.gov, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/buildings-grounds/capitol-bu….

- ^ “Capitol Night Watchmen Tell Weird Ghost Stories,” The Washington Post, July 8, 1906.

- ^ “10 Ghost Stories of the US Capitol,” ClotureClub.com, October 16, 2012, https://clotureclub.com/2012/10/10-ghost-stories-of-the-us-capitol/.

- ^ Erin Courtney, “Haunted Halls of Congress: 5 Creepy Capitol Legends,” aoc.gov, October 21, 2016, https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/blog/haunted-halls-congress-….

![[Union nurse Clara Barton] / Claflin's Photographic Gallery, 229 Main Street, Worcester, Mass. Photo of Clara Barton, taken in 1865](/sites/default/files/styles/embed/public/Clara%20Barton.jpg?itok=5sGeK7mM)

![[Union nurse Clara Barton] / Claflin's Photographic Gallery, 229 Main Street, Worcester, Mass. Photo of Clara Barton, taken in 1865](/sites/default/files/Clara%20Barton.jpg)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)