Michael Horsley's Washington of the 1980s

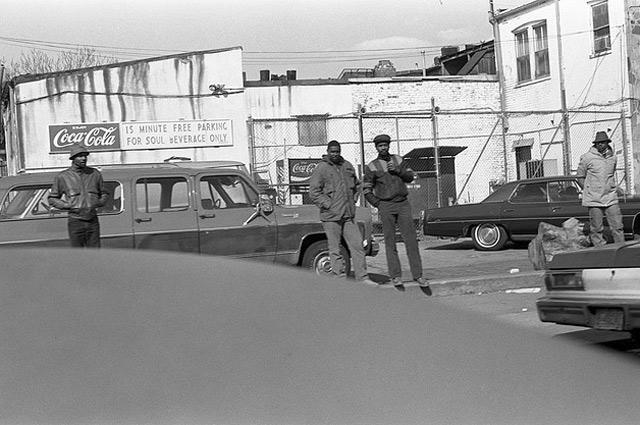

From 1984 to 1994 photographer Michael Horsley walked the streets of Washington, D.C., photographing the unseen and vanishing moments at a time when many inner-city neighborhoods still showed the effects of the 1968 riots. These images were tucked away in his private collection for almost 25 years until he published them on Flickr in 2010.

Horsley's Hidden Washington, D.C. collection (check it out on Flickr!) is a rare neighborhood-oriented photo archive of the nation's capital during the 1980s. In some cases, the physical landscape is almost unrecognizable today. In others, the scene is nearly the same now as it was then. Many of the photos are featured in WETA Television's documentary, Washington in the '80s.

We recently chatted with Horsley about his experiences taking the photos and his reflections on the changes he has witnessed in the years since.

Tell us a little about your background. Did you grow up in the D.C. area?

I’m originally from the west coast, from the San Francisco area and my dad got a job at the National Zoo. He was the curator of reptiles and my mom was a school teacher at a small private school here in D.C. We moved to upper Northwest when I was a young kid, right after the ’68 riots. So, I’ve been here ever since Vince Lombardi was the coach of the Redskins. I grew up around the same time as Henry Rollins and Ian MacKay. I wasn’t really part of the hard core music scene but I remember that whole era.

How did you get interested in photography?

I was into filmmaking in high school [at the Field School] and I found I really liked the image-making part of filmmaking. So, I started to gravitate towards photography as a way of documenting locations. I had a really good photography teacher in high school as well.

How did you come to take pictures on 14th St. and in the surrounding neighborhoods?

It’s kind of indirectly related to what else was going on in D.C. at that time – particularly with my generation – and the whole punk rock movement. I noticed a lot of my fellow photographers were doing pictures of bands and things like that and I kind of thought at the time that I didn’t want to take pictures of other people doing things. I wanted to find what my own thing was. I couldn’t afford to go to some exotic location so I ended up wandering around the street. D.C. was a very different place back then. So, I just started learning how to use that as my subject matter.

When you say you were learning to use the city as your subject matter, were you looking for specific things or were you just photographing whatever you saw?

A little bit of both. I was perhaps over-educated in the arts. I was going to the Corcoran at that point [the mid 1980s] and I was very influenced by other street photographers, particularly guys like William Eggleston and William Christenberry and Walker Evans. Also, I was trying to be kind of arty. I would be taking some arty shot and then I’d see a building and think, “Oh that looks kind of cool.” So, I’d take a picture of that and then go on and work on some kind of angular looking composition. Then I’d see another. “Wow, that looks like it’s about to be torn down.” Or, “This is a weird thing.” So, I started building up that awareness doing that. My heart was still trying to make some sort of artistic statement but my feet were making me kind of wander around the city, just exploring. I wasn’t really that brave but I definitely walked the streets. At the time, I didn’t have a lot of skill interacting with subjects but I would see things. Going to the Corcoran at that time, I felt like I got the type of education where I was responsible for not embellishing the subject matter.

Some of the neighborhoods you were photographing had very high crime rates. Did you feel as though you could be putting yourself at risk by carrying a camera?

Constantly. You know, having a camera around your neck is a commodity. You can swipe it off somebody and go buy five dollars worth of crack cocaine. I don’t want to overplay the danger but I think even today, I don’t realize how dangerous it could have been. Everybody of that era can remember it seemed violent and it could be violent at any given time.

The drug use and the prostitution were almost institutional at that point. There were open air drug markets. There was an open air heroin market at 11th and U St. I just would never get close to that kind of stuff. You just knew not to mess with it. That’s why if you look at a couple of my pictures of people standing around they’re kind of weirdly composed because I did what they call shooting from the hip, when you pre-focus your camera and just kind of point it in a direction. And, also, it’s kind of out of respect for people. I didn’t want to just come up and slam a camera in their face.

I used to live at 14th and T St. and I had a knife pulled on me because some prostitute was running away from her pimp and I didn’t realize what was happening. I didn’t have the street sense then so I was like, “Hey, what are you doing?” He pulls a knife, “Stay out of it. This is none of your business.” The building I was living in was crazy like that.

Is your old building still there?

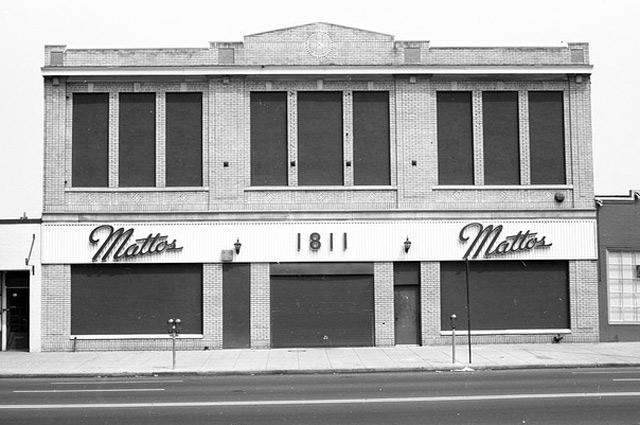

Yeah, it’s Café St. Ex! That place had kind of an off-the-grid coffee house and then I lived upstairs. Then, right next door we had kind of a squatter theater space. Then there’s the Source Theater. I’ve got a picture of what is now the Black Cat. It’s this auto repair place, which was called Mattos. I had no idea it would become a nightclub.

In those days, the gay and art communities were the only white people living east of 16th St. I don't mean to imply that these groups consciously tried to gentrify and drive out the predominant African Amercian population, which had been there for years. Far from it. Many of us artists chose to live in these areas because they were inexpensive. Washington was a small city at the time and many communities such as the gay, artist, African American, jazz and others supported each other. I really feel that’s part of why 14th St. ended up being the way it is, today [with a vibrant music and theater scene]. There were a couple of theater companies and that’s what attracted me to the 14th St. area, but upper class whites tended to avoid that area of the city.

Were you conscious of the power of your work at the time?

A lot of this work didn’t make a big impression on me until I looked at it much, much later. During that big snow storm [in 2010] when we all got stuck in our houses, I started scanning my archive and I noticed, buried in all my other photos were these pictures of D.C. I remembered taking them but they really started to speak to me much more than some of the more contrived arty work that I was doing at the same time. They were much more honest.

Did you anticipate the level of response the collection would garner?

Not at all, actually. The power of social media and crowd sourcing has been really amazing to me.

One thing that I think is kind of funny is that there were some graffiti taggers that found my Flickr site and they were like, “Man, check out this guy’s stuff! He took a picture of this. I remember that building!” Different people’s tags are in the background of some of these photos. I didn’t realize it at the time. I wish there was more of that, actually – people who knew that world and could identify some things. There’s still some hidden data in there.

Since I put the collection out there, I’ve had a lot of conversations with longtime African American D.C. residents and they’re very grateful that the D.C. that I depict is the world they experienced. I’ve been asked that a lot, “Do I feel like I’m exploiting people or whatever?” By and large people who are from that time period and from that community didn’t realize that their world had been photographed at all. So, I’ve had some really positive experiences with that afterwards.

I spent hours on Google maps trying to figure out the metadata, pinpointing where the photographs were taken. Online people will sometimes correct something and I realize, “Oh, yeah, I put the wrong thing in there.” Then other times I’ll get in sort of a tussle back and forth with somebody. “No, no. That’s the southeast corner of 9th and H St.” I’m like, “No, I was there. You’re wrong.” [LAUGH]

Do you have a favorite photograph in the collection?

I think the one that moves me the most is the picture of the homeless couple sleeping in the bus stop. I remember at the time I was really trying to learn how to do night photography by using special developing chemicals. I was wandering the streets really late at night. It was really a lonely occupation. I remember being at 14th and P St. and I remember seeing this couple huddled there. I can still almost feel what it felt like at that time when I took the pictures – kind of a tingling up my back. I remember being conscious of being very respectful to not disturb them, to gently come up and take a couple of shots. I made a print and didn’t think much about it. But then 20 years later I scanned the slide – I scanned the negative – and I had it blown up to 100% on my screen and I was doing spotting and retouching and fixing the negative. It was all scratched. I really looked at it really close and I could see paper cups on the ground and cigarette wrappers and urine and bottles. It’s just like, “Wow. This is such a still life. These people are just huddled there. Obviously they’re homeless but they’re people.” I struggled with that but there’s not much I could do about it. It’s emblematic of the theme. At least I documented it. I gave them kind of a face, a voice.

Did you pickup on the fact that you were a social documentarian at the time or did that realization came later?

When I went up and down 14th St., I didn’t know it was going to get the way it is today. I had no clue. I never gave it much of a thought. I just thought, “It’s the way it is—down and out.” But there’s some subject matter that, yeah, definitely I knew, “I’ve gotta take a picture of this.”

I could feel that D.C. was changing. It had come from something. White flight, the riots, I could kind of smell the burnt wood in the air 20 years later. There’s something kind of magical and scary about it at the same time. They say that fear – there’s a part of your brain where it burns into the circuitry. When I go around certain streets, I still feel like, “Oh, my god.” Yeah, it’s just something that happens to me. I can’t believe this friend of mine is opening up a bar right where there used to be a crack neighborhood.

When you look at your photos now are there any thoughts of, “Oh, I wish I would’ve gotten this shot or that shot”?

I wish I had understood more of the history and was a little bit more conscious of what I was documenting. I did a little bit over here and I did a little bit over there. I went to Arlington. I drove to Baltimore. I was a little bit… I don’t want to say unfocused but I didn’t think thematically or sequentially about stuff. Also, it really would’ve been great if I could’ve learned to be more engaged with the people and get their stories and their images but I don’t know how you do that. How do you befriend drug dealers?

To just sum up, do you have any other reflections on that time or the changes in D.C. since then?

The one thing is that I do miss is the edginess of the city but I also appreciate the economic development that’s happened. It’s kind of revitalized the city and made it into something that’s more than just Georgetown and Adams Morgan. At the same time, I and many others like me in my generation don’t really like a lot of how real estate is kind of co-opting artistic districts and using it to promote their business purposes. They’ll do lip service to supporting arts.

I think the last note is I’m really hopeful that younger people who are in their 20s now like I was then can continue to document what their world is. I don’t have the same vision I had then. I’ve moved on to different things. For every hipster moving in, hopefully there’s another person out there with a critical view and an artistic vision to see things who values documenting things. That’s what I would like to leave people off with – I thought that I had to go to Africa and Europe to take cool pictures but I was stuck going to Baltimore and Arlington and D.C. I kind of hope somebody does the same thing for their generation. It may be a different subject matter. It might not be the exact same thing of urban decay but there’s something else out there that they need to photograph.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)