When the Baltimore Sun was Washington's Most Visible Newspaper

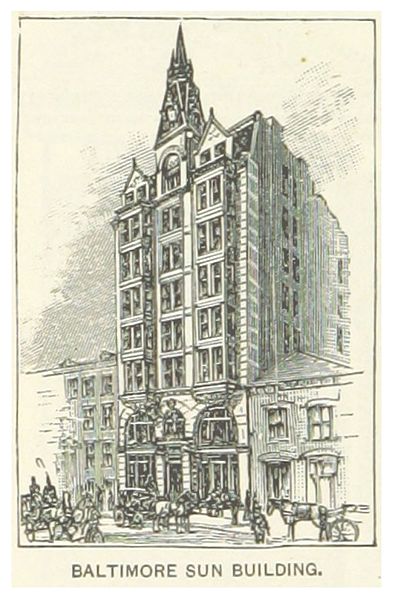

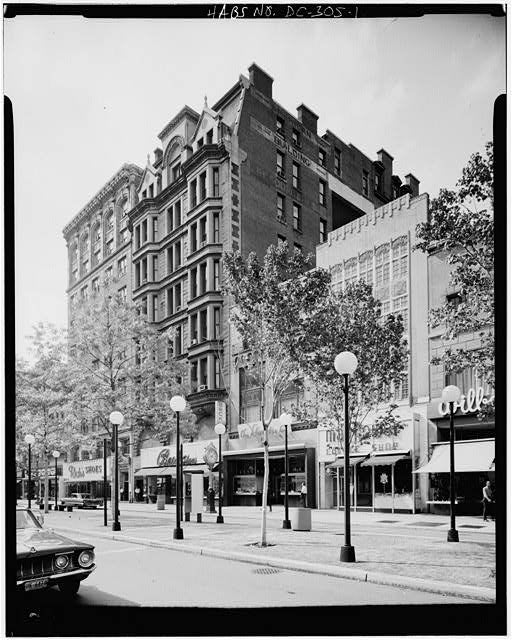

One of Washington, D.C.’s defining characteristics is the architecture. Both residents and tourists alike can be found marveling at the U.S. Capitol, snapping pictures of the White House or enjoying the 18th and 19th century charm of Georgetown. However, in a city known for height restrictions, many often miss a prime example of American architectural innovation right in the middle of downtown: The Sun Building at 1317 F Street NW, the oldest skyscraper in Washington, D.C. and, some have argued, the oldest still-standing skyscraper in the country. While the latter claim is up for debate, few would dispute the idea that 1317 F St. is architecturally significant. In 1987, archeologist Hershel Shanks went so far as to say that “among old, tall buildings that have survived, only two rival the Sun Building”: New York’s Flatiron Building, built in 1902, and Chicago’s Monadnock Building, built in 1891.[1] Still, D.C.’s oldest skyscraper is largely overlooked today.

To an extent, the oversight isn’t surprising. At 116 feet tall, the building is surpassed by many others in the neighborhood today. But back when it was built in the 1880s, 1317 F Street was a shining example of progress – vertical and otherwise.

By the latter half of the 1800s, Arunah Shepherdson Abell’s Baltimore Sun was one of the nation’s premiere newspapers, providing “Light for All” its readers.[2] Pretty much since its inception in 1837, The Sun kept a Washington correspondent and by 1872, started a full-fledged Washington bureau based at 1418 F Street NW.[3] After ten years, the increasingly influential Sun had outgrown the 1400 block of F Street, an area which by then was known as “newspaper row,”[4] and was looking for bold new digs to enhance its Capital presence. Abell didn’t have to look far. A vacant lot in the 1300 block F Street represented real estate pay dirt.[5] Still just blocks away from the Treasury Department and The White House, the new Sun Building would have an unmistakably lofty perch.

With a choice location selected, the newspaper hired one of the nation’s preeminent architects, Alfred Mullet, to design a building to be exemplary of “a major American newspaper in the Nation's Capital.”[6] Known for his designs of federal buildings, examples of Mullet’s work could be found all over the country, including Washington where construction on his latest project – the new State, War and Navy Building, now known as the Eisenhower Executive Office Building – was underway.[7]

For the Sun Building, Mullett’s design used two groundbreaking features of the day. The first was a steel skeleton that allowed the architect to design a structure seven floors above a two-story ground-floor and mezzanine. The new technique was a great step forward from self-supporting masonry techniques that had been used for generations, and required that each upper floor be supported by walls with progressively thicker bases below.[1] The use of steel meant that masonry walls could be hung. As a result, the walls didn’t have to as thick and the building could be taller without collapsing under its own weight.[8] Second, to ensure that the entire building was accessible, Bullett incorporated steam elevators into his design, making the Sun building one of the first structures in Washington to use a passenger elevator.[9]

To crown the Sun Building a success, a majestic tower was added, making the svelte structure even taller, helping to usher in skyscraper aesthetics.[10] In addition to the building’s height, its interior and exterior touches made for a commanding debut. At first glance, revelers were given a lesson in corporate branding, with black-eyed susans (the Maryland state flower) etched into the edifice’s façade along with a prominent sunburst above the entryway.[11] Upon entering, visitors greeted by a “marble staircase, finished in bronze, with a passenger elevator on each side, the whole being separated from the corridor by a colonnade and entablature of bronzed iron, a treatment that is continued to the eight story.”[12]

The editorial staff of The Baltimore Sun was understandably effusive in praising what they considered “the most imposing private structure at the national capital … an example of beauty, strength, and proportion unexcelled even by the public structures of the government.”[13] To bolster these bold claims The Sun printed a congratulatory telegram from The Washington Evening Star, announcing “a new era in building in Washington,”[14] ushered in by “the most expensive private building”[15] in D.C. history. Uruguayan ambassador Pedro Requena Bermudez placed the Sun Building in an international context. In comparing the structure to homes of the London Times and Le Figaro of Paris, he proclaimed that no “finer newspaper building than that of The Sun”[16] existed. With a cutting edge Washington foothold, The Sun was prepared to provide “light for the nation,”[17] but new challenges would cause attention to be diverted elsewhere.

The Washington Evening Star announced "a new era in building," with the debut of the Sun Building.

In 1888, shortly after his newspaper celebrated its 50th anniversary, Arunah S. Abell died at the age of 81. He left behind a successful newspaper, an attention-grabbing D.C. outpost and an inequitable will.[18] Abell’s will stipulated that his estate be evenly divided among his five children and three grandchildren but with caveats in place for his daughters.[19] Abell’s only surviving son Walter and three grandsons assumed managerial control of the estate and The Sun but not the Sun Building, which they shared with Abell’s four daughters.[20] Conflict among Abell’s heirs simmered as his prized skyscraper became the main cog in a contested estate.[21]

In 1900 a “friendly suit” was filed in Baltimore on behalf of Abell’s daughters, who were seeking a more just division of their father’s estate.[22] Three years later, “by order of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia” the Sun Building was put up for sale through public auction. Done to put an end to the Abell family drama, the situation became more complicated when Walter Abell placed the winning bid, a bid far below the building’s market value.[23] In 1904, following a challenge from “another heir” the Sun Building was ordered auctioned yet again. After no bids were made at a price set by the “Equity Court” the dispute was finally solved when the building was sold to then tenant American Bank.[24]

In the subsequent decades, the Sun/American Bank Building, would house a wide array of tenants, including the Interstate Commerce Commission,[25] the FBI (before its move into the Department of Justice Building) and the office of Franklin Roosevelt's first Commerce Secretary Daniel Roper.[26]

As the twentieth century introduced newer designs, many nineteenth century skyscrapers moved from cityscape to memory – Manhattan’s first skyscraper, The Tower Building, was demolished in 1914[27] and Chicago’s Tacoma and Home Insurance buildings were razed in 1929 and 1931 respectively,[28] to name a few.

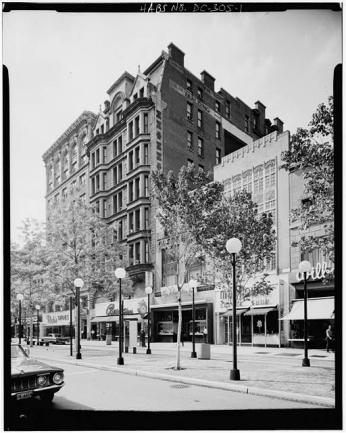

In Washington, however, the Sun Building, continued to stand over F St., albeit with some changes. The building was rendered less majestic – first in 1942 when the tower’s 15 ton spire was donated to the war effort, and then in 1950 when the tower itself was condemned and removed.[29] The burgeoning historic preservation movement would ultimately save the building from further demise, but it was not a clear cut process.[30]

In 1964 the Joint Landmarks Committee of the National Capital Planning Commission and the Commission of Fine Arts published a list of 292 sites to be preserved for their “visual beauty” and “cultural heritage.” In an exhaustive list that included everything from the Atlantic Building to Arlington Cemetery, the Sun Building was noticeably not listed.[31]

In 1966 Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act in order to protect “those places that define our past.”[32] This measure not only saved many buildings from the wrecking ball, it also inspired a reassessment of what makes a structure significant.

In the early 1980s, as the Sun Building’s centennial approached, its place in Washington’s history was reexamined. In 1982, the building underwent a $2 million restoration with special attention paid to the building’s uniqueness, its opulent iron stairway, original fireplaces and sunburst and sunflower motif.[33] Three years later, on March 27, 1985, the structure was added to the National Register of Historic Places, recognized as “a distinctive surviving example of the private practice work of Alfred Bult Mullett” and an “example of a new building type,” the skyscraper.[34]

Footnotes

- a, b Shanks, Hershel, “D.C._First In Skyscrapers?.” The Washington Post, July 12, 1987.https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1987/07/12/dc_first-in-…

- ^ “History of The Baltimore Sun.” The Baltimore Sun, September 12, 2012.http://www.baltimoresun.com/about/bal-about-sun-sunhistory-htmlstory.ht…

- ^ “History of The Baltimore Sun.” The Baltimore Sun, September 12, 2012.http://www.baltimoresun.com/about/bal-about-sun-sunhistory-htmlstory.ht…http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016824050/

- ^ “As early as 1871 there were 19 out-of-town newspaper offices in the area.” https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/85000650_text

- ^ The building’s lot, purchased in 1885 had doubled in value in just two short years.“From Washington: The Sun’s New Building.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 20, 1887, p. 1.

- ^ https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/85000650_texthttps://www.britannica.com/biography/Alfred-B-Mullett

- ^ https://historicsites.dcpreservation.org/items/show/571

- ^ https://www.history.com/topics/landmarks/home-insurance-building

- ^ https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/85000650_text

- ^ https://www.bizjournals.com/washington/stories/2000/10/16/focus8.htmlhttps://www.britannica.com/biography/Alfred-B-Mullett

- ^ https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/85000650_text

- ^ “From Washington: The Sun’s New Building.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 20, 1887, p. 1.

- ^ “Light For The Nation.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 25, 1887, p. 5.

- ^ “From Washington: The Sun’s New Building.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 20, 1887, p. 1.

- ^ “From Washington: The Sun’s New Building.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 20, 1887, p. 1.

- ^ “No Finer In The World.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), November 23, 1906. p. 14.

- ^ “Light For The Nation.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 25, 1887, p. 5.

- ^ https://www.baltimoresun.com/about/bal-about-sun-sunhistory-htmlstory.html“Sun Building Is Sold.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 9, 1903. P. 2

- ^ “Sun Building Is Sold.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 9, 1903. P. 2.

- ^ “Sun Building Is Sold.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 9, 1903. P. 2.

- ^ By 1903 the Sun Building was raking in $2,000 a month in rent, adjusted for inflation $60,000.“Sun Building At Auction.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), January 8, 1904. p. 8 “Light For the Nation: The Sun Opens House in Washington.” The Baltimore Sun. (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 25, 1887, p. 5. “Sun Building Is Sold.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 9, 1903. P. 2.

- ^ “Sun Building Is Sold.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 9, 1903. P. 2.

- ^ “Sun Building Is Sold.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 9, 1903. P. 2.“Sun Building At Auction.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), January 8, 1904. p. 8.

- ^ “F St. Building Is Purchased For $450,000.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 30, 1935. P. 3.

- ^ “Against The Fourth Section: Railroad Men Still Fighting the Long and Short-Haul Clause.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), April 6, 1887, p. 2.

- ^ Daniel Roper previously served as the chairman of Woodrow Wilson’s reelection campaign. As a lawyer, Woodrow Wilson work out of the Sun Building.https://millercenter.org/president/fdroosevelt/essays/roper-1933-secret…

- ^ Gray, Christopher. “Streetscapes/The Tower Building.” The New York Times, May 5, 1996.https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/05/realestate/streetscapes-the-tower-bu…

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/apr/02/worlds-first-skyscraper-…

- ^ “Steeple To Go To Scrap Pile.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), November 12, 1942. p. 19.“F Street Spire Will Be Added To Scrap Heap.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), October 24, 1942, p. 1.Wizda, Sharyn. “Tall Tales.” The Washington Post, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), June 28, 1992, p. W 11.https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NRHP/85000650_text

- ^ https://www.gsa.gov/blog/2015/05/15/Old-Penn-Station-the-Birth-of-Histo…

- ^ Von Eckardt, Wolf. “Group Asks Saving of Landmarks.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), November 9, 1964, p. A 1.

- ^ https://www.nps.gov/subjects/historicpreservation/national-historic-pre…

- ^ Visible from the street, the flowers are a prominent feature of the building. Some sources say they are black-eyed susans, the State Flower of Maryland, others say that they are sunflowers. Because of their height and appearance on the building, I err towards them being sunflowers.Jones, Carleton. “Restorers make new edition of Sun’s old building in D.C.” The Baltimore Sun, (ProQuest Historical Newspapers), October 5, 1982. p. C3.https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/58884925-1ceb-4f0e-91d3-60ca8f2f2…

- ^ https://npgallery.nps.gov/AssetDetail/58884925-1ceb-4f0e-91d3-60ca8f2f2…

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)