The First Sting: Did a New Tactic by D.C. Police Ensnare Criminals or Entice Crime?

They came from miles around: the robbers and thieves, burglars and pickpockets. On the evening of February 28, 1976, they arrived at the familiar warehouse off Bladensburg Road dressed to the nines. Over the past five months, most had frequented the offices of P.F.F. Inc to “fence” (or sell) all kinds of stolen goods to the slick mafiosos who ran it. Tonight was a celebration of their partnership. The Don himself was going to attend, and everyone wanted to look right.

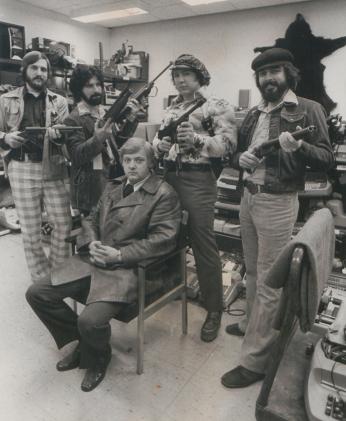

When the guests arrived, they were met with friendly faces. All the Italians were there, from smooth-talking Pasquale Larocca to tight-lipped muscle men like Angelo Lasagna and Rico Rigatone. Pasquale beamed, greeted them, and respectfully checked any weapons. A safety measure for the Don, he explained. As The Commodores played over the speaker, each guest came to meet the big man. “Bless you, my son,” he offered as they kissed his ring. Then the trap sprung. Police poured through every door, enveloping stunned partygoers. Each was cuffed, searched, and marched to U-Haul vans waiting out back. With soul music covering the commotion, Pasquale and his partners quickly reset the scene for the next wave of guests.[1]

The sham party was the culmination of “Operation Sting,” an intricate attempt to crack down on Washington’s stolen goods trade. For months, D.C. police and FBI agents ran a fencing operation in Northeast, buying $2.4 million in purloined property on behalf of a fictional Mafia crew. Police agencies had tried similar measures before, but nothing at this scale. Taking its name from the 1973 Oscar-winning movie, Operation Sting applied the long con to law enforcement, introducing “sting operation” to the American lexicon. With its cartoon names and hijinks, “Sting” reveled in the absurd. But behind the facade, the operation embodied something darker: the increased targeting of marginalized people by America’s criminal justice system.

Operation Sting was concocted by Lt. Robert Arscott, an officer in the Metropolitan Police Department’s Office Theft squad. To address a rise in stolen office equipment, Arscott rented a small K Street office and set up a fake typewriter fencing operation called “Urban Research Associates.” Amid Washington’s white-collar business district, Arscott’s operation got few takers, but he was hardly discouraged. In Fall 1975, he reached out to his superiors and contacts at the FBI, ATF, and Secret Service. Together, they planned a much larger effort.[2]

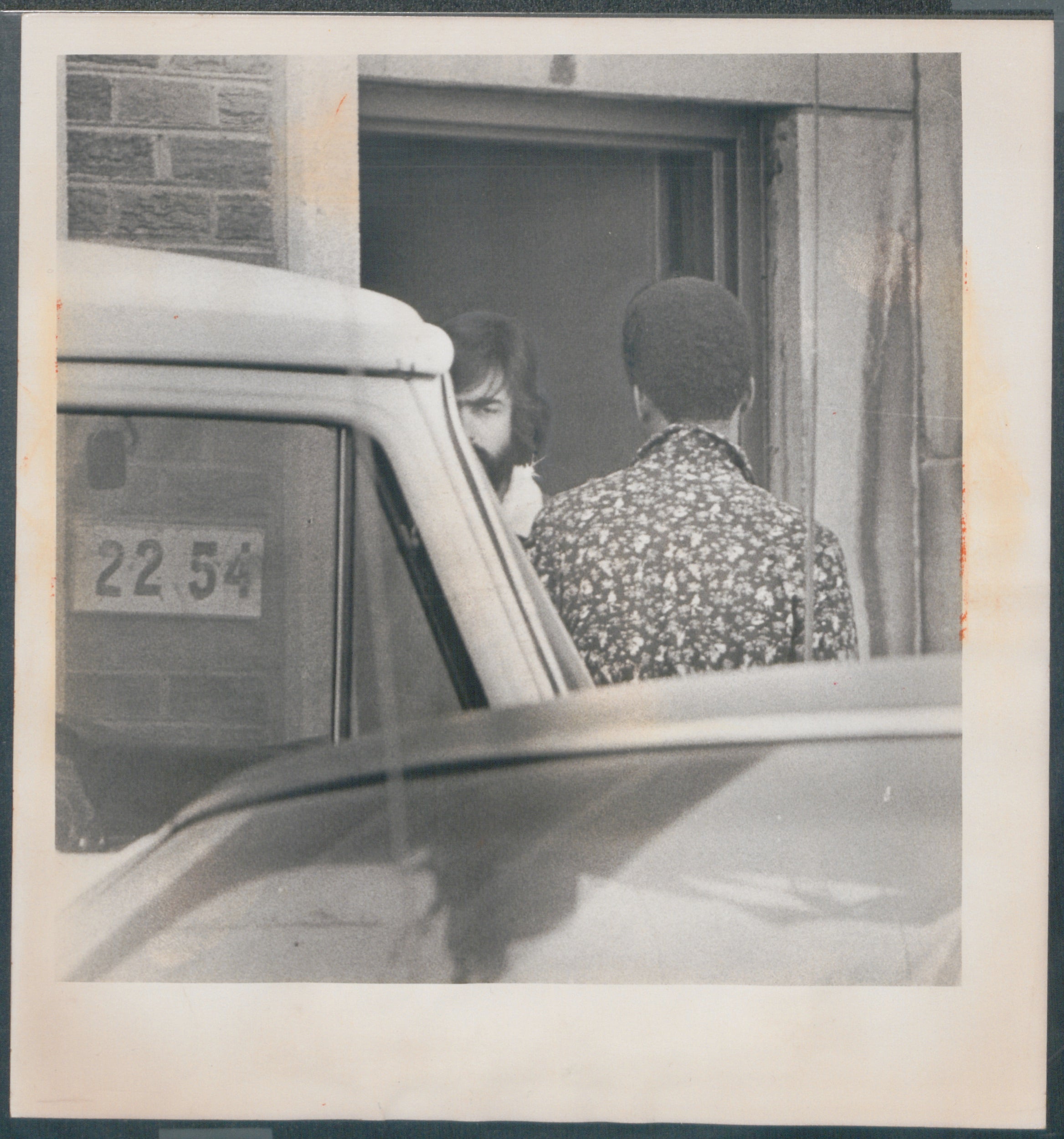

The inter-agency team rented a warehouse at 2254 25th Place NE in Washington’s heavily Black Langdon neighborhood. They named their new fencing operation “P.F.F. Inc,” meaning Police-FBI Fencing Incognito. To the rest of the world, however, the outfit would be “Pasquale’s Finest Fencing,” the new D.C. outpost of a New York mob family. To play the title role of Pasquale Larocca, Arscott chose Patrick Lilly, a charismatic detective with a penchant for undercover work. Dying his hair jet black, Lilly joined a team of other faux-mafiosos with personalities ripped from The Godfather.[3]

To get the operation running, D.C. police sent undercover “scouts” to spread the word along the 14th Street corridor, an impoverished Black community that had been devastated by riots after the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King. Interest was slow to build, so “Pasquale” and his crew paid handsomely for anything they could get their hands on. One man sold P.F.F. a legal handgun for twice what he had paid for it at the Montgomery Ward department store. As news of such prices spread, business at P.F.F. picked up.[4]

The MPD-led team funneled their newfound clients through a process designed to capture every detail of every sale. Prospective sellers had to call Pasquale from a payphone at the Amoco gas station near the warehouse. Once inside, they were asked to supply a drivers’ license, birth certificate, or other form of ID to prove (ironically, of course) that they were not an undercover cop. Only then did the fencing begin. Every sale was recorded by cameras hidden throughout the P.F.F. headquarters, most notably behind a two-way mirror covered withPlayboy centerfolds to draw sellers’ faces into view. Pasquale also offered clients glasses of whiskey, which were dusted for fingerprints. Once the sale was complete, each stolen good was shipped from the warehouse and processed as evidence.[5]

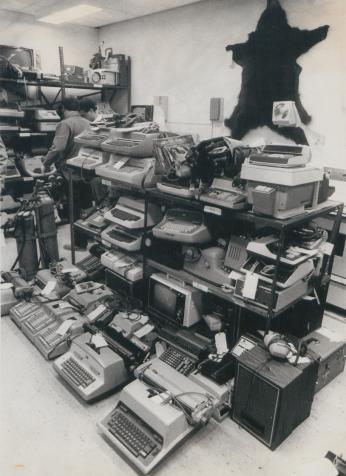

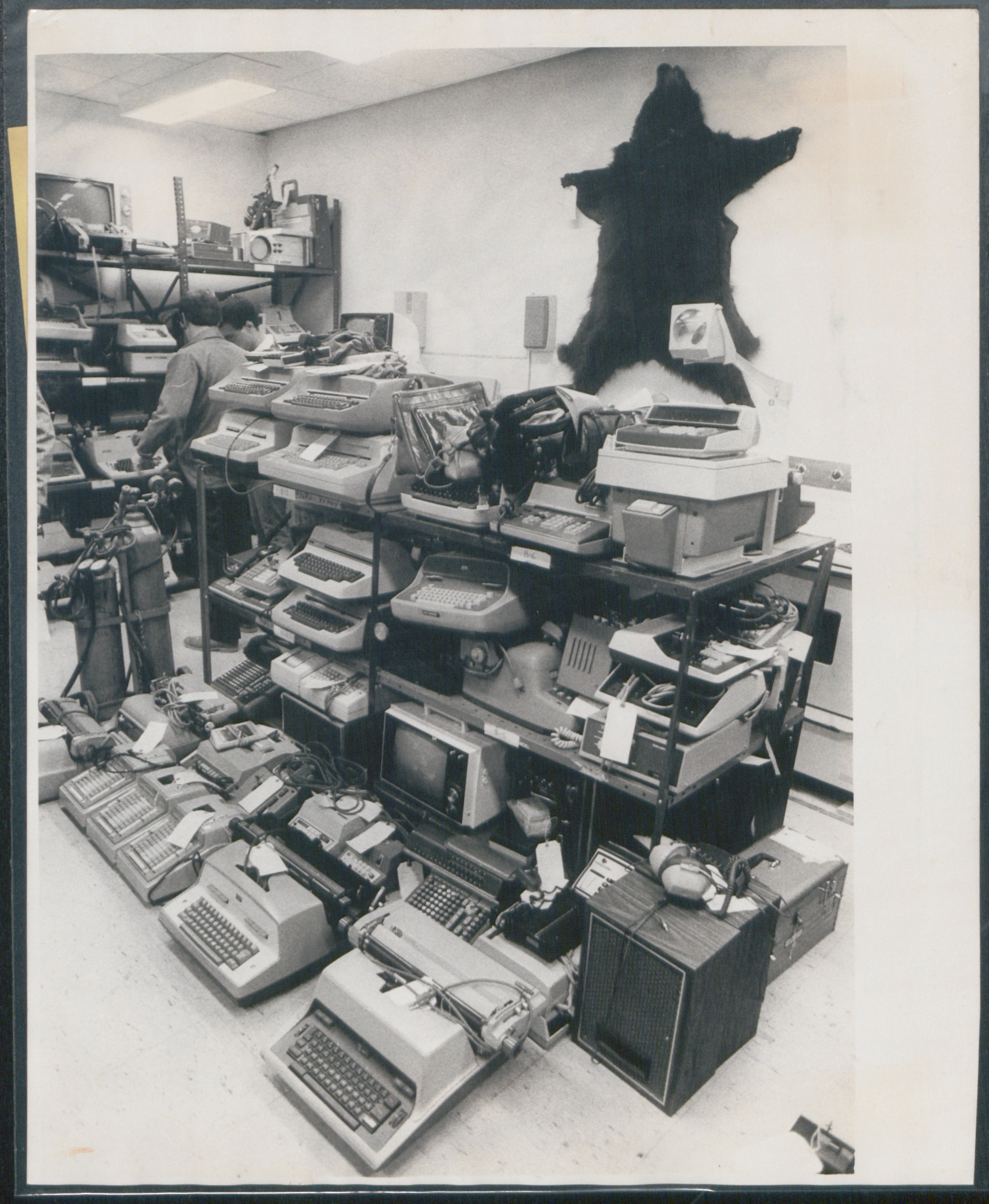

Soon P.F.F. had more sellers than they knew what to do with. Employees at the Amoco station became frustrated with the crowds constantly gathering at their payphone. They dumped a dead racoon inside the booth, but it hardly made a difference. At one point, 15 cars lined up outside 2254 25th Place waiting for Pasquale, disrupting business for the legitimate firms on the block. But the goods kept coming. They included common items like televisions, but also more exotic fare like air hockey tables, a bearskin rug, an entire ECG machine from Prince George’s Hospital Center, and $1.2 million in federal government checks taken from a vault at the Department of Housing and Urban Development. One seller allegedly fenced his own defense attorney’s wallet. A postal worker even drove up to sell checks directly out of his USPS truck.[6]

To keep the front alive, Pasquale and his associates embraced their Mafia alter-egos. They boasted about their pretend violent pasts, from killing someone’s “old lady” to throwing acid in a rival’s face. None spoke Italian, but they talked and sang incessantly in pseudo-Italian gibberish that they assumed was good enough to trick their clients. The men eventually took to preparing meatballs for their guests, rendered comically spicy through large amounts of Tabasco sauce. If the clients demurred, they were warned of the consequences of insulting a mobster: “Have a meatball, you hurt Pasquale’s feelings if you no have a meatball.”[7]

By February 1976, P.F.F. Inc reached the end of its line. Though their above-market rates faded once business boomed, the team still spent over $67,000 in taxpayer money on stolen property. Their agencies were reluctant to offer more. The administrative burden was also becoming unmanageable, with over 225 sellers and 20,000 transactions to catalog. The MPD and FBI decided to wrap-up the operation in style with the fake Mafia party, which ensnared 70 of P.F.F.’s clients. As Det. Lilly shed his Pasquale persona, he laughed at the stunned responses from his erstwhile associates. “Life’s just a game,” he said to a handcuffed seller, “and you’re one of the losers.” In the following days, another 50 sellers were arrested.[8]

When the MPD revealed the operation, they received unprecedented public interest. Local news fawned over the project, entertaining their audiences with Pasquale and his team’s antics. President Ford invited the officers to the White House. The attention became so overwhelming that the MPD had to impose an interview ban.[9] But though they postured as reluctant subjects, participants in “the Sting” used their time in the spotlight to make a specific argument about crime in Washington. They claimed that, while police were doing their jobs, overly lenient courts were letting bad guys off easy. MPD chief Maurice Cullinane targeted his ire on the 1966 Bail Reform Act, which made it easier for D.C. suspects to be released before trial. Pointing to the many Sting suspects who were out on bail, parole, or probation when arrested, Cullinane told Congress “We’ve got to do something about the bail reform act.”[10] The officer who played Rico Rigatone put it more simply. “They’ve got a brand new jail. Fill it up.”[11]

But not all Washingtonians saw Operation Sting as a triumph worth setting policy around. For one thing, D.C.’s Italian American community was not amused. In letters to the Washington Post, Italians like James LaRocca denounced the operation for its demeaning use of stereotypes:

“Ethnic jokes and the false stereotypes they are built upon are always offensive. When appearing in popular literature and movies of the day, they must be tolerated as one of the prices of free speech- however ill-founded or unfair they may be. But when perpetuated by official behavior, there is no ground upon which they can be tolerated. The FBI and D.C. police owe all Americans with Italian names an apology.”[12]

Others questioned whether Sting had actually worked to stop the sale of stolen goods or instead made it easier. The MPD said that the items they purchased would have been stolen regardless, but they undercut their case by arguing that fences in general were “the catalyst for burglars and thieves.”[13] Community groups also pointed out that a sizable portion of Sting sellers were drug addicts, many of whom had been turned away from the city’s overcrowded treatment centers. Summing up this perspective, another letter to the Post argued that “the Sting may have created new criminals, but little else and nothing of value.”[14]

The MPD and allied agencies were undeterred. In fact, they did it a second time. While Operation Sting was still running, the same team launched “Operation Got Ya Again,” fencing goods from a Shaw warehouse on the same block as Ben’s Chili Bowl. This time the undercover officers were Black, posing as mechanics-turned-fences working for “a Jew” called Mr. Rosencranz. When this operation was shut down in July 1976, dozens more sellers were arrested, including nine who had already been charged in Operation Sting. Nearly all suspects were poor Black Washingtonians, and a majority were past or present addicts. Many community activists were furious, even crashing a press conference in which the Got Ya Again undercover team was presented to the media.[15]

But those opposed to operations like Sting were fighting a losing battle. The arrest counts and positive media attention led dozens more cities to attempt similar operations, backed by generous federal funding. The veterans of Sting and Got Ya Again played a leading role in promoting these ventures, with one federal administrator calling them “missionaries” for large scale, interagency efforts. Like their model, subsequent stings primarily targeted, arrested, and incarcerated poor Black people in America’s declining urban centers, especially when their focus shifted from stolen goods to illegal drugs.[16] The Sting crew’s critiques of Washington’s criminal justice system also bore fruit, helping convince Congress to repeal the Bail Reform Act and dramatically toughen D.C.’s criminal code in the early 1980s.

By that time, “sting operation” had become a household term. For many, the name was painfully ironic. In the movie that gave Operation Sting its name, “the Sting” referred to a plot, an elaborate and illegal scheme to trick someone out of their money. A decade later, D.C. police had helped make “the sting,” with all the same elements of flair and deceit, a mainstay of law enforcement and the search for justice in the United States.

Footnotes

- ^ Alfred E. Lewis and Ron Shaffer, “Police, FBI Arrest 108 In Fake Fence Project,” Washington Post, March 1, 1976, A1, A2. Ron Shaffer, “'Bless You, My Son,' 'Don' Told Suspects,” Washington Post, March 5, 1976, C1, C8. “Gimme Shelter, the Thief Cried,” Washington Post, September 25, 1977, A1, A34, from Kevin Klose and Ron Shaffer, Surprise! Surprise!: How the Lawmen Conned the Thieves (New York: Viking, 1977). Sally Quinn, “Mustard, Tabasco, Easy on the Hamburger,” Washington Post, March 5, 1976, B1, B16.

- ^ “Birth of a Team Effort,” Washington Post, September 26, 1977, A1,A6, from Klose, Shaffer, Surprise!

- ^ Ron Shaffer, “Lawmen Besieged by Interviewers,” Washington Post, March 7, 1976, B1, B2. Godfather comparison made in Elizabeth Kai Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 210.

- ^ “Inside the Warehouse,” Washington Post, September 27, 1977, A1, A6 from Klose, Shaffer, Surprise!. “Man Seeking Cash is Stung,” Washington Post, March 7, 1976, B1, B2.

- ^ Ron Shaffer, “Business Was Brisk,” Washington Post, Mar 2, 1976, A1, A8. Timothy S. Robinson, “'Sting' Fence Served Whiskey, Tested Guns,” Washington Post, March 30, 1976, C1, C3.

- ^ Shaffer, “Business was Brisk.” Lewis and Shaffer, “Police, FBI Arrest.” Wallet fencing alleged in Shaffer, “Bless You.”

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Lewis and Shaffer, “Police, FBI Arrest.” Shaffer, “Lawmen Besieged.”

- ^ Shaffer, “Lawmen Besieged.” Lewis and Klose, “'Sting' Police Honored at White House,” Washington Post, July 14, 1976, A1, A4.

- ^ Timothy S. Robinson and Charles R. Babcock, “100 in 'Sting' on Bond, Parole,” Washington Post, April 9, 1976, A1, A8. Other examples of this argument being made can be found in Shaffer, “Bless You” and Lewis and Shaffer, “Police, FBI Arrest”

- ^ Rigatone quoted in Toni House, ”The ’Sweat Hogs’ Can’t Get Over What They Did,” Washington Star, March 4, 1976, B1, B4.

- ^ James Larocca, “Letters to the Editor,” Washington Post, March 13, 1976, A18. Similar sentiments are expressed in Lance Gay, “Italian Americans are Stung to the Quick by Lasagna & Co,” Washington Star, March 5, 1976, A1, B1.

- ^ Timothy S. Robinson, “The Fence: Elusive Criminal,” Washington Post, July 25, 1976, B1, B3.

- ^ Timothy S. Robinson and Alfred E. Lewis, “Officers Recount G.Y.A. Experiences,” Washington Post, July 10, 1976, B1, B2. W.M. Sandrige, ““Letters to the Editor,” Washington Post, March 13, 1976, A18.

- ^ Robinson, Lewis, “Officers Recount G.Y.A.” Timothy S. Robinson, “Officers Ran Phony Fence as H&H Trucking,” Washington Post, July 7, 1976, A1, A12. Timothy S. Robinson and Alfred E. Lewis, “Scores Arrested in 2d Operation, 'Got Ya Again',” Washington Post, July 7, 1976, A1, A12. Ruth Jenkins, “The Sting II,” Afro American, July 17, 1996, 15.

- ^ Hinton, From the War on Poverty, 209, 214-216.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)