Death Over the Potomac: A Mid-Air Plane Crash Leaves D.C. Looking for Answers

Ralph and Mildred Miller just wanted to get home. After an autumn trip to Europe in 1949, the Chevy Chase couple had dealt with 24-hours of delays as bad weather blocked their return to Maryland. But skies were clear on the morning of November 1. The Millers boarded Eastern Airlines Flight 537 from New York and flew south uneventfully.[1] But as they prepared to land at National Airport, their DC-4 airliner suddenly lurched left. The husband and wife felt a tremendous crash. Then they felt nothing at all.

Over the next three days, the bodies of Ralph, Mildred, and 53 other people were recovered from the frosty waters of the Potomac River. Morgues in D.C. and Alexandria struggled to process their soaked and mutilated remains. In the 40-year history of American aviation, no airplane crash had ever claimed so many lives.

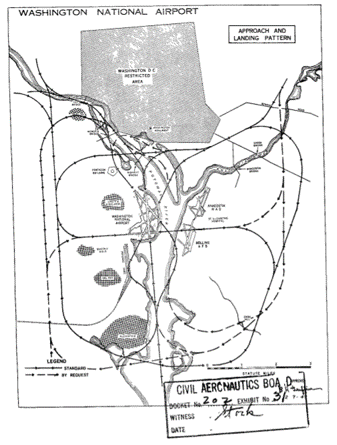

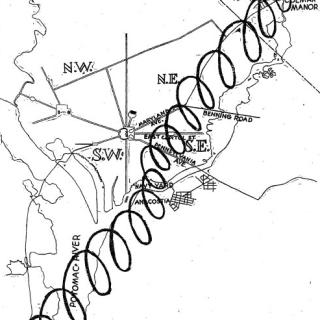

The immediate cause of the crash was no mystery. From their perch at National Airport, air traffic controllers had watched with horror as a P-38 fighter plane, surplus from World War II, descended on Flight 537 and crashed square into its fuselage. The controllers had yelled desperate orders for the P-38 to turn, but it never did. Investigators needed to know why.[2]

There was little out of the ordinary about Flight 537, but the plane it struck was hardly a fixture of the D.C. skies. Piloting the P-38 was Captain Erick Rios Bridoux, Bolivia’s director of civil aviation. Only 29, Rios spoke perfect English and was already considered his country’s best aviator. He came north to inspect the P-38, which Bolivia planned to purchase, and take it on a test flight. On November 1, he looped casually around Northern Virginia before preparing to land at National.[3] The tower told him to circle once, wait for another plan to land, and then do the same. Everything that followed became a subject of debate and litigation.

From the ground, motorists on the George Washington Parkway (then called the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway) heard a massive explosion above them. Within seconds, debris began landing all over the road and the Potomac. J. Donald Mayor jammed on his brakes. To him, it looked like pieces of paper were fluttering from the sky, but they were really shards of metal. He immediately pulled over and ran to the shoreline, where a 50-foot section of the plane was jammed into the mud. Six twisted legs stuck out from the ground. “There was no noise, no groans, or shouts,” he told reporters.

PEPCO workers on a lunch break got an even clearer and gorier view. Glancing up at the sky, C.W. Simpson saw Flight 537 go down, looking like “an acetylene torch had just cut the big plane right in half.” He and his co-workers ran into the water to look for survivors. Most of the bodies they encountered were already dead, but a few clung briefly to life, moaning in pain.

The back section of the plane, which PEPCO worker T.T. Williams entered, was particularly horrific. Half submerged, the tail contained a jumbled mix of broken bodies. “You couldn’t tell which feet or arms belonged to which people,” he said. Some portions of the plane that remained above water were splattered with blood and brains.[4]

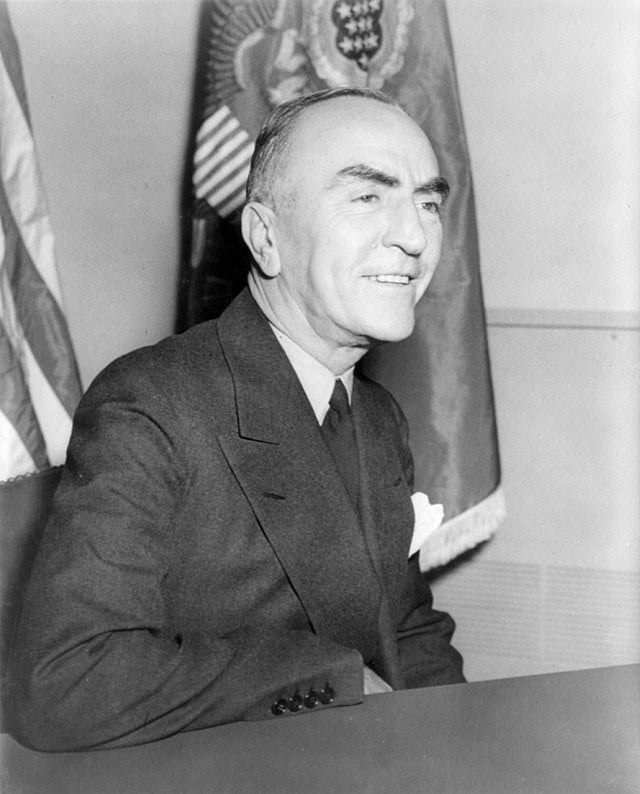

No one on the DC-4 survived more than a few hours. Their remains were brought to the Alexandria Armory, which the night before had hosted a joyous Halloween party for the city’s youngsters. Now coroners struggled to identify bodies.[5] Because of how expensive early air travel was, the victims were mostly notable and wealthy individuals. Chief among them was Rep. George Bates of Massachusetts, the ranking member on the House District Committee and a major advocate for Washington. He was returning to the Capital after a weekend with his family. Other casualties included Michael Kennedy, the former leader of New York’s Tammany Hall political machine, and beloved New Yorker cartoonist Helen Hokinson.[6]

However, one person survived the aerial inferno. It was Captain Rios, the pilot of the P-38. As his plane tumbled into the river, Rios was thrown through his cockpit window. Unable to swim out of the Potomac, Rios was saved by Sgt. Morris Flounlacker of Bolling Air Force Base, who lept in and dragged him to safety. The Bolivian had a broken back, shattered ribs, and severe cuts in his head. He soon developed pneumonia, and doctors gave him just a 60% chance to live. But Rios pulled through. As he regained consciousness, he had no idea what his plane had hit. When investigators told him about Flight 537, he was distraught. He said he “only wanted to die.”[7]

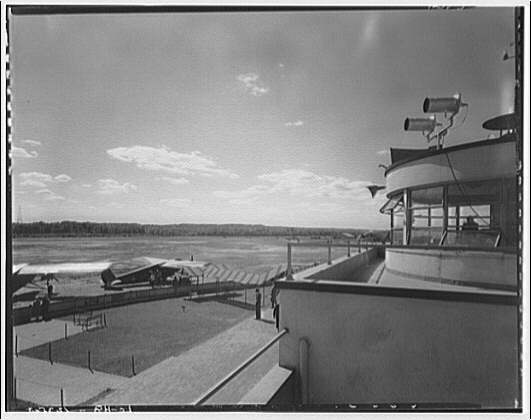

As investigators waited for Rios to recover, politicians and the public demanded changes to prevent similar crashes in the future. They focused on the problem of congestion. National Airport was notoriously overcrowded, and flights often had to be diverted as far as Philadelphia because they had no room to land. The large number of military planes, like the P-38, which were allowed to share National made the situation worse. For the sake of Washingtonians, and their own convenience, many members of Congress called for something to be done.[8]

Once Rios weaned off post-crash painkillers, experts from the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) asked him for answers. He said that he flew toward National Airport in a state of mild emergency, as his plane’s power seemed to be cutting out. He mentioned this to the tower and followed their orders exactly. He circled the airport, saw another plane land, and then made his descent. Suddenly, he heard someone from the tower frantically yell “Turn left!” A moment later, Rios said that he and his plane struck something unknown to him and began falling from the sky.[9]

Air traffic controllers, however, rebutted Rios’s story. They said that the Bolivian pilot never mentioned engine trouble, never circled National, and did not wait for another plane to land. When they saw him enter a steep dive toward the runway, they issued a “barrage of orders” to turn, which he never replied to. They finally told the Eastern Airlines flight to make a desperate turn to avoid a collision, but seconds too late to avoid disaster.[10]

When the CAA released their report in September 1950, they blamed Captain Rios. They wrote that the crash was caused by the “execution of a straight-in final approach by the P-38 pilot without obtaining proper clearance to land and without exercising necessary vigilance.” While the CAA said the tower should have warned Flight 537 earlier, they concluded that controllers could not have prevented the crash since Rios was not answering his radio. Meanwhile, they labelled the DC-4 faultless. In fact, the CAA absolved Eastern Airlines just 48 hours after the crash.[11]

But that was not the end of the story. After the crash, the family of Ralph and Mildred Miller, along with the heirs’ of other victims, sued Rios, Eastern Airlines, and the U.S. government for damages. In 1953 a federal judge decided that a jury should definitely decide who was at fault, regardless of what the CAA report said.

What they concluded was shocking. Rios was not to blame- Eastern Airlines was. Flight 537 never received authorization to land, and in fact took a shortcut to move into National’s airspace. Its pilots also took no caution to let other planes know where it was. Rios could have been more careful, but the jury also acknowledged that he did not in fact cut the line to land. A military B-25 bomber had done a simulated practice landing just moments before, and that was the plane Rios probably thought he was supposed to wait for.[12]

Eastern Airlines was furious. They fought the ruling all the way to the Supreme Court, finally losing in 1957.[13] Rios, however, was ecstatic. He had been devastated by the crash, with a shattered body and reputation. When a coup toppled Bolivia’s government in 1952, he had to flee for his life. But the jury’s verdict redeemed him. He shared his joy with the Washington Post, beaming that “I am convinced now that, in the United States, you find the truth.”[14]

Though the pilots of Flight 537, and not overcrowding at National Airport, were ultimately held responsible for the crash, Washington policy-makers acted anyway. Just two weeks after the crash, the CAA told Congress that D.C. needed another major airport. A bill to do just that had been sitting dormant for months, but the horror of the crash, and the death of their colleague Rep. Bates, shocked the House and Senate into action. They passed the Washington Airport Act to build a new airport in the D.C. region.

Though it took 12 years of fighting between Maryland and Virginia to select its location and construct the facility, Dulles International Airport finally opened in 1962.[15] In his speech opening Dulles, President John F. Kennedy congratulated “the citizens of America, who, in their joint capacity as citizens of the greatest free country, have made this airport possible.”[16] His words were especially true for Ralph and Mildred Miller and the passengers who died with them, who together did more than almost anyone to bring Dulles Airport into existence.

Footnotes

- ^ “Chevy Chase Couple Took DC-4 After Delay In Flight From Europe”, Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A4.

- ^ “40 Feared Killed in Midair Collision of Airliner and P-38 Near Airport Here,” Evening Star, November 1, 1949, A1, A3. “55 Killed When P-38 Wrecks Airliner Near National Airport,” Washington Post, November 2, 1949, 1, 10.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ “Pieces of Metal Fell Like Paper, Witness to Air Disaster Says,” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A5.

- ^ “Morgues for Air Victims Set Up Under Old Jurisdictional Plan,” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A6.

- ^ “Bates Boarded Plane After Important Work Delayed Trip Here,’” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A4. “Michael J. Kennedy, Crash Victim, Was Veteran Politician,” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A5. “Helen Hokinson Met Death On Rare Trip From New York,” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A4.

- ^ “Last Three Bodies Sought; CAA Clears Airline in Crash,” Evening Star, November 3, 1949, A1, A3. “Firm Says Bolivians Accepted Risk for Any P-38 Damages,” Evening Star, November 12, 1949, A1, A3. “P-38 Pilot ‘Much Improved,’” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A1, A5. “Crash Investigators to Study P-38 Radio; All Bodies Recovered,” Evening Star, November 4, 1949, A3. Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day,” November 5, 1949.

- ^ “Rickenbacker Urges Civilian and Military Planes Be Separated,” Evening Star, November 4, 1949, A3. “Law Sought to Keep Military Planes Off Commercial Airways,” Evening Star, November 2, 1949, A6. John London, “Another Major Airport Urged In CAA Report,” Washington Post, November 20, 1949, M1.

- ^ Benjamin Bradlee, “2 1/2-Page Statement By Bolivian Flier Makes No Mention Of Eastern DC-4,” Washington Post, November 6, 1949, M1. Sy Fishbein, “Crashed P-38 Pilot Implies Power Failed,” Washington Post, November 7, 1949, 1. “Rios Denies Blame In Crash Killing 55,” New York Times, December 29, 1949, 13. “Bridous [sic] Tells Of Air Crash Fatal to 55,” Washington Post, January 28, 1953, 3.

- ^ “Air Traffic Chief Testifies Rios Obeyed Order,” Evening Star, November 10, 1949, A1, A3. “Two Last-Minute Instructions Given, Officials Declare: Warnings Lost on P-38 Pilot,” Washington Post, November 2, 1949, 1.

- ^ Benjamin Bradlee, “P-38 Pilot Blamed for Air Tragedy Killing 55,” Washington Post, September 27, 1950, B1. “Last Three Bodies,” Evening Star.

- ^ “Suit for Damages In Bridoux Crash On Trial Monday,” Washington Post, January 7, 1953, 22. “Jury Chosen To Hear Air Tragedy Suit,” Washington Post, January 13, 1953, 15. Joseph Paull, “Crash Killing 55 Blamed On Airline,” Washington Post, March 14, 1953, 1.

- ^ “Appeals Court to Be Asked To Reconsider Crash Case,” Washington Post, February 19, 1955, 3. “Supreme Court Setting Record for Fast Action,” Evening Star, April 23, 1957, A7.

- ^ Paull, “Crash Killing”

- ^ London, “Another Major Airport.” Mechlin Moore, “Airport Debate Is 8 Years Old,” Washington Post, June 10, 1957, 10.

- ^ John F. Kennedy, “Remarks At The Dedication Of The Dulles International Airport,” recorded in Chantilly, Virginia, November 17, 1962: https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKWHA/1962/JFKWHA-143-009/JFKWHA-143-009

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)