President Harding and The Vagabonds

"Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and President Harding walk into the woods of western Maryland” sounds like the setup of a supremely corny dad joke, but it’s a scene that really happened in the summer of 1921. President Harding joined “the Vagabonds,” as they called themselves, on their annual camping trip at the foot of the mountains in Western Maryland.

The Vagabonds were Henry Ford (of Model-T fame), inventor Thomas Edison, tire manufacturer Harvey Firestone, and John Burroughs, an early environmentalist and conservationist. A 1915 road trip through California became an annual expedition of “motor camping caravans” that took them all over the country.1

Burrough died in March, 1921, leaving “a vacancy” in the group. At that moment, the Vagabonds were seeking a bit of favorable press coverage, and Harvey Firestone found a “surefire” way to attract it. He wrote to Edison that with the help of a mutual friend and “some of our camping books” he had enticed President Harding and the First Lady to join them that summer.2 Reporters would follow like flies to honey.

For his part, Harding “was pleased to accept the honor” and retreat from Washington’s noise to “live the simple life,” at least for a few days.3

Firestone, the host of the 1921 trip, immediately began planning. Harding had stipulated that he could not be more than a few hours from Washington, and Firestone proposed a few locations along the Potomac. Edison shot them down, saying the location should be “wild and secluded” to keep crowds out.

The Vagabonds then looked northwest to the tiny Maryland town of Pectonville, “probably one of the least traversed sections in the entire country.”4 Though a busy road passed nearby, the only access to the campsite was via a bridge on private land that was easily guarded by Secret Service agents.

Edison also took interest in Harding’s communication with Washington. To keep the President as close to camp as possible, he tried to dispatch a radio outfit to Maryland, as well as a temporary secret code for Harding to use. Harding was not keen on it at all: “One of the attractive features of the camping party,” he wrote, “is freedom from all such things.”5

Preparations for the President’s stay occupied all of Firestone’s attention. The day before Harding’s arrival, preparations were still underway. A score of reporters and Secret Service agents would be following, as well as a “camera man for the film services and picture services,” ballooning the number of campers, who needed to be comfortably fed and housed.6

Scouting parties searched for the best hiking routes. Ford set up smudge pots to dispel the clouds of mosquitoes. Firestone had arranged for 40 cots but hadn’t brought any bedding beyond the rough blankets the Vagabonds had always used. Clara Ford was horrified—the President deserved better than that! She “dispatched staffers to Hagerstown” to purchase softer bedding.7 The President might have only been staying for a weekend, but everything had to be perfect.

On Saturday, July 23, Harding met the Vagabonds in Funkstown, halfway to Pectonville. After pleasant introductions, he rode the rest of the way in a car with Firestone and Edison. Still insulted at having his radio idea shut down, Edison openly sulked the entire drive. Firestone was mortified, but Harding seemed to take it in stride, offering the inventor some chewing tobacco.

Edison grudgingly accepted, muttering, “Any man who chews tobacco is all right.”8

The wilderness vacation began unsteadily. Florence Harding abruptly came down with a cold and could not come, much to the disappointment of the Vagabonds’ wives. The White House notified Firestone that the President would only stay two days—which were heavily programmed for the press’ benefit.

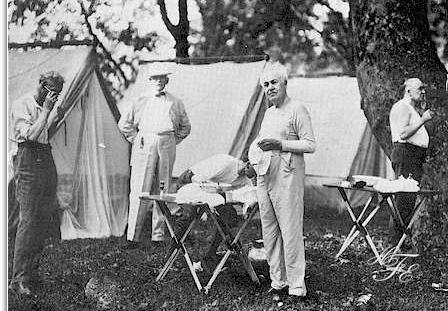

The campground itself, though, was a perfect getaway. The only building around was a “little log hut” without occupants, while green canvas tents rowed up with “military” neatness opposite it. The water of Licking Creek bubbled and ran freely on one side, and the Blue Ridge Mountains were not far on the other.

“Cares of state, financial worries, and new inventions were dismissed” for the weekend, as the only “important daily functions” became “breakfast, lunchon, and dinner."9

Though newspaper headlines proclaimed that “President Harding Thoroughly Enjoys ‘Roughing It’ in [the] Mountains,” he was by no means doing that.10 The Vagabonds camped in style, moving in “a caravan of automobiles and motor trucks” that could accommodate more than 40 people. And they needed it, too.

Two specially built trucks traveled with them: one housed two refrigerators with “several hundred pounds of meat, butter, eggs, milk and melons, and 100 dressed chickens.” The second was “a ‘kitchen cabinet’ on wheels.” It was full of every utensil, cup, and crockery a cook might need. The back folded down into a table.

Three more large trucks toted “tents, chairs, and other camp parts.” In all, the caravan contained 20 tents with canvas floors, 50 cots, and “scores” of blankets.11 12 The campground itself was lit by a portable generator, and the Vagabonds even toted along a newfangled electric player-piano for entertainment.

In addition to this was a team of staff including two chefs, a butler in a white jacket, and a maid to attend the Vagabonds’ wives. “Camp helpers” who set up and ran the campground wore “regulation camp dress—flannel shirts, army breeches, heavy shoes, and puttees.”13

But that was all behind-the-scenes magic. By the time Harding arrived, the Vagabonds had a campground that may have sprung up from the forest floor. Everything ran smoothly. (Aside from a minor incident in which a fire started near a 20-gallon tank of gasoline, which was extinguished by the Secret Service before any of the guests knew about it.)

Reporters eagerly recorded and photographed the campers’ every movement. It was a lively weekend, full of “congenial” activities like “riding horseback, fishing, swapping stories, [and] sharing camp chores together.” As with any camping trip, there was work to be done and fun to be had, odd as it may be to imagine statesmen and commerce magnates knee-deep in river water or battling mosquitoes on hiking trails.

Picture a 74-year-old Edison “[trying] out his agility by swinging himself from a low-hanging branch of a tree.” Henry Ford “unpacked the knives and forks” for dinner, laying out each place at the table. President Harding did his share, too: his job was to chop wood for the kitchen fire.

However, it seemed that Ford was handier with a hatchet than Harding was. “The President tried his hand at the ax, but soon handed it back” to Ford, who finished the job.14

The Vagabonds and their guests (about a dozen in all, not including staff and reporters) ate together under a “big green tent” at a collapsible table that could “be taken apart in three minutes.” To eliminate the need for servers, Ford brought along a massive Lazy Susan so that the words “Pass me the salt” might never be uttered.

“Hey folks,” Ford cried at dinnertime on Saturday. “Come and eat!”

Mrs. Edison didn’t hesitate to correct him on proper camping vernacular: “That’s not the way to say it. You should yell: Come and get it.”15

Harding himself “didn’t have to be called twice” to the table, and for good reason: Saturday’s dinner menu included broiled lamb chops, gridded ham, boiled potatoes, corn on the cob, warm biscuits, watermelon, cake, and coffee.16 Fine china and silver utensils were nowhere to be seen, but cake tastes as good from a tin plate as a porcelain one. Whoever said campers had to go hungry?

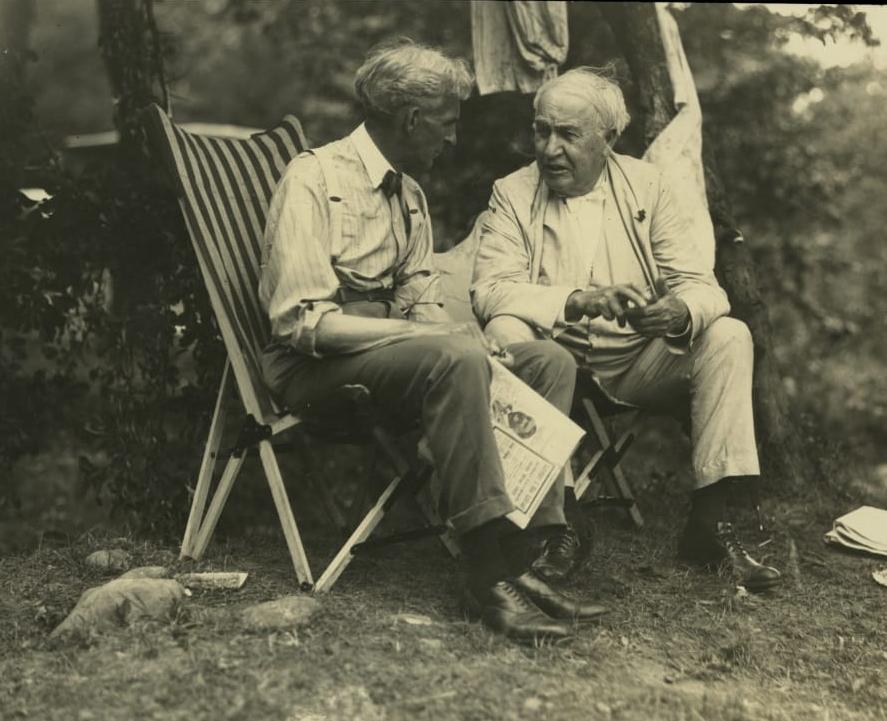

The Vagabonds got along well with Harding, especially Edison, who “of all the members of the camp… appeared to be the favorite.”17 Edison was delighted by the President’s attendance, as was Ford. Both had issues they hoped to discuss privately with Harding. In the isolation of the Maryland mountains, he could monopolize the President’s ear to discuss the crisis in rubber production, and the stubborn refusal of the U.S. military to listen to scientists.

As for Ford, he and Harding disagreed on many issues—immigration, political alignment, the League of Nations. Harding had also joined other government, clergy, and academic leaders in condemning Ford’s well-known antisemitic activities and statements. Before he became President, Harding had been one of many co-signers of a document protesting anti-Semitism in the United States, which was clearly directed at Ford.18 So, the men clearly had their differences. However, both “firmly believed that the obligation of government was to support business, not overregulate it.” Ford had also recently posted a bid on a dam complex and some nitrate plants in Alabama, which he was hoping the President could shunt through Congressional red tape.19

Unfortunately, their schemes amounted to little. Nothing could be discussed in front of the press, who arrived early and did not leave until nightfall, nor could the ladies be present. This left great potential for late-night fireside chats, but Harding barely let anyone get a word in. Firestone wrote that he monologued extensively “about the trials of being president and the vast amount of unnecessary detail imposed upon” him.20

On Sunday, Harding “took his first ride in years.” Firestone had driven six thoroughbred horses down from his Ohio farm for the campers to use. He and Harding were photographed splashing through the narrow creek, and Harding “expressed his enjoyment” at being in a saddle again.21 Earlier that morning there had been more media excitement as the President, Ford, Firestone, and Edison had posed in front of their tents with their shaving razors and lathered faces.

That evening, Harding had to return to Washington. Having “indulged in all camp recreation except fishing” (and produced a good bit of affectionate media coverage), he thanked the Vagabonds for a “most wonderful experience” before setting off on his own motorcade back to the capital and the daily stresses of the presidency.22

The Vagabonds may not have gotten their one-on-one audiences with Harding, but they did receive (mostly) favorable press coverage. As for Harding, it seemed his favorite part of the trip was not the riding, nor the nature, but the food. He got on well with the camp’s chefs, with whom he established favorable “diplomatic relations,” and was rewarded for his efforts with snacks.23

In a letter to Firestone’s aunt, who had helped cater their meals, he wrote: “Any pen would halt in seeking to do justice to cookies, oatmeal, cakes and doughnuts. With a touch (no light one) of superlative good jam they were food fit to make Epicure sorry he did not live at this day.”24

Footnotes

- 1

Lewis, David, Dr. “The Illustrious Vagabonds.” Henry Ford Heritage Association, January 26, 2014.

- 2 Guinn, Jeff. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. Simon & Schuster, 2020. p. 164

- 3 The Glenwood post. (Glenwood Springs, Colo.), 03 Sept. 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 4 Martinsburg journal. [volume] (Martinsburg, W. Va.), 23 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 5 Guinn, Jeff. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. Simon & Schuster, 2020. p. 166

- 6 Martinsburg journal. [volume] (Martinsburg, W. Va.), 23 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 7 Guinn, Jeff. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. Simon & Schuster, 2020. p. 166

- 8 Guinn, Jeff. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. Simon & Schuster, 2020. p. 174

- 9 Jackson County sentinel. (Gainesboro, Tenn.), 08 Sept. 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 10 The Cook County news-herald. [volume] (Grand Marais, Cook County, Minn.), 01 Sept. 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 11 Americus times-recorder. [volume] (Americus, Ga.), 27 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 12 The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 24 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 13 The Cook County news-herald. [volume] (Grand Marais, Cook County, Minn.), 01 Sept. 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 14 The Alaska daily empire. [volume] (Juneau, Alaska), 03 Aug. 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 15 Americus times-recorder. [volume] (Americus, Ga.), 27 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 16 The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 24 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 17 The Tabor independent. [volume] (Tabor, S.D.), 28 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 18

Logsdon, Jonathan R., "Power, Ignorance, and Anti-Semitism: Henry Ford and His War on Jews."

- 19 Guinn, Jeff. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. Simon & Schuster, 2020. p. 165, 168

- 20 Guinn, Jeff. The Vagabonds: The Story of Henry Ford and Thomas Edison’s Ten-Year Road Trip. Simon & Schuster, 2020. p. 177

- 21 Pullman herald. [volume] (Pullman, W.T. [Wash.]), 07 Oct. 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 22 The Tabor independent. [volume] (Tabor, S.D.), 28 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 23 The Washington times. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 24 July 1921. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

- 24

The Raab Collection. “Warren Harding Thomas Edison Letter Signed Caravan Tour,” September 5, 2019.

![Hundreds of draft protestors stand outside the courthouse where the trial of the Catonsville Nine takes place, peace signs up in support of the Nine. (Source: William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0025.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/street-rally-s_0.jpg?itok=E3FhlO92)

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)