Remembering BORF: Washington’s Scruffy, Anti-Establishment Banksy

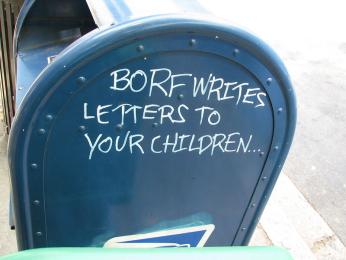

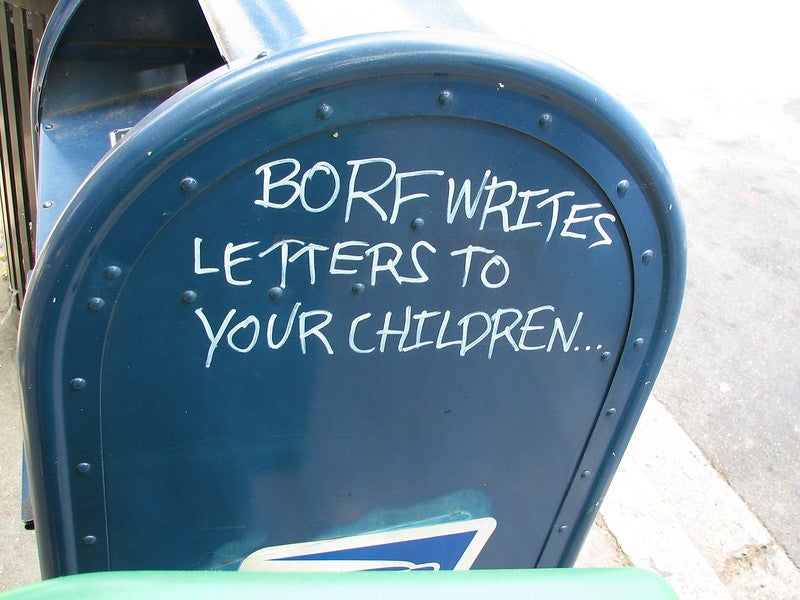

If you were a commuter in Washington around 2004, you might recall a name that began to appear among the spray-painted tags along the metro lines and the stylized graffiti beneath bridges and lesser-traversed side streets. A stencil of a teenage boy pulling a silly face. Bizaare sentences like “Grownups are obsolete” and “Borf writes letters to your children.” Single tags with the name BORF. The unintelligible word was, seemingly and all at once, everywhere.

What was Borf? A person, an ideology, a group? For more than a year, the mystery remained, and the spree of graffiti continued, puzzling residents and commuters alike.

Borf graffiti began cropping up around Washington around early 2004. The pieces were often vague and absurd but had strong elements of anti-authoritarianism and youth empowerment. The goofy grinning face of an unknown teenager, sometimes holding a spray can aloft. Messages decrying the plight of youth under modern capitalism. The cry, “Bush Hates Borf” greeted passengers sliding into the Takoma Metro station.

By 2005, the Borf graffiti was all over Washington: on U Street, in Adams Morgan, West End, Georgetown, and Foggy Bottom. They could be as small as a Sharpie-scribbled name or stencils as large as six feet.1 One of the more daring tags was a fifteen-foot wide BORF above a café on Dupont Circle.

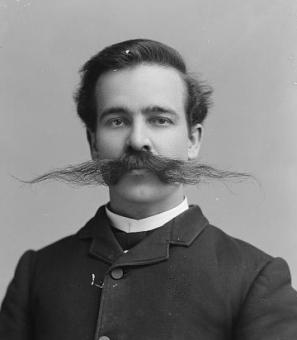

It would eventually be revealed that the man behind Borf—at least originally—was John Tsombikos, an eighteen-year-old art student at George Washington University with “brown hair and brown eyes [and] a solemn, guarded face.”2 He was a peace activist with an anarchist bent. According to a Washington Post reporter who interviewed him on the condition of his anonymity, Tsombikos was guided by “an earnest though sometimes muddled mix of progressive politics filtered through a lens of youthful optimism.” He did not believe in “the state, capitalism, private property, globalization,” or the “selling out” of adulthood.3

The name Borf, Tsombikos revealed, was the nickname of a friend, Bobby Fisher. Fisher and Tsombikos were close: Bobby was mischievous, inattentive, troublesome—and deeply fun. However, his high school years were hard, and mental health issues contributed to his suicide at the age of sixteen in 2003.

Borf’s death deeply affected Tsombikos. It made him distrust the systems in which he lived and disillusioned him with the sagacity and rationality of grown-ups and their world. He also developed an interest in graffiti.

Graffiti was an art form that emerged from “alienation,” from powerlessness. “It’s pretty cathartic to break things, to write on things,” Tsombikos said. “But it’s also to point out that there are huge problems with the place we live in.”4 He took issue with the marginalization of young people, with unfair power structures, with the tyranny of wealth and the personal despair shared by too many of his peers.

In 2005, the BORF tagging spree was a way to honor his friend and resist the system that had driven him to suicide. The Borf name and Bobby’s face “came to stand for all that [Tsombikos] felt was wrong with the world.”5

“That campaign saved me,” Tsombikos told a reporter a decade after the fact.6 It was a rallying cry for other youth, and a call for resistance. Being Borf made him feel “like Batman.”7

Of course, all of Tsombikos’ catharsis was costing the city a lot of money. The DC Department of Public Works was getting calls daily about new tags all through the city. The most audacious work of Borf’s appeared in April 2005. As commuters crossed the Roosevelt Bridge in the morning, they were startled to see that nearly a third of the exit sign for Constitution Avenue was covered with a face that had become grudgingly recognizable: Borf had struck again.

To manage the feat, Tsombikos “had to get onto a catwalk… 20 feet in the air and spray not one but two layers of paint to make a three-dimensional half-face that seemed to have just peeked in front of the sign.”8 He managed to complete the entire thing—and slip away unseen—before the morning rush hour. The mood in Washington was indignant.

But time for Borf was running short. On July 13, 2005, Tsombikos was arrested while tagging a building on the Howard University campus. The city finally knew the identity of the man behind the face that had appeared so bafflingly on their city streets.

Amid the media flurry following his arrest, copycats emerged as awareness and popularity of Borf spiked. At Dupont Circle, young people distributed spray paint and displayed the message: Borf is not caught. Perhaps, as Tsombikos hoped, Borf’s name and face had unified others like him to fight back.

He was sentenced on February 9, 2006, by DC Superior Court Judge Lynn Leibovitz, who was by then very irate with the young man at the defendant’s table. The wave of Borf graffiti, far from being a call to action or act of resistance, was plain delinquency.

“That’s not artistic expression. That is not political expression. That is not grief therapy. That is vandalism,” she admonished from her bench. “Washington, D.C. is not a playground that was built for your self-expression.”9

Besides community service and a $12,000 fine, Leibovitz sentenced Tsombikos to thirty days behind bars, unusual for a young first-time offender convicted only of a property crime charge. His mother pleaded for probation or time in a halfway house, but Judge Leibovitz seemed to think Tsombikos needed a strong reality check—not least because he had been arrested again in the interim for defacing a streetlight box in Manhattan.

“I want him to see what the inside of a D.C. jail looks like,” she said. “Unlike every other person you've seen in my courtroom this morning, who have a ninth-grade education, who are drug-addicted, who have had childhoods the likes of which you could not conceive, you come from privilege and opportunity and seem to think that the whole world is just like McLean [Gardens].”10

In addition to spending thirty days in jail (an experience which soured him on the city), Tsombikos was ordered to stay out of Washington except for classes at GWU.

But just as Tsombikos hoped, his exile from D.C. did not immediately quash Borf. A group of young people, supporters of Tsombikos’ philosophy and modus operandi, took up the name and symbol of Borf for themselves. This new Borf Brigade told the DCist that though the police had claimed to have apprehended the young man behind the moniker, “there is no one Borf.”11 Tsombikos said the name had always belonged to Bobby; the Brigade’s mission was to “pick up the carpet that They swept him under.”12

Several months after Tsombikos’ sentencing, the Borf Brigade released a communique addressing the citizens of DC. It dismissed the “hullaballoo” around the arrest of John Tsombikos, whom they declared only a “minor Borfist.”13

They railed against societal problems contributing to the worthlessness and despair that led to suicides of young people like Bobby Fisher. Among them were curfews, and authorities who “would rather profit off of our misery… than spend a dime on programs that empower youth and give us the tools to think independently.”14

The Borf Brigade announced Operation Twist & Shout, their resistance, armed with pens, against a “paralyzing and debilitating” culture. According to the communique:

“For every rush hour Metro delay, dropped cell phone call, jammed coin return, mysterious odor, Borf will be involved. We will reface every wall, rhyme on every stall and have the gall to have a blast.”

Perhaps the Borf Brigade intended a declaration of war. Nothing much ever came of the campaign. Regardless of any minor inconveniences or property damage possibly attributable to the Borf Brigade, there were no arrests that roused the same media frenzy as Tsombikos’ in 2005.

There was also the Bobby Fisher Memorial Building, an abandoned warehouse occupied by the Brigade in partnership with Tsombikos for several years. Originally an “autonomous zone to promote civil disobedience [and] urban pranksterism,” it was a sort of addendum to the Borf mission.15 It was in this building that Tsombikos staged a 2007 art show intended to raise funds for his $12,000 fine owed to the city.

The building closed in 2008 after a rent agreement with the landlord fell apart. Its last exhibition was Girlish Ways, featuring feminist art installations from twelve female artists. With the closing of Bobby Fisher, the last physical foothold of Borf in Washington fell away.

Today, John Tsombikos has mostly left the Borf moniker behind, continuing to make art in New York. But he remains committed to his anti-adult, anti-authority philosophy. Even in 2015, he was unwilling to tell a reporter that he had grown up.

“What does growing up mean?” he asked her. “Compromising my principles?”16

Footnotes

- 1

Copeland, Libby. “The Mark Of Borf.” The Washington Post, July 14, 2005. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/13/AR2005071302448.html.

- 2

Manteuffel, Rachel. “10 Years after His Graffiti Campaign, the Artist Known as Borf Paints a New Life.” The Washington Post, August 10, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/borf-10-years-later/2015/08/10/07f9080c-3155-11e5-8f36-18d1d501920d_story.html.

- 3

Copeland, Libby.

- 4

Dissonance. “5-15-07 BORF!” RadioCPR, May 15, 2007. https://dissonance.libsyn.com/5_15_07_borf_.

- 5

Copeland, Libby.

- 6

Manteuffel, Rachel. “10 Years after His Graffiti Campaign, the Artist Known as Borf Paints a New Life.” The Washington Post, August 10, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/borf-10-years-later/2015/08/10/07f9080c-3155-11e5-8f36-18d1d501920d_story.html.

- 7

Copeland, Libby.

- 8

Copeland, Libby.

- 9

Cauvin, Henri. “Borf Gets Month in Jail And Rebuke for Graffiti.” The Washington Post, February 10, 2006. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/02/09/AR2006020902273.html.

- 10

Cauvin, Henri.

- 11

CatherineA. “DCist: A Borf-In at Dupont Circle.” The DCist, July 24, 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20061019085916/http:/www.dcist.com/archives/2005/07/24/a_borf-in_at_du.php.

- 12

Dissonance.

- 13

Visual Resistance. “Borf Brigade Communique,” August 14, 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20080406140039/http:/visualresistance.org/wordpress/2006/08/14/borf-brigade-communique/

- 14

Visual Resistance. “Borf Brigade Communique,” August 14, 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20080406140039/http:/visualresistance.org/wordpress/2006/08/14/borf-brigade-communique/.

- 15

Capps, Kristen. “DCist: The House That Borf Built Is Closing.” DCist, June 26, 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20081102213533/http:/dcist.com/2008/06/26/the_house_that_borf_built_is_closin.php.

- 16

Manteuffel, Rachel. “10 Years after His Graffiti Campaign, the Artist Known as Borf Paints a New Life.” The Washington Post, August 10, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/magazine/borf-10-years-later/2015/08/10/07f9080c-3155-11e5-8f36-18d1d501920d_story.html.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)