“A Great City to Be”: Architect Leon Krier’s Plan to “Finish” Washington D.C.

Washington, D.C. undoubtably stands as one of America’s most iconic cities. New York has its cosmopolitan skyscrapers, Chicago its streamlined Art Deco silhouette, and San Francisco is recognizable by its bay windows and old streetcar tracks. But among America’s urban centers, Washington stands alone with its classical architecture, hefty monumental core, and unmistakable (rigidly regulated) low skyline. In 2007, a poll found that six of Americans’ ten favorite buildings were in D.C.1 Architectural wonders like the Library of Congress, White House, and Smithsonian Castle are known the world over.

European architect and theorist Leon Krier, however, saw the construction of Washington quite differently. In 1985, he made his debut in the American consciousness with an audacious plan to correct the errors in L’Enfant’s city.

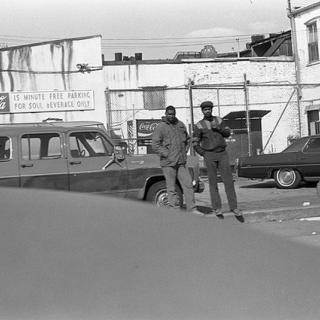

Born in post-war Luxembourg, Krier had first visited Washington in 1975, expecting to find “a place of beauty and privilege and elegance” befitting the capital of the free world. Instead, he found “slums” three blocks away from the White House. The contrast between the “fantastic” Classical buildings and the “incomplete” parts of the city fascinated him.2

He returned to Europe thinking about how America’s ideals of freedom, enterprise, and opportunity might be truly expressed in its capital city. To him, Washington was a jewel stuck deep in mud. It was “a great city to be, a grand skeleton with noble limbs but little flesh.”3

In 1985, the Museum of Modern Art invited Krier to participate in an exhibit series on young thinkers in architecture. He was invited to design a piece for New York City, but Krier instead chose to redesign a place more interesting to him: the American capital.

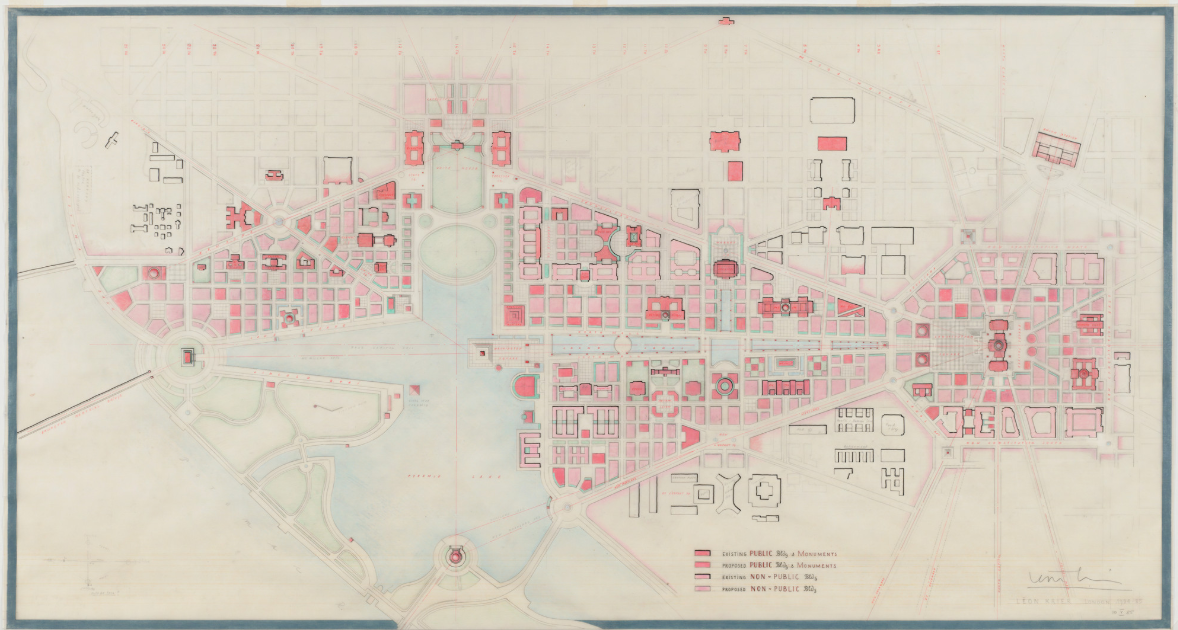

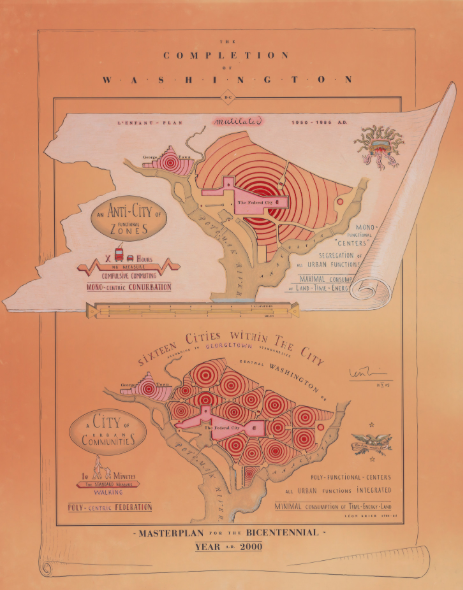

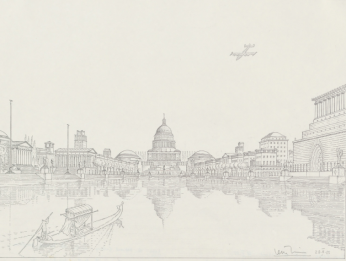

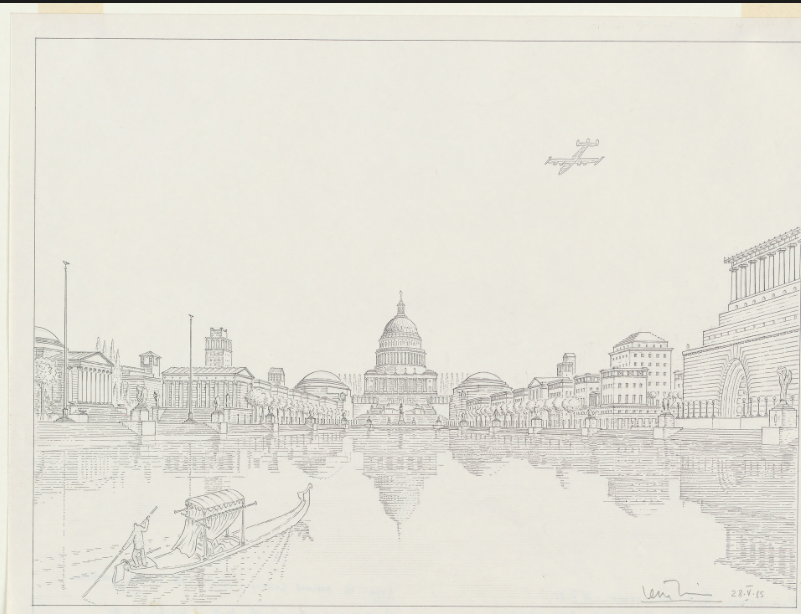

He presented the MoMA with his exhibit piece, called “The Completion of Washington, D.C., A Bicentennial Masterplan for the Federal City.” It expanded the neoclassical aesthetic of Washington’s monuments to the entire city, made it denser and more compact—and blasted an artificial lake into the center of the National Mall.

Even before his 1985 “Masterplan,” Leon Krier had developed a reputation as a self-satisfied pariah among his architectural peers. He dropped out of architecture school after presenting only Classical designs to his “bemused” professors (all staunch Modernists), who refused to award him a grade.4 He continued his trajectory “outside the mainstream” by publishing on Albert Speer, Hitler’s minister of Armaments and designer of the Reich Chancellery and Nazi rally grounds at Nuremburg.5 Krier would suggest that America would have done better after World War II to forego Werner von Braun (Hitler’s rocket engineer and later designer of Apollo spacecraft) and instead adopt Speer.

For what purpose should Americans have hired the Nazi architect? Krier answered: “To replan Washington, D.C.”6

A note: Krier’s interest in Speer was more about devotion to classical architecture than ideology. Criticism or praise of Speer’s architectural output was not necessarily inextricable from Naziism. In Krier's view, totalitarianism is far more modernist than classical. However, for most critics, Krier stopped too short of fully condemning Speer’s artistic production in service of the Nazis. On the subject, Krier has said: “Can a war criminal be a great artist? My answer is clearly yes.”7

Krier developed a resoundingly anti-Modernist architectural philosophy. The “downtown, suburb, and strip model” of urban development was a “tragedy” for “urban culture.”8 He ruffled feathers when he declared that Modernism had corrupted a whole generation’s sense of beauty. Young people, he complained, “consider a classical column more dangerous than a nuclear power station.”9

As the theorist, Krier was a supporter of vernacular, or popular, architecture, and a return to Classical styles. He insisted on “the organic wholeness” of a city and argued that a city was made of urban quarters of self-contained communities. Instead of building single-use zones (e.g., a commercial downtown, residential neighborhoods, an arts district), responsible urban planners created polyfunctional blocks and multi-use neighborhoods. Krier built his cities without cars or even public transit: in his ideal world, any resident would be able to walk to their destination.

In his book, The Architecture of Community, Krier outlined his theoretical characteristics of his ideal urban quarter. The “pedestrian must have access” to all weekly needs (home, work, education, shopping, public services, leisure, etc.) “within ten minutes’ walking distance.”10 A quarter would hold no more than 10,000 people, organized in streets and squares. The center of the quarter should be dense and closely packed to create “a feeling of centrality,” and its borders formed by parkways, public gardens, and wide avenues.11 Cul-de-sacs, symbols of stagnant and isolating suburbia, were to be avoided at all costs.

These were the tenets by which Krier sought to “finish” America’s capital, which should have stood as a “model” for cities the world over. Instead, American cultural dominance had spread “the worst of its inventions,” namely “suburbia and cheap, vulgar commercialism,” in D.C. and beyond.12

He would fix that by reshaping Washington into a neoclassical dreamscape of broad avenues, pedestrian streets, public gardens, and covered gondolas. He eradicated parking lots and commuter services. The city would look like modern antiquity, nucleated and community oriented. “The center core” of Washington, Krier stated, was “an empty canvas which need[ed] to be repainted.”13

Leon Krier took to his canvas with broad and vibrant brushstrokes, and the Masterplan was his product.

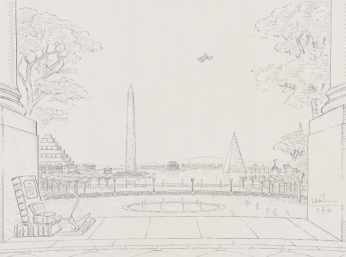

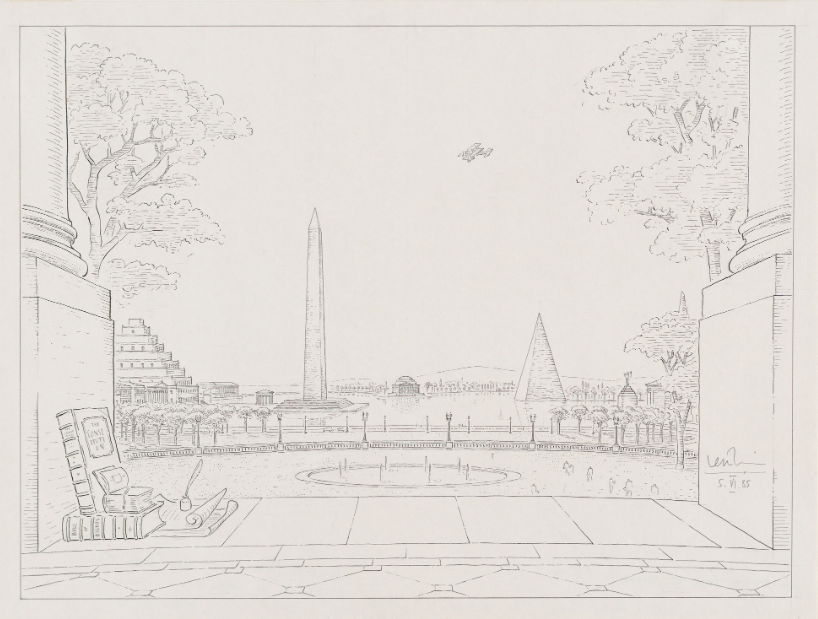

The most eye-catching part of the plan was Krier’s intention to flood the Tidal Basin and much of the National Mall, anchoring the Federal City around a massive artificial lake down which gondolas and rowboats could sail. He would gradually broaden the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool into the lake to “intensify the perspective” of the monument.14 Modernist buildings like the Hirshorn would be “obscure[d]” by more pleasing classical structures.15

Krier’s plan dealt only with the center of Washington between New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland Avenues, and the Potomac River. This area was divided into four “towns” which obeyed Krier’s philosophy for a functional, utilitarian cityscape. It would be called the “Federal City” and would form one of sixteen urban communities within Washington following Krier’s urban and architectural philosophy.

Within the Federal City were four towns: Capitol Town (around the Capitol), Washington and Jefferson Towns (along the north and south sides of the Mall before the Washington Monument), the White House, and Lincoln Town (south of Foggy Bottom). Altogether, Federal City would house up to 80,000 citizens, almost all of whom would work locally—no more commuting.

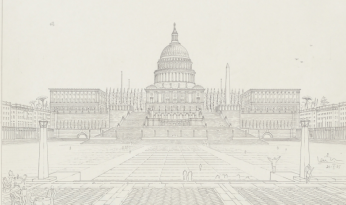

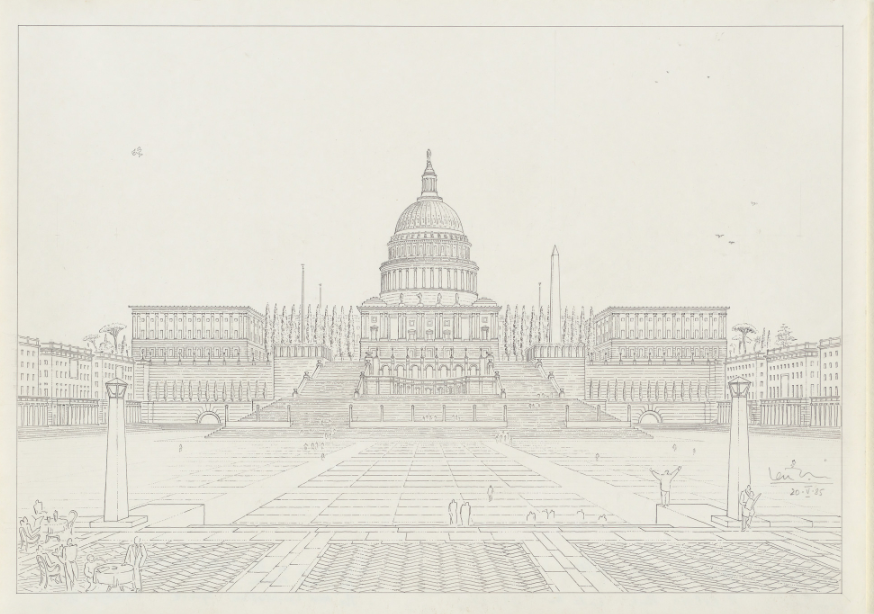

Capitol Town would be the largest division. Krier intended to house 20-30,000 people by constructing new apartment buildings, each three to four stories tall. This required filling in the Capitol lawn with two new streets, and surrounding the Library of Congress and Supreme Court, too. Krier envisioned that the “intimate squares” created by this construction would “increase [the] monumentality” of the public buildings.16

To make the Capitol less unsightly, he would rip up Frederick Olmstead’s grounds and excavate the east end of Capitol Hill to create a square massive enough to hold 200,000 spectators on Inauguration Day—the demolition of the Grant Memorial would be a small price to pay. He would also plant lines of cypress trees between the rotunda and each chamber of Congress. This, Krier said, would improve the view of the Capitol’s west façade, which is currently “a shapeless lump with its cupula floating like a dish on too broad a tabletop.”17

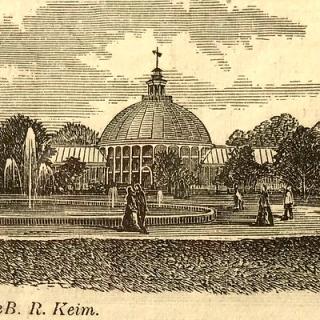

Washington and Jefferson Towns would require the most construction work. Krier saw no alternative but to rip everything up and rebuild with “tower-like pavilions,” “hanging gardens” and “tree-lined canals” to improve the aesthetics of the neighborhoods.18 He would slim the Mall down to match the contours of Constitution Avenue and fill it with utilitarian but beautiful buildings. The Federal Triangle, currently a wasteful desert of neoclassical bureaucratic buildings, would be transformed into a “tight network of streets and squares.”19 Krier also envisioned the demolition of the “unsightly” Museum of American History.20 It would be rebuilt as a stepped pyramid on the shores of the overflowed Tidal Basin lake, where the current Museum of African American History sits.

Krier appreciated the architecture and aesthetics of the White House, which got its own section in his plan. But its current environment needed tidying: Western Plaza made the terminus of Pennsylvania Avenue “awkward,” and the President’s residence itself was “dwarfed by oversized… complexes” like the Department of Commerce.21 To correct this mistake, Krier would excavate the White House’s surroundings and fill them with shorter buildings and plazas “to reestablish the White House in its symbolic prominence.”22 Fitting with Krier’s plan for the Tidal Basin, the Ellipse was redesigned into a massive fountain.

Lastly, Lincoln Town—in the underpopulated surroundings of the Lincoln Memorial—would mimic the “atmosphere of an elegant resort town.”23 Probably with much glee, Krier envisioned toppling several modernist office buildings which were “functional and political anachronisms,” replacing them with apartments, shops, and public services.24 Though Krier left the Supreme Court where it was, he implied that the opposite end of the Mall would be a more ideal location for America’s seat of justice. Its current position on First Street made it “an unequal pendant to the Library of Congress” and “a mere annex to the Capitol” hardly fit for the equal and independent branch of the Judiciary.25

The MoMA’s press release for Krier’s portion of the exhibition described his Masterplan as “repudiat[ing] modern technology” and presenting “the most compelling alternatives yet seen to modern and postmodern architecture.”26 Journalists’ reactions to the plan were more mixed.

The New York Times called Krier a “polemicist and a moralist” who despised Modernism as an “esthetic… social and technological” failure.27 A Washington Post reporter aptly characterized the plan as “beautiful yet appalling, magnificent but megalomaniacal, pragmatic though preposterously impractical."28

However, many observers also appreciated the appeal of the Masterplan, even if it had landed with an air of Old World superiority. Krier’s design revived “essential qualities” of the capital which had been “diminished by the relentless suburbanization of the city.”29 It would make life simpler and calmer, allowing people to live where they worked in neighborhoods emphasizing comfort and beauty. He was the only one proposing any alternative to the “massive single-use office district” that downtown Washington had become.30

Of course, the Masterplan was never meant to be realized. Krier was an architect who preferred to design and deigned to build. The Masterplan was an expression of theory, a proof-of-concept for Krier’s anti-modernist, anti-consumerist, and anti-suburbia philosophy. If it impressed the public, it was only as a novelty—an interesting hypothetical.

Even if there had been an outpouring of support to bulldoze central D.C., Krier was “blissfully carefree about costs.”31 Though most of Washington’s public buildings and monuments remained where they were (apart from the Museum of American History), his plan still would have required entirely new streets, office buildings, apartment blocks, and storefronts to be erected, some of it on public land.

Krier’s plan may have been a pipe dream par excellence, but he has continued to be vocal about the trajectory of Washington’s architecture. In 2012, he wrote a scathing indictment of Frank Gehry’s planned Eisenhower Memorial on Independence Avenue. Though Gehry was Krier’s friend and colleague, he held back no criticism of the postmodern memorial: “The scale and character of the blotted tagged fence relates more to highway billboards and graffiti than to the historic tapestry it declaredly refers to.”32

Ever an advocate of the neoclassical and grandiose, Krier’s solution to the Eisenhower Memorial was not much different from the Masterplan he had presented three decades earlier. The $112.5 million of public money allocated to this “oversized forecourt” would be more efficiently and morally used on “a fine classical building.”33

Footnotes

- 1

American Institute of Architects, "About this Exhibit", Favorite Architecture.org, May 10, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110510113118/http://favoritearchitecture.org/afa150.php

- 2

Classic Planning Institute. “Léon Krier - Completing the Plan of Washington D.C.,” April 22, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAPabA-zl64.

- 3

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 4

Pawley, Martin. 20th Century Architecture: A Reader’s Guide. Architectual Press, 2000. pp. 92-95

- 5

Pawley, Martin. 20th Century Architecture: A Reader’s Guide. Architectual Press, 2000. pp. 92-95

- 6

Pawley, Martin. 20th Century Architecture: A Reader’s Guide. Architectual Press, 2000. pp. 92-95

- 7

Moore, Rowan. “Is Far-Right Ideology Twisting the Concept of ‘heritage’ in German Architecture?” The Guardian, October 6, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/06/a-dubious-history-in-the-remaking-germany.

- 8

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 9

Pawley, Martin. 20th Century Architecture: A Reader’s Guide. Architectual Press, 2000. pp. 92-95

- 10

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 11

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 12

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 13

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 14

Goldberger, Paul. “Architecture View; Embracing Classicism in Different Ways.” The New York Times, June 30, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/30/arts/architecture-view-embracing-classicism-in-different-ways.html?searchResultPosition=5.

- 15

Goldberger, Paul. “Architecture View; Embracing Classicism in Different Ways.” The New York Times, June 30, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/30/arts/architecture-view-embracing-classicism-in-different-ways.html?searchResultPosition=5.

- 16

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 17

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 18

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 19

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 20

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 21

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 22

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 23

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 24

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 25

Krier, Leon. The Architecture of Community. Island Press, 2009. https://archive.org/details/architectureofco0000krie/page/204/mode/1up?view=theater&q=washington.

- 26

Museum of Modern Art. “Ricardo Bofill and Leon Krier: Architecture, Urbanism, and History.” Press Release, May 1985. The Museum of Modern Art, 1985. https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_press-release_327405.pdf

- 27

Goldberger, Paul. “Architecture View; Embracing Classicism in Different Ways.” The New York Times, June 30, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/30/arts/architecture-view-embracing-classicism-in-different-ways.html?searchResultPosition=5.

- 28

Forgey, Benjamin. “Cityscape.” The Washington Post, July 6, 1985. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1985/07/06/cityscape/18373552-85a3-413e-b679-7507dcf4a4cc/.

- 29

Goldberger, Paul. “Architecture View; Embracing Classicism in Different Ways.” The New York Times, June 30, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/06/30/arts/architecture-view-embracing-classicism-in-different-ways.html?searchResultPosition=5.

- 30

Forgey, Benjamin. “Cityscape.” The Washington Post, July 6, 1985. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1985/07/06/cityscape/18373552-85a3-413e-b679-7507dcf4a4cc/.

- 31

Forgey, Benjamin. “Cityscape.” The Washington Post, July 6, 1985. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1985/07/06/cityscape/18373552-85a3-413e-b679-7507dcf4a4cc/.

- 32

Krier, Leon. “Krier: Gehry’s Eisenhower Memorial Is an ‘Anti-Monument.’” Metropolis Magazine, February 14, 2012. https://metropolismag.com/projects/krier-gehry-eisenhower-memorial-anti-monument/https://metropolismag.com/projects/krier-gehry-eisenhower-memorial-anti-monument/.

- 33

Krier, Leon. “Krier: Gehry’s Eisenhower Memorial Is an ‘Anti-Monument.’” Metropolis Magazine, February 14, 2012. https://metropolismag.com/projects/krier-gehry-eisenhower-memorial-anti-monument/https://metropolismag.com/projects/krier-gehry-eisenhower-memorial-anti-monument/.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)