The Man in the Green Hat: Congress' Bootlegger During Prohibition

The 18th amendment was ratified on January 16, 1919, while George Cassiday was serving in France with the 321st Light Tanks in World War I. U.S. troops received cognac in their rations, and on the ship home from Europe in 1919, the 2,200 men on board with Cassiday “took a straw vote on prohibition just before the ship docked in New York. All but 98 of the men aboard voted against it.”[1]

Upon his return from the war, Cassiday failed the physical exam to return to his job as a brakeman and flagman for the Pennsylvania Railroad and became among the 40% of WWI veterans who were unemployed.[2] In the summer of 1920, a friend suggested a new line of work in Washington, D.C.[3]

Just months before — on January 17, 1920 — Prohibition became the law of the land. But by that time, the District had been dry for over two years. The Sheppard Act, which went into effect on November 1, 1917, outlawed the sale of alcohol in the nation’s capital.[4] In effect, D.C. was intended to be the “model dry city,” but it didn’t exactly work out that way.[5]

“It may be a surprise and a shock to many good people to know that liquor has been ordered, delivered, and consumed right under the shadow of the Capitol dome ever since prohibition went into effect,”[6] Cassiday recalled later. Indeed, elected officials, some of whom voted in support of the 18th amendment and publicly supported Prohibition, drank a lot of alcohol in the 1920s.

The purveyor of much of that alcohol? George Cassiday.

The career shift from railroad brakeman to Congressional bootlegger may have been a bit of a surprise to those who knew Cassiday. He didn’t grow up around alcohol. His mother was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and his “father did not take a drink for 32 years before his death and having had this example of sobriety held up to me as a youngster I have never been a regular drinker,”[7] Cassiday wrote in 1930.

However, he wasn’t one to pass up an opportunity and bootlegging was just that.

“In the summer of 1920, I met this friend in the lobby of the old Hotel Varnum in Washington,” Cassiday wrote. “He introduced me to two representatives from a Southern State. They asked if I could supply them. After making arrangements to get the stuff, I made my first deliveries on Capitol Hill to these two members. These were the first members of Congress I had ever met.” Cassiday later learned that his first customers both voted in favor of the 18th amendment.[8]

His operation started out small, but Cassiday soon “had the run of the Senate and House Office Buildings and was spending more time there than most of the representatives.”[9] His original customers began to introduce him to their colleagues and the new members, and soon, they were giving him suggestions about how to improve his growing business.[10]

“One day a congressman from a Middle West State said to me: ‘George, did it ever occur to you it would be easier to bring supplies into the building in larger lots and distribute it from a base of operations from the inside?’ It was then I began storing and cutting liquor for the use of members of Congress in the House Office Building itself.”[11]

One of those customers provided a key “to a room in the House Office Building where I could stow a good quantity away out of sight.” The room had windows and a door, but Cassiday could bolt the door and close the blinds when he was inside. He and his customers developed a “special knock” that everyone had to use before he would open the door.[12]

With the security in place at the Capitol today it may be hard to imagine that during the 1920s, the Capitol Police only inspected packages people carried out of the building. Staffers could bring bags in without being searched.[13]

To supply his office stock, Cassiday found it was easiest to fill suitcases with alcohol and bring them into the Capitol late in the day when a lot of people were coming and going, or at night. “The fact that the Capitol police and the door guards were appointed by members of Congress seemed to assure me protection in getting into the building,”[14] he recalled.

On an average day, he would run between all 16 corridors in the House Office Building to deliver 20 to 25 orders. On his busiest day, he made 47 deliveries. “Members from a good majority of the States” purchased alcohol from Cassiday at some point during their tenure in Washington.[15]

As the only member of his one-man operation, Cassiday was also responsible for managing his supplies. He would take the train from Union Station to suppliers along the east coast to keep up with the increasing demand.[16] The trips presented some inherent risk, as he recalled later.

“Late one afternoon I set a suit case down too hard in the waiting room. As I was walking across the concourse of the station to the train a passer-by grinned and called out to me: ‘Say, Buddy, your clothes are leaking.’ There was nothing to do but go on through and I made the train as quickly as I could. When I got aboard I went into the rest room and threw out the broken bottles. Most of the bottles were intact and were delivered in good order to customers on Capitol Hill.”[17]

In his spare time, Cassiday would sometimes sit in the gallery and listen to floor speeches and debates. “Being a former service man I naturally was interested in the soldiers’ bonus legislation and other bills for care and compensation for veterans, and I followed them closely.”[18]

The bootlegger also paid attention to discussions about Prohibition, and he noted the hypocrisy of his customers’ public comments in comparison with their actions.

“I have heard members of the House and Senate making strong arguments on the floor that prohibition was being well enforced when I knew good stuff was being regularly delivered at their own offices for use by their secretaries or clerks.”[19]

Cassiday knew that alcohol consumption in the Capitol wasn’t limited to the secretaries and clerks. In fact, he sometimes drank with his customers.

“It wasn’t a question of buyer and seller at these gatherings, but we all just enjoyed ourselves together. We would have a few rounds of drinks, sing a few songs, and have a general good time.”[20]

Business was humming along until 1925. Around that time, a “so-called vice-committee,” made up of “dry” Congressmen Thomas Blanton,[21] William Upshaw,[22] John Cooper,[23] and Louis Cramton[24] became active — a group Cassiday points to as possibly having initiated the following series of events:[25]

One morning, Cassiday came into the building with alcohol in his briefcase, and he walked past a guard he’d passed “hundreds of times” before. The guard told Cassiday the lieutenant wanted to see him. Cassiday continued about his business, stopping by a representative’s office, with the guard following him. “He had no evidence whatever that I was carrying alcohol.” Cassiday tried to leave his briefcase in the office, but the guard took it to the guard room. “There he swore out a warrant, something that has been overlooked while he was molesting me.”[26]

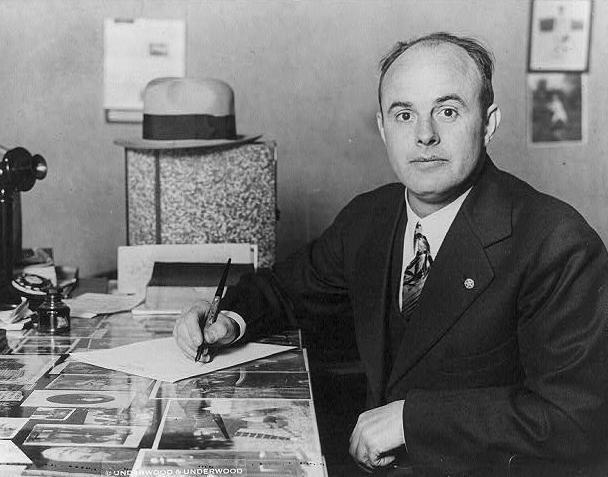

On the day he was arrested, Cassiday was wearing a “light green felt hat,” which earned him a nickname that would stick with him for years to come.[27] His arrest and the charges against him were reported in a brief, three paragraph write-up on page 22 of The Washington Post. The article explains that Cassiday was caught with alcohol in the House Office Building, but makes no mention of the fact that he was selling it to Congressmen.[28]

“The Man in the Green Hat,” as Cassiday came to be known in the press, pled guilty to charges of alcohol possession and he said the judge gave him the limit — a 90-day sentence in a District jail. The customer he was delivering to did not face any punishment and is still anonymous. Cassiday never publicly revealed much about his time in jail, other than to say, “while in the District Jail I was detailed to the drug room and did the same work Harry Sinclair later performed in the same institution as a doctor’s orderly.”[29]

In the aftermath of the arrest, Speaker of the House Nicholas Longworth, an Ohio Republican, made a special rule barring Cassiday from the House Office Building.[30] Longworth, whose family was in the winemaking business,[31] was one of 128 members of the House who voted against the 18th amendment.[32] Since Cassiday never revealed his customers’ identities, we’ll never know if Longworth was one of them.

Following his run-in with the law, there didn’t seem to be much stopping Cassiday from resuming his operation on the other side of the building. Upon his release from jail, the Man in the Green Hat returned to Capitol Hill with his suitcases full of booze. “I moved over to the Senate Office Building after being barred from the House side in 1925,” he recalled.[33] The fact that a convicted bootlegger was able to resume his work in the halls of Congress so easily speaks volumes about how Prohibition was viewed and inconsistently enforced – even by those making the laws of the land.

As he recalled in 1930, “So far as I can tell from experience on both the House and Senate sides, there has been little change in enforcement conditions in Washington during the last 10 years.”[34]

In the House, Cassiday often dealt directly with his customers, but senators tended to be more discreet, placing orders through their secretaries. Members from both houses “would take a lot of pains to work up a little system for giving orders and getting them filled and seemed to enjoy watching it operate."[35]

One senator stored his alcohol “on the top shelf of a bookcase in his private study which was reserved for bound volumes for the Congressional Record.” This person called Cassiday “his librarian” and would tell Cassiday he needed “some ‘new reading matter.’” Cassiday would come in, deliver the alcohol, and rearrange the Congressional Record on the bookshelf.[36]

By the holiday season of 1929, Prohibition wasn’t over, but Cassiday’s bootlegging career was about to end. A “dry spy” had been planted in the Senate stationery office as a temporary worker during the 1929 holiday rush. The spy, 20-year-old Roger Butts, spent a while trying to establish a relationship with Cassiday and buy alcohol from him, but Butts said Cassiday was initially suspicious of him.[37]

Later, Butts “secured the cooperation of another Senate employee who knew Cassiday well and he and I fixed up a plan that I should come into the stationery room apparently drunk. The idea was to have this get back to Cassiday so he would believe I was in the habit of drinking,” Butts recalled.[38] Cassiday, however, remained wary and avoided making any direct sales to Butts.

After several months on the job, Butts worked with the Prohibition Bureau to come up with a plan to trap Cassiday. Butts got another Senate building staffer to place an order for six fifths of gin to be delivered “in the space back of the Senate Office Building,” at 11 a.m. on February 18, 1930. Cassiday took the bait and two Prohibition Bureau agents readied to arrest “The Man in the Green Hat.”[39]

As Butts recalled later, “Cassiday had been smart enough not to bring the liquor in his own car but the agents found the six fifths of gin in another automobile driven by another man for whom Cassiday was acting as sort of a convoy...While the agents found no liquor either on Cassiday’s person or in his car they did find a little black book in his inside coat pocket which contained the names and office numbers of the senators, congressmen and their secretaries.”[40]

The contents of the little black book never became public, despite requests by some who wanted to clear their names.[41] In one of the enduring mysteries of The Man in the Green Hat, even Cassiday’s son, Frederick, doesn’t know what happened to the book. At one point, he surmised in a 2011 interview with WETA, copies of the book may have been made, but believes they were subsequently destroyed.[42]

George Cassiday faced charges of transporting and possessing liquor, both of which he was found guilty of on July 16, 1930. Cassiday’s lawyers “made no attempt to defend their client on the charge of possession” but did try to argue that moving his car just a few feet did not justify a transporting charge.[43] The jury decided otherwise.

Cassiday was sentenced to jail time, but he never actually spent the night in jail. According to his son, Cassiday reported to the jail each morning and signed himself in. At the end of the day, he signed back out and went home.[44]

That fall, Cassiday shared his story with the world. “He’s the only bootlegger that I know of who spills the beans,” remarked Garrett Peck, author of Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t. “And he did it in incredible style. Five front-page articles in The Washington Post.”[45]

From October 24–28, 1930, The Post ran a tell-all series of articles penned by Cassiday where he told the world about his operation. Though he didn’t name names, it was hard to ignore the hypocrisy that so many lawmakers had exhibited when it came to drinking. He estimated that he supplied alcohol to 80% of the senators and representatives working in the Capitol during Prohibition.

The final piece of Cassiday’s series was published just one week before the 1930 mid-term elections. It’s hard to judge exactly how much impact Cassiday’s articles had, but they attracted national attention, and are credited with helping “wet” Democrats regain control of Congress.[46]

As a follow up, Butts wrote his own series of four articles, which detailed Cassiday’s arrest for The Post in November 1930. For the young spy, it was the beginning of a life of undercover work. He would go on to work for the CIA and was responsible for relaying coded messages during the Bay of Pigs Invasion.[47]

For Cassiday, the hypocrisy was understandable. “You can’t blame these men for taking the same means of refreshment and relaxation other people enjoy,” he wrote in the final installment of his Post series. “Some of the senators and congressmen are hard workers who are busy from morning to night in committees or on the floor. When a day’s session is over, it is only natural for half a dozen of them to gather in one of the offices and enjoy a sociable round of drinks.”[48]

As it turned out, that sort of behavior was happening all over the country. Many hard working Americans — who were deep into the throes of the Great Depression by the early 1930s — were losing patience with Prohibition (if they ever had any to begin with) and finding ways to drink.

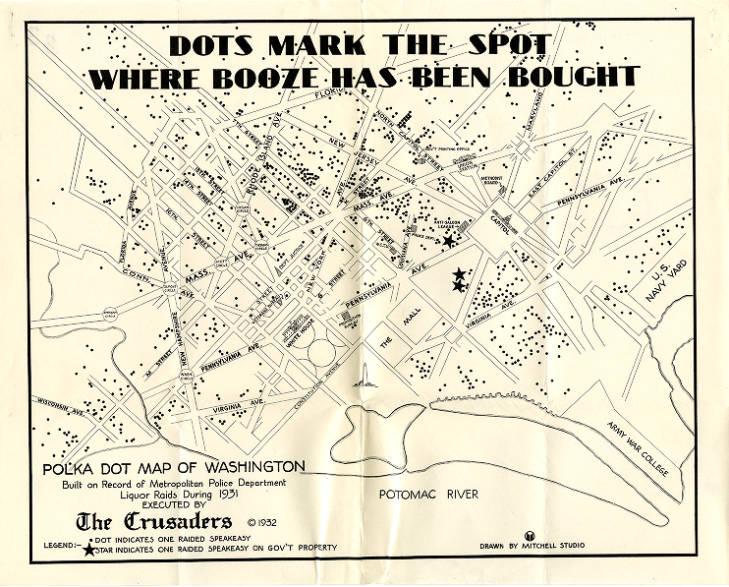

Case in point: In 1931, The Crusaders, a group in favor of repealing Prohibition, published a map showing the locations of 1,155 speakeasies in the District that had been raided and were found to have alcohol. Some locations on their map were government offices.[49] So much for D.C. being the “model city for Prohibition.”

Finally, on December 5, 1933, “the 13 awful years” came to an end when the 21st amendment was ratified.[50] Prohibition ended in all 50 states. Locally, Marylanders and Virginians could pop bottles legally that holiday season, though D.C.’s unique status meant District residents had to wait a few more months until March 1, 1934 for alcohol to become legal again.

So whatever happened to The Man in the Green Hat? By the mid-1930s, George Cassiday left the national spotlight and returned to a normal life. His bootlegging career had given him a job when he needed one, but Cassiday said he just made enough money to support his family during those 10 years, not become rich. He worked at a shoe factory in Pennsylvania and at some hotels in D.C. before his death in 1967.[51]

In 2012, D.C.-based New Columbia Distillers released “Green Hat Gin” in Cassiday’s honor.[52] Had he been around to sample it, the old bootlegger might have gotten a kick out of the honor though, according to his son, Cassiday was not really a hard liquor guy. His preferred drink was Yuengling beer.[53]

Footnotes

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.,” The Washington Post, October 24, 1930.

- ^ Ryan Reft, “Veterans Day: Struggling to Build a New Life after War | Library of Congress Blog,” Loc.gov, November 9, 2017, https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2017/11/veterans-day-struggling-to-build-a-ne….

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.”

- ^ “Sustains ‘Dry’ Law,” The Washington Post, October 25, 1917.

- ^ “Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t,” Library of Congress, October 26, 2011, https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-5331.

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday, Capitol Bootlegger, Got First Rum Order from Dry: Former A.E.F. Veteran Had Entree to Many Offices. Solid State Delegation of Dozen Members Once on List.”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Part of Cassiday’s Rum Supply Stores in House Office Building,” The Washington Post, October 25, 1930.

- ^ George Cassiday, “Part of Cassiday’s Rum Supply Stores in House Office Building”

- ^ “Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t,” Library of Congress

- ^ George Cassiday, “Part of Cassiday’s Rum Supply Stores in House Office Building”

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday,” The Washington Post, October 26, 1930.

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday Reveals Rum Dealings in U.S. Senate Office Building”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday Reveals Rum Dealings in U.S. Senate Office Building”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday Reveals Rum Dealings in U.S. Senate Office Building”

- ^ “Unprohibited | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives,” history.house.gov, October 11, 2016, https://history.house.gov/Blog/2016/October/10-11-photo-prohibition/.

- ^ UPSHAW, William David | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives,” history.house.gov, https://history.house.gov/People/Detail/20862.

- ^ John Cooper, “Prohibition Is a Success,” accessed December 2, 2020, https://www.lcps.org/cms/lib4/VA01000195/Centricity/Domain/3996/Prohibi…

- ^ Horace Albright, “National Park Service: Origins of NPS Administration of Historic Sites (Origins),” www.nps.gov, February 1, 2001, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/albright/origins.htm.

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ “‘Man in Green Hat’ Will Be Sentenced,” The Washington Post, May 25, 1926.

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ Henry Manwell, “Opposition to the Eighteenth Amendment in the House of Representatives,” Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects, May 1, 2018, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2679/.

- ^ “18th Amendment to the Constitution - U.S. Amendment XVIII Summary,” Totally History, February 13, 2013, https://totallyhistory.com/18th-amendment-to-the-constitution/.

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday Reveals Rum Dealings in U.S. Senate Office Building”

- ^ George Cassiday, “20 to 25 Orders Daily Called Fair Capitol Trade by Cassiday”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday Reveals Rum Dealings in U.S. Senate Office Building”

- ^ George Cassiday, “Cassiday Reveals Rum Dealings in U.S. Senate Office Building”

- ^ Roger Butts, “Butts Tells How Cassiday Sold Him ‘Fifth of Gin’ at Capital,” The Washington Post, November 12, 1930.

- ^ Roger Butts, “Cassiday’s Arrest and Seizure of Black Book Bared by Butts,” The Washington Post, November 14, 1930.

- ^ Roger Butts, “Cassiday’s Arrest and Seizure of Black Book Bared by Butts”

- ^ Roger Butts, “Cassiday’s Arrest and Seizure of Black Book Bared by Butts”

- ^ “U.S. Senate: The Man in the Green Hat,” www.senate.gov, https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/The_Man_in_the_Gree….

- ^ Unpublished WETA interview

- ^ “Green Hat Man Guilty, Rum Case Jury Finds,” The Washington Post, July 16, 1930.

- ^ John Kelly, “John Kelly - John Kelly’s Washington: Congress Winks at Prohibition in Bootlegger’s Tale,” Www.Washingtonpost.Com, April 27, 2009, https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/04/26/AR2009….

- ^ “Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t,” Library of Congress

- ^ Andrew Glass, “Washington Post Profiles Bootlegger, Oct. 23, 1930,” POLITICO, October 23, 2013, https://www.politico.com/story/2013/10/washington-post-profiles-capitol….

- ^ Bart Barnes, “ROGER BUTTS DIES AT 89,” Washington Post, December 12, 1998, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1998/12/12/roger-butts-die….

- ^ George Cassiday, “Capitol Tipplers Had Weakness for Rye, Bourbon, Says Cassiday,” The Washington Post, October 28, 1930.

- ^ “Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t,” Library of Congress

- ^ “Prohibition in Washington D.C.: How Dry We Weren’t,” Library of Congress

- ^ John Kelly, “John Kelly - John Kelly’s Washington: Congress Winks at Prohibition in Bootlegger’s Tale”

- ^ Nathan Zeender, “New DC Distillery to Honor ‘Man in the Green Hat,’” mabnonline.brewingnews.com (Mid Atlantic Brewing News, 2012), http://mabnonline.brewingnews.com/publication/index.php?i=99217&m=&l=&p….

- ^ John Kelly, “John Kelly - John Kelly’s Washington: Congress Winks at Prohibition in Bootlegger’s Tale”

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)