In 1988, ACT UP Demonstrators Occupied the FDA Headquarters to Demand Action on AIDS

In the 1980s, receiving an AIDS diagnosis was devastating for many reasons. Moral and social panic had flared across the United States. One could expect to be alienated and ostracized, fired from their job or evicted from their home. Treatment was an open question. Those who had tested positive drew together, along with activists and volunteers.

One activist explained how the early backlash and response to AIDS isolated those impacted by it:

“In the absence of adequate healthcare, we have learned to become our own clinicians, researchers, lobbyists, drug smugglers, pharmacists. We have our own libraries, newspapers, drug stores, and laboratories.”1

But the most frightening aspect may have been hopelessness. There was no cure for AIDS and few drugs to fight the disease. Activist David Barr—who volunteered with the sick—recalled, “Whatever help we were providing people was really temporary… [W]e lost everybody.”2

Frustration with this hopelessness was what motivated more than 1,000 protesters to show up at the FDA headquarters in Rockville, Maryland on October 11, 1998. They were there to demand more treatments, more urgency, and more understanding. The time had come to speak up.

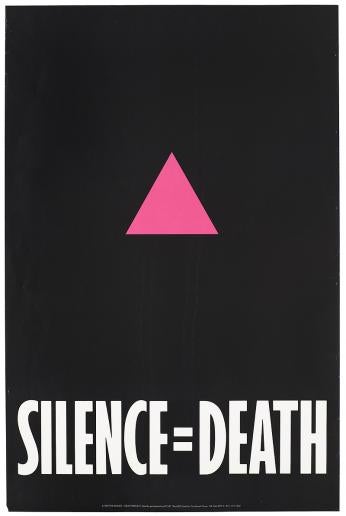

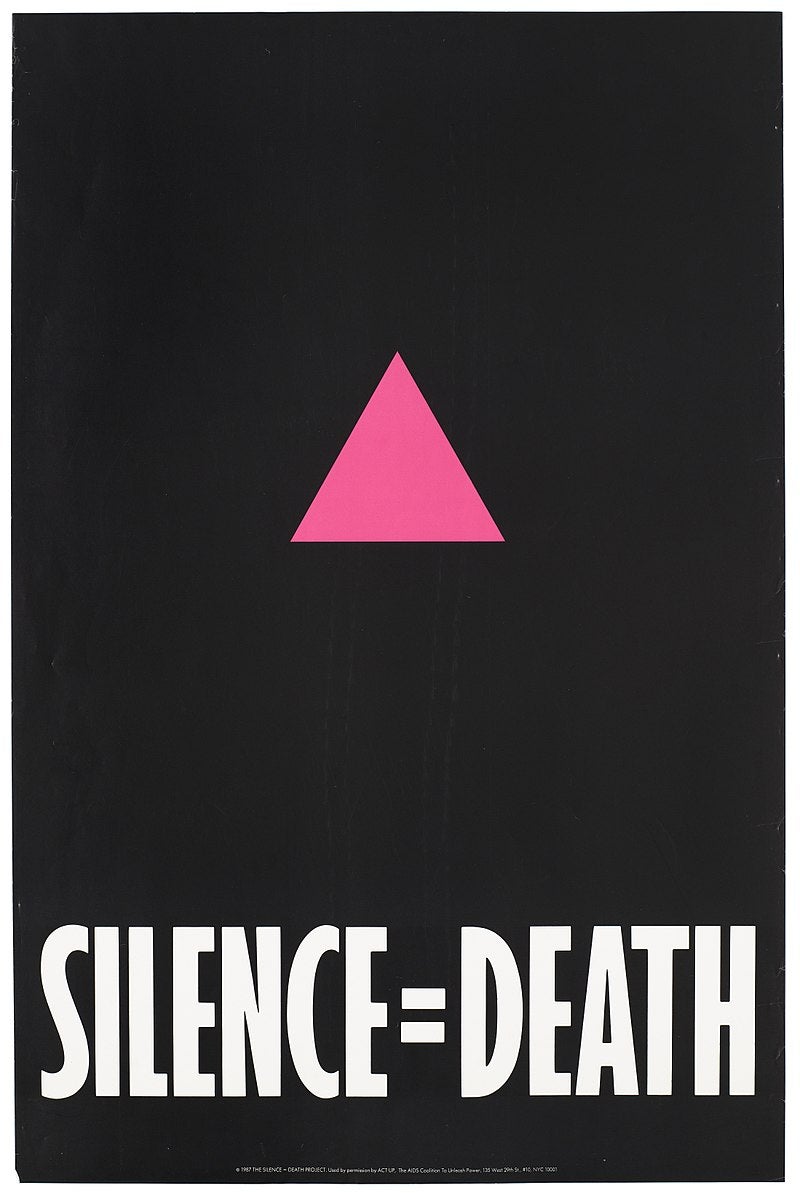

After all, as their slogan read: SILENCE = DEATH.

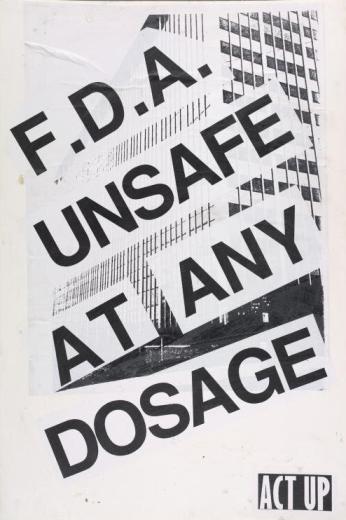

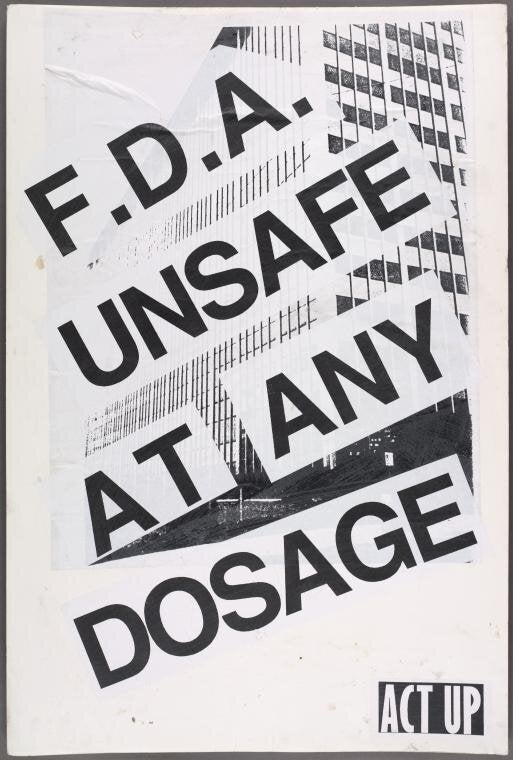

The organizer, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) had been founded a year earlier in New York City. An organization focused on political action, ACT UP immediately began agitating for more and better access to HIV drugs. “Getting drugs into bodies” was the primary goal.3 Targeting the FDA, then, was strategic: it was only “one of many… bureaucracies” to blame, but most immediately connected to their objectives.4

Tension between the FDA and activists had been growing for years. Protocols for drug approval had become more drawn-out and complicated, while public opinion was generally in favor of strict rules on who could receive investigative drugs.

Besides experimental trial drugs, AZT was the only drug approved to treat AIDS in 1988, and then only on a “compassionate use basis.”5 Notorious for brutal side effects, AZT delayed but did not prevent death. Desperate patients took to “importing” drugs available abroad in their luggage for “guerilla clinics.”6 Meanwhile, the FDA refused to release another “promising” drug because it produced blindness in some clinical tests.7

To some AIDS patients, this decision was absurd: they would gladly accept the risk of blindness if treatment might save their life.

ACT UP’s founder, Larry Kramer, railed against the FDA for not recognizing the situation’s severity. In a New York Times op-ed, he wrote, “[W]e cannot understand for the life of us… why the F.D.A. withholds [these drugs] especially when the victims are so eager to be part of the experimental process.”8

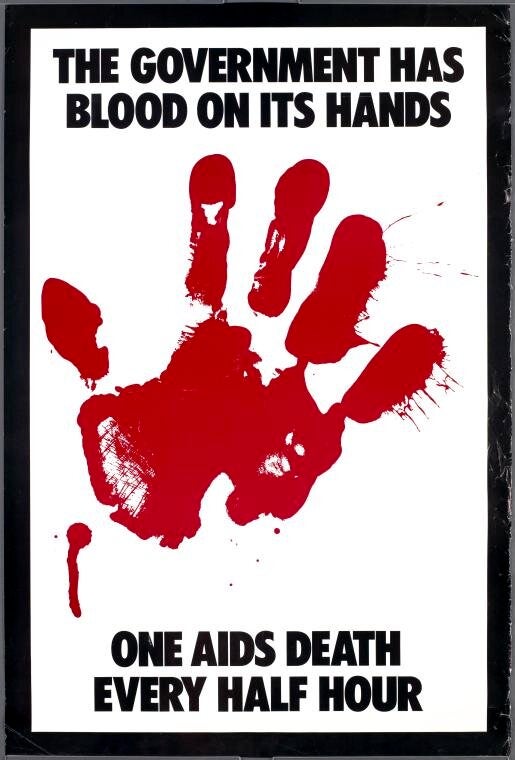

At the time, average life expectancy after an AIDS diagnosis was three years. It took ten for the FDA to approve drugs. Already, 45,000 Americans had died from the disease, and activists accused the FDA of having blood on its hands.9

ACT UP scheduled its protest just after the second exhibition of the Names Project quilt in Washington and close to the anniversary of the March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. To ensure their success, ACT UP organizers focused on two themes: publicity and knowledge.

First, they needed the eyes of the world. And so, the demonstration "was 'sold' in advance to the media almost like a Hollywood movie, with a carefully prepared and presented press kit," recalled activist Douglas Crimp in a retrospective excerpted by the The Atlantic in 2011.10 The group’s Media Committee maintained contact with press outlets and connected journalists to ACT UP members for interviews.

“This kind of activism is designed to be very telegenic. Lots of banners lots of different types of things that make good video bytes,” explained John Volger, a member of the committee. “[The mainstream media] don’t know very much, so you have to hit them again and again with simple explanations.”11

Once they had an audience, ACT UP needed to establish its credibility on all fronts. They were asking to be included in decisions; it was imperative to know what to ask for. Officially, ACT UP demanded more diverse patient groups in clinical trials, mandatory insurance coverage for experimental therapies, and a shortened approval timeline once drugs were proven safe and theoretically effective. Double-blind placebo trials should also be eradicated: it was unethical to deny medication to people with AIDS. Instead, new drugs would be tested against existing or other experimental treatments.12

In brief, ACT UP was “not asking the FDA to release drugs without safety or efficacy. We are simply asking the FDA to do it quicker.”13

Demonstrators were prepped with an FDA Action Handbook more than forty pages long explaining technical terms like INDs, relevant legislation, and drug approval pathways.14 Not only would leaders understand “every detail of the complex FDA drug approval process,” but regular picketers would be able to clearly articulate ACT UP’s complaints and proposed solutions.15

Combined with the press outreach, ACT UP had laid the foundation for, if nothing else, plenty of publicity. By October 11, “the media were not only there to get the story, they knew what that story was, and they reported it with a degree of accuracy and sympathy… unusual” for the time.16

On the morning of the 11th, more than 1,000 demonstrators approached the Parklawn Building where the FDA was headquartered. Buses and news vans surrounded the “massive, bland edifice” looking “over a neighborhood of nondescript office buildings.”17 Armed with noisemakers, signs, and fake tombstones, the crowd marched around the building, disrupting the normal silence of the parking lots. “Kitted-up riot police” looked on.18

Organizers were pleased that so many journalists had shown up, from local papers to national newsrooms. Cameras filmed the day’s speakers as they took a makeshift stage. Behind them protesters lined up, holding placards printed with their home state. When the speeches had finished, journalists were encouraged to speak to someone from their state for a local perspective.

The press “looked at us like, ‘What the hell is this,’” recalled Ann Northrop, an organizer. But “then [they] ran to that line of people.”19

Besides making their case for the cameras, the protesters also made sure the FDA employees were well aware of their presence. Raising their signs in the air, they launched into a variety of chants: “Fifty-two will die today / Seize control of the FDA!”, “Release the drugs now,” and “The whole world’s watching!”20

Through the television cameras, the whole world was watching.

The day went by noisily, but in relative peace. A few windows were smashed, and six protesters briefly entered the building. Nearly 175 protesters were arrested, some for blocking police vehicles. Most were charged only with “loitering.”21

One group staged a die-in on the steps, laying with cardboard tombstones above their heads. Their epitaphs read, RIP, Killed by FDA, I died for the sins of the FDA, and I got the placebo.22 Police stood over them while camera crews filmed.

The frustration that had inspired the demonstration was palpable. Some were selling imported or black-market drugs like dextran sulfate in protest. “You can’t get it inside [the FDA], but we’re selling it anyway!” one man called. He had taped pill packets on his poster.23

Meanwhile, FDA employees lingered in the windows to observe, some taking photos with personal cameras, flashes lighting up the glass. Demonstrators chanted up to them: “Get to work!”24

The most memorable action of the day was hoisting ACT UP’s banner over the FDA’s main entrance. From within the crowd, a young man clambered up the building’s façade and pulled a long roll of cloth from his backpack. 25 The man was Peter Staley, a 27-year-old former bond trader who had recently been diagnosed with AIDS.

“I didn’t think I was going to survive five years,” Staley said later.26 He wanted to make a statement.

He struggled to tape the fabric to the building’s exterior. ACT UP’s slogan, SILENCE = DEATH unfurled over the black banner. As they took notice, demonstrators began to cheer him on. Staley fastened the last corner, and “raised [his] arms in victory. And the place just went nuts.”27

When the demonstrators packed up to return to their homes, they did so with tired trepidation, guarding their hopes. It had taken years for the government merely to recognize the AIDS crisis. Could they really force the FDA to amend their long-entrenched and relatively popular procedures so quickly?

But astonishingly, within the week, the FDA created a new rule, effective immediately, promising faster approval drugs treating HIV-AIDS and other life-threatening illnesses.

It was good, but not enough. “We got a nickel when we needed a dollar,” said Martin Delaney of Project Inform.28 But it was a sign that the FDA was willing to include the queer community and people with AIDS in their deliberations.

In taking on the FDA’s stringent regulations, ACT UP and other AIDS organizations found allies among conservatives and libertarians. The same day he had ‘occupied’ the FDA offices, Peter Staley appeared on CNN’s debate show Crossfire. There, the show’s traditionalist conservative, Pat Buchanan, took up Staley’s side. “This is going to astonish you,” he told Staley. “But I agree with you… I think if someone’s got AIDS and someone wants to take a drug, it’s their life and if it gives him hope he oughta be able to take it.”29

Organizations like the Heritage Foundation and Cato Institute published op-eds and gave quotes in support of deregulating AIDS treatments (and other drugs). For many progressive-leaning activists, this was unusual company to keep, but as one organizer put it: “What liberal support is there?”30

Soon, AIDS activists and queer communities began to find some support within the FDA and NIH. At the time, a young Dr. Anthony Fauci headed the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which controlled the AIDS research budget. He was one of the first experts to invite activists into NIH’s decision-making processes.31

The result of these meetings became Parallel Track, a huge victory for people diagnosed with AIDS. Doctors could now prescribe experimental AIDS drugs outside of clinical trials, allowing many—especially women and minorities—to access them for the first time. Accelerated Approval, another innovation, allowed faster clearings of certain treatments. One novel drug cocktail reduced mortality by 32%.32

More good news followed: NIH’s AIDS budget tripled to over $1 billion, and anti-gay sentiment, which had peaked at 57% that year, dropped by 21 points.33 Public support for expanded access to experimental AIDS treatments rose to 79% in 1989.34 Other disease advocacy groups even began to complain “about a powerful AIDS lobby” punching above its weight.35

The crisis was far from over, but ACT UP’s ‘seizure’ of FDA forced a palpable shift in how the epidemic was framed and addressed. According to a CATO Institute retrospective published in 2020, the demonstration “shifted the blame… from the gay and trans community to a government agency that seemed to be twiddling its fingers while thousands died.”36

The protest is also remembered as a watershed moment for the AIDS crisis and even patient rights. It was the first major national action of ACT UP and marked the start of a national AIDS movement, according to historian Sarah Shulman.37

When he was interviewed in 2023, Peter Staley reflected on the moment he hoisted ACT UP’s banner over the FDA’s front doors: “Small groups of people, as long as they have a lot of determination and are highly strategic, can create change and create change pretty quickly.”

At age 63, he could look back on the protest with satisfaction. “The FDA,” he said, “caved to almost all of our demands within nine months.”38

Footnotes

- 1

How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects, 2012.

- 2

Aizenman, Nurith. “How To Demand A Medical Breakthrough: Lessons From The AIDS Fight.” NPR, February 9, 2019. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/689924838?ft=nprml&f=689924838.

- 3

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 4

How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects, 2012.

- 5

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 6

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 7

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 8

Larry Kramer, “The F.D.A.’s Callous Response to AIDS”, N.Y. TIMES, Mar. 23, 1987, at A19.

- 9

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

- 10

Crimp, Douglas. “Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988.” The Atlantic, December 6, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2011/12/before-occupy-how-aids-activists-seized-control-of-the-fda-in-1988/249302/.

- 11

ACT UP Oral History Project. “Seize Control of the FDA — ACT UP Oral History Project.” ACT UP Oral History Project. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/seize-control-of-the-fda.

- 12

Crimp, Douglas. “Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988.” The Atlantic, December 6, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2011/12/before-occupy-how-aids-activists-seized-control-of-the-fda-in-1988/249302/.

- 13

How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects, 2012.

- 14

ACT UP. “The ACT UP Historical Archive: ACT UP/New York FDA Action Handbook 9-12-88.” ACT UP Historical Archive. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://actupny.org/documents/FDAhandbook4.html.

- 15

Crimp, Douglas. “Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988.” The Atlantic, December 6, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2011/12/before-occupy-how-aids-activists-seized-control-of-the-fda-in-1988/249302/.

- 16

Crimp, Douglas. “Before Occupy: How AIDS Activists Seized Control of the FDA in 1988.” The Atlantic, December 6, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2011/12/before-occupy-how-aids-activists-seized-control-of-the-fda-in-1988/249302/.

- 17

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 18

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

- 19

Green, Eleanor. “1988 AIDS Protest at the FDA.” C-SPAN Classroom, July 10, 2019. https://www.c-span.org/classroom/document/?9730.

- 20

ACT UP Oral History Project. “Seize Control of the FDA — ACT UP Oral History Project.” ACT UP Oral History Project. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/seize-control-of-the-fda.

- 21

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 22

ACT UP Oral History Project. “Seize Control of the FDA — ACT UP Oral History Project.” ACT UP Oral History Project. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.actuporalhistory.org/actions/seize-control-of-the-fda.

- 23

How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects, 2012.

- 24

How to Survive a Plague. Sundance Selects, 2012.

- 25

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

- 26

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

- 27

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

- 28

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 29

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 30

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 31

Grossman, Lewis A. “AIDS Activists, FDA Regulation, and the Amendment of America’s Drug Constitution.” American Journal of Law & Medicine 42, no. 4 (2016): 687–742. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817701959.

- 32

Clark, Jalisa. “Challenging the Moral Authority of the FDA: A Lesson from History.” Cato Institute, November 20, 2020. https://www.cato.org/blog/challenging-moral-authority-fda-lesson-history .

- 33

Green, Eleanor. “1988 AIDS Protest at the FDA.” C-SPAN Classroom, July 10, 2019. https://www.c-span.org/classroom/document/?9730.

- 34

Clark, Jalisa. “Challenging the Moral Authority of the FDA: A Lesson from History.” Cato Institute, November 20, 2020. https://www.cato.org/blog/challenging-moral-authority-fda-lesson-history.

- 35

Green, Eleanor. “1988 AIDS Protest at the FDA.” C-SPAN Classroom, July 10, 2019. https://www.c-span.org/classroom/document/?9730.

- 36

Clark, Jalisa. “Challenging the Moral Authority of the FDA: A Lesson from History.” Cato Institute, November 20, 2020. https://www.cato.org/blog/challenging-moral-authority-fda-lesson-history.

- 37

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

- 38

Neus, Nora. “‘The Start of the National Aids Movement’: Act Up’s Defining Moment in Queer Protest History.” The Guardian, October 11, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/oct/11/act-up-hiv-aids-1988-fda-protest.

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)