Featured Topics

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)

Halloween

12 Posts

Hispanic Americans

4 Posts

Revolutionary War

8 Posts

Abraham Lincoln

22 Posts

Music History

34 Posts

National Mall

16 Posts

Women's History

52 Posts

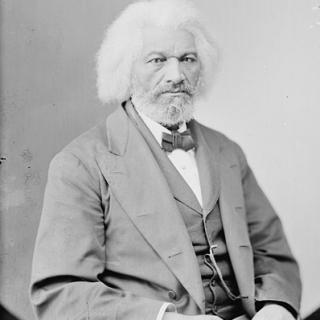

Black History

82 Posts

Love D.C. History? Support WETA!

Your donation to WETA PBS will keep making local history possible!