Featured Topics

![Sketch of the mythical fuan by Pearson Scott Foresman. [Source: Wikipedia]](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/2023-10/Goatman_Wikipedia_Faun_2_%28PSF%29.png?h=64a074ff&itok=C9Qh-PE1)

Halloween

12 Posts

Hispanic Americans

4 Posts

Revolutionary War

8 Posts

Abraham Lincoln

22 Posts

Music History

34 Posts

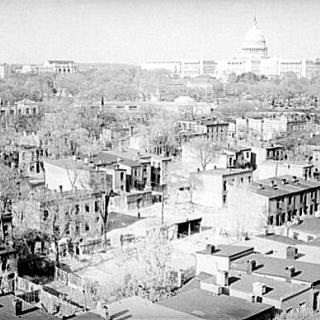

National Mall

16 Posts

Women's History

52 Posts

Black History

82 Posts

Love D.C. History? Support WETA!

Your donation to WETA PBS will keep making local history possible!

![Hundreds of draft protestors stand outside the courthouse where the trial of the Catonsville Nine takes place, peace signs up in support of the Nine. (Source: William Morgenstern, [War and draft protest], 1968. Gelatin silver print. University Archives, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UARC Photos-09-01-0025.)](/sites/default/files/styles/crop_320x320/public/street-rally-s_0.jpg?itok=E3FhlO92)